18 Chrissy Henson – Theory and Prevention Executive Report: Exploring the Criminology of School Shooters (Excerpt)

Chrissy Henson (she/her) is majoring in Psychology and minoring in Criminal Justice. She is in her Junior year at IU East, and will be graduating in the Spring Semester of 2025. Afterwards she hopes to attend law school. This paper is a sample of a semester-long project she completed for Dr. Mier’s course “Theories in Crime and Deviance.” She chose a criminal activity to research and apply popular theories of criminology. Chrissy chose the subject of school shootings and explored three different theories of criminology as a possible answer to the age-old question of “why did this happen?” Understanding criminal activity from the perspective of why can often help us develop preventative techniques, instead of being reactive to a situation. This paper also dives into data trends, victimization data, and perpetrator demographics. Professor Carrie Mier notes, “Very well-researched, presented and formatted. Great exploration of general strain theory, structured action theory, and age-graded developmental theory. Wonderful statistical and research presentation.”

Theory and Prevention Executive Report:

Exploring the Criminology of School Shooters

(Excerpt)

Introduction

The phenomenon of school shootings has become an alarming and recurrent issue in our society. This executive report is designed to help people understand school shootings by delving into crime and victimization data, state laws and penalties, and prevention techniques that may be useful to the community. Another aspect of this executive report will be to uncover the root causes of school shootings by analyzing theories from criminology to understand why shootings occur. By understanding the reasons behind school shootings, we may be able to use prevention techniques to prevent these tragedies from happening. When school shootings are mentioned three cases generally come to mind: Columbine, Sandy Hook, and Parkland.

Description and Background

School shootings are not a new phenomenon in society. There have been at least 1,204 incidents from January of 1990 to January of 2020 that resulted in at least one person being injured on a school campus in the United States. Of those incidents, schools in the United States have experienced at least 20 mass shootings over the last 30 years where four or more individuals were shot and killed (Aponte, 2022). As researchers delve into the extensive data collected over the years, they aim to uncover not only the demographic and situational patterns of these incidents but also the underlying societal factors that contribute to their occurrence. By analyzing the profiles of perpetrators, examining their motivations, and scrutinizing the availability of firearms and potential warning signs, researchers strive to provide a comprehensive understanding of the multifaceted nature of school shootings.

Crime Data – Perpetrator Demographics

Many perpetrators that commit a school shooting are males (95%) and predominantly white (approximately 61%). Most of the individuals that become school shooters report feelings of being marginalized, rejected, and are bullied. More than half of the kindergarten through twelfth grade shooters have a history of psychological problems/disorders such as depression, suicidal ideation, bipolar disorder, and psychotic episodes (Kowalski et al., 2021). It is vital to note that most individuals who have psychological conditions alone do not commit acts of mass violence.

According to the Center for Homeland Defense and Security, from 1970-2022 the vast majority of school shooters are students. Stating that 43.1% of school shooters are comprised of students, while 20.4% of shooters have no relation inside the school, and 15.3% of shooters affiliation with the specific school is unknown (Center for Homeland Defense and Security, 2023). Taken with the information from NCES, that most school shootings occur at high schools, we can deduce that most of the shooters are likely white males in the age range of 14 to 18 years old.

Crime Data – Trends

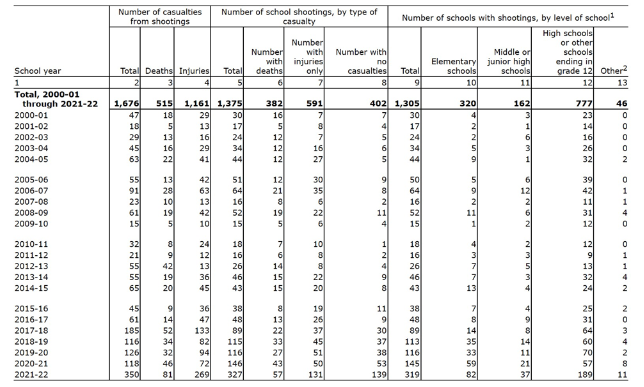

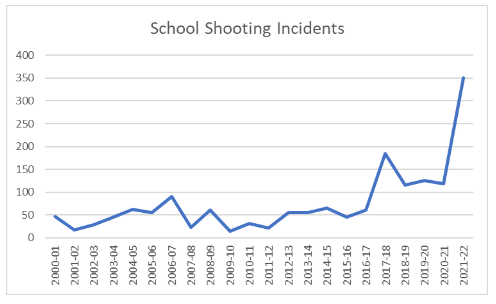

According to the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) it was reported that between ‘00/’01- ‘21/’22 school years, the United States saw a total of 1,676 school shootings that resulted in a total of 515 deaths and 1,161 injuries. A total of 1,375 different schools were affected by these incidents. The grade levels that were affected ranged from elementary schools through high schools. Since the year 2000 there have been 320 shootings at elementary schools, and 162 shootings in middle schools. High schools were predominantly affected, as there have been 777 shootings occurring in high schools in the last 20 years (NCES, 2022). Data collected by NCES is gathered during months when school is in session. Figure 1 shows a year-by-year breakdown of school shootings that have occurred from 2000 to 2022. In earlier years, there were far fewer incidents, 47. Whereas in the 2021-2022 there was a peak of 350 incidents (NCES, 2022). This data suggests that school shootings are in an upward trend. NCES suggests that the recent spike in school shootings could be linked to an increase in cyberbullying that children are experiencing outside of the classroom (NCES, 2022).

Figure 1

Note: Data set from the National Center for Educational Statistics. This data set was used to configure Figure 2. The data tracks school shootings that have occurred from the 2000 school year to the 2022 school year. (NCES, 2022)

Figure 2

Note: Figure 1: The data used in the graph was gathered from the National Center for Education Statistics (2022). Showing an upward trend in school shootings since the year 2000.

Crime Data – Victimization

Victims in school shootings can range from students to faculty within a school setting. The most common victims are the students. By looking at data gathered from the NCES report in 2022, we can see that high school students were the primary victims of school shootings. The age range of what constitutes high school varies by school jurisdiction, but commonly it is thought to be made of grades 8th-12th. Elementary school students, who are likely to be five to eleven years old, saw 320 incidents in the past 20 years. The average age range for middle school students is 11 to 14 years old, and middle schools have had 162 incidents in the past 20 years. The average age range for high school students is typically from 14 years old to 18 years old. There have been 777 school shootings in high schools over the last 20 years (NCES, 2022).

Mainstream Theory: General Strain Theory

Robert Agnew developed general strain theory as a way to explain the “why” behind deviant behavior and criminal actions. Agnew’s general strain theory posits that we experience strain throughout our lives, and the impact differs according to recency, duration, magnitude, and clustering effects (Walsh, 2020). Specific notations of general strain are that they may result in a hostile attitude towards others especially if the strain is repetitive, which would then result in an individual responding in an aggressive manner. As Palumbo states in her article “Strain and the School Shooter: A Theoretical Approach to the Offender’s Perspective,” which looks at these pent-up strains as a contributing factor to school shooters, we can start to see their motivations, rather than labeling them as random horrific acts. Through her research, Palumbo analyzed ten case studies from the years 2000 to 2013 to accurately gauge whether strain could be a factor that leads to school shootings. Factors in these cases range from a cumulative effect of continued abuse or bullying to the sudden loss of a social group, significant other, or loss of employment. In Palumbo’s 2016 study, it was found that sources of strain were in 80% of the cases, and in 60% of these, there was an inability to attain a goal (Palumbo, 2016).

Critical Theory: Structured Action Theory

The central and key concept in Messerschmidt’s structured action theory is that criminal behavior stems from gender performances. By committing criminal behavior an individual is expressing or validating their gender identity. Specifically, criminal acts would be the “answer” when an individual feels as though their masculinity or femininity is threatened (Walsh, 2020). Criminal activity is brought about in response to pressure to conform to society’s expectations of how they are meant to perform. The easiest way to explain this theory is through toxic masculinity, how men are meant to act and expected to live. Not living up to masculine ideals means straying from the societal view of patriarchy. In extreme views, it would be unmanly for a boy in school to give in to bullying, to take it without standing up for themselves. Students under that type of stress could feel as though they need to reclaim a sense of power and masculinity and that could in extreme manifestations result in a school shooting.

Within the article “Adolescent Rampage School Shootings: Responses to Failing Masculinity Performance by Already Troubled Boys,” Kathryn Farr applies the feminist theory of Structured Action Theory and doing gender to school shootings. Farr’s description of the actions taken by Klebold and Harris is that they were “injustice collectors”. This phrase can be found in a number of articles written about the Columbine Massacre. She goes on to describe how many school shootings are attributed to bullying, which can be seen as emasculating. Farr notes that boys feel a greater level of hostility towards school and have less confidence in school than girls. These are also typical characteristics of school shooters. In society, there are norms that boys are taught, such as acting tough, being cool, and the phrase that I am sure everyone has heard once or twice, “take it like a man”. These practices can lead to a toxic mindset that young males feel they must live up to. And when they fail, they are bullied, tormented, and feel like a failure to society (Farr, 2018). Without proper coping mechanisms in place, that rage can build, and in extreme circumstances, it can lead to school shootings.

Life-Course Development Theory: Sampson and Laub’s Age-Graded Theory

Key components of the age-graded theory or life-course theory as described by Sampson and Laub are social bonds, turning points, cumulative or continuation of disadvantage, and structural context. Sampson and Laub place a great emphasis on the importance of strong social bonds to family, community, and work. Attachments to others in an external fashion is a crucial part of deterring individuals from engaging in criminal activity. By having strong social bonds, an individual is likely to commit to social rules and have a higher moral compass. Turning points in an individual’s life would be moments or events that alter their life trajectory such as marriage, divorce, or employment. These moments have the capacity to change one’s life for the better, removing a reason for deviant behavior, or for the worse, adding a reason for deviant behavior. A continuation of disadvantage would be seen as disruptive or delinquent behavior in childhood that could lead to the continuation of disadvantage. Earlier behavioral problems could limit their future opportunities. Structural contextual factors emphasize the importance of human agency. Where one individual may engage in criminal behavior due to a divorce, another would not take that path (Walsh, 2020).

Theory Advocacy: Structured Action Theory

While conducting research pertinent to school shootings, one aspect stood out above all of the rest: gender difference in regard to who generally commits school shootings. Demographic patterns of individuals who commit school shootings as described by Campus Safety Magazine; school shootings that were committed by males totaled 1,838 incidents. Females accounted for 87 school shootings (Rock, 2023). This stark difference suggests that gender roles may play a significant role in violent acts. The prevalence of male offenders aligns with broader aspects of criminal behavior, particularly violent crimes where males are more frequently involved than women (Federal Bureau of Investigation, 2019). This could signal a reflective quality of social norms of expectations regarding masculinity and aggression. Studies have indicated that males who are involved in school shootings often have issues with bullying, and emasculation when they do not fully conform to masculine roles put forth by society (Steingold, 2023). These pressures placed on young men combined with other factors, such as mental illness and access to firearms, may contribute to upward trend that we are currently seeing in the rate of school shootings.

Theory Specific Prevention Techniques

Restorative properties in punishment versus solely relying on punishment as a deterrent for deviant behavior would also transform school grounds. In terms of school shootings, taking punishment into a restorative justice perspective creates a more conversational atmosphere than punitive. This form of prevention would increase the likelihood of students learning fundamental self-regulating coping strategies and emotional growth. When a child is bullied, or is the bully, this strategy aims to teach them better ways of communication and strengthens bonds, such as empathy and understanding (Elias, 2016).

Conclusion

This paper encompasses the multifaceted, complex nature of school shootings, exploring school shootings through the lens of general strain theory, life-course theory, and structured action theory. Each theory offers a unique perspective as to what could lead an individual to commit a school shooting. Preventing school shootings is not a “one size fits all” approach and would require multiple factors working together. School systems, faculty, and students would all have to work together to create a better school climate.

References

Aponte, L. (2022). Reviewing and updating the documented historical reports on school shootings: New strategies to help save lives on campuses. Education, 143(2), 74–88.

Brownlee, C. (2021, September 15). As students return to classrooms, schools hope investments in mental health will also Curb Violence. The Trace. https://www.thetrace.org/2021/09/youth-mental-health-stop-school-shootings-federal-stimulus/

Center for Homeland Defense and Security. (2023, March 2). Charts & graphs. CHDS School Shooting Safety Compendium. https://www.chds.us/sssc/charts-graphs/

Digest of Education Statistics, 2021. National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) Home Page, a part of the U.S. Department of Education. (2022). https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d21/tables/dt21_228.14.asp

Elias, M. J. (2016, November 23). Why restorative practices benefit all students. Edutopia. https://www.edutopia.org/blog/why-restorative-practices-benefit-all-students-maurice-elias

Farr, K. (2018). Adolescent rampage school shootings: Responses to failing masculinity performances by already-troubled boys. Gender Issues, 35(2), 73–97. https://doi-org.proxyeast.uits.iu.edu/10.1007/s12147-017-9203-z

Federal Bureau of Investigation. (2019, September 13). Violent crime. FBI. https://ucr.fbi.gov/crime-in-the-u.s/2019/crime-in-the-u.s.-2019/topic-pages/violent-crime

Heilman, B., & Barker, G. (2022, October 5). Masculine norms and violence: Making the connections. Equimundo. https://www.equimundo.org/resources/masculine-norms-violence-making-connections/

Kowalski, R. M., Leary, M., Hendley, T., Rubley, K., Chapman, C., Chitty, H., Carroll, H., Cook, A., Richardson, E., Robbins, C., Wells, S., Bourque, L., Oakley, R., Bednar, H., Jones, R., Tolleson, K., Fisher, K., Graham, R., Scarborough, M., … Longacre, M. (2021). K-12, college/university, and mass shootings: Similarities and differences. The Journal of Social Psychology, 161(6), 753–778. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545.2021.1900047

Palumbo, J. (2016). Strain and the school shooter: A theoretical approach to the offender’s perspective. Encompass EKU. https://encompass.eku.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1408&context=etdLinks to an external site.

Rock, A. (2023, October 17). The K-12 school shooting statistics everyone should know. Campus Safety Magazine. https://www.campussafetymagazine.com/safety/k-12-school-shooting-statistics-everyone-should-know/

Steingold, D. (2023, February 12). Study: Boys behind school shootings struggle with masculinity, taunted by peers. Study Finds. https://studyfinds.org/school-shootings-masculinity-boys/

Walsh, A. (2020). Criminology: The essentials. Sage Publications, Inc.