28 Jenifer Novak – Teaching visual rhetoric using the Harlem Renaissance in a 21st Century Classroom

Jenifer Novak is an IU East graduate English student with a concentration in rhetoric and composition. She resides in Northwest Indiana with her husband, four children, and delightfully fluffy Maine Coon. The following passage offers an edited excerpt from a seminar research project for Dr. Edwina Helton’s 682W Visual Rhetoric course. The project titled, “Teaching visual rhetoric using the Harlem Renaissance in a 21st century classroom ,” explores the use of visual rhetoric to instruct secondary English students about the history of the Harlem Renaissance. While doing so, the project aims to impart lessons in diversity and cultural literacy. Professor Edwina Helton notes, “Celebrating your exploration of theoretical approaches to visual rhetoric then applying them to your well researched project in an engaging and powerful way. It is clear you care about your teaching and students! Your well researched project will clearly lead to stronger teaching and ultimately student success!”

Teaching visual rhetoric using the Harlem Renaissance in a 21st century classroom

Student athletes post workout videos and game day wins to X to attract potential college coaches. Pop-up advertisements interrupt YouTube videos, Spotify playlists, and Hulu streaming services. Emoticons, gifs, Taylor Swift friendship bracelets, and memes flood cell phones with cultural signs and symbols. Politicians place campaign messages on billboards, bumper stickers, and door knockers. Students pin ribbons to t-shirts during Red Ribbon week, and teachers plan class trips to The Art Institute to visit the latest Picasso still life exhibit. In a multitude of contexts, teenagers engage in processing symbolic communication related to visual and verbal contexts, making the understanding of messaging embedded in visual symbols more important than ever before.

As a field of study, visual rhetoric comprises many forms. Visual rhetoric examines the intentional use of verbal and visual symbols as rhetorical acts that seek to communicate with an audience (Olsen et. al 3). In multiple forms of texts and images, visual rhetoric artifacts and products find their place within multiple interdisciplinary areas of study, such as semiotics, multimedia, communications, and cultural studies due to the “mingling of verbal and visual emphases,” (Helmers and Hill 18).

Scholar Roland Barthes describes visual rhetoric symbols in his study of semiology as a system of signs that contain a signifier and signified, forming a complex process of communication (39). A signifier acts as a physical form of a visual or textual image, while the signified embodies the conceptual meaning for the image (Barthes 39). Additionally, a third linguistic layer of meaning may accompany the signifier and signified in text. This linguistic layer allows audiences to read a text and interpret denotations, connotations, or other cultural inferences of meaning (Barthes 39).

Barthes refers to this multi-layered nature of symbols of visual rhetoric as polysemy. A textual example of polysemy would be finding a word’s denotation and connotation in the dictionary, while other social or individual interpretations form in the mind of the audience (Barthes 39). Photographs offer an example of a polysemous image in that the image introduces a potential framework of signs that can have multi-faceted sociocultural signified reference points, presenting a rich tapestry of meaning (Barthes).

With its focus on the comprehension of pictures and words, multimedia learning pairs well with the study of visual rhetoric. Multimedia scholar Richard E. Mayer defines multimedia learning theory as the “premise that learners can better understand an explanation when it is presented in words and pictures than when it is presented in words alone” (Mayer 1). Mayer asserts that enabling learners to utilize more than one mode or “channel” to send and receive information cognitive advantages (Mayer 7).

Mayer imparts that giving learners verbal materials, such as spoken or written texts, at the same time that they decode visual materials, such as illustrations, gives learners access to more than one “channel” or mode to comprehend information (Mayer 7). This is the equivalent of teaching the material twice, giving them double the amount of normal exposure to a concept (Mayer 7). Done well, this process has cognitive advantages to learners.

According to Mayer’s multimedia principle, cognitive processing improves when pictures show alongside texts to explain concepts. With the delivery of dual representations of a concept, learners actively construct dual models of material, working to understand how they are related to each other (Mayer 134). This results in deeper understanding of concepts and stronger transfer of learning to cognitive centers of the brain (Mayer 134).

In the classroom, instructors can harness student familiarity with visual rhetoric and digital technology to strengthen student learning. Multimedia provides visible support for drill-and-practice of concepts, information acquisition, and sense-making in knowledge construction (Mayer 1). Digital assessment pieces have the ability to bring classroom knowledge acquisition and practice of concepts into focus for a wide range of stakeholders. E-portfolios provide such an example of a digital platform that spotlights student learning.

As assessment pieces, e-portfolios support visible documentation of learning that can connect state standards, along with instructional goals and objectives, to e-portfolio components. For educational stakeholders, such as school administrators, teachers, and parents, e-portfolio multimodal components can function as a cumulative digital gallery of learning artifacts that display student knowledge and skills (Light et al. 51; Yancey 746). E-portfolio assignment and reflection posts give instructors an opportunity to use formative assessments to check for understanding of assignment objectives and adjust course content to aid in student understanding (Light et al. 18). Instructors also have the opportunity to take part in summative assessments by evaluating work that occurs during the course of a quarter or a semester term for a big picture assessment of learning (Light et al. 19). Essentially, e-portfolios provide students and educational stakeholders with a multimodal framework to clearly align learning artifacts to desired curriculum outcomes (Light et al. 52).

For high school English students, a study of the Harlem Renaissance provides an opportunity to blend studies in African American sociocultural history, visual rhetoric, and media studies. The following passages provide a brief history of the Great Migration and major works by Harlem Renaissance artists, a discussion of the Harlem Renaissance’s relevancy to the secondary classroom, and an example of the use of multimedia technology to teach visual rhetoric curriculum. Research on the use of visual rhetoric signs and symbols forms the basis of visual rhetoric lessons that present multimodal forms of meaning-making for students.

The Great Migration and the Harlem Renaissance

From 1910 to 1940, an unprecedented number of southern African Americans migrated to northern regions of the United States. Known as the Great Migration, this historic movement brought Black southerners to midwestern cities for several important reasons. First, these southerners sought to fill industrial job opportunities resulting from World War I (The Great Migration 1910-1970). Second, they sought a better life in the north that included an escape racially motivated violence, access to education programs, and freedom from Jim Crow laws (The Great Migration 1910-1970). These laws, active from the 1877s to the mid-1960s, comprised a set of anti-Black laws that encouraged racial discrimination and segregation of African Americans in mostly southern and some border northern states (The Great Migration 1910-1970; What Was Jim Crow-The Jim Crow Museum).

During the Great Migration, New York City began counting a plethora of talented artists and writers among its residents (The Great Migration 1910-1970). Sculptors, painters, writers, photographers, poets, and performers settled in Harlem and neighboring boroughs in droves and began to exhibit works and publish texts inspired by new political and social realities. Work created during this time captured themes of “the Black American’s African Heritage, the tradition of Black folklore, or interest in the details of Black life” (Harlem Renaissance). These themes contemplated images of Blackness that departed significantly from previous portrayals of African Americans in art (Harlem Renaissance). Embodying a spirit of newness and renewal, these works that focused on the celebration of Black cultural pride and heritage became known as the Harlem Renaissance movement or New Negro Movement (Harlem Renaissance).

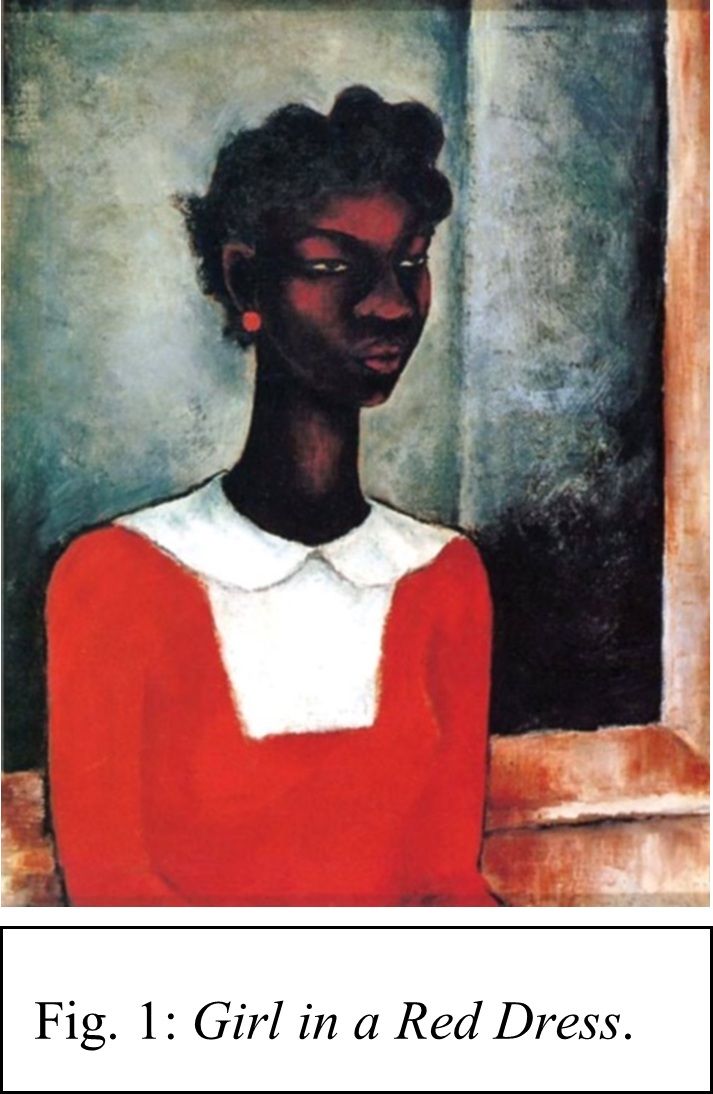

Harlem Renaissance artists sought to move past images of racial stereotypes and foolish caricatures created “under decades of peonage, servitude and stultifying tradition” in order leave behind old stereotypes and reframe Black culture (Powell 18; Thaggert 4). Photography and paintings offered two mediums through which a new positive images of African Americans flourished. In The Crisis magazine, a monthly magazine published by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, photographs depicted the rise of modern, urban African American culture with tastefully dressed Black subjects, modern businesses, and homes in urban settings (Powell 19). Harlem photographer James Van Der Zee’s photos captured “rites and ceremonies” of this urban Black population in carefully composed snapshots of school groups, weddings, funerals, parades, and church gatherings (Harlem Renaissance 35). Paintings also portrayed themes of the modern African American. Charles Alston’s Girl in a Red Dress captures an elegant, feminine “mysterious and utterly modern” Black woman (Powell 19). (See fig. 1.).

Connections between African American past and present also flowed through the use of symbols and metaphors in paintings, sculptures, and jazz music. Painter Aaron Douglas’ Aspects of Negro Life 1934 painting embodied the New Negro movement with its use of symbols and images that narrate the story of the African American from beginnings in slavery through the Great Migration (Powell 24). Three tonal panels depict a man on a wheel carrying symbols of items from the past to the present in the Great Migration (Powell 24). Further, sculptor Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller’s sculptures symbolic images presented an example of polysemous images with Ethiopia Awakening’s 1914 representation of “common African heritage” with and the depiction of the tragic lynching of pregnant Mary Turner depicted by a statue of Mary Turner holding her baby in Mary Turner (A Silent Protest Against Violence) 1919 (Harlem Renaissance 27). Finally, emotive Jazz music metaphorically recorded moody reminiscences, the excitement of city life, spiritual connections, the creativity of improvisation, and New Negro hopes and dreams of black performers (Powell 24-25). Musician Duke Ellington’s “Harlem Airshaft” uses notes that depict sights and sounds of urban life to metaphorically capture the experience of living in New York City during the Harlem Renaissance (Powell 24-25).

Throughout the Harlem Renaissance, W.E.B. Du Bois, Langston Hughes, and Alain Locke authored essays and articles encouraging artists and writers of the day to use their talents to positively influence the perception of African Americans (Thaggert). Specifically, these intellectuals concerned themselves with “how images and language work together to shape a production of racial knowledge” (Thaggert 4). These scholars concerned themselves with how descriptions of the African American body in text lead to images of racial stereotypes (Thaggert). Through editorials and essays in The Crisis magazine and other publications, these scholars encouraged other writers and artists to produce positive, modern images of Blackness (Thaggert). They understood the “form and function of the verbal in shaping images of Blackness” and its significance in freeing Black culture from old stereotypes (Thaggert 4).

Alain Locke’s The New Negro collection assisted with shaping African American writing and art (Thaggert). Locke’s work encouraged experimentation with “visual resonances in language, and the resulting images of Blackness that they created” (Thaggert 2-3). Through these creations, a complex narrative developed images of Blackness developed through visual, verbal, and mental “valuations of race” (Thaggert 3). Themes in these works mirrored themes in art reflecting a focus on African American history, creativity, and positive self-portraiture. Specifically, folk writings by “Jean Toomer, Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston and Claude McKay” drew attention to the lives of ordinary African Americans (Harlem Renaissance 25). In word and image, a conscious reconstruction of Black culture took place that reshaped images of Blackness (Thaggert 2-3).

Harlem Renaissance Relevance and Teaching

The events surrounding the tragic death of African American man George Floyd in 2020 demonstrate that the need to continue to shape positive images of African Americans remains a pressing issue in today’s society. The following lesson plans will use texts and images from Harlem Renaissance writers and artists to teach visual rhetoric to high school English students and to advance sociocultural knowledge about African American history. They encompass part of a larger quarter-long course on the use of visual rhetoric in communication.

Lesson 1: Introduction to Visual Rhetoric

Rationale: The purpose of this lesson is to instruct students about visual rhetoric so that they may recognize and use visual rhetoric in multimodal forms of communication. Visual rhetoric exists in all forms of writing including narrative, informative, and argumentative. Texts may contain visual rhetoric through the use of graphic design, figurative language, or denotation and connotation (Ehses 167-170; Bernhardt 94-106). Images also may represent signs and symbols of figurative language in the form of visual metaphors or irony (Mariani).

Goal: The overall goal of the lesson will be to assist students with identifying texts and images as modes of communication.

Objectives: To develop critical thinking skills about visual rhetoric found in media. To learn the history of the Harlem Renaissance.

Visual Rhetoric Instruction: Instructor will present a warmup about signs and symbols on a Google Slide deck. Students will fill in answers to the warmup on their Google Doc located in Google Classroom. Then, the class will discuss definitions of visual rhetoric using Google Slides. Students will then choose one video out of two videos offered to watch about visual rhetoric. Following this activity, students will complete the worksheet with one textual example of visual rhetoric and one visual example of visual rhetoric. Completed Google Docs will be submitted by students to the posted Visual Rhetoric Week One folder.

Harlem Renaissance Instruction: On their laptops with earbuds, students will read and listen to the podcast How the Great Migration Changed American History by Vermont Humanities. While listening, students will note any information that they find interesting on their Harlem Renaissance guided notes sheet. Once finished, students will open the article A New African American Identity: The Harlem Renaissance by Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture. After reading, students will record additional facts learned from this article on their guided notes sheet once more. In the last 10 minutes of class, students will share facts they learned in small groups. For homework, students will use the facts that they wrote down to create Lesson 1 Reflection for their individual Google Sites page. This reflection will answer the following three questions:

1. What is visual rhetoric? Describe two examples.

2. What was the Harlem Renaissance?

3. How do you think the Harlem Renaissance could connect to studies in visual rhetoric?

Once this half-page writing assignment is completed, students will post the link to their updated Google Sites page in the Google Classroom Assignment Folder.

In a digital world filled with multimodal texts and images, teaching students to become critical consumers of media becomes ever more important. In the classroom, studies in visual rhetoric provide learners with critical thinking skills that extend beyond traditional forms of textual analysis. Visual rhetoric embodies another form of literacy that extends beyond the confines of written language, offering students a unique set of tools to decode, interpret, and create meaning in an age of technology.

Works Cited

Alston, Charles. Girl in a Red Dress. Oil on canvas, 26 Dec. 2018, https://www.college.columbia.edu/cct/issue/winter18/article/painter-who-wouldn%E2%80%99t-be-pigeonholed.

Barthes, Roland, and Roland Barthes. Elements of Semiology. 34. [print], Hill and Wang, 1977.

Bernhardt, Stephen A. “Seeing the Text.” Visual Rhetoric in a Digital World: A Critical Source Book, edited by Carolyn Handa, Bedford /St. Martin’s, 2004, pp. 94–106.

Ehses, Hanno H. J. “Representing Macbeth: A Case Study in Visual Rhetoric.” Visual Rhetoric in a Digital World, edited by Carolyn Handa, Bedford /St. Martin’s, 2004, pp. 167–70.

Helmers, Marguerite H., and Charles A. Hill. “Introduction.” Defining Visual Rhetorics, edited by Charles A. Hill and Marguerite H. Helmers, Lawrence Erlbaum, 2004, pp. 1-23.

Light, Tracy Penny, et al. Documenting Learning with E-Portfolios: A Guide for College Instructors. 1st ed, Jossey-Bass, 2012.

Mariani, Massimo. What Images Really Tell Us: Visual Rhetoric in Graphic Design and Advertising. HOAKI BOOKS S.L, 2019.

Mayer, Richard. Multimedia Learning. 3rd ed., Cambridge University Press, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316941355.

Olson, Lester C., et al., editors. Visual Rhetoric: A Reader in Communication and American Culture. Sage, 2008.

Powell, Richard J., et al., editors. Rhapsodies in Black: Art of the Harlem Renaissance. Hayward Gallery : Institute of International Visual Arts ; University of California Press, 1997.

Thaggert, Miriam. Images of Black Modernism: Verbal and Visual Strategies of the Harlem Renaissance. University of Massachusetts Press, 2010.

“The Great Migration (1910-1970).” National Archives, 20 May 2021, https://www.archives.gov/research/african-americans/migrations/great-migration.

The Legacy of the Harlem Renaissance | The Phillips Collection. https://www.phillipscollection.org/lesson-plan/legacy-harlem-renaissance. Accessed 12 Dec. 2023.

What Was Jim Crow – Jim Crow Museum. https://jimcrowmuseum.ferris.edu/what.htm. Accessed 10 Dec. 2023.

Yancey, Kathleen Blake. “Postmodernism, Palimpsest, and Portfolios: Theoretical Issues in the Representation of Student Work.” College Composition and Communication, vol. 55, no. 4, 2004, p. 738, https://doi.org/10.2307/4140669.