48 Montana Washel – Intimate Partner Violence

Montana Washel is a sophomore majoring in Psychology and minoring in Criminal Justice. This paper is part of a research project she completed for her “Theories of Crime and Deviance” class. Professor Carrie Mier notes, “Very well-researched and presented. Great application of social learning theory, feminist criminology, and psychopathy to this topic. She had wonderful statistics, research and empathy in her writing as well as a focus on prevention.”

Intimate Partner Violence

Domestic Violence/Intimate Partner Violence

Domestic violence encompasses behaviors causing psychological, sexual, or physical harm within a household, affecting various relationships like parent-child or siblings (Walsh & Jorgensen, 2020). Intimate partner violence (IPV), a form of domestic abuse highlighted by the World Health Organization (2012), occurs in current or past romantic relationships. It includes various abuses, such as physical, emotional, coercive control, sexual, and financial abuse, aiming to gain control over a partner. IPV affects people across all backgrounds, more commonly impacting women, with about 1 in 3 women globally experiencing IPV or non-partner sexual violence.

Types of intimate partner violence, as described by Laskey et al. (2019), range from physical abuse, such as hitting or choking; emotional and psychological abuse, such as degradation and isolation; coercive control, which involves imposing strict rules; and sexual coercion. Other forms of abuse include stalking, financial manipulation, digital abuse, and spiritual or religious abuse. These behaviors form a pattern, often escalating over time. The underlying drivers of IPV are multifaceted, including individual factors like a history of childhood abuse or substance abuse, relational stressors like conflict and jealousy, and societal factors such as poverty and community violence. These drivers are interconnected and deeply embedded in social, cultural, and historical contexts.

Crime Data on Intimate Partner Violence

Quantitative data, such as crime statistics and victimization surveys, are crucial for understanding the prevalence, patterns, and dynamics of intimate partner violence (IPV). The National Incident-Based Reporting System (NIBRS), an enhanced version of the Uniform Crime Reports, offers detailed information on IPV incidents, including arrest records, the timing and location of offenses, injuries, and the use of weapons (Walsh & Jorgensen, 2020). NIBRS data, including details on victims and perpetrators, helps understand IPV’s various forms and severity. However, its reliance on reported crimes means it may not fully capture IPV’s extent, and not all law enforcement agencies use NIBRS, leading to gaps in data.

The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS) conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) collected data between September 2016 and May 2017 on the experiences of intimate partner violence from 15,152 female and 12,419 male participants (Leemis et al., 2022). The survey revealed that 47.3% of women and over 44.2% of men reported experiencing contact sexual violence, physical violence, and stalking victimization by an intimate partner at some point in their lifetime. As shown in Figure 1, 19.6% of female participants reported instances of sexual violence by an intimate partner, with 10.5% subjected to rape, 13.7% facing sexual coercion, and 8% experiencing unwanted sexual contact. Among male participants, 7.6% reported experiencing sexual violence by an intimate partner, including 2.8% who were made to penetrate, 5% who faced sexual coercion, and 2.1% who encountered unwanted sexual contact, as shown in Figure 2. These findings provide valuable insights into the patterns and characteristics of intimate partner violence.

(Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, n.d., as cited by Leemis et al., 2022)

Victimization Data on Intimate Partner Violence

Intimate partner violence can affect anyone regardless of age, gender, race, or socioeconomic status. However, certain risk factors may increase the likelihood of becoming a victim of IPV. Women are more vulnerable to experiencing IPV than men, likely due to physical differences in size and strength between males and females. Conversely, men are more likely to be the perpetrators of IPV, driven by jealousy, suspicion, or a need for control (Walsh & Jorgensen, 2020). Research shows that individuals in their late teens and early twenties are at a higher risk for intimate partner violence. Additionally, lower socioeconomic status, such as poverty and unemployment, may increase the risk of IPV.

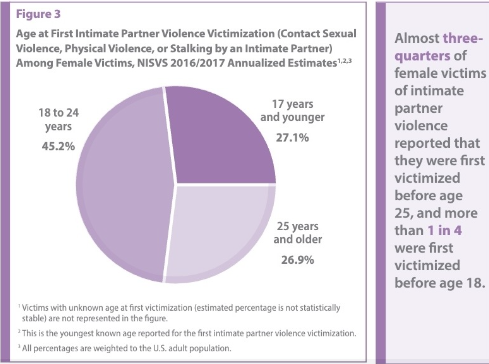

According to the National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS), with percentages weighted to the U.S. adult population, young females are more vulnerable to intimate partner violence, as data reveals that 72.3% (equivalent to 42.7 million individuals) of female victims of sexual violence, physical violence, and stalking by an intimate partner experienced their first victimization before the age of 25 (Leemis et al., 2022). New information learned from this survey data, as shown in Figure 3, is that a significant portion of female victims, approximately 27.1% or 16 million individuals, reported being first victimized by an intimate partner before age 18, illuminating the prevalence of early victimization. However, it is essential to recognize that IPV can affect individuals of all ages, and data illustrates that more than one in four female victims (26.9% or roughly 15.9 million) experienced their first victimization by an intimate partner when they were 25 years old or older.

(Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, n.d., as cited by Leemis et al., 2022)

State of Crime/Laws/Punishment Today

Intimate Partner Violence carries legal consequences designed to protect victims and hold perpetrators accountable for their actions. Several measures are in place to prevent violence, such as imposing legal punishments and sanctions. However, it is imperative to recognize that the penalties for IPV can vary significantly based on various factors, including jurisdiction, severity, and circumstances of the criminal offense (Garner et al., 2021). One of the most significant legal consequences is being arrested if law enforcement officials have evidence or probable cause to suspect IPV and can take immediate action by apprehending the alleged offender. Apprehension marks the commencement of the legal process, which could potentially culminate in initiating criminal proceedings and, if found guilty, to impose appropriate penalties. Protective orders play a critical role in safeguarding individuals from IPV. By granting restraining or protective orders, the courts can provide victims with the necessary protection to prevent further harm. Tailored provisions of protective orders may include requiring a certain physical distance between the victim and the perpetrator, prohibiting all forms of communication, and even restricting visits to specific locations. Additional penalties may involve fines, probation, and mandatory mental health treatment or intervention programs tailored to address the perpetrator’s behavior.

Furthermore, intimate partner violence victims can pursue civil remedies in addition to criminal charges. By initiating a civil lawsuit against their perpetrator, victims can seek legal recourse and compensation for the harm inflicted upon them (Lorenz et al., 2019). Such legal avenues may involve claims for medical expenses, emotional distress, pain and suffering, and other damages stemming from the traumatic experience of IPV.

Legal punishments and sanctions act as a powerful deterrent for potential perpetrators of intimate partner violence and may provide immediate relief to victims and enhance their safety. The understanding that the legal system can intervene quickly to protect victims is a potent deterrent for offenders. Laws also raise awareness about the severity of intimate partner violence and its consequences and help potential victims understand their legal rights and protections. Legal ramifications for IPV may prevent offenders from repeating their actions, as individuals held accountable for intimate partner violence may refrain from repeating similar criminal acts to avoid further legal repercussions and incarceration. Legal measures against intimate partner violence indicate the changing societal views towards this issue. They may significantly influence the cultural beliefs and values around violence within intimate relationships. However, the effectiveness of these legal consequences to successfully deter acts of intimate partner violence relies on consistency in enforcement and the availability of comprehensive support systems.

Theory #1: Social Learning Theory

As Walsh and Jorgensen (2020) described, social learning theory offers a framework for understanding the learned nature of violence in intimate relationships, emphasizing how behavior is shaped through social interactions and the principles of operant conditioning. In the context of intimate partner violence (IPV), positive outcomes following violent behavior, such as gaining control or receiving forgiveness, serve as reinforcement, increasing the likelihood of future violence. Negative reinforcement, such as violence ending an argument, also perpetuates IPV by teaching that violence is an effective solution.

This theory outlines four fundamental principles: differential reinforcement, differential association, imitation, and definitions (Walsh & Jorgensen, 2020). Differential reinforcement involves rewards or punishments after a behavior, influencing its repetition. For IPV, positive reinforcement might come from gaining control, while negative consequences could diminish the behavior. Differential association suggests learning behaviors and attitudes from social interactions; those surrounded by IPV are more likely to adopt such behaviors. Imitation involves adopting behaviors seen in others, like family or peers, and definitions refer to personal justifications or rationalizations for violence.

Researchers studied the effects of social learning theory on intimate partner violence (Cochran et al., 2016). Specifically, they investigated how different aspects of social learning theory – such as differential association, definitions, differential reinforcement, and imitation – can affect IPV. The study also aimed to determine whether an individual’s criminal propensity plays a role in moderating these effects. Unlike most social learning theory tests, which focus on general deviance, this study operationalized social learning theory components specific to intimate partner violence, allowing for a more precise examination of the theory. This study found consistent effects for differential associations and reinforcements across IPV measures, indicating that exposure to IPV-committed peers and perceived rewards for intimate partner violence are associated with higher instances of intimate partner violence (perpetration and victimization). However, definitions and imitation were less consistent predictors, with definitions only emerging as significant in one instance and the influence of imitation being weaker at higher criminal propensity levels.

Theory #2: Feminist Criminology

Feminist criminology argues that women’s criminality is affected by gender and class inequalities (Walsh & Jorgensen, 2020). Patriarchy is the central concept in all feminist theories, which is a system that privileges men at all levels of society. To fully understand gender disparities in behavior, one must consider the evolutionary logic behind them. In the context of intimate partner violence (IPV), feminist criminology links IPV to societal patriarchy, suggesting that IPV is more than individual misconduct; it is a symptom of societal issues like male dominance and female subjugation, suggesting broader societal issues rather than individual misconduct. This approach views intimate partner violence as a manifestation of power and control, primarily exerted by male perpetrators over female victims, rooted in patriarchal norms and gender inequalities. This perspective highlights how societal and cultural norms often implicitly support or excuse such violence, influencing the behavior of perpetrators. By focusing on the broader context of gender oppression and historical power imbalances, feminist criminology shifts the understanding of intimate partner violence perpetration from individual pathology to a reflection of entrenched societal issues. This approach challenges traditional views that may blame victims and instead places responsibility on the perpetrators and the societal factors that enable their behavior. The incorporation of intersectionality further deepens the understanding of intimate partner violence perpetration by considering how intersecting identities and inequalities impact violent behaviors.

The study conducted by Herzog (2007) provides a comprehensive analysis of the correlation between traditional gender-role attitudes and perceptions of intimate partner violence (IPV). This research explores a broader range of attitudes beyond overt negativity and hostility, including modern and benevolent sexism, and found that individuals with blatant, hostile sexism who align with traditional patriarchal views are more likely to downplay the severity of IPV and favor lighter punishments for perpetrators. This supports the patriarchal ideology hypothesis, which suggests that patriarchal attitudes lead to greater tolerance for violence against women. Herzog’s research shows that traditional gender-role attitudes, influenced by patriarchal ideologies, can significantly affect perceptions and tolerances of intimate partner violence.

References

Cochran, J., Jones, S., Jones, A., & Sellers, C. (2016). Does criminal propensity moderate the

effects of Social Learning Theory variables on intimate partner violence? Deviant

Behavior, 37(9), 965–976. Retrieved from https://research-ebsco-com.proxyeast.uits.iu.edu/c/k54rre/viewer/pdf/3wvdi4p2wjLinks

Garner, J. H., Maxwell, C. D., & Lee, J. (2021). The Specific Deterrent Effects of Criminal

Sanctions for Intimate Partner Violence: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Criminal Law & Criminology, 111(1), 227-271. https://proxyeast.uits.iu.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/specific-deterrent-effects-criminal-sanctions/docview/2528247570/se-2Links

Herzog, S. (2007). An empirical test of feminist theory and research: The effect of heterogeneous

gender-role attitudes on perceptions of intimate partner violence. Feminist Criminology, 2(3), 223-244. Retrieved from https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=b78196e4b4d306a9e032d2e759203b51bf477f7bLinks

Laskey, P., Bates, E. A., & Taylor, J. C. (2019). A systematic literature review of intimate

partner violence victimization: An inclusive review across gender and sexuality. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 47, 1-11. Retrieved from

Leemis, R. W., Friar, N., Khatiwada, S., Chen, M. S., Kresnow, M. J., Smith, S. G., & Basile,

- (2022). The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey: 2016/2017 Report

on Intimate Partner Violence. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved from https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/124646Links

Lorenz, K., Kirkner, A., & Ullman, S. E. (2019). A Qualitative Study of Sexual Assault

Survivors’ Post-Assault Legal System Experiences. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation: The

Official Journal of the International Society for the Study of Dissociation (ISSD), 20(3), 263–287. https://doi.org/10.1080/15299732.2019.1592643Links

Walsh, A., & Jorgensen, C. (2020). Criminology The Essentials. Fourth Edition. SAGA

Publications. Retrieved from

World Health Organization. (2012). Understanding and addressing violence against women:

Intimate partner violence (No. WHO/RHR/12.36). World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/77432/?sequence=1Links