23 Elizabeth Kanzeg – “An Era of More Favorable Conditions”: Tides of Cultural Change and Defining the Victorian Age as a Paterian Renaissance

Elizabeth Kanzeg (she/her) is a Senior from Columbus, OH majoring in English-Technical and Professional writing. She is a freelance writer and editor based in Columbus, Ohio. When she’s not poring over manuscripts and searching for misplaced commas, Elizabeth can be found reading in a cozy chair with her cats, performing onstage at her local community theatre, or antiquing with her husband. This work was prepared for Alisa Clapp-Itnyre’s English L335, who states, “Elizabeth wrote an outstanding paper on the art movements in Victorian England. It was a pure joy to read: 16 pages of analysis and two full pages of excellent excellent research! The paper really pulled together her knowledge of art in order to explore and promote Victorian era.”

“An Era of More Favorable Conditions”: Tides of Cultural Change and Defining the Victorian Age as a Paterian Renaissance

The Victorian era, a time of thunderous societal upheaval, nonetheless possesses a clearly defined identity. Indeed, Victorian culture, with all its peculiarities and singularities, influenced Western culture to so great an extent that Victorian practices and sensibilities remain steadfastly rooted today. White wedding dresses, opulent Christmas celebrations with all the trimmings, societal structures built on patriarchy and colonialism, for these practices and many more, both the superficial and the harmful, the West owes the Victorians (“connection”; “Christmas”). What, then, can be said to be the defining characteristic of Victorian culture?

In his article, “The Victorianism of Victorian Literature,” Michael Timko calls the Victorian age “a time when it was especially urgent for [man] to learn more about himself and his world” (610). He explains, “[M]any or even all ages might be characterized as being ‘engaged’” (610). What sets the Victorian era apart is the “overpowering impression […] of tremendous changes occurring” (610). He goes on, “For although all ages are ages of transition, never before had men thought of their own time as an era of change from the past to the future” (610). This unique posture sets Victorian art apart as uniquely engaged in the changing cultural tides of the era. This shared artistic disposition brings unity to an era in art history with distinct and contrasting movements. For this reason, the Victorian era could be labeled a Renaissance, as defined by Aesthetic critic Walter Pater. In the famed preface to Studies in the History of the Renaissance, Pater says, “There come, however, from time to time, eras of more favorable conditions, in which the thoughts of men draw nearer together than is their wont, and the many interests of the intellectual world combine in one complete type of general culture” (587). The Victorian general culture was defined by unprecedented societal change, as unquestioned boundaries in the areas of industry, religion, and science were challenged. In response to this, the thoughts of Victorian writers, artists, and philosophers drew together as they reacted to their changing culture as it transformed. In the early part of the era, morally concerned artists including George Cruikshank highlighted social issues like temperance. Others, like Joseph Mallord William Turner, explored natural themes in their art, responding to the Darwinian theories that were transforming the way Victorians thought about nature, the natural world, and the human condition. In the latter half of the Victorian era, the Pre-Raphaelites responded to contemporary art styles by rejecting them, returning consciously to a more Medieval approach (“Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood”). Thus, their response to societal upheaval was to recall vanishing artistic styles and religious themes, reimagining them with updated sensibilities (“Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood”). Female Pre-Raphaelite Elizabeth Siddal highlighted female experiences in her drawings and paintings, responding to the sexism she faced personally and on a societal level (Khan). Later, the artists and writers of the Aesthetic movement championed pleasure, beauty, and the pursuit of these in art and lifestyle (“Aestheticism”). This modus operandi, taken to a radical extreme by the Decadents, marks a rejection of contemporary mores (“Decadent”). This paper will dissect these artistic and literary movements and argue that the Victorian age was one of Paterian Renaissance because artists, regardless of their movement and individual philosophy, were uniquely united by their compulsion to respond to a rapidly transforming culture.

Victorians were conscious of the social issues and injustices around them (Steinbach). The Industrial Revolution brought about drastic changes in the way society worked (“Industrial”). Mass production undermined the importance of craftsmen and cities overflowed with people as factories became the primary employers of adults and children alike (“Industrial”). These societal changes reinforced class hierarchies, widening the gap between the wealthy and the poor (“Industrial”). Victorian art uniquely engages with societal issues by rebuking them outrightly. As part of his advocacy for temperance, British caricaturist George Cruikshank, concerned about the vice of alcoholism and the threat it posed to families, created a series of prints titled The Bottle (Collins).

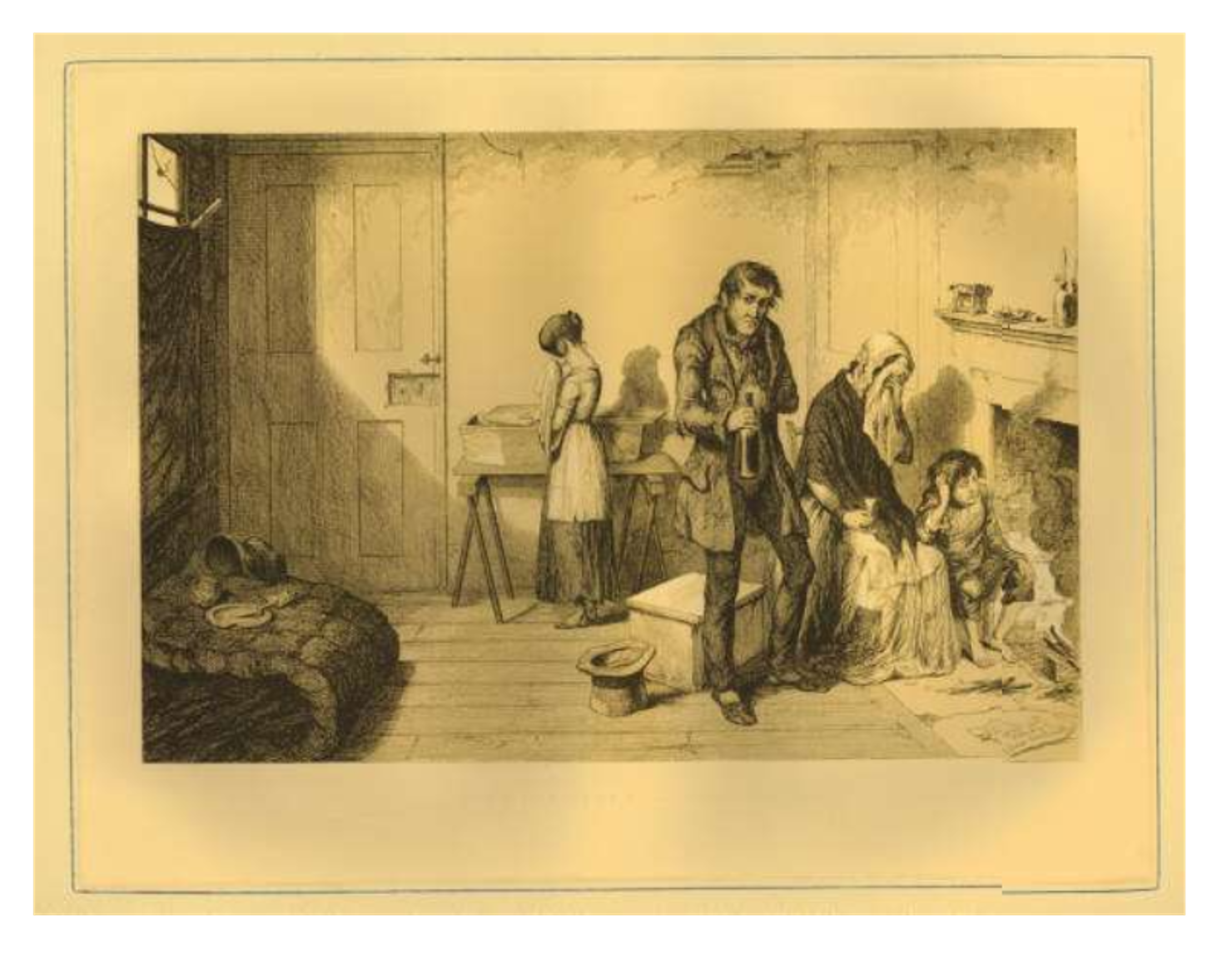

Fig. 1 George Cruikshank, The Bottle (Plate V), 1847

The etchings detail the fall of an average, fairly well-off father who begins drinking alcohol casually but quickly becomes addicted, unable to resist its power to dull his feelings (Cruikshank Plate I). He becomes a drunkard and loses his job, plunging his young family into poverty (Cruikshank Plate II). The final etchings show scenes of mourning, as the youngest member of the family dies and the father kills his wife in a fit of drunken rage (Cruikshank Plates V, IV). With its clear moral messaging, The Bottle typifies the unique Victorian approach of applying art to advocacy. Cruikshank used his art to respond to problems he identified in his own changing culture.

One of the hugest cultural influences inspiring ideological questioning and urgent philosophical repositioning among Victorians was Charles Darwin (Steinbach). His theory of natural selection revolutionized the way people thought about humanity, nature, and the universe (Steinbach). For the first time, science and religion seemed to be in disaccord. Many Victorians felt disturbed by Darwin’s claim in On The Origin of Species that the human race evolved “from the war of nature, from famine and death” (614). Facing Darwin’s evidently indisputable scientific after the idealism of the Romantic era was jarring for many. Timko explains it this way: “While the Romantics were concerned to some extent with the separation of the self and nature, there was no real sense of the epistemological despair felt by the Victorians over man’s ability to know and to integrate both” (611).

Fig. 2. Joseph Mallord William Turner, Snow Storm- Steam-Boat off a Harbour’s Mouth, 1842

In light of the questioning Darwin inspired, many Victorian artists, and writers turned to natural themes in their work, grappling with their newfound understanding of nature and natural history. Timko attributes this practice to “[t]he epistemological and Darwinian awareness of Victorians” (613). Joseph Mallord William Turner painted landscapes, often featuring violent scenes that pitted nature against man, as in Snow Storm- Steam-Boat off a Harbour’s Mouth, which shows a ship tossed upon rough waves in a violent winter storm. Turner centers the ship on the canvas, emphasizing its smallness against the vastness of the ocean. The waves appear as if they might engulf the ship at any moment (Turner). By engaging with the dangerous elements of nature, Turner responded to revolutionary Darwinian ideology which suggested inherent violence in the natural world.

Writer Thomas Hardy invoked the pastoral tradition in his novels, setting his narratives against the idyllic backdrop of the English countryside. But rather than idealizing life “[f]ar from the madding crowd’s ignoble strife,” Hardy subverts pastoral themes and traditional literary devices, bringing ironic layers of meaning and context to his works (Gray line 73). As Owen Schur explains in his book Victorian Pastoral: Tennyson, Hardy, and the Subversion of Forms, “The more we read Hardian pastoral, the more we see that Hardy’s irony is as much about the subversion and renewal of the rhetoric of tradition, as it is about the thematic incidents he represents by means of this rhetoric” (158). For example, Hardy sets his novel Far From the Madding Crowd in a beautiful rustic English village. It’s against this landscape that the tumultuous, dramatic, often violent lives of his characters unfold. This creative decision allows Hardy to explore the relation between the natural and the human and ironically accentuate and subvert the pastoral. Hardy undermines the idyllic pastoral view of rural life in England at a time when industrialization threatened the existence of this lifestyle (“Industrial”). Largescale operations replaced self-sufficient family farms, urban populations grew at a rapid rate as the need for factory workers increased, and industrial runoff and fumes polluted Britain’s skies and waterways (“Industrial”). Hardy’s purposeful irony emphasizes the dissonance between rural and urban life in the Victorian era. He uses his writing to react to rapid societal changes in his day, specifically the rapid vanishing of pastoral life.

The Pre-Raphaelite movement advocated a return to artistic sensibilities popular before the high Renaissance and painters like Raphael (“Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood”). The subjects of their paintings, often drawn from mythology, literature, myth, or scripture, are placed against lush backgrounds of natural beauty (“Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood”). In an age of mechanization when industrialization led to blight, pollution, and urbanization, pure natural themes appealed, pressingly, to this group. Timko explains that “[t]he Victorians were the first to face the problem of defining man’s humanness” because of “the question of [man’s] ability to know for certain anything about himself, his world, or his God” (615). The movement’s focus on mystic, mythological, and spiritual themes also demonstrates their interest in using religious aesthetics, themes, and symbols for more earthly artistic applications (McKiernan 295).

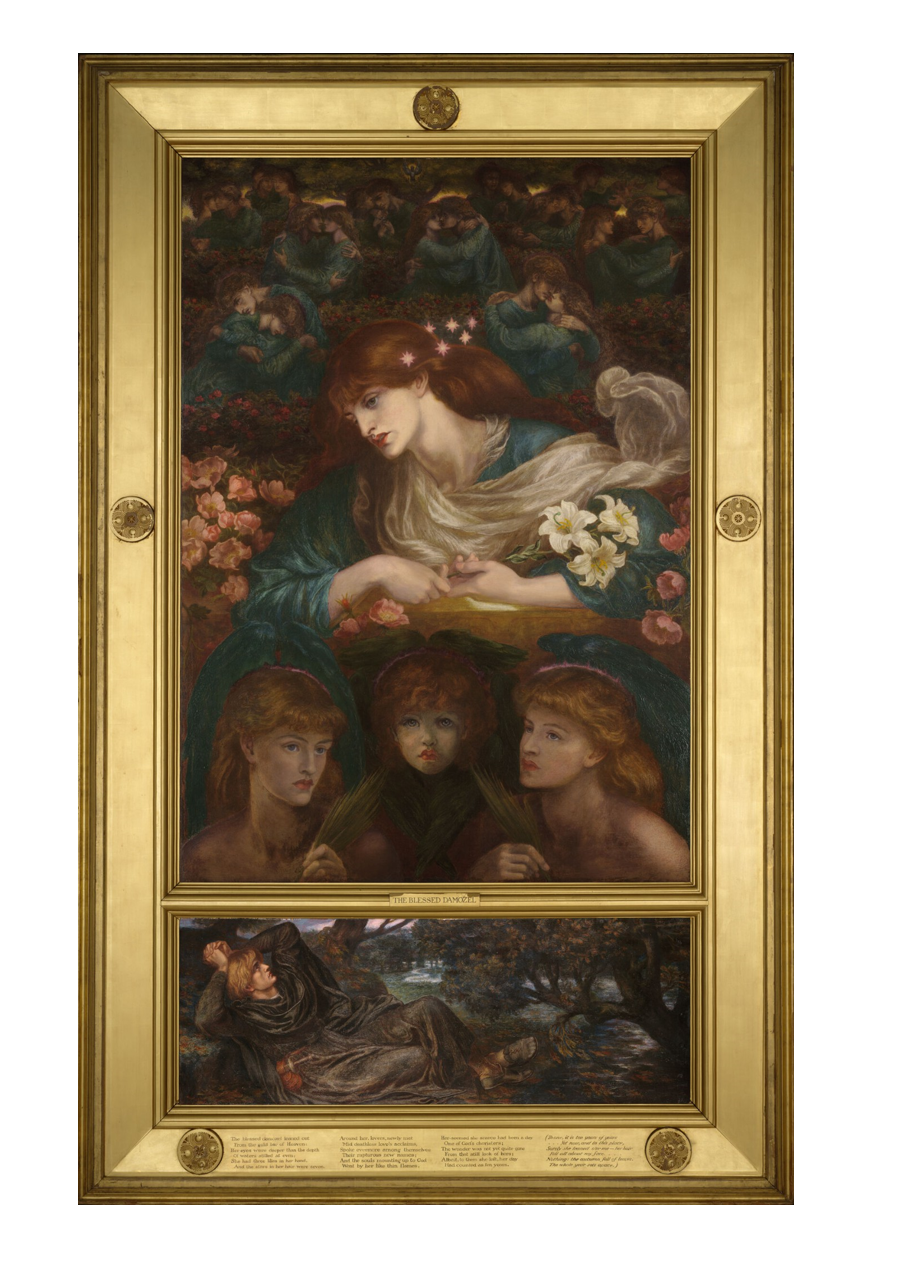

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, who founded the Pre-Raphaelite movement alongside Sir John Everett Millais and William Holman Hunt, was a distinguished poet as well as painter, often painting paintings to illustrate his writing (“Brotherhood”). His poem and accompanying painting by the same name, The Blessed Damozel, typifies Pre-Raphaelite conventions (“Dante Gabriel Rossetti” 518). The poem describes the sad lament of a beautiful woman who has died and entered heaven, leaving her lover behind on earth. Though the Damozel is surrounded by paradisical scenery and angelic company, her thoughts and gaze are cast downwards as “she bow’d herself, and stoop’d” (Rossetti line 49). Rossetti steeps the poem and accompanying painting in rich symbolism, borrowing from Catholic iconography. He mentions “the Dove,” representing the Holy Spirit, and uses symbolic flowers including the “white rose of Mary’s gift” to reference the Virgin Mary (Rossetti line 87; Greenblatt, 520n5; Rossetti line 5).

Fig. 3. Dante Gabriel Rossetti, The Blessed Damozel, 1871

As the poem continues, the Damozel’s lover interjects, his words woven into the lines using parentheticals. He responds to her hopelessness with resignation. The Damozel prays incessantly for reunification, but to no avail. The charms of heaven hold no comfort for her. She cries, “‘Have I not prayed in heaven?— on earth; / Lord, Lord, has he not prayed? / Are not two prayers a perfect strength? / And shall I feel afraid?’” (lines 69-72). Why does Rossetti imply the Damozel’s discontentment with her place in “the golden bar of heaven” that she, for her blessed and pure nature, has earned (line 1)? “The Blessed Damozel” can be read as Rossetti’s response to secularization resulting from the widespread religious doubt of his time. Rossetti was pleased to operate artistically in traditional Christian and Catholic frameworks, employing or subverting religious symbolism and borrowing from Medieval iconography at will (Bryson). But, for all its heavenly symbols and allusions, The Blessed Damozel is pointedly earth-focused. Rossetti positions heaven as an obstacle between the Damozel and her lover, rather than a holy reward or painless paradise.

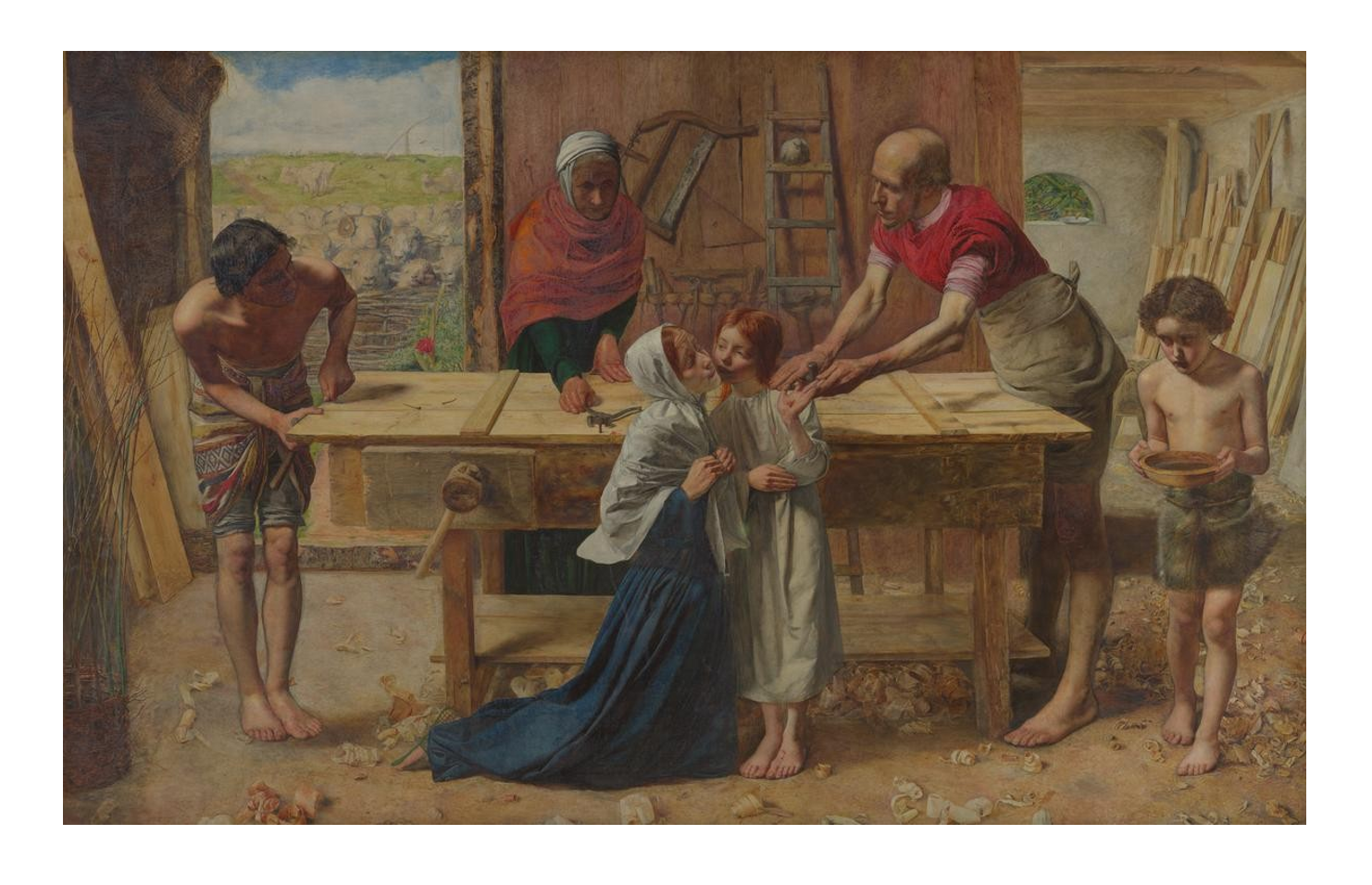

Fig. 4. Sir John Everett Millais, Christ in the House of His Parents, 1849-1850

In his painting Christ in the House of His Parents, Pre-Raphaelite Sir John Everett Millais similarly favors the earthly over the spiritual, portraying Christ as a young red-haired boy and Mary and Joseph as everyday working people (McKiernan 294). The painting was not received well and upset many Victorian sensibilities (McKiernan 295). Many viewers found the more modern representation of the holy family distasteful and the setting too meager and irreverent (McKiernan 295). Upon seeing the painting for himself, an aghast Charles Dickens exclaimed that the Christ child looked like “a hideous, wry-necked, blubbering, red-haired boy in a night-gown” (qtd. in McKiernan 295). But Millais’ artistic choices are purposeful. He incorporates symbolism into Christ in the House of His Parents. The young Christ child has injured his hand, the wounds mirroring those he will suffer years later on the cross (McKiernan 294). A dove sits above the figures, representing the Holy Spirit, while the sheep outside reference the laity (McKiernan 294). Thus, like Rossetti, Millais co-opts religious symbolism and themes, placing them in earthly contexts. The Pre-Raphaelites saw religion as something aesthetically and thematically beautiful to draw from, but perhaps nothing more. In this way, their art acts as a response to secularization, the prevalent religious disengagement of Victorian culture.

Fig. 5. Elizabeth Eleanor Siddal, Sir Patrick Spens, 1856

Elizabeth Siddal, known widely as Lizzie Siddal, was a Pre-Raphaelite poet and artist (Blumberg). She married Dante Gabriel Rossetti in 1860, though she had been his muse and model for several years prior (Blumberg). Tragically, the merit and impact of her art are often diminished and she’s remembered best for her tragic death via laudanum overdose (Bradley 141). But Siddal’s beautifully composed drawings and paintings display great artistry and have recently received more recognition as her influence on Rossetti and other Pre-Raphaelites is taken more seriously (Khan). Siddal often employs realism in her paintings and drawings (Khan). In contrast to the work of her male Pre-Raphaelite counterparts, Siddal’s compositions are often more intimate, her colors more muted, and her scenes more tender (Khan). In Sir Patrick Spens, Siddal’s painting based on the ancient Scottish ballad of the same name, Siddal captures the hopelessness and grief of a small group of women waiting in vain for their husbands to return from sea (Tate). The women cluster together, comforting their children as they gaze desperately toward the horizon for any sign of a ship. Siddal shows the strength of the women as they face the tragic reality of their husbands’ demise. They wait with forbearance, even as hope dwindles. She also highlights their motherly tenderness. The women embrace their children holding them in their arms or gently cradling their small hands. Siddal’s figures are lifelike. Their poses are remarkably familiar and realistic. Siddal’s artistic strengths are on full display in Sir Patrick Spens. Her sincere portrayal of this intimate moment highlights where her distinct style and choice of subject matter divulge from that of other Pre-Raphaelites. In an era and artistic movement marked by sexism and female exclusion, Siddal painted realistic and tender portrayals of overtly female experiences.

Taking inspiration from Pre-Raphaelites like Rossetti and to some extent Siddal, aestheticism borrowed from the movement, extracting and focusing on their ideal of ars gratia artis and the preeminence of beauty (“Aestheticism”). Aesthetes applied these ideas not only to their art but to their lifestyles (“Aestheticism”). In Studies in the History of the Renaissance, critic Walter Pater expresses the key tenets of Aestheticism, saying, “The aesthetic critic, then, regards all the objects with which he has to do, all works of art, and the fairer forms of nature and human life, as powers or forces producing pleasurable sensations” (585). For the Aesthetes, beauty in art and life becomes an end to itself to be cultivated through pleasure-seeking.

It is these ideas that Aesthetic writer Oscar Wilde explores in the dark novel The Picture of Dorian Gray. This novel, which details the corruption and subsequent self-inflicted fall of a decadent young man, may reflect Wilde’s own wrestling with his conflicted sense of identity. In his article “Aestheticism, Homoeroticism, and Christian Guilt in The Picture of Dorian Gray,” Joseph Carroll posits that “[t]he three chief male figures in the novel all embody aspects of Wilde’s own identity, and that identity is fundamentally divided against itself” (290). Wilde himself claimed that “Basil Hallward is what I think I am; Lord Henry, what the world thinks of me: Dorian what I would like to be–in other ages perhaps” (qtd in Carroll 290). Carroll suggests that Wilde wrestles with guilt and identity in The Picture of Dorian Gray in the context of Victorian culture. The novel, Carroll explains, comes at a time when Wilde’s homosexuality contradicted prevailing cultural standards and Darwinian scientific findings that added biological context to human sexuality. Wilde’s strange novel, then, serves as his response to the shifting grounds of Victorian culture which threatened elements of his identity, causing him, Carroll claims, to feel guilt evidenced by the cautionary tone of the story. Explorations of guilt permeate the book. In chapter eight, as Dorian Gray simmers in a fit of ill-tempered reflection after being disappointed by Sybil’s acting performance, Wilde notes, “When we blame ourselves, we feel that no one else has a right to blame us. It is the confession, not the priest, that gives us absolution” (81). Thus, Wilde exemplifies the Victorian artistic quality of response to change, or, engagement with culture.

Victorian artists responded directly to an era characterized by change through their art. Regardless of movement or creed, Victorian artists are unified by this engagement with the unique and rapidly evolving culture of their time. Artists like Cruikshank responded to moral issues they saw in society, hoping to inspire change. Turner and those interested in the natural world engaged the worldview-shifting findings of Darwin, exploring the inherent violence of nature and man’s place in the universe. Pre-Raphaelites wrestled with Victorian religion, divorcing it from faith in order to engage with its aesthetics while placing importance on the earthly rather than the heavenly. Elizabeth Siddal honored female experiences in her art, responding to the sexist attitudes she faced personally and culturally. The Aesthetes placed beauty and its pursuit as their central tenet. In The Picture of Dorian Gray, Wilde wrestles with his personal identity in the context of Victorian societal standards. His art responds directly to his culture, a proclivity shared by a diversity of Victorian artists. It is this unity of mission and alignment of method that qualifies the Victorian era as a Paterian Renaissance. Pater describes a “general spirit and character” which will distinguish an age (586). For the Victorians, this spirit was the tides of cultural change that unsettled, provoked, and inspired them.

Works Cited

“Aestheticism: Oscar Wilde, Decadence & Symbolism.” Britannica, 12 March 2024, https://www.britannica.com/art/Aestheticism.

Blumberg, Naomi. “9 Muses Who Were Artists.” Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/list/9-muses-who-were-artists. Accessed 29 April 2024.

Bradley, Laurel. “Elizabeth Siddal: Drawn into the Pre-Raphaelite Circle.” Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies, vol. 18, no. 2, 1992, pp. 137-187. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/4101558.

Bryson, John and William Gaunt. “Dante Gabriel Rossetti – Pre-Raphaelite, Poetry, Art.” Britannica, 15 April 2024, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Dante-Gabriel-Rossetti/Poetry.

Carroll, Joseph. “Aestheticism, Homoeroticism, and Christian Guilt in The Picture of Dorian Gray.” Philosophy and Literature, vol. 29, no. 2, 2005, pp. 286-304, https://doi.org/10.1353/phl.2005.0018.

Collins, Philip. “George Cruikshank: Victorian era, caricaturist, illustrator.” Britannica, 26 February 2024, https://www.britannica.com/biography/George-Cruikshank.

Cruikshank, George. The Bottle. 1847, The British Museum, https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1865-1111-2309-2316.

“Dante Gabriel Rossetti.” The Norton Anthology of English Literature, Volume E, 10th edition, edited by Stephen Greenblatt, et al., W.W. Norton, 2018, pp. 517-518.

Darwin, Charles. “The Origin of Species.” The Norton Anthology of English Literature, Volume E, 10th edition, edited by Stephen Greenblatt, et al., W.W. Norton, 2018, pp. 606-614.

“Decadent: Romanticism, Symbolism, Aestheticism.” Britannica, 10 April 2024, https://www.britannica.com/event/Decadent.

Gray, Thomas. “Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard.” Poetry Foundation, 1751, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/44299/elegy-written-in-a-country-churchyard.

Greenblatt, Stephen et. al, editors. The Norton Anthology of English Literature, Volume E, 10th edition, W.W. Norton, 2018.

“Industrial Revolution: Definition, History, Dates, Summary, & Facts.” Britannica, 19 April 2024, https://www.britannica.com/event/Industrial-Revolution.

Khan, Amina. “Elizabeth Siddal in Her Eyes.” The Art Institute of Chicago, 7 December 2023, https://www.artic.edu/articles/1093/elizabeth-siddal-in-her-eyes.

McKiernan, Mike. “Sir John Everett Millais Christ in the House of His Parents (The Carpenter’s Shop).” Occupational Medicine, vol. 59, no. 5, 2009, pp. 294–295. Oxford Academic, https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqp071.

Millais, Sir John Everett. Christ in the House of His Parents. 1849-1850, Tate, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/millais-christ-in-the-house-of-his-parents-the-carpen ters-shop-n03584.

Pater, Walter. “Studies in the History of the Rennaisance.” The Norton Anthology of English Literature, Volume E, 10th edition, edited by Stephen Greenblatt, et al., W.W. Norton, 2018, pp. 584-589.

“Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood: 19th Century British Art Movement.” Britannica, 4 April 2024, https://www.britannica.com/art/Pre-Raphaelite-Brotherhood.

Rossetti, Dante Gabriel. The Blessed Damozel. 1871, Harvard Art Museums, https://harvardartmuseums.org/collections/object/299805.

Rossetti, Dante Gabriel. “The Blessed Damozel.” The Norton Anthology of English Literature, Volume E, 10th edition, edited by Stephen Greenblatt, et al., W.W. Norton, 2018, pp. 518-522.

“Rossettis, The: Radical Romantics Exhibition Guide.” Tate, April 2023, https://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-britain/the-rossettis/exhibition-guide.

Siddal, Elizabeth Eleanor. Sir Patrick Spens. 1856, Tate, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/siddal-sir-patrick-spens-n03471.

Steinbach, Susie. “Victorian era: History, Society, & Culture.” Britannica, 23 February 2024, https://www.britannica.com/event/Victorian-era.

Schur, Owen. Victorian Pastoral: Tennyson, Hardy, and the Subversion of Forms. Ohio State University Press, 1989.

Tate. “Caption For ‘Sir Patrick Spens,’ Elizabeth Eleanor Siddal, 1856.” Tate, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/siddal-sir-patrick-spens-n03471. Accessed 29 April 2024.

Timko, Michael. “The Victorianism of Victorian Literature.” New Literary History, vol. 6, no. 3, 1975, pp. 607-627. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/468468.

Turner, Joseph Mallord William. Snow Storm – Steam-Boat off a Harbour’s Mouth. 1842, Tate, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/turner-snow-storm-steam-boat-off-a-harbours-mouth-n00530.

“Victoria connection, The.” Victoria and Albert Museum, https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/the-victoria-connection. Accessed 21 April 2024.

“Victorian Christmas.” Royal Museums Greenwich, https://www.rmg.co.uk/stories/topics/victorian-christmas. Accessed 21 April 2024.

Wilde, Oscar. The Picture of Dorian Gray: Authoritative Texts, Backgrounds, Reviews and Reactions, Criticism. 3rd edition, edited by Michael Patrick Gillespie, W.W. Norton, 2020.

Works Consulted

“Rossettis, The: Radical Romantics Exhibition Guide.” Tate, April 2023, https://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-britain/the-rossettis/exhibition-guide.

Media Attributions

- Kanzeg pic 1

- Kanzeg pic 2

- Kanzeg pic 3

- Kanzeg pic 4

- Kanzeg pic 5