26 [Reading] T04-L08-A3: Long Distance Trade

“Long-distance trade and economy before and during the age of empires”

Altaweel, M. and A.Squitieri. 2018. “Long-distance trade and economy before and during the age of empires.” In Revolutionizing a World: From Small States to Universalism in the Pre-Islamic Near East, 160-178. UCLA Press. [DOI]

NOTES ON THIS TEXT

I have modified all dates in this article to follow the conventions used in this class.

If you need a more general English dictionary to look up unfamiliar vocabulary, I recommend Merriam-Webster Online.

This chapter explores how long-distance trade was affected during the AoE. Similarly to earlier chapters, this is done by comparing patterns before and during the AoE. We use trade patterns based on the distribution of specific trade goods for different periods. The key result demonstrated is how trade networks enlarged under the AoE to an extent that was less possible during the Bronze and Early Iron Ages, as empires enabled easier access to goods and facilitated faster movement over longer distances. Thus, as a result of large-scale empires, the movement of people to cities increased and long-distance trade itself began to transform as the movement of goods became easier.

6.1 Long-distance trade in the pre-AoE

Both textual and archaeological evidence indicate that long-distance trade networks were a fundamental component of pre-AoE economies in the Near East. Various communities and city-states of Central Asia, the Indus Valley, Iran, South Arabia, Mesopotamia, the Levant and the Eastern Mediterranean were interconnected in the exchange of both finished objects and raw materials (T. C. Wilkinson 2014). In most cases, finished objects included highly prized items, such as beads, amulets and stone vessels, used by wealthy individuals and elites who boasted of their status in funerary or royal contexts; precious metals such as gold also travelled long distances to meet the demand of the Near Eastern elite. More utilitarian metals, such as copper and tin, were exchanged across a wide area and were essential for the development of bronze items (Figure 6.1). Bronze Age long-distance trade also permitted the development of skilled craftsmanship, which facilitated the production of finished items, as witnessed by several artisanal quarters established in cities across the Near East (Steel 2013: 157–90).

- Figure 6.1 Map showing the main sites and regions involved in Bronze Age long-distance trade, and the materials exchanged, in their regions of origin

In the 3rd millennium BCE [BC], semi-precious stones were among the most common items traded across long distances. These were lapis, carnelian, chlorite and steatite, whose geological sources were located in an area encompassing Afghanistan, eastern Iran and the Indus Valley (Moorey 1994: 77–103). These stones were traded as raw materials or were used to make beads, seals, amulets and small vessels which were distributed across Central Asia, Iran, Mesopotamia, the Levant, Egypt and, more sporadically, the Balkans (T. C. Wilkinson 2014: 125–37, 262–3, 282–3). In many cases, such objects were buried in royal tombs, the best example being the Royal Cemetery of Ur (Woolley 1934). Various commercial routes connected distant areas, some over- land across Iran, and others via the Persian Gulf, which connected Arabia and the Indus region (Tosi 1974); as is often the case, trade contacts also entailed the transmission of ideas on styles. The spread of the so-called intercultural style chlorite vessels from Central Asia to Mesopotamia and the Gulf (Amiet 1986) is a good example of such a transmission of design ideas (Figure 6.2). Another example comes from double spiral-headed pins (Huot 2009), which are possible indicators of similar clothing styles spreading from Central Asia to Anatolia and the Balkans during the 2nd millennium BCE [BC] and indicating that large trade networks had spanned these regions.

- Figure 6.2 Chlorite vessel of the so-called intercultural style showing a musical procession. Found at Bismaya (ancient Adab, Southern Mesopotamia) and dating to the Early Dynastic period (2700–2500 BCE; Oriental Institute Museum, University of Chicago; Daderot 2014)

The Arabian Peninsula was included in this long-distance trade network, copper being particularly prized. According to Sumerian texts from the 3rd millennium BCE [BC], copper was sourced from Magan (corresponding to modern Oman), but in the early 2nd millennium BCE [BC] other sources located in Northern Mesopotamia and Anatolia began to be exploited, and continued to be so at least until the 18th c BCE [BC], when Cyprus became the main source of this metal for most of the Near East (Moorey 1994: 245–6). Copper was essential to meet the high demand of Mesopotamian and Syrian palaces for the production of bronze tools and weapons (Weeks 2004). In the early 2nd millennium BCE [BC], textual evidence from Kültepe (ancient Kanesh) in Central Anatolia informs us about donkey caravans departing from Ashur in Northern Mesopotamia, loaded with textiles from Babylon and tin (probably from Iran), that eventually reached Kanesh, where these products were exchanged for silver and gold (Veenhof 1969; Larsen 2015). Another important source of information about Bronze Age long-distance trade is the 14th c BCE [BC] archive of Amarna, Egypt, whose tablets, written in Akkadian, cast light on an intricate gift-exchange network involving Egypt, the Aegean, the Levant and Mesopotamia, where precious metals and various objects bestowed with high value were exchanged (Cochavi-Rainey and Lilyquist 1999). Another product traded across long distances was amber, which was sourced in the Baltic area and reached the Levant through the Aegean, as witnessed by small amber objects found at Thebes in Tutankhamun’s tomb and in the Royal Tomb of Qatna (Syria) in the 14th c BCE [BC] (Mukherjee, Roßberger, James et al. 2008). On the other hand, from what is observable so far, amber does not appear to reach areas east of the Levant, that is, Mesopotamia and Central Asia. Finally, relics found off the Eastern Mediterranean coast, for example near Uluburun and Cape Gelidonya, yielded a high quantity of ceramics, metal ingots and other luxury objects which were exchanged among different political entities of the Levant and the Eastern Mediterranean (Bass 1967; Pulak 1998).

The Bronze Age long-distance network encompassed an area stretching from Central Asia to the Eastern Mediterranean, including the Indus Valley and South Arabia, but beyond these limits trade for items was far more sporadic, and few items are found outside these areas. It is difficult to say how such a network was controlled or functioned, although it probably consisted of a set of overlapping trade routes that various parties organically developed, maintained and participated in because they had some stake in or benefit from the trade. Royal palaces and temples appear to have had a fundamental role in long-distance trade, in that they organized expeditions of emissaries or traders to foreign lands, thus framing the trade into political and diplomatic relations (Lipiński 1979). However, such evidence might be biased, since the archives of palaces and temples are the major sources of recorded information known to us and represent a limited view. The written evidence from Kanesh, on the contrary, indicates the existence of business and trade controlled by private families, with state intervention limited to the collection of taxes and participation through private families (Michel 2001). If we can assume that the Kanesh trade network was a typical example of long-distance trade in the Bronze Age, then such trade appears to have been a composite of both public and private spheres working together or independently. The Kanesh archive also informs us of the existence of an enclave of Assyrian merchants living in this city and managing their businesses there (Larsen 2015); it is possible that this was not an isolated case in the Bronze Age and that other communities of merchants lived far from their place of origin. One example comes from Late Bronze Age Ugarit, where tablets inform us of merchants from the Levantine coast, namely from Arwad, Byblos, Beirut, Tyre, Akko and Ashdod, who were stationed in Ugarit to run their businesses (Wachsmann 2009: 40).

It is noteworthy that the Bronze Age long-distance trade net- work depended heavily on the changing political landscape. In many instances, political turmoil, dynastic squabbles, conquests and population movements affecting one end of the network caused much of the trade system to break down or be disrupted. For example, at the end of the 3rd – beginning of the 2nd millennium BCE [BC], trade connections between Mesopotamia, Central Asia and the Gulf appear to be drastically reduced; the causes of this phenomenon seem to vary, but the collapse of the complex societies in the Indus may have played a role (Moorey 1994: 245–6). The Hittite conquests of the late 18th c BCE [BC] possibly brought about the end of the Kanesh– Ashur trade system; the arrival of the Sea Peoples on the Levantine coasts at the start of the Iron Age (about 1200 BCE [BC]) coupled with the weakening and disruption of most Levantine palace economies caused the end of the Late Bronze Age political and long-distance trade system (Yasur-Landau 2010: 102; Van De Mieroop 2016). It seems that the Bronze Age long-distance and intercultural trade was far-reaching, but it was also heavily affected by political changes that occurred cyclically in the pre-AoE. Though this observation may be biased by the nature of our sources, which are often sporadic, the breakdown of long-distance trade suggests that these systems were fragile, and that political frag- mentation could affect the trade networks that were active in the Bronze Age. What this demonstrates is that trade systems were dependent, to a great extent, on larger political systems. When political systems were relatively stable, as they were in periods of the Late Bronze Age, we see trade thriving. On the other hand, with so many different political entities, a major change in one area could have far-reaching repercussions for the overall trade system.

6.2 Long-distance trade during the AoE

During the AoE, long-distance trade changed, reflecting greater and more far-reaching movement. Some developments played decisive roles, such as the domestication of the camel, which opened up new routes across tvhe Arabian desert (Sapir-Hen and Ben-Yosef 2013); similarly, improvements in astronomy, perhaps made by the Babylonians, and in navigation techniques, often attributed to the Phoenicians, in the 1st millennium BCE [BC] greatly improved long-distance and open-sea navigation (Wachsmann 2009: 299–300). Evidence of advanced technology, which could be used to improve navigation, comes from the so-called Antikythera mechanism dated to the 3rd – 2nd c BCE [BC], which was a mechanical device that could predict astronomical positions (Carman and Evans 2014). Furthermore, the discovery of the monsoon wind in the Hellenistic period contributed to the intensification of maritime contacts with India (McLaughlin 2010: 41). Beyond the means of transport, an important innovation in the AoE was the introduction of coinage for trade trans- actions, which made them quicker and safer and meant that they were backed by government institutions. Although these innovations had a fundamental role in shaping long-distance trade during the AoE, large empires also, in our opinion, permitted the establishment of wider, longer- lasting and faster connections between distant places than in previous eras. With fewer political entities over long distances, and hence fewer political actors, there were fewer political disruptions, and so transactions became simpler, at least politically. The movement of products to more distant locations and at greater intensities suggests that movement had become easier in general. Such trade acts as a possible proxy…for the fact that populations could move more easily to more distant regions. To show how movement of products changed during the AoE, our analysis will focus on the trade of frankincense, myrrh and pepper, and coin distribution.

6.2.1 the frankincense and myrrh trade

Frankincense (Boswellia) and myrrh (Commiphora) trees grow only in Oman and Yemen and on the Somalian coasts. Their resins, if burnt, generate intense aromas, which were appreciated in many cultures for cultic and funerary rituals; they were also used for domestic, cosmetic and medical purposes (Groom 2002; C. Singer 2007: 6–8). In the Bronze Age, the frankincense used in Egypt was sourced from a region the Egyptians called the ‘Land of Punt’, whose identity is not clear, but it may have been northern Somalia (C. Singer 2007: 5). It is, however, only in the Iron Age, when camels became omnipresent in records, that caravans from Arabia loaded with frankincense and myrrh reached the Levant, where the merchants sold these products to a wide clientele. Assyrian written sources first mention Arabian caravans active in Syria, in the area of Damascus, during the reign of Shalmaneser III (858–824 BCE [BC]), and such activities became increasingly recorded in the Assyrian annals (Byrne 2003: 12; Potts 2010: 128–9; Zadok 1981).

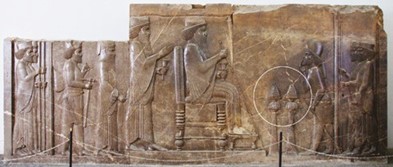

Frankincense and myrrh were burnt in burners, also called censers, made of different materials, including metal, pottery, limestone and chalk (Figure 6.3); during the Late Iron Age and Achaemenid periods, such burners can be found in Arabia, the Southern Levant, Persia and Mesopotamia (Shea 1983; Millard 1984; Invernizzi 1997a; Hassell 2005). The Nabateans played a crucial role in controlling the aromatics trade from Arabia to the Levant, in particular between the 1st – 3rd c CE [AD] (Erickson-Gini and Israel 2013). Some evidence suggests that by the Achaemenid period frankincense may have reached Central Asia, as indicated by textiles from the Pazyryk burials in the Altai Mountains between Khazakhstan and Mongolia, on which Persian-style censers are represented (Rubinson 1990).

- Figure 6.3 Relief from the ‘Treasury’ at Persepolis. The Great King Darius I (ca. 550–486 BCE) is shown on the throne with two incense burners (circled) on tall stands before him (after Davey 2010)

In the 1st c CE [AD], during the Parthian era, some censers were also found among the grave goods of Tappeh Hemat Salaleh in Azerbaijan (Curtis 2000: Fig. 8). During this period, the first indication of frankincense traded to China is found in written sources (Kauz 2010:131), and some incense burners have been recovered in China (Bulling 1972). This is also the period in which diplomatic contacts between Rome and China were established, which favoured trade exchange in several products along with silk; the trade routes were later called the Silk Road (J. Hill 2009; McLaughlin 2010).

Along these trade routes, many important caravan cities flourished. In the Near East, the most famous of these were Palmyra (in Syria), Hatra (Northern Mesopotamia) and Charax (Southern Mesopotamia; Frye 1992). The Parthian Empire, thanks to its location between the Mediterranean and Central Asia, had a crucial role in controlling these roads. The Parthian Stations (Isidore of Charax 1914), dated to the 1st c CE [AD], describes the main land routes from Central Mesopotamia, where the main cities of Babylon, Seleucia and Ctesiphon…were located, to Central Asia. These roads passed to Iran, through Kermanshah, Hamadan and Tehran, then east towards the Parthian capital of Hecatompylos. From here, they continued through Khorasan to Herat, where they split into two branches, the northern branch leading to Merv and Sogdiana or northeast to Bactria and then China, the southern branch to north India (Frye 1992). Along these roads, the cities of Begram (in mod- ern Afghanistan) and Taxila (in modern Pakistan) have yielded large quantities of Roman and Parthian material along with Indian and Chinese items (Tomber 2008: 122–4), which bear witness to the rich- ness of commercial exchanges along the Silk Road. Under the Sasanian Empire, trade exchanges along the Silk Road continued, demonstrating an important economic dimension of the Empire (Daryaee 2013: 136–8). In fact, even as empires fell and were replaced, the Silk Road continued to thrive, with occasional disruptions, and it was only after the economic changes brought about by improved seaborne navigation, the discovery of the New World, and European repositioning in trade links in the 15th c CE [AD] and later that the Silk Road diminished in importance (Tucker 2015: 216).

The Silk Road, thus, was critical in the trade of aromatics, and these products became some of the most desired foreign products in many states and empires in the Old World. The popularity of frankincense and myrrh was especially great in the westernmost parts of the Old World; in the Roman Empire (C. Singer 2007: 7) one can trace evidence of their presence as far away as Britain. Chemical analyses of resins found in late Roman tombs confirm that these resins were indeed frankincense from South Arabian sources (Brettell, Schotsmans, Rogers et al. 2015).

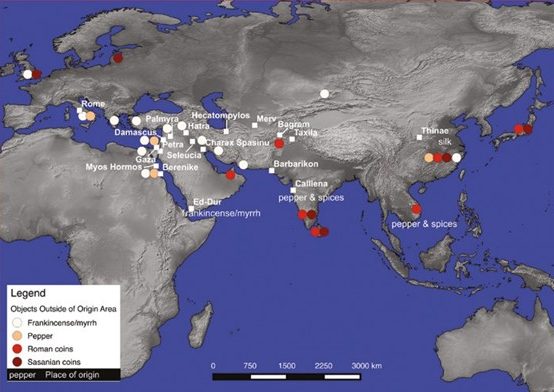

In summary, the aromatics from Arabia demonstrate that these products became truly global by spanning the extent of the Old World, something not seen in earlier pre-AoE trade (Figure 6.4). The trade network in aromatics and other products connected distant regions stretching from China to Western Europe. This trade seems to have started as early as the Iron Age, and it continued and expanded throughout the AoE, reaching a zenith perhaps from the 2nd c BCE [BC] to the 2nd c CE [AD], although heavy trade activity along international routes continued well after this period (C. Singer 2007: 7). It is noteworthy, however, that between the 2nd c BCE [BC] to the 2nd c CE [AD], there were three or at most four large empires that spanned the area between Europe and China (i.e., the Roman, Parthian, Kushana and Han Empires). Merchants could therefore cover long distances yet cross few political borders, which may explain why trade activity throughout the Old World reached a high point. Also, travellers crossing such long distances could make themselves understood by people of different ethnic origins by use a small number of international languages. For example, Greek could be used throughout much of the Mediterranean, and Aramaic across the Near East to Central Asia…Moreover, the stability of the large empires granted this network long periods of activity. Even when the imperial political system changed (for example, from the Parthian to the Sasanian Empire, and from the Roman to the Byzantine Empire), the overall trade system was not impacted to the point where there was extensive disruption of trade contacts lasting for long periods, as was the case during the Bronze Age. The situation in Western Europe after the collapse of the Roman Empire in the 5th c CE [AD] may have caused a long-term partial disruption of trade in the Old World; however, trade connections between the Byzantine Empire and Western Europe continued despite the establishment of the Germanic kingdoms within the territory of the former Western Roman Empire (Drauschke 2007).

- Figure 6.4 Map showing the distribution of frankincense and myrrh, pepper and Roman and Sasanian coins outside their home regions

6.2.2 Pepper and the Indian Ocean trade

Pepper was a sought-after spice in the AoE (see, e.g., Pliny 2006: book 12.14). It came from India and reached the Mediterranean via maritime routes along the Near Eastern and Egyptian coasts. In India, two species of pepper were available, black pepper (Piper nigrum) and long pepper (Piper longum; Tomber 2008: 55). Pepper, and other spices such as cinnamon and cassia (the former from west India, the latter from Sri Lanka, Southeast Asia and China; see Tomber 2008: 54), are also mentioned in the Periplus Maris Erythraei, a 1st c CE [AD] text written by a merchant from Alexandria, Egypt, that provides first-hand information about the intense exchange of products from India via the Indian Ocean and the Red Sea. The trade accounts mention important ports and trade winds (Casson 1989). In the Far East, pepper eventually reached China during Late Antiquity, becoming part of culinary practice in that country (Adshead 1995: 93).

Archaeologically, trade between India and the Mediterranean is evidenced by the ports excavated along the Egyptian coast of the Red Sea, such as Myos Hormos (1st – 3rd c CE [AD]) and Berenike (3rd c BCE [BC] to the 6th c CE [AD]; Tomber 2008: 58–65; Sidebotham 2011). Remains from Berenike, in particular, are evidence of intense trade activities at this port, with imports from India, the Mediterranean and Arabia, including pots for pepper, and precious and semi-precious stones such as carnelian (Tomber 2008: 71). Of particular interest is a bead from Java recovered at this site, which indicates the extension of the trade network as far as Southeast Asia (Francis 2007). On the other side of the Red Sea, the ports of Clysma (modern Suez), Aila (modern Aqaba) and Leuke Kome also had important roles in long-distance exchange up to the 4th – 5th c CE [AD] (Tomber 2008: 66–70). Further east, in the Persian Gulf, ports were involved in the Indian Ocean trade, under the control of the Parthian and later the Sasanian Empires (Whitehouse and Williamson 1973). For example, the site of Ed Dur (1st c BCE [BC] to the early 2nd c CE [AD]), located in the Oman Peninsula, yielded material such as coins and glass of Roman, Nabatean, Parthian and Indian origins; glass beads from Sri Lanka and Tanzania were also found (Haerinck 1998).

Finally, the Indian Ocean trade also brought Roman and Near Eastern materials to India and Sri Lanka. Here, Roman and Parthian/ Sasanian pottery, and other material from both the Mediterranean and Mesopotamia (e.g., glass, bullae), were recovered (Tomber 2008: 117–51; Frye 1992). This material spans the period from the 1st c BCE [BC] to 6th c CE [AD], with some short chronological gaps and changes in the distribution patterns across the region through time (Figure 6.4).

6.2.3 Coinage

During the AoE, trade was increasingly conducted on a monetary basis. Coins were probably introduced in the mid-7th c BCE [BC] in Lydia (west Anatolia) and quickly spread across the Near East and beyond, where several cities struck coins (Manning 2013: 2). Although it appears that coins were initially introduced to make the payment of mercenaries easier (Manning 2013: 2), they became more and more common in all economic transactions through time. Thanks to their great spread, coins also became a vehicle of imperial political propaganda.

Coin distribution can act as a proxy for the extension of trade exchanges during the AoE, though it should be borne in mind that coins, especially those made of precious metals, could circulate as valuable items rather than as a means of transactions (Figure 6.4). Within the Achaemenid Empire, coins appear to have been predominantly used for trade transactions with Greeks along the Levantine coasts, which would also explain why Persian coins are generally found towards the west, out- side the reach of the Achaemenid Empire, in Italy, Macedonia and Greece (Alram 1994). Towards the east, Persian coins appear to have been used less frequently, though a hoard containing Greek, Persian and Indian coins was found near Khabul (Afghanistan) in 1993 CE [AD] which indicated that, albeit more sporadically, Persian coins too had travelled to Central Asia (Schlumberger 1953). It was during the Seleucid Empire that coins spread considerably across the Near East, because the Seleucids incentivized coin payments for their military, and therefore needed to collect taxes in coins. Many mints were established across their empire to guarantee coin supply, and, consequently, more coins were used in markets for everyday economic transactions (Aperghis 2004: 29–32). In the following periods this trend continued, reaching its peak under the Sasanian Empire. Sasanian coins were used for trade as far away as China, reaching the River Volga in Russia, and the Baltic Sea (Frye 1992; Thierry 1993). They were also found in Japan along with other Sasanian objects (Sugimura 2008), and along the coasts of the Persian Gulf and in India (Whitehouse and Williamson 1973; Potts 2010: 65–82). Sasanian merchants also engaged in trade with the rival Romans (and later Byzantines); in some cases international treaties were implemented to regulate exchange (Daryaee 2013:140; Drijvers 2009: 449). Sasanian coins in Britain, although rarely found, seem to indicate the wide scope of Sasanian–Roman trade relations (Herepath 2002). Finally, coin dis- tribution gives us a glimpse into the wide reach of Roman commercial links, as witnessed by Roman and later Byzantine coins found in China, in Indonesia, and as far afield as Japan; Chinese texts that refer to trade relations with the Romans also suggest that coins should be expected this far east (Young 2001; J. Hill 2009; Kyodo 2016).

6.3 Private corporations during the AoE

Our information about private companies directly involved in long- distance trade and the economy increases with the AoE. The economy of the Achaemenid Empire has long been recognized as a mixture of the royal, temple and private sectors, the latter particularly attested on the Levantine coasts where Phoenician cities produced and traded mainly textile dye and glass (Dandamaev 1989). Important evidence for the pri- vate sector in the economy under the Neo-Babylonian and Achaemenid Empires comes from the private archives of families actively involved in different economic sectors and trade. Examples are the Egibi family of Babylon, the Ea-iluta-bani of Borsippa, and the fifth-century BCE Murashu family of Nippur (Nemet-Nejat 1998: 226). The tablets found in the Murashu archive indicate that this family was involved in a wide range of economic activities, including land management, money lending, the keeping of deposits, trade and tax collection (the last on behalf of the state); this family acted as a firm, hired agents, and stipulated agreements with several individuals, thus representing one of the first forms of a banking system that included not just one location or a branch but was found in many areas throughout Southern Mesopotamia and into Elam (Dandamayev 1988).

Information about the private sector in the economy and trade is again scarce during the Seleucid and Parthian periods; this is mostly because the number of documents that have survived is minute. Under the Sasanian Empire, however, we learn from written sources (e.g., Syriac law books) that trade was mainly under the control of private families and of companies regulated by state and religious laws (Frye 1992). Moreover, although in Persia itself merchants did not seem to be of high status, in Central Asia written texts reveal that merchants were at the top of the social ladder, particularly in areas such as Bukhara and Samarkand, where private initiative was essential to the construction of canals and other infrastructure with an economic purpose (Frye 1992). An interesting feature of the AoE economy is the importance of religious communities, in particular Christian ones, involved in long- distance exchange. The spread of universal religions under empires…appears to have allowed the creation of trusted links between distant communities and increased cohesion between different ethnic groups who shared the same religious beliefs, and helped to facilitate and set the conditions for international trade on a global scale (Dark 2007). This is evidenced by, for example, 5th – 6th c CE [AD] texts that indicate direct or indirect involvement of Christian churches and clergy in the trade with India (Tomber 2008: 168–9).

6.4 Merchant colonies

Some evidence regarding the intensification of population movement in the AoE comes from merchant colonies. In section 6.2 we saw that during the AoE the international trade network reached an unprecedented extent; hence one could wonder whether this phenomenon was mainly due to the movement of traded objects ‘down the line’, that is, through many intermediate passages, or via merchants who established colonies far from their homeland. In section 6.1 we spoke about the stable presence of Assyrian merchants in Kanesh, in Central Anatolia, located about 1000 km [621.37 mi] away from Assur, and their trade activities, dated to the early 2nd millennium BCE [BC]. During the Late Bronze Age, evidence of the presence of merchant colonies comes from Ugarit, from where texts indicate the stable presence of merchants from Akko, Ashdod and Ashkelon (Vidal 2006). Canaanite merchants are attested as a stable presence in Crete (at Kommos) and Cyprus (at Hala Sultan Tekke), as are Assyrian merchants in Sidon and other cities on the Levantine coasts, for the trade of textiles (Aubet 2000).

These cases indicate that merchant colonies existed during the pre-AoE, though during the AoE the evidence increases and the phenomenon seems to spread to a larger area. In the 1st millennium BCE [BC] the phenomenon of Phoenician colonization greatly expanded the presence of Phoenician merchants across the Mediterranean (Aubet 2001), which allowed the Phoenician cities on the mainland to grow economically, thus becoming over time the target of Assyrian indirect or direct control; Greek merchants too were widely present across the Mediterranean: Greek emporia were founded in Egypt (for example at Naukratis), and a stable presence of Greek merchants can also be inferred in some Levantine cities, for example Al Mina (Fantalkin 2006 []). This trend increases during the Hellenistic period, under the Seleucid Empire, when we discover many Greek cities being founded, across the Near East as far as Central Asia, in which elements of Greek and local Near Eastern cultures blend together…This trend continues under the Sasanian Empire, with Sasanian merchant colonies attested in the Persian Gulf, Sri Lanka and Malaysia, and as far as China (Daryaee 2013: 139; 2009: 64). Similarly, Roman, Jewish and Christian settlers from the Roman Empire are attested in India between the 2nd – 5th c CE [AD] as being involved in commercial affairs (Curtin 1984: 90–109; see also above).

This evidence suggests that the phenomenon of merchant colonies, though not new in the AoE, greatly increased during this period, follow- ing the expansion of the trade network. This phenomenon should be framed within the establishment of the large empires of the AoE, which created more favourable conditions for merchants to move across wider areas and settle far from their homelands.

6.5 Speed of Travel

Another difference between pre-AoE and AoE trade connections is the speed of travel. Evidence about the speed at which people travelled before and during the AoE comes from different sources, some dealing with long-distance trade and others (more numerous) with state correspondence and military campaigns. The Old Assyrian caravan trade connecting Assur to Kanesh in the 2nd millennium BCE [BC] (see above) covered a distance of about 1100 km [683.51 mi] in 42 days (see Barjamovic 2011: 15; Larsen 2015: 175–6), which corresponds to about 26 km [16.16 mi] a day. About 30 km [18.64 mi] a day is the average distance travelled by pack donkeys in antiquity (Moorey 1994: 12).

The Old Assyrian caravan trade can be compared with later evidence regarding speed of travel during the AoE. In the Neo-Assyrian Empire (c. 900–612 BCE [BC]), a system of relay was introduced to deliver letters. Estimates indicate that this system could cover a distance of about 700 km [435 mi], from Que (in the modern Adana region) to the Assyrian heartland (northern Iraq), in about five days (Radner 2014b: 74), which corresponds to 140 km [87 mi] a day. Furthermore, it was mentioned earlier that long-distance routes were direct or relatively straight as they connected distant key cities with the Assyrian capitals (Altaweel 2008: Plates 16–17), while routes in the pre-AoE, such as the Assyrian trade route from Ashur, may have taken less direct routes (Larsen 2015: 179). The less direct Assyrian trade routes could have avoided taxation or even conflict in cities along the way. In fact, imagery showing remnants of ancient roads in the Jazira and Khabur Triangle regions of Northern Mesopotamia largely shows short or nearest-neighbour route connections between sites (Ur 2003). For other AoE cities, the trend towards trade routes that are direct and long-distance is evident from satellite imagery for sites such as Hatra (Altaweel and Hauser 2004: 64). In effect, trade, or movement of goods in general, in the AoE began to show physical evidence of being not only long-distance but also more direct than in earlier periods.

In the Achaemenid Empire, mounted couriers of the postal service, the Angarium, riding along the Royal Road from Susa to Sardis, could travel about 2700 km [1677.7 mi] in seven days, according to Herodotus (Kia 2016: 127). This indicates an impressive speed of nearly 386 km [240 km] a day. Colburn (2013) revised Herodotus’ affirmation and calculated that the Angarium would probably take around 12 days to cover such a distance based on the parallel with the more modern Pony Express service. This gives 225 km [140 mi] a day, a value which, while not as high as Herodotus’ figure, clearly indicates a swift connection between the cities.

Such high figures for travel speed in the Neo-Assyrian and Achaemenid Empires were due to different factors. First, the material transported by means of these very quick connections was essentially diplomatic, so it was crucial that it was transmitted as fast as possible; on the other hand, trade connections may have been slower. According to Herodotus, for example, the journey from Susa to Sardis took 90 days for a normal traveller, which is about 30 km [18.64 mi] a day, similar to the Old Assyrian caravans. Xenophon, however, informs us that the same distance could be covered in half the time by a normal traveller (which is 60 km a day; Colburn 2013: 42). After the Achaemenid Empire, information about travel speed comes from the rapidity with which the news of the king’s or emperor’s death spread. From an Idumaean ostracon bearing a date in the first year of the reign of Philip III (17 June 323 BCE [BC]), it can be inferred that the news of Alexander’s death reached Idumaea (modern Negev, south Israel) from Babylon after one week (Colburn 2013: 42), covering about 1000 km [621.37 mi] in a straight line, that is, about 140 km [87 mi] a day. Such a high figure might be comparable with the speedy communication witnessed during the Neo-Assyrian Empire.

In the Roman Empire, it took 30 days to communicate the emperor’s death from Italy to Egypt in summer when the sea was navigable, that is, about 62 km [38.56 mi] per day, which is slower than the postal service of the Achaemenid Empire (Colburn 2013: 47–8). On land, communication within the Roman Empire travelled at about 75 km [46.6 km] per day, which meant that it could take about 17.5 days to travel from Rome to Colchester in Roman Britain (about 1300 km; Colburn 2013: 47–8). The figures for the Roman Empire’s speed of travel are not as high as those of the Achaemenid Empire, which is probably due to the different geographies of the two empires, but they are still greater than the average Old Assyrian caravan trade speed of the 2nd millennium BCE [BC].

Chinese sources of the 1st – 2nd c CE [AD] are also useful for inferences about speed travel. When referring to the Parthian Empire, they report that the route from Hecatompylos, in Parthia, to Chaldea was about 3580 km [222.4509 mi] long and could be covered in about 60 days, giving 60 km [37.28 mi] a day (Hirth 1885: 36–40). This figure is close to that given by Xenophon for the Achaemenid Empire and those available for the Roman Empire.

While, clearly, horses would have made travel in the AoE far faster than the donkey-based caravan travel of the pre-AoE, differences in the route systems also made a difference. In the pre-AoE, routes were not direct and travel sometimes had to bypass particular areas. In the AoE, both maritime and land travel became direct. This was due both to technical changes, in navigation and the greater use of horses, and to the possibility of covering vast distances without encountering disruption from the fact that there were many states and political entities.

6.6 Conclusion: the factors that distinguish pre-AoE and AoE trade

In the previous sections, it was shown that exchange of goods across long distances is not an invention of the AoE; however, AoE trade shows globalized traits, in that goods moved through much of the known world, trade was run by private enterprise and government support, and the speed of trade probably increased. The scale of trade during the AoE became far larger than in previous periods, with trade connections crossing Eurasia, including South Asia, from west to east. Both land and maritime routes developed, and exchanges across these routes peaked during the AoE. The establishment of these long-distance trade corridors appears to be a more stable phenomenon, suffering only marginally from the collapses of empires and their replacement by other empires. As an example, both the Silk Road and the Indian Ocean trade routes remained active well beyond the AoE, into the modern era, when the discovery of the Americas, among other factors, drastically changed the trade scenario and opened up new opportunities for Western European countries in the form of long-distance trade across the Atlantic Ocean. What this shows is that movement in general probably became easier during the AoE, rarely being interrupted during this period. As the circulation of objects became easier, we should expect that population movement would also be easier. In effect, the movement of rare objects over geater distances shows that movement generally became easier as the political landscape favoured larger states….evidence of new urban settlement patterns and of foreign populations intermixing in cities demonstrates that there was probably movement of population. If such movement occurred, it is likely that objects, too, moved more easily along trade routes. This is exactly what one sees throughout the AoE, in places where political disruption did not have long-term effects on movement.

Although evidence about the speed of travel and trade is not abundant, where information is primarily derived from sources dealing mainly with couriers one can conclude that AoE states were able not only to move items to more distant areas, but also to send them more rapidly, probably because of the protection and stability that empires offered such transactions. One could conclude that, compared with the 30 km a day of the Old Assyrian caravans, under the AoE a speed of 60 km a day may have been more common, with very high peaks for the Achaemenid postal system; the transmission of very important information (e.g., the king’s death) may have been even swifter. One of the main reasons we see higher communication speed was that large empires built roads and infrastructure (see, e.g., Altaweel 2008; Waters 2014: 111), and facilitated the movement of people across different regions by removing political borders. In the pre-AoE, political boundaries created more obstacles to extending the distance over which trade could take place, and made trade more vulnerable to political vicissitudes. As acknowledged by other scholars, quick connections across long distances were an essential part of an empire’s communication strategy and internal cohesion (Radner 2014b: 1; Colburn 2013: 30). The benefit of these connections is that they helped create infrastructure that allowed trade to move more quickly and over greater distances.

The keys to the success of the AoE’s long-distance trade, including its great scope and stability, are to be found in the effect of the imperial systems the Near East fostered. Incentives to trade were created for more individuals to participate in these systems as they became increasingly integrated into diverse societies. People from a variety of ethnic backgrounds now lived far from their original homelands, allowing trade connections to develop at more distant locations. More importantly, the political climate made movement not only possible but also easier, and allowed people to participate in trade interactions that were probably influenced by private individuals as well as government bodies. Movement of people and their concentration in larger cities created large markets that demanded staples as well as luxury products. Despite the consequent creation of more sparsely populated areas in parts of the Near East…empires facilitated rapid contacts over long distances by means of road systems and postal systems, and by drastically reducing or removing social barriers across the Near East…[L]anguage, another barrier, became less of a factor in the AoE. Overall, these social possibilities and some technical innovation permitted movement of goods that reached a wider clientele, in more distant areas, much faster than in earlier periods. Thus, the basis of a globalized and intercultural trade was laid down during the AoE. Although the empires of the AoE were concerned with their economies and trade, and exercised firm control over coinage and taxation, private families organized themselves into firms that greatly developed during the AoE and laid the basis of a modern banking and financial system. The emergence of universal religions during the AoE probably facilitated the establishment and maintenance of long-distance, intercultural trade contacts by creating common faiths that could be shared and used for business.

= "Age of Empires"

BCE = Before Common Era (essentially equivalent to BC)

CE = Common Era (essentially equivalent to AD)

* see The Myth of the BC/AD Dating System for more information

"around," "approximately," with respect to dates

ex: I moved to Indianapolis c. 2013 = "I moved to Indianapolis around 2013"