8 [Reading] T01-L02-A0: Medusa and Women in Power

“Women in Power.”

Beard, M. 2017. “Women in Power.” London Review of Books 39(6).

NOTES ON THIS TEXT

This essay was published in 2017 as part of a lecture series by Mary Beard, a famous British Classicist who has authored several best sellers for a non-academic audience. For this class, the broader point is not whether Dr. Beard’s analysis of modern power structures is accurate (she’s a Classicist, not a sociologist), but how she interprets powerful females from the ancient world, particularly Medusa.

- I have selected parts of the essay for length, relevance, and clarity.

- I have also reformatted some elements (particularly the dates) for clarity.

If you need a more general English dictionary to look up unfamiliar vocabulary, I recommend Merriam-Webster Online.

In 1915 Charlotte Perkins Gilman published a funny but unsettling story called Herland. As the title hints, it’s a fantasy about a nation of women – and women only – that has existed for two thousand years in some remote, still unexplored part of the globe. A magnificent utopia: clean and tidy, collaborative, peaceful (even the cats have stopped killing the birds), brilliantly organised in everything from its sustainable agriculture and delicious food to its social services and education. And it all depends on one miraculous innovation. At the very beginning of its history, the founding mothers had somehow perfected the technique of parthenogenesis. The practical details are a bit unclear, but the women somehow just gave birth to baby girls, with no intervention from men at all. There was no sex in Herland.

[ ... ]

As well as describing imaginary communities of women doing things their way, Herland raises bigger questions, from knowing how to recognise female power to the sometimes funny, sometimes frightening stories we tell ourselves about it, and indeed have told ourselves about it, in the West at least, for thousands of years.

I’ve talked before about the ways women get silenced in public discourse. And there’s plenty of that silencing still going on. We need only think of Elizabeth Warren being prevented a few weeks ago from reading out a letter by Coretta Scott King in the US Senate. [ ... ]What was extraordinary on that occasion wasn’t only that she was silenced and formally excluded from the debate (I don’t know enough about the rules of procedure in the Senate to have a sense of how justified, or not, that was); but that several men over the next couple of days did read the letter out and were neither excluded nor shut up. True, they were trying to support Warren. But the rules of speech that applied to her didn’t appear to apply to Bernie Sanders, or the three other male senators who did the same.

The right to be heard is crucially important. But I want to think more generally about how we have learned to look at women who exercise power, or try to; I want to explore the cultural underpinnings of misogyny in politics or the workplace, and its forms (what kind of misogyny, aimed at what or whom, using what words or images, and with what effects); and I want to think harder about how and why the conventional definitions of “power” (or for that matter of “knowledge,” “expertise” and “authority”) that we carry round in our heads have tended to exclude women.

It is happily the case that in 2017 there are more women in what we would all probably agree are “powerful” positions than there were ten, let alone fifty years ago. Whether that is as politicians, police commissioners, CEOs, judges or whatever, it’s still a clear minority – but there are more. (If you want some figures, around 4 per cent of UK MPs were women in the 1970s; around 30 per cent are now.) But my basic premise is that our mental, cultural template for a powerful person remains resolutely male...

What follows from this is that women are still perceived as belonging outside power. Whether we sincerely want them to get to the inside of it or whether, by various often unconscious means, we cast women as interlopers when they make it...the shared metaphors we use of female access to power – knocking on the door, storming the citadel, smashing the glass ceiling, or just giving them a leg up – underline female exteriority. Women in power are seen as breaking down barriers, or alternatively as taking something to which they are not quite entitled. A headline in the Times in early January captured this wonderfully. Above an article reporting on the possibility that women might soon gain the positions of Metropolitan Police commissioner, chair of the BBC Trust, and bishop of London, it read: “Women Prepare for a Power Grab in Church, Police and BBC.”…Now, I realise that headline writers are paid to grab attention. But the idea that even under those circumstances you could present the prospect of a woman becoming bishop of London as a “power grab”...is a sure sign that we need to look a lot more carefully at our cultural assumptions about women’s relationship with power. Workplace nurseries, family-friendly hours, mentoring schemes and all those practical things are importantly enabling, but they are only part of what we need to be doing. If we want to give women as a gender – and not just in the shape of a few determined individuals – their place on the inside of the structures of power, we have to think harder about how and why we think as we do. If there is a cultural template, which works to disempower women, what exactly is it and where do we get it from?

At this point, it may be useful to start thinking about the classical world. More often than we may realise, and in sometimes quite shocking ways, we are still using Greek idioms to represent the idea of women in, and out of, power. There is at first sight a rather impressive array of powerful female characters in the repertoire of Greek myth and storytelling. In real life, ancient women had no formal political rights, and precious little economic or social independence; in some cities, such as Athens, respectable married women were almost never seen outside the home. But Athenian drama in particular, and the Greek imagination more generally, has offered our imaginations a series of unforgettable women: Medea, Clytemnestra, Antigone.

They are not, however, role models – far from it. For the most part, they are portrayed as abusers rather than users of power. They take it illegitimately, in a way that leads to chaos, to the fracture of the state, to death and destruction. They are monstrous hybrids, who aren’t – in the Greek sense – women at all. And the unflinching logic of their stories is that they must be disempowered, put back in their place. In fact, it is the unquestionable mess that women make of power in Greek myth that justifies their exclusion from it in real life, and justifies the rule of men...

Athena, the patron deity of the city, is often brought in on the positive side too. Doesn’t the simple fact that she was female suggest a more nuanced version of the imagined sphere of women’s influence? I’m afraid not.

[ ... ]

[I]t’s true that in those binary charts of gods and goddesses that we make for ourselves, [Athena] appears on the female side. But the crucial thing about her in the ancient context is that she is another of those difficult hybrids. But the crucial thing about her in the ancient context is that she is another of those difficult hybrids. In the Greek sense she’s not a woman at all. For a start she’s dressed as a warrior, when fighting was exclusively male work...Then she’s a virgin, when the raison d’être of the female sex was breeding new citizens. And she wasn’t even born of a mother but directly from the head of her father, Zeus. It was almost as if Athena, woman or not, offered a glimpse of an ideal male world in which women could not just be kept in their place but dispensed with entirely.

The point is simple but important: if we go back to the beginnings of Western history we find a radical separation – real, cultural and imaginary – between women and power. But one item of Athena’s costume brings this right up to our own day. On most images of the goddess, at the very centre of her body armour, fixed onto her breastplate, is the image of a female head, with writhing snakes for hair. This is the head of Medusa, one of three mythical sisters known as the Gorgons, and it was one of the most potent ancient symbols of male mastery of the dangers that the very possibility of female power represented. It’s no accident that we find her decapitated, her head proudly paraded as an accessory by this decidedly un-female female deity.

There are many ancient variations on Medusa’s story. One famous version has her as a beautiful woman raped by Poseidon in a temple of Athena, who promptly transformed her, as punishment for the sacrilege, into a monstrous creature with a deadly capacity to turn to stone anyone who looked at her face. It later became the task of the hero Perseus to kill this woman, and he cut her head off using his shiny shield as a mirror so as to avoid having to look directly at her. At first he used the head as a weapon since – even in death – it retained the capacity to petrify; but he then presented it to Athena, who displayed it on her own armour (one message being: take care not to look too directly at the goddess).

It doesn’t need Freud to see those snaky locks as an implied claim to phallic power. This is the classic myth in which the dominance of the male is violently reasserted against the illegitimate power of the woman. And Western literature, culture and art have repeatedly returned to it in those terms. The bleeding head of Medusa is a familiar sight among our own modern masterpieces, often loaded with questions about the power of the artist to represent an object at which no one should look. In 1598 Caravaggio did an extraordinary version of the decapitated head with his own features, so it is said, screaming in horror, blood pouring out, the snakes still writhing. A few decades earlier Cellini made a large bronze statue of Perseus which still stands in the Piazza della Signoria in Florence: the hero is depicted trampling on the mangled corpse of Medusa, and holding her head up in the air, again with the blood and the gunge pouring out of it.

What’s extraordinary is that this beheading remains even now a cultural symbol of opposition to women’s power. Angela Merkel’s features have again and again been superimposed on Caravaggio’s image. In one of the more silly outbursts in this vein, a column in the magazine of the Police Federation called Theresa May the “Medusa of Maidenhead” during her time as home secretary. “The Medusa comparison might be a bit strong,” the Daily Express responded: “We all know that Mrs May has beautifully coiffed hair.” But May got off lightly compared with Dilma Rousseff, who had to open a major Caravaggio show in São Paolo. The Medusa was naturally in it, and Rousseff standing in front of the very painting proved an irresistible photo opportunity.

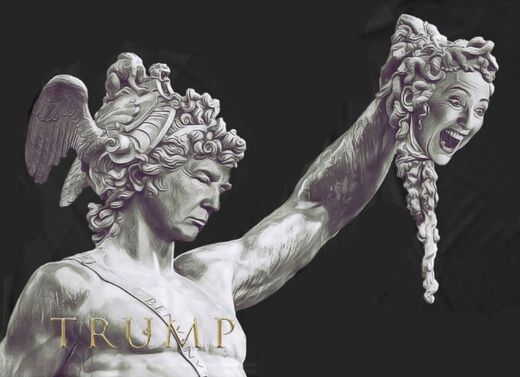

But it’s with Hillary Clinton that we see the Medusa theme at its starkest and nastiest. Predictably Trump’s supporters produced a great number of images showing her with snaky locks. But the most horribly memorable of them adapted Cellini’s bronze, a much better fit than the Caravaggio because it wasn’t just a head: it also included the heroic male adversary and killer. All you needed to do was superimpose Trump’s face on that of Perseus, and give Clinton’s features to the severed head (in the interests of taste, I guess, the mangled body on which Perseus tramples in the original was omitted). It’s true that if you crawl around some of the darker recesses of the web, you can find some very unpleasant images of Obama, but they’re very dark recesses. This scene of Perseus-Trump brandishing the dripping, oozing head of Medusa-Clinton was very much part of the everyday, domestic American decorative world: you could buy it on T-shirts and tank tops, on coffee mugs, on laptop sleeves and tote bags (sometimes with the logo triumph, sometimes trump). It may take a moment or two to take in that normalisation of gendered violence, but if you were ever doubtful about the extent to which the exclusion of women from power is culturally embedded or unsure of the continued strength of classical ways of formulating and justifying it – well, I give you Trump and Clinton, Perseus and Medusa, and rest my case.

- Hillary Clinton portrayed as Medusa, with Trump as Perseus.

[ ... ]

This symbol indicates where I have omitted some material from the original work.

United Kingdom Members of Parliament (elected representatives)