1 INTRODUCTION

WHAT DO YOU NEED?

During my first six months as director, I walked around campus to introduce myself to students, faculty, and staff in all the schools although we were based in the College of Arts and Sciences. It was not uncommon for me to invite anyone I met at a meeting or on the bus to “drop by and stay awhile” and to answer the question: What do you need?

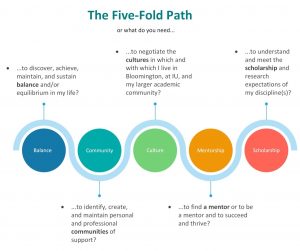

By the end of my first semester, students had filled a 12-foot wall in my office with responses. These small brightly colored pieces of paper would become the basis for the Five-Fold Path, the five tenets that guide what The GMC would do over the next seven years. After I and my first two graduate assistants sat for several days reading what had been shared with us, we concluded that what students needed fit into five categories: balance, community, culture, mentorship, and scholarship.

Asking, “What do you need?” was not as simple as it appeared. Anyone who dared answer it had to reflect on what they wanted, their reality, and the sometimes-contentious intersections between them. At times, this question provoked anger and fear; at other times it initiated tears. I would learn that for students who came from communal cultures that the question was confusing or meaningless: they did not see themselves as individuals separate from their communities.

For students and faculty from historically underrepresented groups and communities of color – our primary focus – this question was also complicated and could involve (sometimes ancient and assumed) commitments to and expectations of family.

If the student and faculty identified as a woman, regardless of race, culture, religion, or sexuality, need could be shaped by those of others, leaving little space for their own. And, the violence and exclusions that accompanied gender in the academy added to the isolation and struggle of pursuing one’s degree.

At the end of the first year, it became clear that The GMC’s approach to mentoring had to be different. Mentoring for us had to intentionally consider the contexts and cultures that students carried with them into the classroom, our offices, on campus; their homes when they returned, if they could return. Mentoring had to focus on more than degree completion and research.

As a creative and scholar whose work is deeply tied to my history, i.e., the Transatlantic Slave Trade, trauma, and healing, I know all too well what it is like to be in spaces that do not welcome the personal and professional and the effect that can have on my mental health, and the well-being of one’s family and communities.

CO-CREATING PROGRAMS

With these experiences in mind, and with the help and trust of faculty and students, we began with faculty workshops about understanding how contexts shaped mentoring, the stages of mentoring, and mentoring practices (later called Let’s Talk About Mentoring). However, a series of requests and crises from students made clear that the needs of students would have to take priority.

Recall that on August 9, 2014, Michael Brown, Jr. was killed. This was just two weeks before I began my job. My first month was spent responding to questions from international students and students of color that focused on basic survival in the academy, teaching, and finding faculty who could support them and understand their cultural needs. There were also questions from white students: is the center only for students of color, and how can we get these services?

Hence, after the first year, the center temporarily put aside plans to develop a training model for faculty and became fully student-centered. Furthermore, we chose to expand our services beyond the usually mandated population – historical underrepresented students – to all graduate students, taking into account the cultural, racialized, and gendered contexts that shaped their experiences within and outside the academy.

Since the beginning, co-creation and collaboration have been an essential part of The GMC. Both are important parts of informal mentoring and professionalization; of helping students develop the diverse skills needed to practice what they research; and of inviting them to create new methodologies. This approach has led to a rich array of programs that would later be refined to focus on the following areas: weekly meditation and writing groups, semester programs such as a research roundtable and student-led discussions on being in the academy; and special programs for women of color and international students. The two defining programs for the center, however, would be our annual Trailblazers and Innovators scholar-in-residence series and the mentoring cohort.

Trailblazers and Innovators. Through Trailblazers and Innovators, we hosted emerging and established scholars of color on campus for an average of five days to share their research, personal stories, and “secrets” about publishing, seeking tenure, and doing truly innovative work without doing further harm to themselves. The series would prove popular and successful, sometimes drawing inter/national attendees. Long after their visits, scholars continued contact with students who reached out to them. After Dr. Kakali Bhattacharya’s visit, for example, students were inspired to create a two-day symposium on creative and qualitative methodologies. And, after Dr. Keisha Blain’s visit, Charleston Syllabus became the foundation for the national dialogue series Powerful Conversations on Race, created by Spirit & Place of Indianapolis.

Our goal with Trailblazers: to invite a scholar-activist-creative from a different discipline and practice every year, one who not only talked about or represented diversity but who could also speak to the developing interests of students in a changing world. We didn’t want scholars who just walked their talk. We wanted scholars who embodied the work they did, and were willing to allow their work to lead them to emergent practices that challenged them to unlearn and rethink their own disciplines.

Mentoring Cohort. The second core program, the mentoring cohort, allowed us to pair graduate students with a faculty member of their choice; both faculty and students were from historically underrepresented groups in their discipline and/or the academy. This was, perhaps, our biggest experiment. Instead of pairing students for a specified time, with faculty in their disciplines, and with one person only, we asked students What do you need? Through interviews with students and faculty, I was able to determine the best matches. Even then, however, it was up to the student and faculty member to make the final determination. If after the initial meeting they agreed to work together (or not), I honored their decision. It was also up to them when they “separated” (mentoring stage 4).

As a result, some mentor-mentee teams worked together for a semester, with the faculty providing guidance for a student’s final semester or a project. More often than not, however, student and faculty member worked together for years. The GMC’s longest formal mentoring relationship lasted for over seven years until the student graduated. After graduation, the mentor and mentee continued to work together on job searches and publications, moving into the redefinition stage of mentoring to become friends. Because the mentoring was wholistic during foundational years, the mentee on several occasions has included their mentor, myself, and other mentees in life-changing events.

The other feature of the cohort, then, that was essential: it was communal. While students and faculty were required to meet at least once a month, the cohort itself met monthly with anyone who could attend. In this way, mentoring became a group endeavor during which mentors and mentees rotated to provide a different view of a specific issue (e.g., CV revision) that they had selected. Mentors also occasionally provided workshops in their areas of expertise: e.g., conference presentations, building digital profiles, job talks, submitting publications. For many in the cohort, the approach was an opportunity to get the mentoring they needed at multiple and interdisciplinary levels: peer, colleague, faculty; across departments and schools.

MOVING FORWARD

It is 2021. August. On July 31, I officially resigned my position as founding director. I returned to complete this work during fall 2021 with assistance from Jen Park, who as of this writing is the graduate assistant and who will be graduated by the time we finish the book. For me, it is an act of love and commitment, a responsibility to complete something I started, though far from the grand thing I originally imagined. We no longer have the one-time funds that were set aside to do this, the staff, or the programs. Those who started have moved on to other projects because 2020 meant we all had to leave something and someone behind, and 2021 demands that we get back on track, even though the track is now a dirt road or no road at all.

None of us have the energy or capacity to look back and wonder how we got over. But, we do have the desire to make sure that the work of The Graduate Mentoring Center in its next iteration is able to support graduate students, faculty, and staff as much as possible.

Before I had settled in my office that first semester in 2014 – just two months after becoming the first person to ever earn a doctorate in African American and African Diaspora Studies at Indiana University – a few faculty members approached me one day at Sample Gates to say: congratulations, let me know what you need. Those same faculty members would say yes when I asked for help. They did so without knowing what helping me entailed. Students visited our office to sit and wait to see what would happen. They were patient and offered help when I had no staff. They showed up to programs, handed out flyers, and worked even when they were not paid to do so.

It is because of this community that The Graduate Mentoring Center was able to take a leap into a dream for a new way of mentoring. With the unwavering support of the University Graduate School, we were able to explore possibilities that have now become a model for others. The next stage is upon us and we welcome the new staff as they continue to grow into what the IU community of scholars need next.

We – all of us who co-created The Graduate Mentoring Center – thank you for your support and invite you to continue supporting graduate student education, growth, and success.

Maria Hamilton Abegunde, Ph.D.