Beginning with the End in Mind

When you have the opportunity to create or revise a course, it’s important to take a step back and look at it holistically before diving in. Well-organized classes with clearly structured course material are much easier for students to navigate, so making sure you have a clear and logical structure is important to your students’ success and your own peace of mind.

When you have the opportunity to create or revise a course, it’s important to take a step back and look at it holistically before diving in. Well-organized classes with clearly structured course material are much easier for students to navigate, so making sure you have a clear and logical structure is important to your students’ success and your own peace of mind.

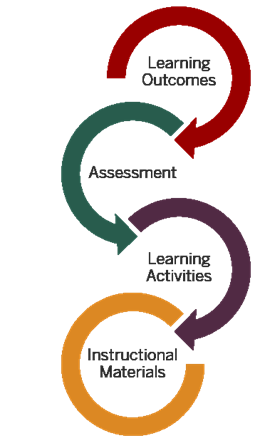

To do this, we’re going to use the backward course design model (Wiggens & McTighe, 2005), very commonly used in all levels of education. Backward course design involves answering three questions:

- What do you want the students to learn?

- How will both you and your students know if they are learning?

- What actions will both you and your students need to take for them to learn?

It’s about beginning with the end in mind.

It starts with clearly describing your desired learning objectives – what you want your students to know and be able to do at the end of the course. From there it moves “backwards” through assignments to assess how well your students know and can do these things, learning activities to give them opportunities to work with the content and skills, and instructional materials to provide the information and explanations they need to succeed.

Letting your desired learning objectives lead the course can be challenging if you’ve spent years taking and teaching courses put together based on covering content. A content-centered course starts with a list of topics (not uncommonly based on textbook chapters) and works through them over the semester focusing on covering all the things. Alternatively, a backward design course is learning-centered and begins with the answers to the three questions above.

In the following video, a University of Wisconsin faculty member describes how they are using the backward design process to improve courses.

Alignment is a big deal

The key point of backward design is that your assessments, activities, and instructional materials should all align to your desired objectives. This makes sure that what you teach, the activities and materials you use to teach, and what knowledge and skills you assess all lead to the same place. And that place is a destination both you and your students can recognize from your learning objectives. Since your learning objectives describe the “destination” you want your students to reach, it’s important that they be as clear as possible to your students. If they know where they’re going, they’re more likely to follow along the path you’ve made.

This is where things can get tricky. You have to be really clear about what you want your students to know and be able to do so that you can provide applicable practice activities and assess the extent to which they have reached the outcome. If you write a learning outcome stating they should be able to carry out pH tests of water samples, asking them to identify the second step in the process via a multiple-choice question won’t provide the evidence you need. Identifying steps on a quiz will only provide evidence that they can recognize the order of steps.

Writing clear and measurable objectives

Learning objectives focus on specific knowledge, skills, attitudes, and beliefs that you expect your students to learn, develop, or master (Suskie, 2004). They describe what you want students to know and be able to do at the end of the course. Effective learning objectives

- describe student actions, not instructor actions or passive states of being

- describe something that is observable and measurable in the context of the class

By making sure they describe student actions and are observable and measurable, students can see when they have reached their destination.

You often see objectives written using words like “know” and “understand,” neither of which are directly observable or measurable. On the other hand, if you ask students to “describe”, “identify”, “analyze”, or “evaluate” something, you have something you can observe and grade. If you’re looking for verb ideas, Bloom’s Taxonomy (pdf, 173k), and Fink’s Taxonomy of Significant Learning (pdf, 361k) are good places to start. As mentioned above, make sure to take your activities and assessments into consideration. For example, if your objective says students should be able to design an efficient project workflow, you then need to have materials that explain your criteria for effectiveness, activities that let them practice designing workflows and get feedback on their efforts, and an assessment that asks them to design a workflow that meets your effectiveness criteria.