Improving Accessibility and Usability in Written Materials

The hope is that, when faculty create materials, they take some time to think about how diverse students, including students with disabilities, would interact with them. The following video from the Centre for Teaching, Learning and Technology at the University of British Columbia discusses how accessibility and open content intersect (3:30)

“Open Dialogues: Open education and accessibility” by CTLT, University of British Columbia [Youtube] is licensed CC BY 4.0.

Since the bulk of your OER will likely be written, we’ll look at some simple practices to improve accessibility and usability when creating written materials.

Writing Style

When you write your own instructional materials you want to always keep your audience in mind. You’re writing for an audience of students at a particular level of understanding, not a journal review board. If most of your writing is scholarly journal articles, writing for a different audience can be challenging. For your writing to be more approachable, it helps to write

- in 2nd person, using you and your,

- in a conversational tone, and

- at an appropriate reading level for your students

If you aren’t sure about your reading level, run part of your text through a readability checker. You’re looking for a score around 50-60 with higher numbers meaning easier to read. The text on this page scored a 61. The main problem is that the average sentence has around 20 words!

One way to start writing in a less academic, more conversational way is to try writing like you talk. If actually writing like that is difficult for you, an easy way to get started is using a speech-to-text tool. That’s an accessibility function available on your computer but you can also just start a new email on a smartphone and dictate using Google or Siri. This will give you a good draft of your thoughts which you can edit and refine.

When writing, also be aware of the amount of jargon, acronyms, and technical terms you use. Are these terms your students will understand when they encounter them or are the terms things they are just learning? While some technical terms are necessary, take the time to spell out acronyms that your students may find unfamiliar and replace jargon with lay terms to both improve readability and set a more welcoming tone. If you are using Pressbooks, the glossary feature can be helpful when introducing new language.

Fonts

If you are creating your OER in Pressbooks, the font is generally set by your theme choice. If you are using the Malala theme, you have some font options for both text and headings. If you are creating a document in Word or Google Docs, you have a wide variety of font options.

Generally speaking, the clearer font is the more learning-friendly font. If students can’t decipher the words easily you can lose them whether or not the text is written at an appropriate reading level. Letters have to be quickly and clearly distinguishable from one another in order to read words and phrases easily and without having to stop to think about individual characters. Fonts that are very hard to read, like script-style fonts, can lead to both lack of comprehension and lack of motivation. For example, Song and Schwartz (2008) showed that students given either exercise instructions or recipes in an easy-to-read font believed that they would be able to complete the actions required and were more willing to try. Participants who were given the same instructions in a hard-to-read font understood less of the text and, as a result, thought the instructions were more complex, doubted they could do what was asked of them, and were less willing to even try.

The text also needs to be large enough to read. In Word or Google Docs that means 12 point fonts, not 10, so that the document can be read comfortably when printed. If a document contains footnotes or endnotes, the minimum font size for those should be 9 points. In a digital authoring space like Pressbooks or Canvas, there is no need to change the font size as readers can adjust the level of magnification in their browser settings.

Using Color

Using color to organize and call attention to things is a common strategy in textbooks and online learning materials. However, there are challenges to working with color due to differences in how different brands and types of devices display colors and how different people perceive colors as they are displayed.

The general rule is don’t use color alone to indicate something. Color-coding is a common practice in instructional materials but it ranges from being useless to being actively confusing for readers who are color blind. 1 in 12 men and 1 in 200 women are color blind. If you think about the size and composition of your classes, it’s very likely that you have color-blind students. When you consider creating and sharing an OER with the world, that number grows exponentially. Using color as an indicator is very prevalent in charts and diagrams so you need to make sure there is another way for your students to tell which line, bar, and pie slice are which.

If you are using highlighting or if you have text on a background color such as in a Pressbooks textbox, make sure that the color contrast is high enough that it can be read by low-vision and color-blind individuals. Tools such as the WCAG Contrast Checker tool can help you tell if your color contrast is good enough. If you are using Pressbooks, the Toptal Webpage Filter will let you check any public pages in your OER for the different types of color blindness. You can see the Creative Commons page of this book through the filter to see how the types of licensing chart looks (hint – it’s not good!) Please be aware that it does take a minute to load.

Links in Text

When creating any sort of digital text, you’ll probably want to link to other pages in the text or other websites. When you do, it’s important to use concise and meaningful link text. Having “naked URLs” like https://docs.google.com/document/d/16UXCfc1yswHPUut0CyRj20sT-mmanleE127obqoEvy8/edit?usp=sharing in your text doesn’t provide useful information about where the reader will be taken by clicking the link and it generally doesn’t look good. Instead, using meaningful text like “Measureable Outcomes Worksheet” describes the link destination. Also, if you use URLs, students using screen readers will have the entire link text read aloud to them twice.

When trying to avoid URLs, many people will use something like “click here” as the link text. For example, saying “Click here for the Measurable Learning Outcomes worksheet.” That’s also problematic for screen reader users as they can’t see where “here” is. Instead, saying “Go to the Measurable Outcomes Worksheet and (insert what you want the students to do with the worksheet).” provides a clear link with a description of what they will find and what they should do when they get there.

A Note on Media

If you are incorporating video into your OER, there are some additional considerations. All videos should have correct captions and all audio should have a correct transcript including any relevant non-speech audio. For more information on editing and requesting mechanical captions in Kaltura, please see the information on Accessible Videos in the Canvas Semester Checklist for IU East Instructors.

IU Resources

IU employees can use Siteimprove,a web-based tool that crawls websites and reports back on:

- quality assurance issues

- broken links and misspellings

- accessibility issues measured by the W3C Web Content and Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG).

IU also offers a free Canvas course on accessibility practices called, “7 Simple Steps for Creating More Inclusive Digital Content.” While geared towards IU employees and students, this course can be taken by anyone that signs up for a guest login. It is a self-paced course that takes about 2 hours to complete.

Contributors: Jeani Young, Sarah Hare, April Urban. IU resources added by Beth South.

If a student is using a screen-reader to read an etext, a Word or PDF document, or content in your Canvas site, the text needs to be formatted so that the screen-reader can process it properly. Screen readers are not like audiobooks. Please take a few minutes and listen to someone using a screen-reader to hear how very different of an experience it really is. The following video shows Mary Stores of IU's Assistive Technology & Accessibility Centers using a screen-reader to try to read parts of a Canvas site. (6:59)

Using Built-in Styles

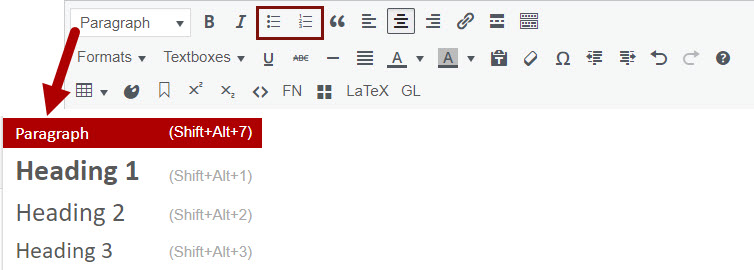

Headings are an important part of creating the visual hierarchy of your page or document. You can see on this page how larger headers are used to note different topics and slightly smaller headers separate subtopics within a section. Providing a visual hierarchy improves the usability of your materials by communicating the document structure. For a fuller description, see Visual Hierarchy: How Well Does Your Design Communicate? by Steven Bradley.

When adding headings to your OER (whether that's a Pressbook page, a Word doc, or a Google Doc) you need to format your headers using the built-in styles in the text editor (e.g., Heading 1, Heading 2, Heading 3) instead of just making text large and bold. All modern authoring tools offer different levels of headers that you can use to create an outline of your document to provide a visual hierarchy so that screen-readers can use it for navigation.

You'll also want to use built-in styles for bulleted lists and numbered lists instead of trying to create them using tabs or spaces. As Mary demonstrated in the video, these styles provide important information to a screen-reader. They also look a lot better, especially when your text wraps around to a second line.

Use Alternative Text for Images

Alternative text (commonly called "alt text") is invisible text attached to images. It is read aloud by a screen reader, enabling someone who can't see the image to hear what it is. You can add alt text in Pressbooks by clicking on an image and clicking the "edit" pencil icon. You can also add alt text in programs such as Microsoft Word and PowerPoint. See the resource list at the bottom of this page for instructions for a variety of programs.

Generally speaking, alt text shouldn't be much longer than 125 characters. If you need more than that, you may want to consider explaining some parts of the image in the surrounding text.

Alt text should never be the file name of the image.

To get you started writing alt text, here are some basic guidelines depending on the purpose of the image.

Active Images

- Active images serve as a link or button. Clicking it or hovering over it causes something to happen.

- Use alt text that conveys the function of the image (for example, "Go to the IUPUI Library website").

Informational Images

- Informational images convey information that is not given in a caption or the body of the content.

- Use alternative text that conveys the information you want the reader to get from the image (for example, "visualization of ocean temperatures off the Atlantic coast of the US showing an increase in temperature from north to south")

Decorative/Redundant Images

- The image is redundant to the text or conveys no information.

- The alt text field should be blank. While you can certainly add alt text saying "vase of yellow daffodils," it's not necessary if the image of the vase of daffodils is not providing information related to the rest of the content on the page.

Textual Images

- The image is of text.

- Use alternative text that is the same as the text in the image.

NOTE: If you have an image of text (like a screen capture of an article or book) where the text is longer than 125 characters, don't use the image. Type the text into your document so that it is readable to screen readers and so that students with low vision can enlarge the text as needed.

Avoid Using Tables Purely for Formatting

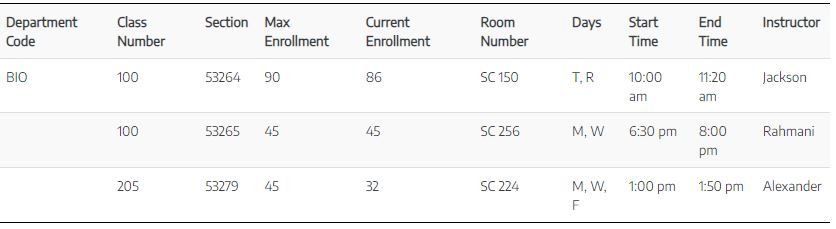

Tables are (mostly) for tabular data. The use of tables in etexts, documents, and in Canvas presents a special challenge for individuals using assistive technology. Screen readers read tables literally by column and row. For example, the following table used to format a class schedule

is read aloud by a screen reader like this:

|

|

Click the speaker icon to hear audio of the table being read aloud as a screen reader would. Note: This audio is slowed down significantly from a normal screen reader pace. |

Now, based only on the audio or the information in the gray box above, where is Dr. Rahmani's biology class located? See how difficult that is? Even though the top row looks like a header row, it wasn't set as such in Canvas so it's not telling you what column each item is in. This is especially unhelpful when everything shifts after row 2 because the first cells in rows 3 and 4 are left blank.

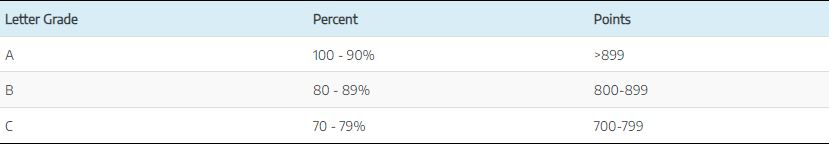

The following Grading Scale table has header rows set properly. You can't see a difference visually but you can hear it.

|

|

Click the speaker icon to hear audio of the table being read aloud as a screen reader would. Note: This audio is slowed down significantly from a normal screen reader pace. |

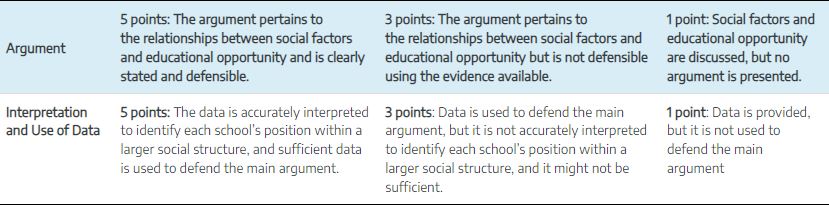

Using tables to organize information in columns and rows can be done if the information is written with accessibility in mind and if the table is formatted correctly. For example, a rubric in a table can be more or less accessible depending on how it is written. If you can read directly across any row and have it make sense then it is much more accessible than our class schedule option above. For example, the following rubric from Berkeley makes sense both when displayed in the table and when read aloud.

|

|

Click the speaker icon to hear audio of the table being read aloud as a screen reader would. Note: This audio is slowed down significantly from a normal screen reader pace. |

Resources for Accessible Documents

BC Campus Open Education Accessibility Toolkit

Creating an Accessible Syllabus using Microsoft Word by IU IT Training

PowerPoint Accessibility Tutorial from SUNY Oswego

Microsoft and Adobe How-to's

Contributors: Jeani Young, Sarah Hare, April Urban