5 Vegetable Oils, Information Asymmetry, and Unknown Unknowns

Zachary Todd

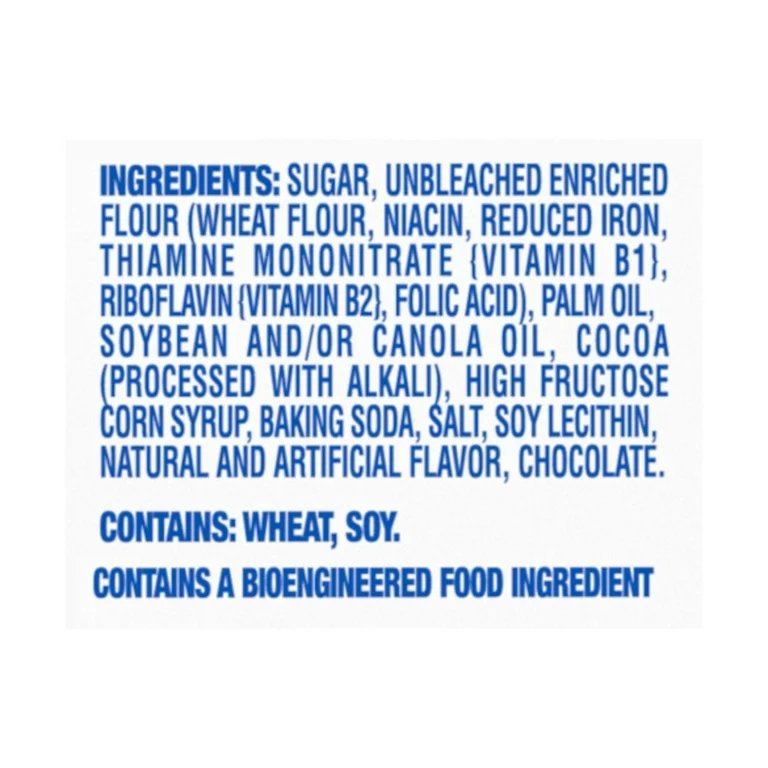

The automatic sliding doors of the grocery store open, and you step inside. Lining each aisle are the glossy packages of your favorite snack foods: Oreo cookies, potato chips, ice cream, granola bars, donuts, and candies. The packages seem to be calling your name. As if by magic, several packages end up in your cart. Who doesn’t love these snack foods? Oreo cookies, for example, contain high amounts of sugar and fat which hijack our brain’s reward system, making it a difficult challenge to only eat one. As you peruse the aisles you may peek at some of the ingredient lists. You will quickly notice that many of these processed foods share a handful of ingredients in common: canola oil, corn oil, sunflower oil, soybean oil, and cottonseed oil, (among others). You have just discovered the industrialized fats that allow many of our modern snack foods to exist. Over the course of this article, we will be examining and unveiling the largely unknown facts surrounding these ingredients.

Along with protein and carbohydrates, fat is an essential macronutrient that our bodies require as an energy source. Fat provides flavor and is a key ingredient in baking. Historically, bakers would have used fats such as butter or olive oil. Today, most food manufactures use industrialized fats such as vegetable oil to produce their foods. Vegetable oils have a long shelf life (lasting for years rather than months), and can also contribute to a food’s creaminess and “mouthfeel”. Not only this, but vegetable oils are much cheaper to produce, as they are generally created through a chemical process from seeds. In short, vegetable oils are a long-lasting, cheap, and delicious source of fat. They sound almost too good to be true.

Donald Rumsfeld, a former United Secretary of Defense, famously pointed out how the scariest aspects of life are the “unknown unknowns”, or the aspects of life “…we don’t know we don’t know”. While Rumsfeld statements specifically concerned terrorism and national defense, his words also ring true in other areas of life. For many consumers, there are several aspects about vegetable oils that are “unknown unknowns”. Not only do consumers not fully understand what vegetable oils are, they also do not even think to question whether they should consume vegetable oil on a regular basis. It turns out there are some very real concerns about the production and the consumption of industrialized fats such as vegetable oils. As we begin to better understand the history, production process, and prevalence of vegetable oils in particular, we may be challenged by the information we find.

Why are vegetable oils rarely questioned? The answer is found in the concept of “Information asymmetry”, an economic concept where one party participating in a transaction has more information than the other. Naturally, the party with more information will be at an advantage during the economic transaction. In this case, the companies behind our cheap and processed foods are able to pull a “veil” over our eyes as consumers. They leverage questionable manufacturing processes or ingredients that would appall most consumers were they to look behind the veil and understand how this food is produced. Since most consumers will never visit the factories where this food is made, they can continue living in ignorant bliss of the realities behind a food’s particular production process. As we seek to better educate ourselves as consumers, we will begin to pull back the veil carefully assembled by food manufacturers.

In order to begin disassembling this veil of information asymmetry, we must understand exactly how and why vegetable oil was invented in the first place. Author Pietra Rivoli describes some of this history in her book “The Travels of a T-Shirt in the Global Economy”. After separating out the desirable white lint from a particular raw cotton bundle, cotton farmers are left with thousands of pounds of excess cottonseed. While the unwanted cottonseed would have historically been thrown away, Procter and Gamble invented a brand new use for the material. They developed a new type of oil made from this cottonseed, and introduced a new product called CRISCO (standing for Crystalized Cottonseed Oil). CRISCO was first sold to consumers in 1911 (Rivoili). Rivoili describes cottonseed oil fairly optimistically, framing it as a way for farmers to avoid waste and earn extra money from their harvest in the process. Yet Rivoli does not elaborate on any of the obvious questions readers might have. Readers are left scratching their heads and asking “How exactly is cottonseed oil made?”

The snack food industry would prefer that we simply accept what is on our plates and chow down without stopping to question the exact processes used behind the scenes.

The snack food industry would prefer that we simply accept what is on our plates and chow down without stopping to question the exact processes used behind the scenes. However, a 2022 research paper by Said Gharby, entitled “Refining Vegetable Oils: Chemical and Physical Refining” reveals the complicated manufacturing process used behind the scenes to produce vegetable oil. Gharby describes how “Vegetable oils are obtained by mechanical expelling,” (Gharby, 2022) meaning seeds are crushed under high pressure with a machine. The resulting oil is naturally crude, meaning it is unpleasant to smell and taste. To remove the taste and smell, the oil is subject to harsh chemical processes in several stages during the refining process which include degumming, neutralization, washing/drying, bleaching, dewaxing, and deodorizing. The oil is repeatedly cooled and heated during these stages. The paper does admit there are drawbacks to the deodorization, stating “…deodorization…has other negative effects. Among them, the important bioactive molecules…may be removed in this step…Also, it sometimes generates other unwanted compounds such as 3-MCPD-esters” (Gharby, 2022). Reading this paper leaves readers with the impression that vegetable oils are more akin to a science experiment than a wholesome source of energy for our bodies.

Considering all these harsh chemical processes at work, it is natural to wonder if vegetable oils could lead to health problems in humans. Several months ago, I picked up a fascinating book called “The Genius Life” by health writer Max Lugavere. In the first chapter, Lugavere explains how most traditional fats (like olive oil and butter) have been replaced by vegetable oils. While these oils are usually marketed as a way to avoid saturated fat, Lugavere believes these claims are misleading. Such oils are not naturally occurring and harsh processing is required which “…allows a form of chemical damage called oxidation to occur, and this process progresses through to the storing, shipping, and cooking of these delicate oils” (Lugavere). Lugavere claims these oxidized oils lead to inflammation in the body, putting consumers at risk of chronic inflammation. Chronic inflammation, Lugavere warns, can lead to tumors and even cancer (Lugavere, 2020).

Lugavere is far from the only person worried about vegetable oil. At the beginning of her cookbook “Nourishing Traditions”, author Sally Fallon provides a section where she explains the confusion consumers have around fat. According to Fallon, fat (especially animal fat) has been presented as the enemy, as a result of the lipid hypothesis. The lipid hypothesis states that saturated fat and cholesterol consumption leads to heart disease. Since Americans eat much less saturated fat today, we would expect to see a decrease in heart disease, yet the prevalence of heart disease has risen since 1920 (Fallon, 2005). What could be the real culprit? Fallon suspects that both sugar and processed foods (filled with polyunsaturated fat) are to blame. While naturally occurring forms of fat (such as animal fat) are high in saturated fat, industrialized forms of fat are high in polyunsaturated fat. While our bodies do need small quantities of polyunsaturated fat from food, our current highly processed diet overwhelms our body with more polyunsaturated fat than our bodies can process. Polyunsaturated fat is far less stable when compared with its saturated and monounsaturated counterparts, and tends to become rancid or oxidized when exposed to heat during the production process. The rancid oil contains free radicals: “atoms with an unpaired electron in an outer orbit”. These free radicals go on to damage our red blood cells and DNA/RNA strands, wreaking havoc throughout the body (Fallon, 2005). Fallon concludes that the type of processed fat we eat is the true cause behind increased heart disease, and she suggests that consumers not shy away from increasing animal fat consumption which has too often been villainized.

Had my family and I better understood the implications of what we were putting in our bodies, we may have made different decisions about what to eat: either eliminating or greatly reducing certain foods from our diet.

Whether or not we buy these claims about the danger of vegetable oil, we must be cautious about the information asymmetry surrounding this topic. Since their inception in 1911, vegetable oils have not been widely understood by most consumers, and it is only because of health writers like Lugavere and Fallon that these concerns have slowly begun to enter the public sphere of discussion. Like most kids, I grew up eating fairly well, but not without my fair share of Pringles, Cheetos, and Goldfish (all of which contain copious amounts of vegetable oil). Had my family and I better understood the implications of what we were putting in our bodies, we may have made different decisions about what to eat: either eliminating or greatly reducing certain foods from our diet.

To determine the ubiquity of vegetable oils, I decided to research which foods in my diet contain vegetable oils. I made a list of some of the processed foods I eat on a semiregular basis, and carefully examined the list of ingredients on each. First off, Clancy’s potato chips from Aldi. The first ingredient, of course, was potatoes, but the second was vegetable oil. Since ingredients on packages are listed by descending weight, we know that vegetable oil is a crucial ingredient to produce these potato chips. On many packages, I noticed another worrying trend. After the “Vegetable Oil” listing, I would often see “Contains One or More of the Following: Corn, Sunflower, Safflower, or Canola Oil”. Presumably, each batch contains a different type of vegetable oil depending on which type is cheaply and readily available. This adds further unknown unknowns, as the consumer does not even know exactly which type of oil they are putting in their body. Vegetable oil was the second ingredient in both Kroger corn chips and Goldfish, and the first ingredient in Newman’s Own salad dressing. Finally, I expected to find vegetable oil hiding in Clif Bars, but it turns out that Clif Bars do not contain vegetable oil, which is consistent with the company’s commitment to prioritize organic ingredients. Regardless, Clif Bars proved to be the exception, not the rule. It’s clear that vegetable oils are lurking in a majority of processed foods we purchase and consume today.

I’m not interested in resolving the debate around vegetable oil. I’m certainly not a nutritionist or dietitian, and it’s not my job to tell people what they can or can’t eat. While enrolled at the LAMP (Liberal Arts and Management Program) here at IU, my classmates and I have learned the LAMP motto by heart: “One perspective is never enough”. The problem here, however, is there is largely only one perspective on vegetable oils: a perspective of unawareness. When asked about vegetable oils in their food, few consumers understand exactly what they are, how they are made, or which foods contain them. It seems only fair that consumers should better understand how vegetable oil is made, especially when it is too often the first or second item on an ingredient list.

As consumers, it is easy to feel powerless in the face of large and powerful food corporations. What practical first steps can we take as consumers? How can we vote with our wallets and ensure that more healthy and wholesome sources of fat are being used to produce our foods? A practical first step would be to make a habit of reading the ingredients on packages, and becoming aware of which ingredients may be harmful. Once you are aware of which ingredients are used in which foods, you will be able to make more educated choices about which foods to purchase.

While ingredient awareness is an important first step, it cannot solve the entire problem. Most consumers work under time and budgetary constraints, meaning it is not always reasonable to expect consumers to spend their limited time researching and purchasing food items that are free from vegetable oils. Food corporations are unlikely to change the ingredients they use without external pressures, so greater government regulation around food may be necessary. Increased regulations could require packages to be more clear about the industrialized fats used. Additionally, companies could create alternate products with cleaner ingredients and let consumers decide which to purchase. Further research is needed to determine if consumers would be willing to accept this price/ingredient trade-off.

Some people believe that vegetable oils are a harmless innovation that can ultimately serve to democratize access to cheap and delicious snacks for everyone. Others believe that consumption of vegetable oil puts the public at risk for chronic inflammation, and may lead to further health consequences that are not yet fully understood. I believe we are only beginning to understand the true health consequences of consuming vegetable oils on a regular basis. Regardless, I only argue that we should work to bring both sides of the argument into the public sphere and let consumers vote with their voices and wallets. Currently, I believe most consumers today are not given the necessary information to make informed choices about what they put in their bodies. We are what we eat, which is why this particular type of information asymmetry seems especially wrong from a moral perspective. While there will still continue to be unknowns about the safety of industrialized fat sources, I remain optimistic that more time, research, and public awareness may help them graduate from an “unknown unknown”, to a “known unknown”.

References

Fallon, S., Enig, M. G., Murray, K., & Dearth, M. (2005). Nourishing traditions : the cookbook that challenges politically correct nutrition and the diet dictocrats. Newtrends Publishing, Inc.

Gharby, S. (2022). Refining Vegetable Oils: Chemical and Physical Refining. The Scientific World Journal, 2022, e6627013. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/6627013

Lugavere, M. (2020). The Genius Life. HarperCollins.