Introduction

Welcome आपका स्वागत है!

Whether you have some background in Hindi (or a related language) or are just beginning your study, this book is here to serve as both a reference guide and a complete, asynchronous self-study course in the Devanāgarī script. The book has been designed to move step by step in a maximally approachable way, with a variety of exercises to check your comprehension and practice as you go. Mastering Devanāgarī will give you greater access to the rich heritage and culture of South Asia as well as deepening your understanding of the everyday reality of hundreds of millions of its users. We hope that this book will be a steady and reliable companion as you take your first steps into Devanāgarī and further on into the study of South Asia.

About Devanāgarī: The script and its sounds

The Devanāgarī (देवनागरी, sometimes referred to simply as नागरी Nāgarī) script is the primary writing system for Hindi and dozens of other languages, including Bhojpuri, Braj Bhasha, Dogri, Hindi, Maithili, Marathi, Nepali, Pali, Sanskrit, and many other languages and language varieties across South Asia. Primarily found in India and Nepal today, it is one of the Brahmic script family which spreads all the way from Central Asia to Sri Lanka to Southeast Asia. With hundreds of millions of users across South Asia and beyond, it ranks among the most widely used scripts in the world. Devanāgarī in its contemporary form emerged roughly 1100 years ago in North India, initially serving primarily for Hindu and Jain religious and scholarly texts. The language we now know as Hindi—the lingua franca of much of North India—had developed from Śaurasenī Prakrit by about the 10th century. However, this language went by many names, including Urdu, Hindi, Hindustani, Hindvi, Rekhta, and Khari Boli. In fact, the term “Hindi” itself is simply the Persian word for “Indian,” and was used to differentiate indigenous South Asian vernaculars from Persian, the language of power throughout much of North India at the time.

Until the 19th century, this Hindi was largely written in the Perso-Arabic script. The shift toward Devanāgarī began when British colonial sociology sought to separate and codify Hindi and Urdu as distinct languages, each with its own script (Devanāgarī and Perso-Arabic respectively) and communal identity (Hindu and Muslim). Political movements throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries strengthened this differentiation, leading to wider adoption of Devanāgarī in literature and government. From the 19th century onward, Devanāgarī became increasingly associated with what we now call Hindi. However, the communal associations of these scripts are far more complex and nuanced than the simple binary of Hindi-Devanāgarī-Hindu versus Urdu-Nastaliq-Muslim would suggest. These associations have only become widely accepted fairly recently. This history is discussed in more detail in Part 7, and learners of Hindi and Urdu would benefit from reviewing this history, and key texts are listed in the Further Reading section at the end of this introduction.

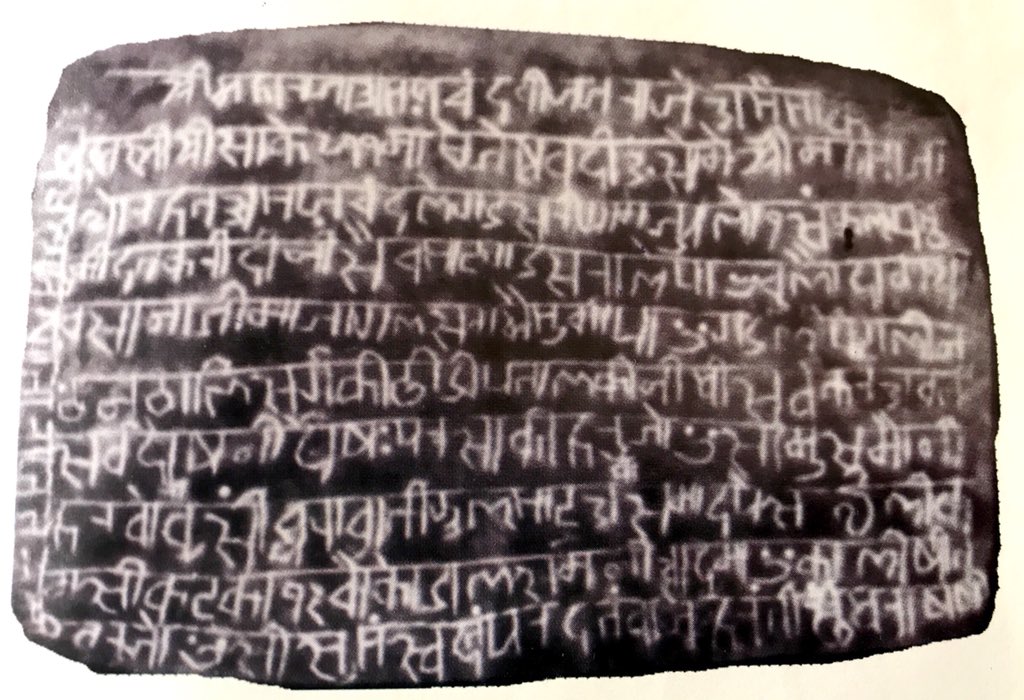

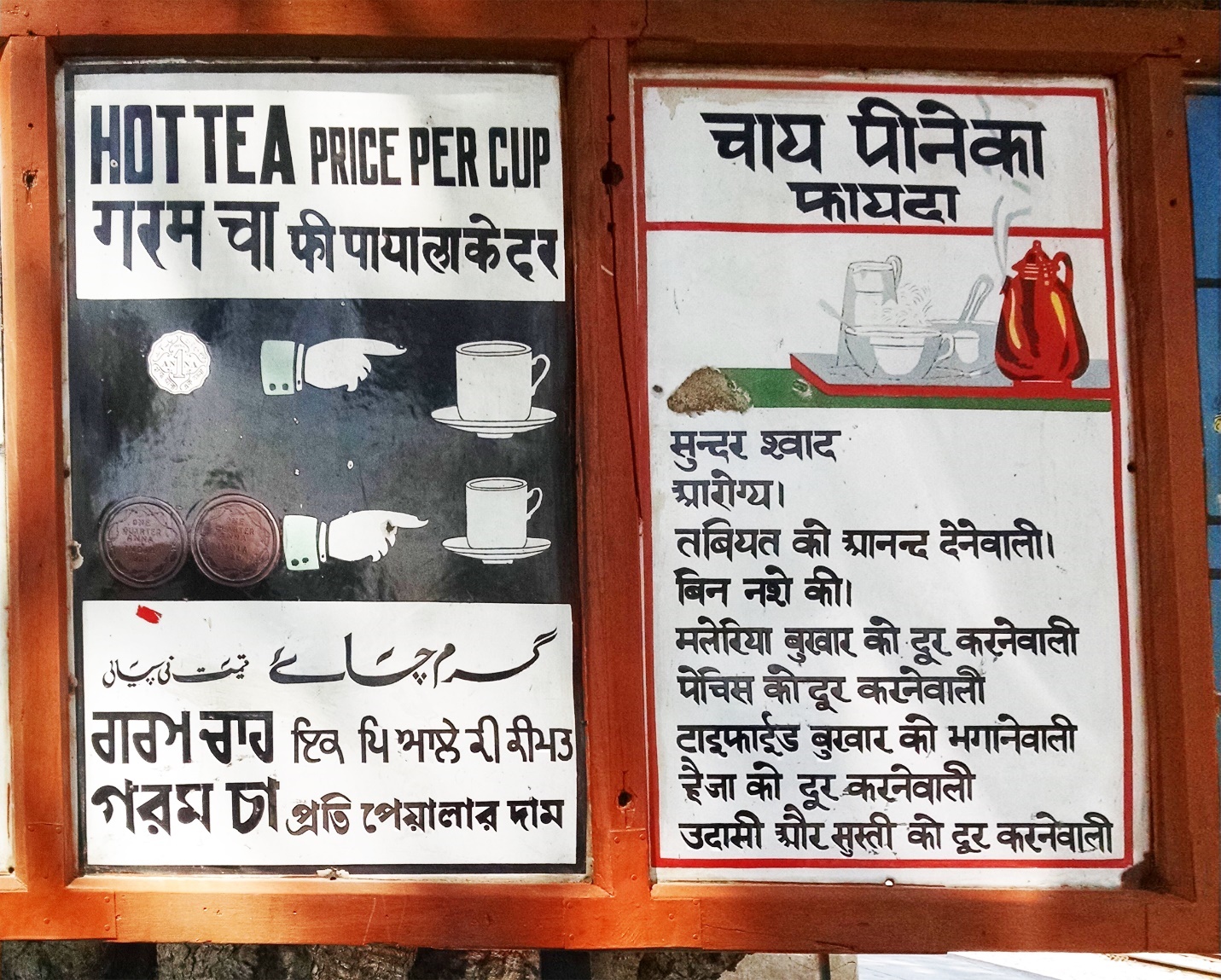

Devanāgarī is type of script known as an abugida and has 52 basic characters (अक्षर akṣar). In an alphabet such as English, the base unit of writing is a single, unchanging letter. In an abugida the base unit is a syllable, and vowels are appended to consonants using diacritic-like markings. This type of system is also distinct from abjads such as Arabic or Hebrew where vowel marking may be only optional. Devanāgarī, unlike English, is precisely phonetic and extremely regular, with a one-to-one correspondence of sounds and characters. Below are some historical images of the script. More authentic images, including contemporary, real-life examples in a variety of typefaces, will also be found throughout the textbook.

Pronunciation: some key aspects for learners

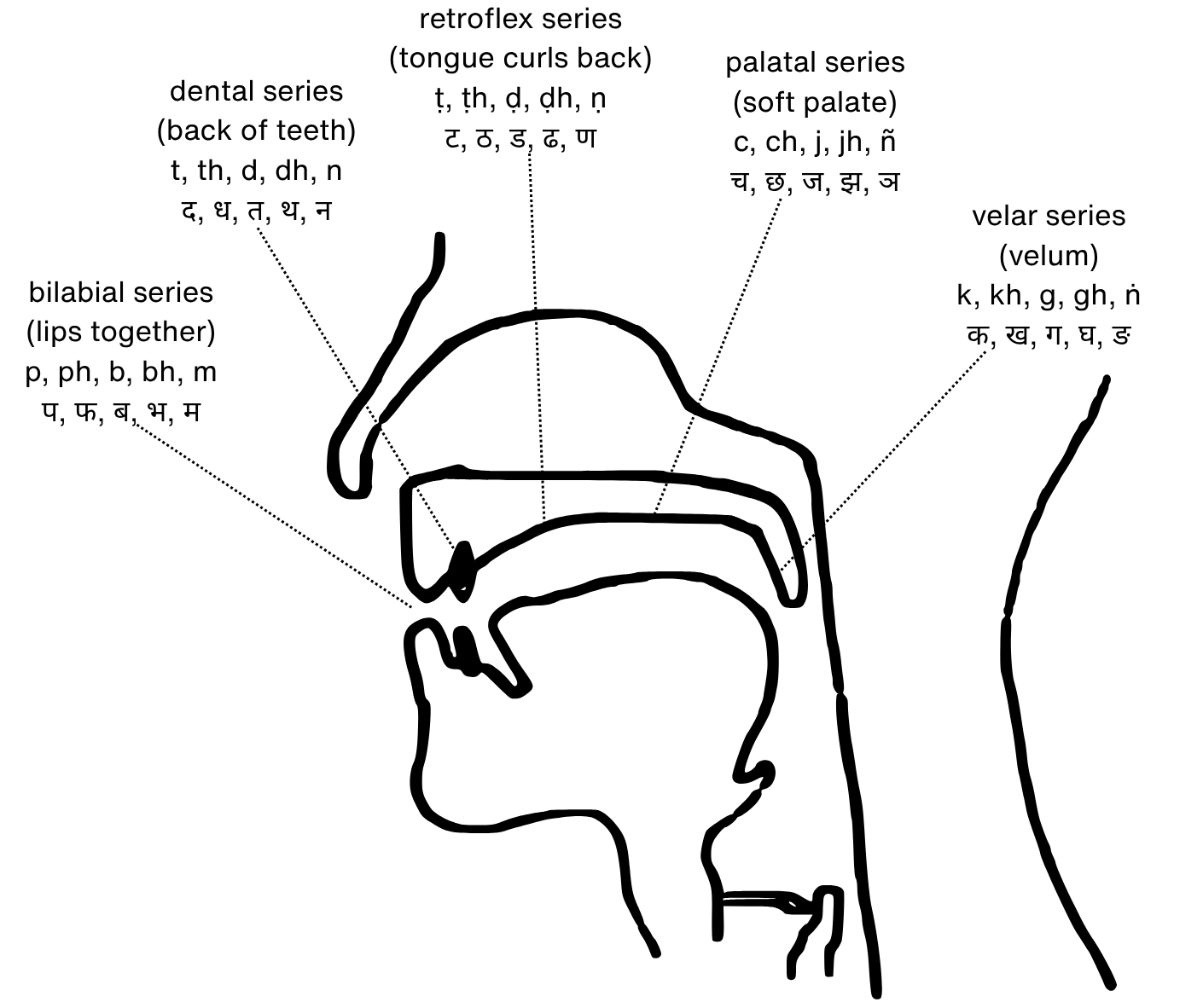

Devanāgarī is systematically arranged according to the point and manner of articulation of its letters. More simply, what this means is that sounds are grouped based on where they are made in the vocal tract, and how they are made. The plosive consonants (or ‘stops,’ where the air is briefly but completely obstructed), are organized into further organized based on whether they are voiceless or voiced (that is, whether the vocal cords are vibrating during sound production) and whether they are aspirated (also known as murmured) or not. An aspirated consonant is usually represented in Roman script with an h, and represents a breathily-voiced consonant, followed by an audible puff of air. The chart below (Image 4) illustrates these groupings based on the anatomy of the vocal tract.

Monolingual English speakers often struggle with two distinctive features of the Hindi sound system: voicing combined with aspiration, and the contrast between dental and retroflex sounds. Because most standard varieties of English lack these features, learners may need time to recognize and produce them accurately. This textbook will discuss the pronunciation of each character of Devanāgarī as it teaches the written forms, but some readers may benefit from understanding the broader sound system beforehand, including the concepts of voicing and aspiration and the points of articulation. While perfect pronunciation or technical linguistic knowledge aren’t essential for learning the script, developing a basic grasp of how these sounds function provides a foundation for understanding the organization of the writing system as well as the sounds.

Voicing refers to the vibration of the vocal folds during speech. When these folds vibrate, the sound is voiced (as in “z”), and when they do not, it is voiceless (as in “s”). You can feel this by placing your hand on your throat and alternating between a prolonged “ssss” and “zzzz”—the vibrating or buzzing sensation you feel during “z” is voicing in action.

Aspiration, on the other hand, is a burst of air that follows the articulation of certain sounds. In linguistics such sounds are also called murmured or breathy. English exhibits aspiration in a limited way, primarily on voiceless stops like “p,” “t,” and “k” at the start of stressed syllables when followed by a vowel. For example, compare the words “key” and “ski”: both use the sound “k,” but the former is aspirated, while the latter is not. Try holding your hand in front of your mouth while pronouncing both to feel the breathy difference. You can even practice holding a piece of paper in front of your mouth and trying to make it move with an aspirated sound or remain still with an unaspirated sound.[1]

Monolingual English speakers often remain unaware of differences in aspiration, perceiving aspirated and unaspirated versions of a sound as identical. Swapping them might sound slightly unusual to such speakers but typically won’t alter the meaning of a word. In contrast, Hindi and many Indo-Aryan languages treat aspirated and unaspirated sounds as distinct phonemes—that is, changing them alters meaning. For instance, को ko is a grammatical particle that marks an object or recipient, while खो kho is the stem of a verb meaning “to lose.” Similarly, पल pal means “moment”, while फल phal means fruit.

Therefore, where English distinguishes only between voiced and voiceless sounds at each place of articulation (e.g., the first sounds in “cap” and “gap”), Hindi makes a four-way distinction by considering the presence or absence of both voicing and aspiration. This layered contrast is reflected in the structure of the Devanāgarī alphabet, where each group also includes a corresponding nasal consonant. The chart below, which shows the stops in their standard alphabetical order, illustrates this organization.

|

|

voiceless unaspirated |

voiceless aspirated |

voiced unaspirated |

voiced aspirated |

nasal |

|

velar |

क k |

ख kh |

ग g |

घ gh |

ङ ṅ |

|

retroflex |

ट ṭ |

ठ ṭh |

ड ḍ |

ढ ḍh |

ण ṇ |

|

palatal |

च c |

छ ch |

ज j |

झ jh |

ञ ñ |

|

dental |

त t |

थ th |

द d |

ध dh |

न n |

|

bilabial |

प p |

फ ph |

ब b |

भ bh |

म m |

Another key difference in the sound systems of English and Hindi is the retroflex and dental series of sounds. In most varieties of English, t and d are articulated at the point in the mouth known as the alveolar ridge, which you can feel with your tongue just behind your teeth. Hindi, like many other South Asian language, does not articulate sounds at this ridge but instead has a series of consonants pronounced with the tip of the tongue on the teeth (dental) and a series of consonants produced with the tip of the tongue flipping backwards to make contact with the top of the mouth (retroflex). Hindi speakers generally perceive English t and d as retroflex, not dental, meaning that in Devanāgarī retroflex characters ट ṭ and ड ḍ are used to represent English t and d. At the same time, English speakers often struggle to hear these as different sounds at all. However, with time and practice learners can overcome this challenge.

About this book

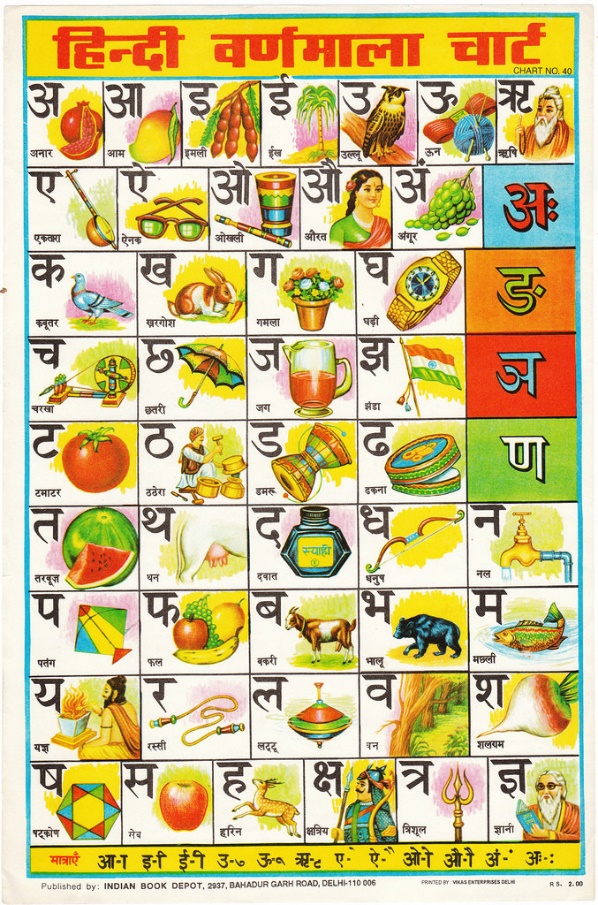

This text is not organized fully according to the traditional Devanāgarī varṇmālā or alphabetic order, which you can see in an example of a traditional schoolroom poster in Image 5. The traditional order begins with all vowels, then progresses systematically through all consonants according to their place and manner of articulation. Because we take a student-centered, proficiency-based approach to reading and writing, this text has somewhat modified this order by gradually introducing vowels with different sets of consonants. The script is thus broken into 10 chapters, keeping the main groupings of consonants as in the traditional order but introducing vowels as well as other specific topics, such as ways of combining consonants, in a more gradual way. As a fully digital textbook, audiovisual elements also accompany each lesson, including videos showing how to form each letter and sound samples for pronunciation. To help you evaluate your progress, microfeedback exercises for self-assessment are included at the end of each chapter, as well as practice worksheets.

To avoid confusion among learners, it is important to use a regular system of transliteration in order to accurately represent the sounds of Hindi with a one to one ratio. In this text, we have used the ISO 15919 system of transliteration, as it is one of the most widely used systems for rendering South Asian languages in Roman script.1 However, while it is provided for convenience in the early stages of learning, you are encouraged to focus on the script itself rather than its transliteration. Transliteration can often become a crutch that will impede a student’s progress in the actual script; additionally, it can be misleading to students not familiar with how Indic sound systems differ from English. Therefore, students would do well to avoid “crutch” practices such as writing out the transliterations below each Hindi word. These do seem helpful in the short term, but in fact they prevent the learner from directly connecting the Devanāgarī shapes to their corresponding sounds without a Roman intermediary, and make the process of script acquisition much slower in the long run.

In addition to the ISO transliteration, the IPA (International Phonetic Alphabet) symbol for each sound is also included when a new letter is introduced. The IPA symbols link to the Wikipedia pages for those sounds and learners are encouraged to explore them further, especially any they find challenging. However, while this book uses some technical linguistic terms and specialized symbols (such as IPA), these should be taken simply as an aid to learning, rather than something to learn in and of itself—that is, ignore these if they aren’t helpful to you!

Learning Outcomes

Some users of this book may be fluent speakers who have grown up outside of India and thus not had the opportunity to be introduced to the script in school. Some users of this book may be familiar with closely-related languages, and some users of this book may be absolute beginners who have little or no exposure to Indian languages. Regardless of your prior proficiency in Hindi, working through this book will provide you with the basic building blocks of literacy in the Devanāgarī script. You will not only learn the shapes of each letter and the sounds they represent, but also how to combine them. You should be able to correctly sound out almost any word you come across written in Devanāgarī, even an unfamiliar one, and similarly you should be able to render any word more or less faithfully in the script. Additionally, you will learn from real-world examples how letters appear in a variety of typefaces and contexts and practice identifying letters and sounding out words from these authentic images.

Further Reading

To learn more about Hindi and Devanāgarī we recommend the following resources. You may need to use your IU login to access some online resources, but open resources have been shared wherever available.

History of Devanagari

Bright, William. 1995. “Section 31. The Devanāgarī Script.” In The World’s Writing Systems, edited by Peter T. Daniels and William Bright, 384-390. New York, Oxford University Press.

Gnanadesikan, Amalia E. 2021. “Brahmi’s Children: Variation and Stability in a Script Family.” Written Language & Literacy 24(2):303-35. doi:10.1075/wll.00057.gna.

India. Central Hindi Directorate. 1967. Devanāgarī through the Ages. [New Delhi].

Malli, Karthik. 2022. “Research into the History of the Printed Form of Devanagari.” Typotheque, March 21. https://www.typotheque.com/research/devanagari-the-makings-of-a-national-character.

Miller, Christopher Ray. 2013. Devanagari’s descendants in North and South India, Indonesia and the Philippines. Writing Systems Research. doi:10.1080/17586801.2013.857288

Pandey, Krishna Kumar, and Smita Jha. 2019. “Tracing the Identity and Ascertaining the Nature of Brahmi-Derived Devanāgarī Script.” Acta Linguistica Asiatica 9(1):59-73. doi:10.4312/ala.9.1.59-73.

Ross, Fiona. 2021. Invisible hands: tracing the origins and development of the Linotype Devanāgarī digital fonts. Journal of the Printing Historical Society 3(2):111-153.

Singh, A. K. (Arvind Kumar). 1991. Development of Nāgarī Script. Delhi, Parimal Publications.

Language, politics, and Hindi

Ahmad, Rizwan. 2008. “Scripting a New Identity: The Battle for Devanāgarī in Nineteenth Century India.” Journal of Pragmatics 40(7):1163-83. doi:10.1016/j.pragma.2007.06.005.

Ahmad, Rizwan. 2011. “Urdu in Devanāgarī: Shifting Orthographic Practices and Muslim Identity in Delhi.” Language in Society 40(3):259-84. doi:10.1017/S0047404511000182.

Hakala, Walter. 2016. Negotiating languages: Urdu, Hindi, and the definition of modern South Asia. New York: Columbia University Press.

King, Christopher Rolland. 1994. One Language, Two Scripts: The Hindi Movement In Nineteenth Century North India. Bombay: Oxford University Press.

Orsini, Francesca. 2002. The Hindi Public Sphere 1920-1940: Language and Literature In the Age of Nationalism. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Orsini, Francesca, and Ravikant. 2022. Hinglish Live: Language Mixing Across Media. Hyderabad: Orient Blackswan.

Stark, Ulrike. 2019. “Letters Beautiful and Harmful: Print, Education, and the Issue of Script in Colonial North India.” Paedagogica Historica 55(6):829-53. doi:10.1080/00309230.2019.1631860.

McGregor, Stuart. 2003. “The Progress of Hindi, Part 1: The Development of a Transregional Idiom.” In Literary Cultures in History: Reconstructions from South Asia edited by Sheldon Pollock, 912-957. Berkeley: University of California Press. doi:10.1525/9780520926738-021

Rahman, Tariq. 2011. From Hindi to Urdu: A Social and Political History. Karachi: Oxford University Press.

Trivedi, Harish. 2003. “17. The Progress of Hindi, Part 2: Hindi and the Nation” In Literary Cultures in History: Reconstructions from South Asia edited by Sheldon Pollock, 958-1022. Berkeley: University of California Press. doi:10.1525/9780520926738-022.

General resources for Hindi language and grammar

Agnihotri, Rama Kant. 2022. Hindi: An Essential Grammar. Oxford: Routledge.

Everaert, Christine. 2017. Essential Hindi Grammar: With Examples From Modern Hindi Literature. Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press.

Kachru, Yamuna. 2014. Hindi. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Co.

Knapczyk, Kusum, and Peter Knapczyk. 2020. Reading Hindi: Novice to Intermediate. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

Wikipedia. 2007. “Hindustani Phonology.” Last modified July 21, 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hindustani_phonology.

- To learn more about how this works in English, see Anderson, Catherine. 2018. "3.4 Aspiration in English," Essentials of Linguistics. eCampusOntario/McMaster University. https://pressbooks.pub/essentialsoflinguistics/chapter/3-5-aspirated-stops-in-english/ ↵