In this chapter, we’ll look at the problems and opportunities afforded by social media in relationship with truths and knowledge.

6

Julie Feighery

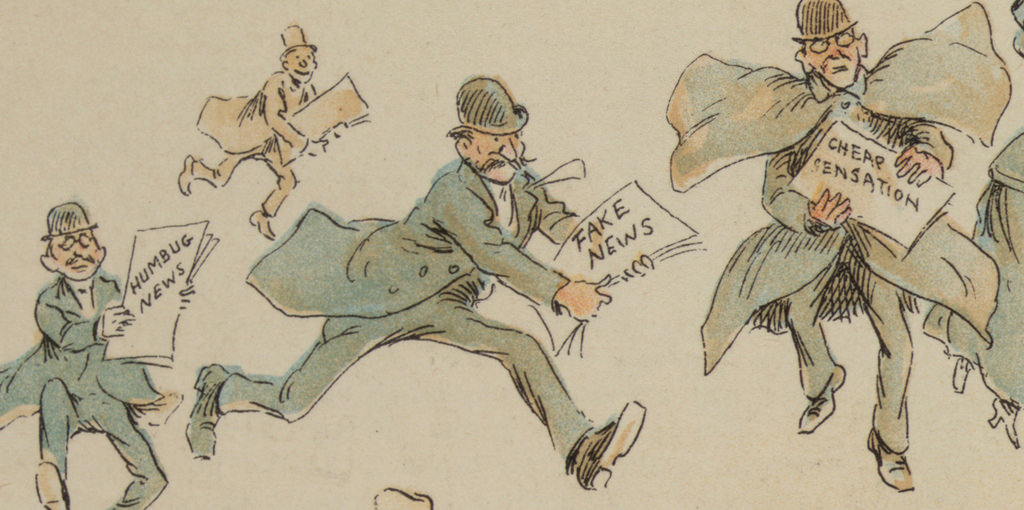

“Fake news” and “post-truth”

Much has been made in recent years of fake news. This is a term that circulates ubiquitously through social as well as traditional media. In 2016, Oxford Dictionaries presented “post-truth” as its “word of the year.” But what do these terms mean, and what do they have to do with social media?

To understand these terms, we have to look closely at what we expect with the word “news” and notions of truth and “fake”-ness. These conversations start with the concepts of objectivity and subjectivity.

Objectivity and subjectivity

To be objective is to present a truth in a way that would also be true for anyone anywhere; so that truth exists regardless of anyone’s perspective. The popular notion of what is true is often based on this expectation of objective truth.

The expectation of objective truth makes sense in some situations – related to physics and mathematics, for example. However, humans’ presentations of both current and historic events have always been subjective – that is, one or more subjects with a point of view have presented the events as they see or remember them. When subjective accounts disagree, journalists and historians face a tricky process of figuring out why the accounts disagree, and piecing together what the evidence is beneath subjective accounts, to learn what is true.

Multiple truths = knowledge production

In US society, we have not historically thought about knowledge as being a negotiation among multiple truths. Even at the beginning of the 21st century, the production of knowledge was considered the domain of those privileged with the highest education – usually from the most powerful sectors of society. For example, when I was growing up, the Encyclopedia Britannica was the authority I looked to for general information about everything. I did not know who the authors were, but I trusted they were experts.

Enter Wikipedia, the online encyclopedia, and everything changed.

Captioned version of history of Wikipedia video.

The first version of Wikipedia was founded on a more similar model to the Encyclopedia Britannica than it is now. It was called Nupedia, and only experts were invited to contribute. But then one of the co-founders, Jimmy Wales, decided to try a new model of knowledge production based on the concept of collective intelligence, written about by Pierre Lévy. The belief underpinning collective intelligence, and Wikipedia, is that no one knows everything, but everyone knows something. Everyone was invited to contribute to Wikipedia. And everyone still is.

When many different perspectives are involved, there can be multiple and even conflicting truths around the same topic. And there can be intense competition to put forth some preferred version of events. But the more perspectives you see, the more knowledge you have about the topic in general. The results of a negotiation between multiple truths can be surprisingly accurate. A 2012 study by Oxford University comparing the accuracy levels of Wikipedia to other online encyclopedias found Wikipedia had higher accuracy than Encyclopedia Brittanica.

What are truths?

So what qualifies as “a truth?” Well, truths are created and sustained from three ingredients. The first two ingredients are evidence and sincerity. That is, truths must involve evidence – pieces of information that could or can be seen or otherwise experienced in the world. And truths must involve sincerity – the intention of their creator to be honest.

And the third ingredient of a truth? That is you, the human reader. As an interpreter, and sometimes sharer/spreader of online information and “news”, you must keep an active mind. You are catching up with that truth in real-time. Is it true, based on evidence available to you from your perspective? Even if it once seemed true, has evidence recently emerged that reveals it to not be true? Many truths are not true forever; as we learn more, what once seemed true is often revealed to not be true.

Truths are not always profitable, so they compete with a lot of other types of content online. As a steward of the world of online information, you have to work to keep truths in circulation.

Why people spread “fake news” and bad information

“Fake news” has multiple meanings in our culture today. When politicians and online discussants refer to stories as fake news, they are often referring to news that does not match their perspective. But there are news stories generated today that are better described as “fake” – based on no evidence.

“Fake news” has multiple meanings in our culture today. When politicians and online discussants refer to stories as fake news, they are often referring to news that does not match their perspective. But there are news stories generated today that are better described as “fake” – based on no evidence.

So why is “fake news” more of an issue today than it was at some points in the past?

Well, historically “news” has long been the presentation of information on current events in our world. In past eras of traditional media, a much smaller number of people published news content. There were codes of ethics associated with journalism, such as the Journalist’s Creed, written by Walter Williams in 1914. Not all journalists followed this or any other code of ethics, but in the past, those who behaved unethically were often called out by their colleagues and unemployable with trusted news organizations.

Today, thanks to Web 2.0 and social media sites, nearly anyone can create and widely circulate stories branded as news; the case study of a story by Eric Tucker in this New York Times lesson plan is a good example. And the huge mass of “news” stories that results involves stories created based on a variety of motivations. This is why Oxford Dictionaries made the term post-truth their word of the year for 2016.

People or agencies may spread stories as news online to:

- spread truth

- influence others

- generate profit

Multiple motivations may drive someone to create or spread a story not based on evidence. But when spreading truth is not one of the story creators’ concerns, you could justifiably call that story “fake news.” I try not to use that term these days though; it’s too loaded with politics. I prefer to call “news” unconcerned with truth by its more scientific name…

BS!

Think I’m bsing you when I say bs is the scientific name for fake news? Well, I’m not. There are information scientists and philosophers who study different types of bad information, and here are some of the basic overviews of their classifications for bad information:

- misinformation = inaccurate information; often spread without intention to deceive

- disinformation = information intended to deceive

- bs = information spread without concern for whether or not it’s true

Bugs in the human belief system

We believe bullshit, fake news, and other types of deceptive information based on numerous interconnected human behaviors. Forbes presented an article in 2017, Why Your Brain May Be Wired To Believe Fake News, which broke down a few of these with the help of the neuroscientist Daniel Levitin. Levitin cited two well-researched human tendencies that draw us to swallow certain types of information while ignoring others.

- One tendency is belief perseverance: You want to keep believing what you already believe, treasuring a preexisting belief like Gollum treasures the ring in Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings series.

- The other tendency is confirmation bias: the brain runs through the text of something to select the pieces of it that confirm what you think is already true, while knocking away and ignoring the pieces that don’t confirm what you believe. We’ll be reading more about confirmation bias in the next chapter.

These tendencies to believe what we want to hear and see are exacerbated by social network-enabled filter bubbles (which we will look at next week) When we get our news through social media, we are less likely to see opposing points of view, which social networking sites filter out, and which we are unlikely to see on our own.

Tips for “reading” social media news stories:

- Put aside your biases. Recognize and put aside your belief perseverance and your confirmation bias. You may want a story to be true or untrue, but you probably don’t want to be fooled by it.

- Read the story’s words AND its pictures. What are they saying? What are they NOT saying?

- Read the story’s history AND its sources. Who / where is this coming from? What else has come from there and from them?

- Read the story’s audience AND its conversations. Who is this source speaking to, and who is sharing and speaking back? How might they be doing so in coded ways? (Here‘s an example to make you think about images and audience, whether or not you agree with Filipovic’s interpretation.)

- Before you share, consider fact-checking. Reliable fact-checking sites at the time of this writing include:

That said – no one fact-checking site is perfect.; neither is any one news site. All are subjective and liable to be taken over by partisan interests or trolls.

Fake Images and Videos

Technology and AI (which we will be discussing at the end of the semester) have made it easier for images and video to be faked. Jevin West and Carl Bergstrom at the University of Washington have created a “Which Face is Real” site, which describes some tells for fake images. The following video from PBS program Above the Noise has additional useful information about fake images and how to detect them:

read the transcript for Can you tell a video is fake?

Sources

Fake News is modified from Humans R Social Media – 2024 “Living Book” Edition Copyright © 2024 by Diana Daly is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Fake Images and Videos. by IU South Bend Libraries is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

s21_095_p3meme © John Westphal is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

quality_bullshit © Doug Beckers is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

FakeNews_PublicDomainReview_Flickr © The Public Domain Review is licensed under a Public Domain license

Fake Images by IU South Bend Libraries is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

“Can You Tell when an Image is Fake?” YouTube, Uploaded by Above the Noise, 5 June 2019.