Section 1: Information on Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)

1 Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) Quick Information Sheet

According to criteria outlined in the current version of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5; APA, 2013), autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is now a single diagnosis that replaces the four disorders of Autistic Disorder (i.e., autism), Asperger’s Disorder, Pervasive Developmental Disorder-Not Otherwise Specified (PDD-NOS), and Childhood Disintegrative Disorder.

Under past criteria (4th ed., text rev.; DSM-IV-TR, APA, 2000), the above noted disorders as well as Rett’s Syndrome were included within a broader category named Pervasive Developmental Disorders (PDDs). However, often referred to as autism spectrum disorders by lay people, the medical terminology of PDD and the disorders noted within this classification, were later replaced with the single reference to autism spectrum disorder (ASD) in the current medical classification. Despite this change, professionals, families and others may still refer to PDD and the related disorders noted above in that individuals previously diagnosed will retain their diagnosis and it will take some time for the field to fully transition from one set of diagnostic criteria to a new one.

Individuals with ASD have challenges related to social communication and interaction as well as restricted, repetitive behaviors, interests or activities, including potential for hyper or hyposensitivity to sensory input.

What causes ASD?

- Currently, there does not appear to be one specific cause for ASD. It is likely that both genetics and environment play a role.

- Genes appear to play a role as siblings of individuals with ASD are more likely to have ASD than are other people (Ruzich et al., 2017)

- Many studies have found abnormal levels of neurotransmitters as well as differences in several areas of the brain for individuals with ASD (Drenthen et al., 2016,; Mohammad-Rezazadeh, Frohlich et al., 2016; Schumann et al., 2010 ).

- ASD is NOT caused by parental practices or anything you did or did not do as parents or that your parents did or did not do (Neely-Barnes et al., 2011).

- ASD is known to be a neurodevelopmental disorder that primarily affects higher cognitive functions, including social skills, communication, and behavior (DSM-5; APA, 2013)

What can be done for individuals with ASD?

- There are many intervention options. These may include educational treatments, behavioral interventions, therapies (e.g. speech, occupational), and/or medication. A comprehensive evaluation will identify which interventions are most needed based on individual needs.

- Any intervention chosen should be adapted to meet individual needs and their continued monitoring of is essential to ensure they are meeting such individual needs.

- Most professionals agree that the earlier the intervention the better. However, intervention even as an adult will be of benefit (targeting quality of life and pertaining to the inclusion goals integral at that time) in that there is the ability to learn and improve across a lifetime.

- There is NO known cure for ASD. Be very cautious of anyone who offers you a cure for your child.

How common is ASD?

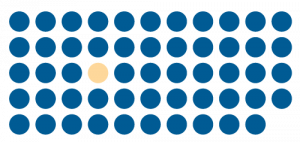

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), current estimates indicate an average of 1 in 54 children in the United States have ASD (CDC, 2020)

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), current estimates indicate an average of 1 in 54 children in the United States have ASD (CDC, 2020)- Estimates of ASD across the lifespan continue to be updated as diagnostic tools and our knowledge of co-occurring medical issues continue to improve (Klaiman et al., 2014).

- ASD occurs in individuals of all races, ethnicities, social classes, and educational backgrounds (CDC, 2020 Nevison& Zahorodny, 2019).

- ASD is approximately four times more common in males than females (CDC, 2020), but it is possible that females are underdiagnosed (Dean et al., 2017)

- ASD is among the broader category of “disabilities” affecting approximately 15% of the population thus comprising the nation’s largest minority group (CDC, 2018)

- ASD is a lifelong neurodevelopment disorder thus impacting individuals across the lifespan and/or with potential to be diagnosed into adulthood (Courchesne, Campbell, & Solso, 2011)

- ASD co-occurs with many psychiatric or neurodevelopmental disorders and is often associated with a range of frequent co-occuring medical problems (van Timmeren et al., 2017)

- Unemployment rates for individuals with ASD are approximately 65% reflecting a rate four times greater than the under/unemployment rate of individuals with disabilities and more than 15-20 times the unemployment rate of peers (approximate range of 3-4%; Gerhardt, Cicero, Mayville, 2014; U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2018) despite an estimated 60-70% having a desire to work in a competitive employment setting, a key social determinant of health (Newman et al., 2009 as listed at Autism Now, 2013)

Who can provide a diagnosis of ASD?

- Psychiatrists, developmental pediatricians, pediatric neurologists, and psychologists with expertise in childhood onset disorders and ASD typically provide a medical diagnosis.

- Pediatricians and family physicians follow practice guidelines for screening and referral (Hyman et al., 2020).

- Other disciplines (e.g., therapists, social workers) may screen and suggest further referral for ASD evaluation.

How is ASD diagnosed?

- There is no medical or biological test for ASD.

- Screenings are completed to detect early signs of ASD.

- If screenings or symptoms suggest the presence of ASD, a comprehensive evaluation by a multidisciplinary team is recommended.

- A comprehensive evaluation may include, but not be limited to, a review of developmental, social, and family history, observations of behavior, hearing, and vision testing, genetic testing, and/or assessments of speech/language, cognitive ability (IQ), adaptive behavior, motor and sensory abilities, and achievement skills.

- A medical diagnosis of ASD is made according to diagnostic criteria as described in the current version of the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5; APA, 2013). Medical diagnosis may be made by physicians and licensed psychologists following a comprehensive evaluation.

- Within the school setting, a child may be eligible for special education services under ASD eligibility if the child meets diagnostic criteria for ASD as outlined within the current edition of the DSM (DSM-5; APA, 2013) and if such symptoms or challenges result in a consistent and negative impact upon the child’s academic achievement and/or functioning performance (IDOE-Title 511- Article 7, 2010). Special education eligibility is determined through a multidisciplinary evaluation and is a case conference committee decision.

- It is important to note that a medical diagnosis of ASD is not equivalent to a special education eligibility of ASD and vice versa.

DSM-IV-TR: Overview

For your reference, we have included information pertaining to the diagnostic criteria contained within the previous edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV-TR; APA, 2000) given that some of these disorders and language will still be present during the time of transition to the use of new terminology.

Under the previous classification, a broad umbrella category known as Pervasive Developmental Disorder (PDDs) included the following diagnoses:

- Autistic Disorder (commonly referred to as autism)

- Asperger’s Disorder

- Pervasive Developmental Disorder, Not Otherwise Specified (PDD-NOS)

- Childhood Disintegrative Disorder

- Rett’s Disorder

As specified within the diagnostic criteria (DSM-IV-TR; APA, 2000), these disorders generally shared overlap with core challenges relating to the areas of communication, social interaction, and restricted repetitive and stereotyped patterns of behavior, interests, and/ or activities. However, over time, the PDDs with most overlap were more commonly referred to as autism spectrum disorders (ASDs) by lay people and this language was later adopted within the medical field with ASD becoming a singular diagnosis and category within the updated DSM 5 (APA, 2013).

Early symptoms or signs of core challenges were often noted by age three though individuals may not present to specialists or diagnosed by this time. In addition, for some, delays and unusual behaviors could even be noted earlier, in infancy or as a toddler. For others, early development may appear to be on track until around 18 -24 months when a regression or loss of skills might appear to occur (usually in language or social skills). Still others may appear to show little to no change in their development; instead of losings skills, they appear to halt progression.

What were the primary changes made between DSM-IV-TR and DSM-5?

- ASD is now a single diagnosis encompassing characteristics previously associated across four diagnoses (Autistic Disorder, Asperger’s Disorder, Pervasive Developmental Disorder-Not Otherwise Specified [PDD-NOS] and Childhood Disintegrative Disorder).

- ASD falls within the category of neurodevelopmental (or brain development) disorders given the growing body of research surrounding early signs, development, and associated factors.

- DSM-5 considers the range of ages for which the effect of ASD symptoms may manifest. Symptoms of ASD must appear within the early developmental period but may not become entirely apparent until situations and demands exceed the individual’s social skills and capacities.

- The areas of functioning affected for individuals with ASD went from 3 to 2 areas including (1) challenges related to social communication and social interaction, and (2) restricted repetitive behaviors, interests, or activities.

- Sensory sensitivities or unusual interest in sensory aspects of the environment are now included in the domain of repetitive behaviors, interests, or activities, thus broadening our understanding of that affected area.

- Within DSM-5, a rating of the level of support needed by the individual with ASD was added to reflect the severity of ASD symptoms.

- Social (Pragmatic) Communication Disorder was added within DSM-5 to describe individuals who have trouble with social skills but do not have restricted or repetitive behaviors, interests, or activities.

- The new criterion has more in common with that of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10, WHO, 2004), which helps medical doctors understand many disorders and diseases.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed.-text revision). Washington, DC: Author.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

Blumberg, S. J., Bramlett, M. D., Kogan, M. D., Schieve, L. A., Jones, J. R., & Lu, M. C. (2013). Changes in prevalence of parent-reported autism spectrum disorder in school-aged US children: 2007 to 2011– 2012. National Health Statistics Reports, 65, 1-11.

Indiana Special Education Rules: Title 511, Article 7, Rules 32-47 (December 2010).

World Health Organization. (2004). ICD-10: International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems. World Health Organization.