5 Russian “Fromagicide”

By Melanie Reinhart

Even everyday items, such as cheese, have their place in illicit economies. In 2014, the United States and the European Union imposed economic sanctions on Russia due to its annexation of Crimea in Ukraine [2]. Russia responded by imposing bans on food imports, including cheese, from many Western nations. While local cheese production increased by 30 percent to compensate, residents reported that foreign cheese imports were impossible to replace [3]. This caused the illegal cheese trade to spread. Banned products were publicly destroyed to deter future smuggling efforts. In a country suffering from inflation and a rising poverty rate, the waste of food outraged many people [4]. As evidenced by the black-market cheese trade, demand for any product, no matter how inessential, will generally outweigh any laws or regulations against it.

Before 2014, there was no need for illegal cheese smuggling in Russia. At this point, like all other refrigerator staples, cheese was widely available without restriction. This changed after the 2014 Russian annexation of Crimea, the peninsula on Ukraine’s southern border [5]. Ukraine previously gained independence from the Soviet Union after its collapse in 1991. Then in 2000, Russia signed a deal with the European Union reaffirming Ukraine’s independence, including the Crimean Peninsula. On March 16, 2014, a referendum followed Russian military buildup in the peninsula, in which Crimean citizens voted to leave Ukraine and join Russia [6]. While the referendum ballot questions were edited multiple times, the option to retain the current state of Crimea was left out, giving voters the option only to “support reunifying Crimea with Russia” or “support the restoration of the 1992 Crimean constitution and the status of Crimea as a part of Ukraine.” This wording was vague and did not clarify whether this would restore the original version of the constitution that declared Crimea an independent state, or the amended version where Crimea was declared an autonomous republic with Ukraine [17]. The referendum gave no option for voters who wanted current constitutional arrangements to remain unchanged, as they were only asked whether they would support joining Russia or have greater Ukrainian autonomy [7]. The referendum vote went against many international agreements where Russia had pledged to uphold the Ukrainian sovereignty instead of get involved in reclaiming Crimea [7]. President Vladimir Putin defended the decision to annex Crimea, as the referendum’s results appeared to support Crimea’s annexation [6].

The UN General Assembly, many world leaders, including Ukraine, rejected the vote as a breach of their agreements because it was an illegal “referendum at gunpoint [8]”. The vote was preceded by illegal Russian invasion of Crimea, and protesters and Ukrainian military and families experienced wide-spread intimidation, in the form of threats and kidnappings [17]. While the referendum results showed that 96.8 % of voters supported joining Russia, the vote was carried out with Russian military stationed at polling locations, putting threatening pressure on voters to cast their ballots in Russia’s favor [19]. The EU, US, Canada and other Allies retaliated against the invasion and occupation of Crimea by imposing sanctions on Russia [9]. These sanctions restrict access to Western financial markets and placed embargoes on Russian exports [9]. In response to the Western sanctions, Russia’s president, Vladimir Putin, signed a decree on August 6, 2014, banning certain food imports from the European Union, United States, Canada, Norway, and Australia [10]. While private individuals would still retain rights to bring back small food quantities for personal use, the ban encompassed any products intended for commercial use [11].

The availability of local products or the restrictions against their imports did not diminish demand for foreign cheeses. Many Russians felt that local cheese quality did not compare to banned foreign goods. Tatiana, who manages an international company in Moscow, reported that Russian cheese tastes like “modeling clay,” and like many others, she prefers foreign cheeses [12]. To fulfill the ever-present demand for imported cheese, smugglers began obscuring the origin of shipments to suggest the products entered legally [1]. Products were often repackaged in neighboring countries, and shipments traveling to Russia would unload imported cargo secretly, so that illegal cheese imports could remain undocumented [12].

Russian citizens were still allowed to order limited amounts of cheese and banned food products in foreign online shops for personal use [12]. One man, Matevosyan, used this as a business opportunity [12]. This practice is technically legal, as the online shop is located in Germany, outside of the ban’s jurisdiction [12]. Matevosyan’s shop sells cheese produced by small farms in Germany, France, Italy, Britain and the Netherlands [12]. In order to stay within ban regulations, the shop only sells cheese in small quantities [12]. It also hired a detective agency to ensure Russians are not abusing its website and selling commercially [12].

While some people like Matevosyan legally used the bans to their advantage, some individuals attempted to ignore regulations entirely. Russians can legally bring five kilograms of cheese back into Russia for personal use under the ban, yet some individuals attempt to circumvent the limit [14]. One man attempted to enter Russia from Poland [3]. He was stopped at the Russian border near Kaliningrad with nearly 1000 pounds of illegal cheese in his vehicle [13]. While the man claimed to be transporting the goods for personal use, the customs officers were not fooled [13]. Another man was caught by officials attempting to cross into Russia from Finland [14]. His nervous demeanor led to a full search of his Volkswagen Caravelle, which revealed 67 wheels of illicit cheese stuffed into the side compartments of the man’s car doors, amounting to about 220 pounds of smuggled Western cheese.14 Border control guards confiscated both his cheese and car [14].

The black market cheese trade exists on more than just an individual level. Police and security services have methodically searched warehouses near Moscow up to this point, as they were aware that people were circumventing the bans by smuggling contraband products [20]. Both the decreased supply of cheese in Russia and the unwavering demand for foreign cheese imports create an optimal opportunity for individuals to involve themselves in black market activity. In August of 2015, Russian officials busted the largest criminal “cheese ring” to date. [15]. Officials arrested six individuals in possession of 470 tons of smuggled cheese through a joint raid of four law enforcement agencies [15]. They located 17 different addresses where they uncovered cheese production and labeling equipment [20]. Since starting their operation, the uncovered international criminal group supplied over $20 million worth of illicit cheeses to Moscow and St. Petersburg shops [10]. Those involved faced up to a decade in prison for fraud conviction [10].

The smugglers involved in the cheese ring do more than just import banned cheese. They also import food products required to produce their own counterfeit cheese. In the 2015 case, officials confiscated large amounts of banned western rennet, which contains enzymes required for cheese production [3]. In addition, they identified forged labels from foreign cheese producers that were not permitted in Russia following the ban [3]. They uncovered that the group was reorganizing and relabeling the cheese products at warehouses, appearing as though they were the leading banned brands [15]. In this way, Russians began “buying cheese the same way people bought weed in 1980s Brooklyn…corner stores have become black market cheese dealers [3].” Essentially, Russian customers buy locally made cheeses made from illegally imported cheese products, believing it is an expensive European good.

While cheese imports were officially banned, many foreign brands continue appearing in Russian storefronts [11]. Up to this point, authorities have tried several methods of deterring banned cheese trade. They shut down websites and filed lawsuits against those involved in the illegal trade, and they also set up a hotline for citizens to report their neighbors who they suspected of involvement in the cheese trade [3]. As illegal food smuggling attempts persisted, Vladimir Putin ordered customs officials to do more than turn away contraband cheese products at the Russian border. A new policy was created that required any confiscated food products to be publicly destroyed, in an act now known as “fromagicide [3].” Over 26,000 tons of products were destroyed due to these restrictions, being bulldozed and dumped in landfills [5]. Pictured in Figure 1, a bulldozer in Belgorod, Russia publicly destroys contraband cheese and plows it into a landfill, aiming to deter smuggling efforts [1]. Putin required contraband cheese destruction “in front of witnesses” and demanded the act was recorded to “preclude corruption [4].”

Additionally, the waste of food has outraged many Russian citizens. In a country where 23 million live in poverty, bulldozing cheese solely based on its origins seems incomprehensible [11]. Enraged by the waste, over 500,000 Russians have signed a petition on Change.org requesting that the government donate confiscated food to those in need, rather than pointlessly and wastefully destroying it [1,3]. While 68 percent of Russians support banning Western food products, about half opposed the government’s orders to destroy confiscated foods [11]. While many Russians support the import ban, they widely criticize the methods of enforcement. Rather than supply landfills, contraband foods could support local orphanages and homeless shelters. Dmitry Peskov, Putin’s spokesman, notified the public that the President would investigate the petition [21]. Yet, Putin ultimately took a stance against the petition, suggesting that banned foods entered Russia without required certificates, and were potential health risks [21].

Following the implementation of the bans, authorities initiated inspections and raids on Russian food retailers [16]. The authorities required retailers to provide reports showing their remaining stock of banned produce legally obtained before the ban and their plan on dispersing it [16]. Further inspection raids are conducted to ensure that the remaining supplies of now-banned cheeses were not illegally restocked [16]. To compensate for the decrease of incoming supply, local businesses increased cheese production by roughly 30 percent [3]. Even with this increased yield, food prices rose by 20.7 percent in the first year following import bans [11].

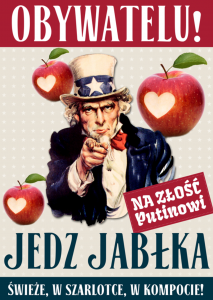

Economies that relied on trade with Russia experienced setbacks following the food import bans. For example, Poland previously depended on billion-dollar fruit exports to Russia that were cut off after the import bans were announced [5]. As a result, Polish apple farmers and sellers lost essential revenue from Russia [5]. In response, many Poles pledged to increase their consumption of apples to support their country’s economy and spite Putin’s new import policies [5]. This response turned into a social media movement, where people would post pictures of themselves consuming apples with the hashtag “#jedzablka (“eat apples”) [5].” Posters like the one pictured in Figure 2 sprang up on social media, urging individuals to increase apple consumption “to annoy Putin.” Even with an increase in apple consumption, the ban was projected to cost 0.6 percent of Poland’s GDP by the end of the year, according to the Polish Deputy Prime Minister [5].

The illicit trade of cheese in Russia highlights the connections and contributions ordinary people have to black market activity. People interact with the black market even in purchasing something as common as cheese products, which were smuggled across the Russian border and relabeled for sale. Whether or not a good is legal, the demand remains, and black-market activity rises to fulfill the demand. To deter illicit economies, Russia publicly demonstrated the consequences of involvement by circulating videos of contraband cheese destruction. As President Putin has annually extended the import bans, most recently on June 24, 2019, cheese imports will continue to be banned through 2020 [18]. Despite the extensive efforts of the Russian government to end illegal activity, the Russian cheese trade continues.

[1] Kramer, Andrew E. “Russia Destroys Piles of Banned Western Food.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 6 Aug. 2015. www.nytimes.com/2015/08/07/world/europe/russia-destroys-piles-of-banned-western-food.html

[2] “U.S. Sanctions on Russia: An Overview.” Congressional Research Service, 2019. fas.org/sgp/crs/row/IF10779.pdf

[3] Maza, Cristina. “Amid Accusations of ‘Fromagicide,’ Russia Busts Criminal Cheese Ring.” The Christian Science Monitor, The Christian Science Monitor, 19 Aug. 2015.www.csmonitor.com/Business/2015/0819/Amid-accusations-of-fromagicide-Russia-busts-criminal-cheese-ring

[4] Chappell, Bill. “We Will Bury You: Russia Bulldozes Tons Of European Cheese, Other Banned Food.” NPR, NPR, 6 Aug. 2015. https://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2015/08/06/430043765/we-will-bury-you-russia-bulldozes-tons-of-european-cheese-other-banned-food

[5] Sharkov, Damien. “Russia Has Destroyed 26 Tons of Western Cheese and Fruit.” Newsweek, Newsweek, 7 Aug. 2018. www.newsweek.com/russia-has-destroyed-26-tons-food-because-kremlin-ban-1060297

[6] Isachenkov, Vladimir. “Putin Marks 5th Anniversary of Russia’s Annexation of Crimea.” PBS, Public Broadcasting Service, 18 Mar. 2019. www.pbs.org/newshour/world/putin-marks-5th-anniversary-of-russias-annexation-of-crimea

[7] Pifer, Steven. “Five Years after Crimea’s Illegal Annexation, the Issue Is No Closer to Resolution.” Brookings, Brookings, 18 Mar. 2019. www.brookings.edu/blog/order-from-chaos/2019/03/18/five-years-after-crimeas-illegal-annexation-the-issue-is-no-closer-to-resolution/

[8] Morris, Chris. “Crimea Referendum: Voters ‘Back Russia Union’.” BBC News, BBC, 16 Mar. www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-26606097

[9] Christie, Edward. “Sanctions after Crimea: Have They Worked?” NATO Review, 2015. www.nato.int/docu/review/2015/Russia/sanctions-after-crimea-have-they-worked/EN/index.htm

[10] Oliphant, Roland. “Russian Police Bust ‘International Cheese Smugglers’.” The Telegraph, Telegraph Media Group, 18 Aug. 2015.

www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/europe/russia/11809733/Russian-police-bust-international-cheese-smugglers.html

[11] Mendeleyeev. “Russia Buries the Cheese: Observations on the Latest Food Ban.” The Mendeleyev Journal – Live From Moscow, 18 Aug. 2015. russianreport.wordpress.com/2015/08/18/russia-buries-the-cheese-observations-on-the-latest-food-ban/

[12] Kiselyova, Maria. “Russian Cheese Lovers Find Way Round Import Ban.” Reuters, Thomson Reuters, 7 Apr. 2016. www.reuters.com/article/us-russia-sanctions-food/russian-cheese-lovers-find-way-round-import-ban-idUSKCN0X40SC

[13] Stupina, Yekaterina. “Beating the Border Guards: 5 Classic Contraband Cases from Russia.” Russia Beyond, 24 July 2015.

www.rbth.com/society/2015/07/24/beating_the_border_guards_5_classic_contraband_cases_from_russia_47995.html

[14] Smith, Adam. “Smuggler Caught at Russian Border with 100kg of Illicit Cheese.” Metro, Metro.co.uk, 10 Aug. 2017. metro.co.uk/2017/08/10/smuggler-caught-at-russian-border-with-100kg-of-illicit-cheese-6843761/

[15] Eremenko, Alexey. “470 Tons of Smuggled Cheese Seized in Moscow, Russian Police Say.” NBCNews.com, NBCUniversal News Group, 19 Aug. 2015. www.nbcnews.com/news/world/470-tons-smuggled-cheese-seized-moscow-russian-police-say-n412226

[16] Oliphant, Roland. “Russian Authorities Crackdown on Western Food Imports.” The Telegraph, Telegraph Media Group, 13 Aug. 2014.www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/europe/russia/11031281/Russian-authorities-crackdown-on-Western-food-imports.html

[17] Clegg, Veronika. “Referendum at Gun Point and the Crisis in Ukraine: Beyond the Propaganda.” E-International Relations, 2014, www.e-ir.info/2014/03/18/referendum-at-gun-point-and-the-crisis-in-ukraine-beyond-the-propaganda/

[18] “Russia – Prohibited & Restricted Imports Russia – Prohibited Imports.” Russia – Prohibited & Restricted Imports, 2019, www.export.gov/article?id=Russia-Prohibited-Restricted-Imports

[19] Smith, Alexander. “Disputed Crimea Referendum Sees 96.8 Percent Vote to Join Russia.” NBCNews.com, NBC Universal News Group, 11 June 2015,www.nbcnews.com/storyline/ukraine-crisis/disputed-crimea-referendum-sees-96-8-percent-vote-join-russia-n54326

[20] Walker, Shaun. “Russia Swoops on Gang Importing £19m of Banned Cheese from Abroad.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 18 Aug. 2015,www.theguardian.com/world/2015/aug/18/russia-cheese-ban-gang-uncovered-arrests-moscow

[21] Baczynska, Gabriela. “Russian ‘Food Crematoria’ Provoke Outrage amid Crisis, Famine Memories.” Reuters, Thomson Reuters, 6 Aug. 2015, www.reuters.com/article/us-russia-crisis-food-idUSKCN0QB1CE20150806

[22] Rainsford, Sarah. “Russians Shocked as Banned Western Food Destroyed.” BBC News, BBC, 7 Aug. 2015, www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-33818186.

[23] “Jedz Jablka Na Zlosc Putinowi.” Facebook, www.facebook.com/1516781721887496/photos/a.1516785608553774/1551410191757982/?type=3&theater.