The Black Market Behind Adoption in Modern America

By Anna Hsiao

Today, adoption is a considerably well-established method to provide children in need with loving homes and to start a family. However, in the early 1900s, adoptable children were considered greatly undesirable and parents were advised to completely avoid adoption by child welfare professionals. During the 1920s, one woman worked to reshape America’s perception of adoption as a whole. She spoke at conferences in all major American cities, advised First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt on matters of adoption, and was invited to Harry Truman’s presidential inauguration (Raymond, 2007). But unbeknownst to most, the woman widely recognized for destigmatizing adoption was also busy kidnapping, abusing, and selling children. Her name was Georgia Tann and for over 30 years, she and an elaborate network of co-conspirators took advantage of the lack of regulation around adoption to create a mass-marketable scheme that shipped as many as 5,000 babies to all forty-eight states and Great Britain, with some paying more than $100,000 per child in today’s dollars (Raymond, 2007). Tann’s methodologies, sculpted by eugenic prejudices, the exploitation of poor families, and the commercialization of children made her a millionaire and became the framework for modern America’s adoption practices and legislation.

Despite having passed the first modern adoption law in the United States in 1851, adoption remained rare throughout the nineteenth century (Bussiere, 1998). Many families refused to consider adoption due to the stigma against unmarried mothers and “illegitimate” children; those that adopted were usually motivated by labor and profit as opposed to any altruistic intents (Noll-Wilensky, 2019). However, the rise of the industrial revolution brought forth increased mechanization and a series of child labor laws, eventually leading to the demise of unskilled child labour (Holt, 1999). This prompted a shift in American’s views on adoption and of children in general; now, less emphasis was placed on a child’s earning potential, and the American public began placing more weight on their sentimental value (Holt, 1999).

As the prospect of adoption became more attractive, the American eugenics movement simultaneously took root in the early 1900s. Advocates, basing their arguments on Mendel’s theory of genetic inheritance, believed that undesirable traits, such as mental illness and poverty, were hereditary. Influenced by her involvement in the movement, Tann polarized the poor and the wealthy, arguing that low-income parents were incapable of proper parenting. She aimed to save poor, white children from their “lowly” parents by placing them with people of “high type” (Wingate & Christie, 2019). Tann, the child of a powerful judge, began her career by implementing her philosophies in the Mississippi Children’s Home Society. Her eugenics-driven beliefs developed “both her business and the institution of adoption by doing something unprecedented: making homeless children acceptable, even irresistible, to childless couples” (Raymond, 2007). She spun the narrative by insisting that these children were neither “of sin nor genetically flawed” (Noll-Wilensky, 2019). Rather, they were untainted and could be molded into whatever the adoptive parents wished them to be. When she was terminated for her questionable child-placing practices, Tann took her beliefs and now-refined methods to Tennessee, where her father’s connections were able to get her the job at the Memphis branch of the Tennessee Children’s Home Society. In 1924, Tann began trafficking children.

Tann took advantage of the lack of regulation around adoption to perpetuate her scheme. She targeted state hospitals, prisons, and homes for unwed mothers, with “scouts” looking for children that would be “better off” with her– particularly, good looking, healthy, white children with blonde hair and blue eyes (Wingate, 2017). Single parents were frequently exploited during times of desperation with offers of temporary accommodation for their children, only to be told that welfare officers had taken their children away. Her favorite scheme was to drive through low-income neighborhoods, picking out the prettiest children and offering them rides in her shiny luxury car. Children were taken from their yards, daycares, and churches, and once they were in, they usually never saw their families again. Tann falsified birth certificates to make children more appealing and documented the children as years younger to make them more challenging to find (Celeste, 2019).

The demand for adoptable infants rose, especially among busy, successful women, with the declined birth rates of white Americans and the popularization of baby formula. Between 1850 and 1915, the annual birth rate for white Americans dropped nearly 40 percent (Raymond, 2007). This “shortage” of white children helped Tann sell the idea that each child was precious, even those born to unworthy parents. To keep up with this new, profitable promotion, Tann would pay nurses and doctors at maternity hospitals to help her. Some mothers were told their newborns died and would be asked to sign their death certificate, only to be signing away their parental rights. Other mothers who just gave birth and under sedation were asked to sign “routine papers,” which unbeknownst to them were legal documents placing their children up for adoption (Wingate, 2017). “Tann preyed on women’s desperation, their poverty, and their sense of shame. If they were not sedated and tried to hold on to the babies after birth, Tann would step in and say, ‘Well, you don’t want people in your home town to know about [your pregnancy], do you?’” Robert Taylor, an investigator, said in a 1992 interview with “60 Minutes” (Celeste, 2019).

Part of Tann’s success can be attributed to her clientele– she sold to anyone and everyone, silencing those who got in her way. She often sold to those who would otherwise be rejected by normal adoption channels, so long as they could pay for it. Her frequenters included single men suspected to be pedophiles who would adopt young girls from the Children’s Home Society (Harrington, 2020). But Tann’s most popular consumer base was the rich and famous; the high-profile list included political machines such as New York Governor Herbert Lehman and celebrities Dick Powell and Joan Crawford (Wingate, 2017). Their support not only helped her to popularize the idea of adoption, but legislators were now more inclined to support laws favourable to her operation (Austin, 1992). Her reach extended to all corners of the United States, though the most popular destinations resided with states that did not require adoption records, such as New York and California. Assisted by the Memphis Police Department, she was able to transport the children from Tennessee to anywhere she wanted without raising suspicion (Harrington, 2020). If the parents, biological or adoptive, asked too many questions, Tann would threaten to have them arrested or the child removed.

Her cruelty extended to her treatment of the children; physical, emotional, and sexual abuse was a common occurrence at the Tennessee Children’s Home Society. Children with congenital disabilities or “too ugly” or “old” to be of use would be left in the sun or starved. Tann’s former employees revealed that babies were kept in sweltering conditions with some drugged until they were sold to keep them quiet. If that was not enough, children were also “hung in dark closets, beaten, or put on starvation rations for weeks at a time” (Celeste, 2019). One adoptee, who was five when she was kidnapped, once said “sexual abuse at the hands of Georgia Tann was… presented as your favor.” “I keep trying to block it all out, but it keeps coming,” she continued (Celeste, 2019). Memphis had the highest U.S infant mortality rate in the 1930s as a result of Tann’s scam (Harrington, 2020).

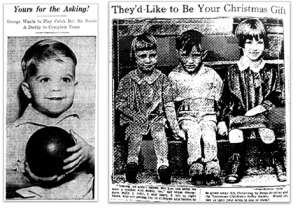

Tann not only popularized adoption, she commercialized it. “Baby catalogs” were created to help to-be-parents choose their perfect child. Provocative ads featuring the kidnapped children, such as “Yours for the Asking” and “They’d Like to be Your Christmas Gift,” could be found in newspapers all over America. One of Tann’s most infamous publicity stunt involved the raffling of 20 to 30 babies off every Christmas in her ‘Christmas Baby Give Away’ (Wingate, 2019). For $25 (~$350 today), clients could purchase as many raffle tickets as they desired; Tann pocketed thousands, giving away only a fraction of her “merchandise” in the process. Despite Tennessee law requiring an adoption fee of $7 (~ $75 today) for in-state children, Tann sold each child for $1,000 each, $10,000 today (Celeste, 2019); none of the profits went to the Tennessee Children’s Home Society. She gouged prospective parents on everything from travel costs, to home visits, and attorney’s fees, pocketing up to 90% of those payments (Noll-Wilensky, 2019). But to the general public, Tann was seen as a motherly philanthropist who devoted her life to rescuing children-in-need.

During the 30 years Tann ran the Children’s Home Society, it is believed she made more than a million dollars from her children-trafficking operation- about $11 million in today’s dollars (Celeste, 2019); however, she did not do it alone. Tann’s extensive child-trafficking operation required connections. Tann’s co-conspirators were authority figures, people not to be contradicted, leading both adults and children to follow them willingly. Such people include doctors, nurses, police officers, judges, social workers, and powerful political machines such as E.H. “Boss” Crump. In exchange for kickbacks, Crump would offer protection by providing false witnesses in Tann’s favour when complaints arose and helped seal adoptions by influencing the Tennessee adoption legislature (Harrington, 2020). Judge Camille Kelley, for thirty years, presided over the Tennessee juvenile courts, was another notable high-profile co-conspirator. Judge Kelley would notify Tann whenever a parent applied for assistance at the welfare department and would automatically award custody to her. It is estimated that he provided twenty percent of the children Tann put up for adoption (Celeste, 2019).

Tann’s operation began crumbling during the early 1950s, yet the mastermind and her co-conspirators have failed to receive consequences for the damage they inflicted. When Governor Gordon Browning was elected with the promise of ending corrupt politics in Memphis, Tann’s misdeeds were slowly unveiled to the public. Browning held a press conference the year of his election, highlighting only the financial aspect of Tann’s crimes, namely illegally pocketing money from the adoptions and failing to share her profit with the state-funded agency she represented. Within days of the press conference, Tann died of uterine cancer.

Although the Tennessee Children’s Home Society was shut down following Governor Browning’s press conference, Tann’s network worked furiously to protect their operation in her stead. In the years after Tann’s death, legislators in her circle worked to defeat proposals for investigations into the operation, in a desperate attempt to protect their own reputations. Shortly after, Tennessee Legislature passed the Public Acts of 1951 which made confidential all records “involving an adoption or attempted adoption of a person,” legalizing the adoptions that they financially benefitted from and in some cases, preserving their own adoptions. It was not until 1995 that the victims of the Tennessee Children’s Home Society had access to their birth certificates and adoption records, with some finding their birth parents (Celeste, 2019). But many of the 5,000 children adopted from Georgia Tann never saw their families again.

Despite almost single-handedly normalizing adoption in the U.S., Georgia Tann ran one of the most ruthless and wide-spread child-trafficking rings in American history that wrecked thousands of families and presided over the deaths and abuse of countless. To this day, black-market adoptions are still a salient problem internationally and no government has undertaken a reparations program to redress the afflicted families (Fieweger, 1991). Perhaps it is time to do so. Tennessee has the opportunity to pioneer a socially transformative program that can set the standard for similar reparations programs around the world, and it is without a doubt more than necessary.

References

Austin, L. T. (1992). Babies for sale: The Tennessee Children’s Home adoption scandal.

Bussiere, A. (1998). The Development of Adoption Law. Adoption Quarterly, 1(3), 3-25. doi:10.1300/j145v01n03_02

Celeste, E. (2019, December 5). For 20 years, a Tennessee baby thief kidnapped more than 5,000 children from the streets, hospitals, and shanty towns of Memphis. Now, 70 years later, survivors of her ‘house of horrors’ are confronting the past. Insider. https://www.insider.com/georgia-tann-tennessee-children-home-society-survivors-speak-out-2019-12.

Fieweger M. E. (1991). Stolen children and international adoption. Child welfare, 70(2), 285–291.

Harrington, R. K. (2020, July 25). Georgia Tann: The Mastermind of a Black Market Baby Ring That Lasted for Three Decades. Medium. https://medium.com/exploring-history/georgia-tann-the-mastermind-of-a-black-market-baby-ring-that-lasted-for-three-decades-f76c8175e4f1.

Holt, M. I. (1999). The orphan trains: Placing out in America. Boulder, CO: NetLibrary.

Jett, P. (2018, October 26). Georgia Tann: The Matron of Evil. Criminal Element. https://www.criminalelement.com/georgia-tann-the-matron-of-evil/.

Meet America’s Notorious Baby Seller, Georgia Tann. (2017, April 25). http://www.southernhollows.com/episodes/routine-papers.

Noll-Wilensky, H., Black-Market Adoptions In Tennessee: A Call for Reparations, 30 Hastings Women’s L.J. 287 (2019). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hwlj/vol30/iss2/8

Phillips, L. (2019, November 7). ‘Before and After’: Victims of Georgia Tann Adoption Scandal Share Stories in New Book. The Commercial Appeal. https://www.commercialappeal.com/story/life/2019/11/07/georgia-tann-adoption-scandal-before-and-after-lisa-wingate-judy-christie/4165494002/.

Raymond, B. B. (2007). The baby thief: the Untold Story of Georgia Tann, the baby seller who corrupted adoption. Union Square Press.

Wingate, L. (2017). Before we were yours: A novel. New York, NY: Ballantine Books.

Wingate, L., & Christie, J. P. (2019). Before and After: the Incredible and Heartbreaking True Stories of Victims of a Notorious Adoption Scandal. Quercus.