The Notorious Cocaine Trade

By Brendan Lacey

Frederick and Ermine Jung gave birth to their only child, George Jung, in the summer of 1942. George struggled in his academics, but had a relatively normal childhood experience. In his later adolescence years, he dropped out of college with aspirations to make money on his own. After moving to California and gaining experience in black market industries, Jung found his niche after meeting Carlos Lehder in prison. Lehder introduced him to Pablo Escobar, the leader of one of the most dangerous drug organizations of all time, the Medellín Cartel. Coming from Boston, Mr. and Mrs. Jung could have never imagined their child becoming one of the most influential leaders in the cocaine market of the 1970s. However, there were many factors that contributed to the prosperity of the black market other than the intelligence of individuals like George. In fact, the suggested reasons for the resounding success of the Medellín Cartel’s operation outweigh the contributions made by its leaders. We will begin with exploring the effects of worldwide globalization, transition into the unsuccessful steps taken by regulators, and then conclude with how the American culture influenced the cocaine demand while Americans were benefiting from an economic recovery.

To begin, the effect of international trade and increased globalization is key when examining the success of the cocaine trade. After World War II, the world saw a massive increase in foreign trade and less restriction on international commerce. The value referencing the quantity of exports worldwide increased by 433% from World War II up until the formation of the Medellin Cartel in 1976[i]. This large increase in the amount of worldwide exports displays the magnitude of changes in foreign transactions. Legal markets around the world were able to benefit from the international exchanging of goods. Additionally, illicit markets, including the cocaine trade, were able to profit off of globalization.

As previously mentioned, economic agreements between countries to reduce trade tariffs resulted in greater international activity. Black market activity grew as a result of these changes. Before globalization, many underground economies did not participate in transnational activity. This could have been due to strict pre-globalization restrictions on international trade that made it very risky to do business across country borders. However, post-WWII globalization offered new technology and ways of communication between black markets around the world through the encouragement of free trade[ii]. Criminal organizations like the Medellin Cartel were able to form and invite syndicates like George Jung into their business operations. Jung, a kid from Boston, would have never been able to involve himself with people like Pablo Escobar without the free movement of people that globalization had incited.

Government organizations did nothing to combat international black market activity. Most black markets are solely focused on maximizing their profits. For the cocaine trade within Colombia, the United States proved to be the best market for their product. The Medellin cartel was a ruthless organization bent on destroying western civilizations[iii]. Cocaine trafficking was so successful because the black market leaders were able to take advantage of the U.S. This idea is present throughout the entirety of this paper, but when it comes to globalization there were no restrictions or steps taken to discourage illegal foreign activity. International cooperation amongst foreign governments was needed to decrease black market activity that found its way into the United States[iv]. The United States and Colombia failed to cooperate initially, allowing the cocaine trade to immensely benefit from globalization.

The United States’ war on drugs has been a complete failure in the eyes of many[v]. Richard Nixon declared the war on drugs in 1971 with the intention to decrease illegal drug trade activity in the United States. We have discussed the ineptitude of the United States to communicate strategically with foreign governments, but government actions taken inside of the country were much more destructive. Nixon’s movement led to the arrest and incarceration of millions of people, destroying individual and family lives nationwide[vi]. Unfortunately, the war on drugs focused on putting more people in prison rather than locating the source of illicit markets. As a result, millions of American lives were negatively affected by the government’s decisions, all while the illegal exchange of drugs remained unaffected.

Political actions also didn’t account for corruption inside of government agencies. Profits in the cocaine trade were very lucrative. Government officials were targeted and bribed by black market leaders in an attempt to provide security for the illegal cocaine trade. An example of this appears in an 1989 New York Times article showcasing seven government agents being indicted for their involvement with the Medellin Cartel[vii]. Ineffective government action not only hurt the American people, but led to the strengthening of the illicit cocaine trade through the corruption taking place inside of U.S politics.

Additionally, the cocaine market benefited from the economic cycle occurring in the United States at the time of the Medellin Cartel’s formation. The cartel formed in 1976 as the U.S started to recover from a two year economic recession. GDP growth in the United States was upwards of 5% every year for four years after 1975[viii]. The American people were starting to have more money in their pockets and the illegal drug trade was able to benefit from the increase in their consumers’ willingness to spend. There was no better time for the cartel to form than during an economic recovery.

With more money in the hands of the people, Americans looked for ways to spend it. This brings us to a crucial contributor to the success of cocaine trafficking. With cocaine coming in from Colombia in the 1970s, pop culture in the United States started to normalize cocaine use. While looking for ways to spend their money, Americans felt that it was normal to participate in the purchasing of cocaine due to the media glamorizing the product. A Newsweek article in 1977 glorified the drug’s effects and undermined the dangers of it. The article states, “A little cocaine, like Dom Perignon and Beluga caviar, is now de rigueur (required by etiquette or current fashion)… the user experiences a feeling of potency, confidence, and energy”[ix]. George Jung and Pablo Escobar had the perfect product for upwardly mobile citizens[x] looking to spend their newly acquired capital. From seeing it on TV, in movies, magazines, newspapers, etc., the American people’s demand for cocaine rose with cultural influences.

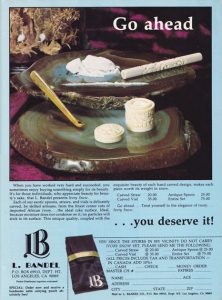

Therefore with the influence of pop culture on everyday Americans, consumption of cocaine kept going up while the price went down due to the increased demand for the product over time[xi]. The cocaine craze of the 1970s is a prime example of how propaganda and the media can influence people’s decisions. Cocaine was seen as a luxury rather than a drug. The following images are advertisements involving cocaine from the 1970s and 80s. As one can see, these ads had little intention to showcase the negative implications of the drug.

The cocaine trade’s success can be attributed to much more than solely the decisions of a few individuals. Increased international activity opened the door for black market activity across country borders. Cocaine trafficking flourished with less regulation and more cooperation amongst different countries, including the United States. Incompetence of the United States government while hunting down the source of the cocaine trade enabled the black market to be successful for as long as it was. Government policy enacted was destructive towards U.S citizens, while corruption inside of government agencies allowed the Medellin Cartel to profit off of the American people. Furthermore, the cocaine business benefited from pop culture’s influence on everyday U.S citizens. Demands for cocaine rose with the normalization of cocaine usage by different media sources across all of the United States. With high demand, people like George Jung and Pablo Escobar had no issue smuggling tons of cocaine into the United States and thus profiting off of individual vices. From globalization, political/economic instabilities, and cultural influences, there is no sole reason for the prosperity of the cocaine trade. Ultimately, these many factors worked together to create one of the most menacing illegal markets humans have ever encountered.

[i] Federico, Giovanni and Antonio Tena-Junguito (2016 b). ‘A tale of two globalizations: gains from trade and openness 1800-2010’. London, Centre for Economic Policy Research. (CEPR WP.11128).

[ii] Petcu, Cristina. “(PDF) Globalization and Drug Trafficking.” ResearchGate. The New School, 15 May 2017. Web. 25 Oct. 2020.

[iii] Glenny, Misha. Mcmafia: A Journey Through the Global Criminal Underworld. New York, N.Y: Vintage Books, 2009. Print. (Pg. 251)

[iv] “EFFECTS OF GLOBALIZATION, MARKET LIBERALIZATION, POVERTY ON WORLD DRUG PROBLEM AMONG ISSUES RAISED AT ASSEMBLY SPECIAL SESSION.” Press Release. United Nations, 9 June 1998. Web. 25 Oct. 2020.

[v] Glenny, Misha. Mcmafia: A Journey Through the Global Criminal Underworld. New York, N.Y: Vintage Books, 2009. Print. (Pg. 251)

[vi] “The ‘War on Drugs’ Has Failed, Commission Says.” The Leadership Conference Education Fund. Civil and Human Rights Organization, 15 Mar. 2019. Web. 25 Oct. 2020.

[vii] Berke, Richard L. “AGENTS ACCUSED: THE DRUG FIGHT’S DARK SIDE – A SPECIAL REPORT: Corruption in Drug Agency Called Crippler of Inquiries and Morale.” NyTimes. New York Times, 17 Dec. 1989. Web. 25 Oct. 2020.

[viii] Amadeo, Kimberly. “An Annual Review of the U.S. Economy Since 1929.” The Balance. 13 Mar. 2020. Web. 25 Oct. 2020.

[ix] “Thirty Years Of America’s Drug War | Drug Wars | FRONTLINE.” PBS / WTIU. Public Broadcasting Service. Web. 25 Oct. 2020.

[x] Glenny, Misha. Mcmafia: A Journey Through the Global Criminal Underworld. New York, N.Y: Vintage Books, 2009. Print. (Pg. 245)

[xi] Glenny, Misha. Mcmafia: A Journey Through the Global Criminal Underworld. New York, N.Y: Vintage Books, 2009. Print. (Pg. 262)