The Real Life Dallas Buyers Club

by Leah Roebuck

In 1985 Dallas, Texas, Ron Woodroof received news that would change his life forever: he was diagnosed with AIDS. Doctors said he had thirty days to live; however, with little help from mainstream medical institutions, he managed to live another seven years.[1] He survived by using a combination of experimental drugs which he smuggled into the United States and sold to local AIDS patients through the Dallas Buyers Club, one of several local distribution organizations throughout the US at the time. In 2013, director John-Marc Vallee brought Ron’s story and the story of his founding of the club to the big screen. The movie, Dallas Buyers Club, accurately shows how a combination of social stigmas, government inefficiency, and geographic convenience created the perfect environment for a tight-knit black market for experimental drugs to arise. This club ultimately made the difference between life and death for hundreds of people including its founder.

The HIV/AIDS epidemic of the 1980s brought with it a mountain of social stigma because of the populations it hit the hardest. While in its infancy in the US, the disease “was largely seen as primarily affecting gay men, prostitutes, and drug users” which led to discrimination from both peers and healthcare professionals who would often refuse to go near patients with AIDS.[2] AIDS spread rapidly among a population that many at the time, including politicians and healthcare workers, largely saw as expendable. Even Woodroof himself held homophobic views prior to his diagnosis. Early in the movie, Ron and his friends repeatedly use the f-slur in reference to the gay community, and after his AIDS diagnosis, Ron’s friends and family abandon him.[3] In an interview shortly before his death, Woodroof admits that “his illness and interactions with gay AIDS sufferers through the buyers club changed his views on gay people.”[4] Because the AIDS virus spread through populations that the general public viewed as expendable, research into finding a cure was not seen as urgent. The virus brought with it not only medical complications, but also a social stigma and political discourse that put it low on the government’s priority list.

As a result of the negative social stigma surrounding the AIDS epidemic, finding accurate information about the virus proved a difficult task, and the government moved slowly to correct the confusion. This sluggish pace started from the very beginning of the epidemic. It took a year for the CDC to even announce the existence of AIDS, another year to determine all the modes of transmission, and another year to discover the cause of the disease, the HIV virus. Then, during the height of the epidemic, “the FDA and CDC provided little information about HIV/AIDS, how it spread, how to protect oneself, how the disease progressed in those infected, and other vital information about the disease.”[5] So much confusion surrounded the disease that even after a doctor diagnosed someone with AIDS, they may not believe they have it. This was the case for Woodroof. He ignored his diagnosis for a long period of time because he believed it had to have been a mistake since he was not homosexual. As depicted in the movie, it was not until he conducted his own research through TIME magazine that he learned that heterosexual men could contract the disease too. Only then did he begin taking his diagnosis seriously.[6] With so much misinformation and fear surrounding the disease, combined with a snail-like government response, it comes as no surprise that many in the AIDS community became skeptical of the government’s ability to handle the disease even early on in its progression.

This early apprehension towards the government only worsened throughout the epidemic’s progression. Even as the government began to release drug treatments to help AIDS patients, many still believed that “the government and pharmaceutical companies [were] conspiring to play God with their lives—and are trying to make money by limiting the number of AIDS drugs on the market.”[7] Trials for an experimental drug called AZT were extremely limited with only a small percentage of patients making the cut. Additionally, the FDA standard procedure to approve a drug at that time took 8 to 12 years.[8] Anyone with an AIDS diagnosis likely would not survive even half of that time. For most AIDS patients, there was no legal option for obtaining any medication that could extend their life. An AIDS diagnosis was essentially a death sentence, and patients saw very little progress by the government to change that outcome.

To make matters worse, concerns about the timeline of drug approval came second to fears surrounding the effects of the drugs themselves. In the movie, Woodroof learns from a doctor in Mexico that “the only people AZT helps are the people that sell it. It kills every cell it comes in contact with.”[9] These kinds of rumors about the effectiveness, or lack thereof, of government-sponsored treatments like AZT led to a deeply rooted distrust for mainstream medical institutions. When the institutions people usually look to as sources of information can no longer be trusted, that sense of fear leads them to seek help elsewhere.[10] For members of the AIDS community, knowing that pharmaceutical companies may have had ulterior motives, and that the chances of being accepted into a government trial were slim, they felt no other choice but to take matters into their own hands.

For Ron Woodroof, the search for an alternative treatment for the virus led him just across the border into Mexico. He met a doctor there who gave him several drugs which treated different symptoms of the AIDS virus. Luckily, smuggling the unapproved substances across the border required only the most basic precautions. As Woodroof describes it in an interview with Dallas News, “if you’re just a little bit careful, they ain’t never going to nab you.”[11] He loaded the drugs into his car which he equipped with heavy-duty shocks to prevent sagging from the weight of the substances. To disguise his personal appearance, he dressed as both a doctor and a priest—as depicted in the film—to get across the border.[12],[13] Those tactics continued to work for him even as he expanded his smuggling internationally. Many countries, including England, Germany, Japan, and Denmark had approved products to combat the AIDS virus, and Ron had contacts in all of them.[16] Of course, the larger the operation grew, the riskier it became. For Woodroof and the other members of the Dallas Buyers Club, however, the risk of being caught smuggling drugs internationally was well worth it if it meant living a few more months. The relatively lax border control and regulatory discrepancies between countries just made that mission a little easier.

Luckily for Woodroof, distribution remained localized and therefore required much less secrecy to execute. While AIDS certainly affected people in all parts of the United States, buyers clubs existed in several major cities, making them tight-knit organizations. Buyers clubs existed in “Dallas, Ft. Lauderdale, New York City, San Francisco, and many more cities” each with a few thousand members.[17] This scope sets the buyers clubs apart from other drug organizations. They never focused on expansion into new territories or had to compete with one another for customers. Each club focused on its own community, and occasionally worked with other cities to spread information on treatments or supply sources. Unlike other modern illegal operations which it seems “will always strain to expand beyond the boundaries of physical and political space,”[18] the buyers clubs operated within a very narrow scope. Not only were they geographically limited to their local area, but they were also demographically limited in their customer base. They kept operations focused on a specific subsect of the population in their specific geographic area and prolonged hundreds of lives as a result.

The success of the buyers clubs and the inefficiency of the government’s response to the virus led many physicians to support the efforts of buyers clubs, albeit quietly. This connection to legal institutions manifests itself in the film through the character of Dr. Eve Saks, played by Jennifer Garner. Although that character is fictional, she represents the culmination of hundreds of real-life supporters of the buyers clubs. In one instance, a 1991 New York Times article revealed that one doctor gave his patient the number of his local buyers club so that he could access drugs that would otherwise not be available to him.[19] This situation was not unique at the time. While doctors were hesitant to openly support the illegal sale of drugs for obvious reasons, they saw the benefit these organizations had for an otherwise hopeless population. One Dallas doctor, Dr. Alan Hamill, even claimed that he “would be willing to chain himself to the door of Ron Woodroof’s operation in a demonstration of support.” Several other respected professionals including doctors, lawyers, lab technicians, and more shared similar sentiments.[20] As corrupt as it may seem, it is not uncommon for criminal organizations to have connections in the legal market. In fact, many crime organizations front as legal operations such as insurance companies.[21] The difference with the Dallas buyers club, however, was that they had not only connections, but endorsements from professionals in positions of authority. These supporters essentially recruited members for the club and played a large role in allowing buyers clubs to thrive.

The main factor that set buyers clubs apart from other black market organizations comes down to the motivation. While other drug smugglers have profit as their main incentive, Woodroof and other AIDS patients do it to survive. In many ways, this meant their operations willingly took on more risk because they had so much more at stake. Whereas actors in other black markets can abandon ship when things become to risky, buyers club members do not have that same luxury.As Woodroof puts it, “it is not a matter of whether or not you want to take these risks, it’s a matter that you have to take these risks.”[24] This risk-taking behavior applies not only towards breaking the law in order to obtain and distribute the illegal drugs, but also towards taking drugs that are not FDA approved. Patients whose days are numbered have very little reservations about taking potentially harmful drugs. The slight possibility that the drugs could prolong their lives makes them worth the risk and made the buyers clubs hard to stop. This sets buyers clubs apart from other black market operations in which “neither the supplier nor the consumer understands [their] relationship in anything other than economic terms.”[25] For those involved in buyers clubs, the economic portion of their relationship comes last. The club exists as a last resort for people fighting for their lives, not for profit. Without the life or death stakes, these organizations would not exist. They were designed so that people could have another chance at life, not to make a profit.

Overall, the movie Dallas Buyers Club accurately depicts the black market activities taking place in 1980s Dallas Texas involving the sale of unapproved substances to treat the AIDS virus. In an environment of social stigma towards AIDS patients, an inefficient and untrustworthy government, and lax border control, the Dallas Buyers Club arose as a tight-knit community with support from industry professionals. What really set them apart, however, was the desperation for life. If the Dallas Buyers Club did not exist and continue to thrive, many lives would have been lost to the AIDS virus, including Ron Woodroof’s. These illegal organizations gave hope to a population that otherwise felt abandoned by their government and fellow citizens. Motivated not by money, but by survival, members of these organizations found ways to thrive when all the odds were against them.

Citations

[1] Harris, Aisha. Slate.

[2] Philpott, Sean. The Conversation.

[3] Vallee, Jean-Marc. Dallas Buyers Club. (21:40, 22:22, 35:17)

[4] Dockterman, Eliana. Time.

[5] Dorf, Hannah. Health & Medicine in American History.

[6] Dockterman, Eliana. Time.

[7] McNary, Chris. Dallas News.

[8] Dorf, Hannah. Health & Medicine in American History.

[9] Vallee, Jean-Marc. Dallas Buyers Club. (39:39)

[10] “Factors Underlying Cialdini’s Six Principles .” Techniques for Changing Minds.

[11] McNary, Chris. Dallas News.

[12] Vallee, Jean-Marc. Dallas Buyers Club. (43:57)

[13] Dockterman, Eliana. Time.

[14] “FDA Agent Questions Woodroof.” Screenplay HowTo

[15] Vallee, Jean-Marc. Dallas Buyers Club. (44:39)

[16] McNary, Chris. Dallas News.

[17] Dorf, Hannah. Health & Medicine in American History.

[18] “Gilman et al. Deviant Globalization, 2–19.

[19] Harris, Aisha. Slate.

[20] McNary, Chris. Dallas News.

[21] Glenny, Misha. McMafia, 14.

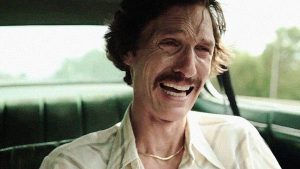

[22] “Matthew McConaughey, ‘Dallas Buyers Club’.” Zimbio

[23] Vallee, Jean-Marc. Dallas Buyers Club. (37:10)

[24] McNary, Chris. Dallas News.

[25] Glenny, Misha. McMafia, 18.

Works Cited

Dockterman, Eliana. “The True Story of Dallas Buyers Club.” Time, Time USA, 8 Nov. 2013, entertainment.time.com/2013/11/08/the-true-story-of-dallas-buyers-club/.

Dorf, Hannah. “Managing Your Own Survival: Buyers Clubs in the AIDS Epidemic.” Health & Medicine in American History, Grinnell College, 17 May 2018, lewiscar.sites.grinnell.edu/HistoryofMedicine/spring2018/managing-your-own-survival-buyers-clubs-in-the-aids-epidemic/.

“Factors Underlying Cialdini’s Six Principles .” Techniques for Changing Minds, Changing Minds, changingminds.org/techniques/general/cialdini/underlying_factors.htm.

“FDA Agent Questions Woodroof.” Screenplay HowTo, 19 Apr. 2014, screenplayhowto.com/beat-sheet/dallas-buyers-club/.

Glenny, Misha. McMafia: A Journey Through the Global Criminal Underworld. 1st ed., Vintage Books, 2019.

Harris, Aisha. “How Accurate Is Dallas Buyers Club?” Slate, The Slate Group, 1 Nov. 2013, slate.com/culture/2013/11/dallas-buyers-club-true-story-fact-and-fiction-in-the-matthew-mcconaughey-movie-about-ron-woodroof.html.

“Introduction.” Deviant Globalization: Black Market Economy in the 21st Century, by Nils Gilman et al., The Continuum International Publishing Group, 2011, pp. 2–19.

“Matthew McConaughey, ‘Dallas Buyers Club’.” Zimbio, www.zimbio.com/A+Method+to+Th eir+Madness+Stars+Who+Went+Way+Too+Far+for+Their+Roles/articles/Yjs_V21PtVS/Matthew+McConaughey+Dallas+Buyers+Club.

McNary, Chris. “Buying Time: World Traveler Ron Woodroof Smuggles Drugs – and Hope – for People with AIDS.” Dallas News, The Dallas Morning News, 9 Aug. 1992, www.dallasnews.com/news/1992/08/09/buying-time-world-traveler-ron-woodroof-smuggles-drugs-and-hope-for-people-with-aids/.

Philpott, Sean. “How the Dallas Buyers Club Changed HIV Treatment in the US.” The Conversation, The Conversation US, 6 Feb. 2014, theconversation.com/how-the-dallas-buyers-club-changed-hiv-treatment-in-the-us-22664.

Vallee, Jean-Marc, director. Dallas Buyers Club. Truth Entertainment Voltage Pictures, 2013.