4 University of the Underground

From ticket scalping, “plugs,” fake IDs and selling homework, to drugs ranging from coke to Adderall to caffeine – black markets on college campuses are complex, diverse, and extreme. This ecosystem is a spider-web of connections, networks, and complex organizations that evade standard detection and generate endless supply and demand. College campuses are a stand-alone economic enterprise, creating a microclimate where licit and illicit tangle together.

“$45 for a cart,” I read off my phone. My friend, Hannah[1], scoffs. “Styles sells his for $30,” she says, turning her phone around to show off her dealer’s digital platform, an untraceable universe of cannabis products ranging from key-lime weed cartridges to white chocolate edibles. Complete with a flashy menu, deals of the day, and an organized system of delivery drivers, Styles isn’t a rookie in the market. Unlike Jake, a freshman in my computer class, who boasts a fake ID and number of Snapchat plug connections. Asides from the cartridge, Jake lets me know that “the bud I buy off this one guy, he always has fire strands.” Within the hour, Hannah had placed and received her order, and within 10 minutes, a handful of invisible sources were ready to fill mine. With the Snapchat notification cue, Hannah empties out a backpack and heads out to the dorm’s dumpsters. She hops in the car and briefly chats with the driver, Styles himself today, before he plunks a handle of Fireball on the dash and slips her a bag of cartridges and cherry-red gummy bears. For the deal of the day, she earns a free joint. She takes the stairs, greets the RA, and unloads her stash into the dresser, replacing her notebooks and computer back into the bag. With expert fingers, Hannah tosses the empty cartridge and replaces it with the fresh key-lime flavor imported from California. She seems content now, lighting a candle and settling back to bed and taking a long drag from the pen, the fumes of teakwood and cotton to combat the sickly-sweet smell crowding the space. Styles and Jake. One, a community member, one a student, both serving the city’s sprawling black-market system and university students alike.

The digital landscape on college campuses creates an easy entrepreneurial route that inhibits incredible black-market activity. Suppliers and consumers have an instant handful of connections, customers, and communication styles at their fingertips – on platforms ranging from general SMS, social media sites, and digital payment services. The vast expanse of this group ensures a multi-sourced flow of black-market activity – as smaller sources link together to create a flow of complex markets. As these tributaries break off into even smaller arteries, the connecting web becomes untraceable. There is not one seller, one stream of illicit activity, nor the ability to distinguish a specific “supplier.” RA’s, residential neighbors, mini marts and gas stations, the freshman from your business group, an old roommate who just turned 21 – suppliers and consumers alike blur together. Suppliers may be consumers and vice versa, but every party involved chases or generates one common denominator: money.

Everyone has a hustle. Academically, students are motivated to achieve good grades, maintain financial stability, and find time for a social life, while under pressure to pull it off effortlessly. Outside of academics, hustle culture shapes a money-making, entrepreneurial spirit. At a BIG-10 University in the Midwest, one student capitalizes on fraternities placed on cease and desist by renting his off-campus house as a party venue. For $800, plus the promise to clean up the next-day’s mess, the frat sets up trash cans of booze and an impressive speaker system, ready to party until the night grows old – or the neighbors decide to call the police. One person who thinks differently than the rest, who innovates and fills demand, has the opportunity to succeed. The more you have to offer in a complex economy, the more you can gain from it. Or, if you’re hustled – the more to lose. Undefined systems have less structure and less safety nets in place – so those who are hustled have less of a protective backdrop to ensure reparation, or in a ticket scalping case, compensation.

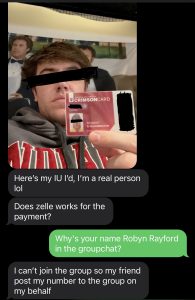

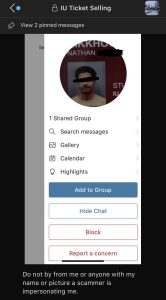

A private, well-run ticket selling group chat is the perfect place to fairly sell, trade, and exchange sporting good tickets. Potentially, in a utopia. At Indiana University, the largest running ticket selling group chat has become shark-infested waters tinted with crimson, hold the cream. Boasting over 6,000 members, the platform has become the wild west for scam artists, duplicate tickets, price gouging, and identity theft. “Students” selling “tickets,” request payments through digital payment services Cash App, Zelle, or Venmo. The shadowy veil of online communication allows anyone to become anyone. One scammer sent a photo of their Student Identification to prove their validity, when the name of the card doesn’t match to the name of the seller you’re working with. Another stole the name of an Indiana student and used it as an alibi, so if a customer independently looked “Catie Goodwin” up, she’d appear to be a university student, and therefore trustworthy. A buyer makes the payment and never receives the ticket or is sent a faulty ticket instead. Tracking down these scam artists is tricky. Most change their names after the exchange, and with a weak paper trail due to digital payment – action is futile. In this undefined system – a ticket selling based on trust – the hustlers and the hustled are cognizant of the absent safety net below them.

The opportunity at hand – unlimited demand and limited resources – is a golden opportunity for hustlers to capitalize on licitly. Up charging is a licit practice, although wavers on the moral compass as to how much sellers will charge. With limited seating to university sporting events, ticket demand runs rampant, and hustlers capitalize. An Indiana University student football package costs $105, averaging to a $15 ticket per home game. A football ticket sold for $50 equates to a $35 profit. Lora, an undergraduate student at Penn State University Park, touched on the demand for Penn State football tickets, students fighting in 1,000+ member group chats for the chance to buy season ticket packages for 2-3 times the original price of $246. Depending on the value of the game, the success of the season, and the opponent, sellers at various universities often charge over 100% of the base cost. Basketball is its own economic force. Purdue-Indiana tickets for the 2022 home game sold for well over $100, and North Carolina-Indiana student basketball tickets for the 2022 ACC-Big Ten Classic were resold for a max of $300 a pop. Negotiation, compromise, and exchange funnel into this licit business exchange, while in parallel, other buyers lose $300 to a fake seller toting “3 UNC Tickets Text Me Here.” Licit and illicit coexist in this mega-chat, with licit hustlers catering to hungry consumers, mingled with illicit hustlers searching to exploit them.

Risk doesn’t stop the hustle when there’s a greater reward on the horizon – an endless consumer base charged by desire. Desire is the fuel for black market activity on college campuses, encouraging stability on both the consumer and supplier end. Using illegal substances – whether it be alcohol or any other blend of drugs – equates to fun. Medicated drugs like Vyvanse and Adderall equate to focus, psychedelics create an experience. As Propagandist Edward Bernays said, “Human desires are the steam which makes the social machine work.” (Bernays) The list stretches on, desires ranging from fun, good grades, escapism, and more. When these desires are capitalized upon, demand can be manipulated to target consumer susceptibility and gullibility. “Modern propaganda is a consistent, enduring effort to create or shape events to influence the relations of the public to an enterprise, idea or group.” (Bernays) Individual desires mold consumer needs, drive societal wants, and determine another key aspect of black-market activity – the value consumers are willing to pay for the product in hand, or – in cup.

The measure of value is crucial to collegiate black-market activity, and it’s taught right in your Gen-Ed Economics class. “How would you measure the value of a city’s black-market activity?” I ask, after spending an hour studying the licit horizontal market measurement. My econ professor leans back against the wall, rubbing the end of his chin. “That’s not easy at all,” He chuckles. “Unless you go straight to the source, you could try comparing the market to other places where the substance is legal, find the price and apply that to an estimate here.” That, considering if the substance in question is legal at all. Perhaps I’m overlooking the most common drug of them all, injected into the famously recognizable drinks loaded with college students’ fuel of choice – caffeine. The Venti-sized cups positioned on every desk corner, held in every hand, and sought in between classes – Starbucks has carved its place on university union buildings and dorm lobbies across the country, boasting over 300 campus locations. Texas A&M hosts the three most profitable Starbucks locations on any college campus, selling an average of 119 gallons of coffee a day and totaling around 3,700 transactions a day. (Reid) Students value energy and embedded in the value of the drink comes the social experience, an ambient place to study, and an imprintable habit to form. Students want more caffeine, or at least the student who caused one barista to ask another how to make a drink with nine shots of espresso. Canned energy drinks are stocked at every mini mart and campus store, while supplements and creatine line supermarket shelves, the value of energy makes caffeine a popular campus drug of choice.

Social proof and group characteristics are strong underlying connections between desire and value for black market activity. Robert Cialdini’s Principle of Influence, coins social proof as “We copy what others do, especially when we’re unsure.” (Cialdini) As a mini society, “the mind retains patterns which have been stamped on it by group influences, for the group mind in place of thoughts it has impulses, habits, and emotions.” (Bernays) College is known as a period of experimentation – academically and socially. New students enter a unique landscape – new classes, new routines, new freedoms. With this uncertainty, this newness, younger undergraduate students tend to mirror the actions of what they’ve heard, seen, or concluded about the coined “college experience.” From family, friends, media, movies and more, students are exposed to broad popular tendencies and potentially preconceived ideas of legality, illegality, and social norms before they even reach the university. The college experience, while heavily influenced by a series of psychological factors, also relates to the physical environment and surroundings students join the moment they set foot on campus.

Neighboring zones and geographical location play a critical role in black market activity. At one BIG-10 midwestern college town, the campus invigorates the city life – home to vibrant nightlife, countless bars, and a sizzling energy. Besides the surrounding city, it’s vital to dive deeper into the structural organization of the campus itself, specifically residential halls. As a freshman, but up to all four years, college students spend time in a dorm, close-quartered, uniformed living facilities.

Gang Leader for a Day, in which Sociologist Sudhir Venkatesh explores Chicago gang-life, touches on the way housing projects function in operation. It’s crucial to note the circumstances and settings are vastly different between housing communities in Robert Taylor and residence halls on college campuses; the objective of this analogy is to compare similarities in the building structure and concept – rather than the socioeconomic pressures and societal lens. Venkatesh, during his time with the Chicago gang in the late 20th century, noted the following in regard to the structure of Robert Taylor’s housing units.

Robert Taylor buildings were built in a stifling manner, crowded onto a small parcel of land and leaving vast vacancies in between. Due to the compactness of Robert Taylor, police presence was sparse, police deeming Robert Taylor “too dangerous to patrol.” Tenant leaders ran their assigned buildings and maintained order over their property. The buildings expressed a great sense of community – residents becoming almost inseparable from the building itself. Tenants helped each other, hosted birthday parties and celebrations, and provided services through trade, exchange, and sale. (Venkatesh)

College campus dorms are structured in the following way. RAs are appointed to maintain control on each residential floor. Quarters are tight-knit, and replicative of each other. Many students befriend others on their floor, create memories that will encourage nostalgic recollections, and share much of their lives together – whether it be a community bathroom, a pizza, or homework. Dorms are a community, and as Venkatesh notes, “The community is a relationship.” In standard society, you typically do not reside in a building with similar-aged companions or share identical interests – like attending the same University, sharing the same living-space, sporting the same role to “society” – a full-time/part-time student. Common interests span a further list – sharing a similar major, recognizing someone from your hometown, a hated passion for the same class, season sporting tickets. In this spirit-infested community, the influence of liking and similarity work in conjunction to form a unique bond.

Off-campus housing is a similar scene – tight-knit neighborhoods of similar aged residents sharing common interests. Wrapped all together – on-campus and off-campus housing, and nested into a city that feasts off economic activity from the campus, we have ourselves a small society. Here, the city community and university feed off of one another. In small subsets of society like these, black markets are an entirely unique game, the ecosystem operating with its own complete set of rules, blurring the line between clean and foul play.

Project housing and dorm-style living – although different in socioeconomic and societal lens – share fundamental similarities that create a unique platform for black market activity to thrive. Both are viable systems to crank out and ingest vast amounts of illegal activity. For the Black Kings of Robert Taylor, that activity was primarily cocaine. For the students, dealers, and other suppliers that form campus markets, that activity could be nicotine, marijuana, cocaine, Adderall, Vyvanse, sex, alcohol, and more. The reputation of each structure, and the level of law enforcement however, is a stark night and day difference, which ultimately define contrasting perceptions of these communities – one a community of academically stimulated individuals, and the other – a gang of ruthless criminals.

While society views these communities differently, both are inherently tethered to a deeper emotional attachment. Dorms are communities, they are relationships, just as the Robert Taylor housing projects were to tenants in Chicago. The demolition of the Robert Taylor community in the 1990’s was detrimental to tenants – the large majority had rooted their spirit and livelihoods in the building. Spirit-infested locations bind communities together, until the geographical location becomes inseparable from the community. When freshmen enter, live, and ultimately vacate their dorm, it’s a nostalgic experience. Whether students express excitement to be relieved of the close-quartered room, they’ll ultimately recall fond memories, late nights, and spirit of the experience. Students are the dorm, and the dorm is the students. This symbiotic relationship creates a close-knit community of students in like-age, similar circumstances, and lack of authoritative presence – the perfect platform for black market activity to explode.

Licit and illicit run parallel in college campus environments, intertwining to a degree in which they become tangled beyond separation. Consider the delivery-service GoPuff, which caters beer, seltzers, and a variety of other alcoholic beverages right to your doorstep. A licit company, complete with ID verification. So, when your fake ID passes the test, and the brown paper bag stamped with the teal GoPuff logo is handed over to an underage consumer, licit and illicit have just mingled. At another scale, doctor-prescribed Adderall, Vyvanse, and Ritalin medications, meant to assist students, are turned around and sold by the pop, crushed and snorted off countertops. A licit action, prescribing medication, turned illicit by the action of the beholder. Alas, licit and illicit have blended in a way where it’s impossible to incriminate the source – oftentimes a licit source – and evident to see the widespread effect of the following illicit activity.

“Fake IDs don’t work well,” Lora admitted, acknowledging that since the majority of the population is underage, the bars and stores are very strict. “They work in select places. Vape stores, 9/10 chance you won’t be carded. Alcohol is different.” Cora, a student at a BIG-10 university in the Midwest, flashes me her fake from the Philippines, which arrived after flirting with disaster in the mail system. Cora’s ID works like a charm for prominently underage bars on campus, and even if it doesn’t, a slip of a $20 bill will change the bouncer’s mind. Grant, a student at another major university in the Midwest, worries his fake is too flimsy, but notes it has served its purpose so far. To surpass the Fake ID caveat, Lora shares a popular source – anyone older than the underage student. “Even if you yourself don’t know somebody over 21, your friend, roommate, sorority sister, fraternity brother, classmate, or anyone either is or knows somebody of age.” Legal purchases of alcohol transferred to underage consumers turns into illegal activity. Malachi, an upperclassman at a university on the west coast, said law enforcement tends not to care about marijuana use on campus and it’s a normal practice. It’s never checked for and people use it at parks, indoor and outdoor concerts. Considering marijuana is legal in California, this seems to be a common practice, compared to a university in a state where the substance is illegal – law enforcement is all over it. In these similar, yet different university systems across various states, legality and illegality flirt in tandem – leaving those who are in charge to distinguish the two with a hangover-sized headache.

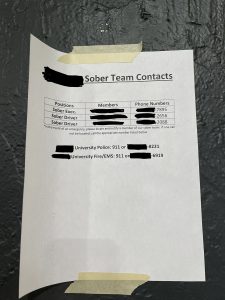

My Converse are glued to a BIG-10 fraternity basement floor by a mixture of berry seltzers and Natty lights. I’m looking at a sign taped to the wall, a simple chart listing the fraternity’s brothers in charge of maintaining sobriety for an executive position, driver, and chair. The city’s police phone number and EMT is listed at the end of the page. I pulled an exec member aside, Chevy, who I’d gotten to know during my short visit to the northern Midwest. “How are the police involved here when you have underage alcohol consumption?” I ask, throwing in an “I’m just curious” and a shrug. I was curious how a university, law enforcement, and community alike knew the activity that went down on Greek row yet turned a blind eye. Chevy takes a sip of his drink. “Well, the IFC is a big part of things.” I nodded, knowing that, from talking to another university frat brother, who coined the Inter Fraternity Council as “the ultimate wall between the University, law enforcement, and Greek Life.” Chevy continues. “Basically, everything is regulated, and the police don’t push too much. They showed up last night. But our Sobers just made sure the alcohol was out of view.” Chevy smiles and starts nodding his head to the new song pulsing through the hall. “Don’t worry too much about it,” He smirks, and pushes a Solo cup into my hand before dancing back over to the Pong table. I look into the murky liquid, and I realize I’m a long climb up the mountain of Busch Light, a lost walk across the crushed powdered tundra of coke, and only staring down the tip of the vast iceberg of a monstrous machine.

College campuses foster a unique black-market web, generating a microclimate where licit and illicit activity become intertwined. Legality and illegality run circles around each other, leaving loops, voids, and promoting progress to be made in the study of university black market systems. Within this complex web, desire, hustle, and influence runs rampant, blending with a unique societal structure that fuels the enterprise’s success and promotes its longevity. Black markets are permanent, and on university campuses, the underground economy thrives in its all-powerful ecosystem.

Sources

Bernays, Edward. Propaganda. Melusina, 2010.

“Cialdini’s Six Principles of Influence.” Cialdini’s Six Principles of Influence, http://changingminds.org/techniques/general/cialdini/cialdini.htm.

Corley, Cheryl. “’The Projects’ Explores the Evolution of Chicago’s Public Housing System.” WBEZ Chicago, WBEZ Chicago, 17 Dec. 2015, https://www.wbez.org/stories/the-projects-explores-the-evolution-of-chicagos-public-housing-system/3e509c88-d74f-467a-b2a8-4cac75d7f8be.

Reid, Kylee. “Caffeine on Campus.” Texas A&M Today, 5 June 2019, https://today.tamu.edu/2016/12/01/caffeine-on-campus/.

“The Robert Taylor Homes Open.” African American Registry, 8 Dec. 2022, https://aaregistry.org/story/the-robert-taylor-homes-opens/.

“Walnut Grove Center and Mcnutt Dining Addition (North Housing Addition).” Capital Planning & Facilities, https://cpf.iu.edu/capital-projects/projects/student-residence-new/north-housing-addition.html.

Venkatesh, Sudhir Alladi. Gang Leader for a Day: A Rogue Sociologist Takes to the Streets. 2009.

- Names have been modified to protect the identity of those involved with this work. ↵