9 Flower of the Golden Triangle

One day, a man went to the pulpit and testified that he was changed because of God. He swore God had given him his goodness and eternal life and saved him in this world. He preached that since the day God saved him, he hasn’t “hit number 4.” As he walked down, everyone applauded. I was confused, not knowing about “the number 4” and his testimony. I asked my mother, and she told me that only adults could know; I was 10. The next time someone gave testimony similar to that man, it was in a church camp. People shared their stories during a week full of sermons and prayers in cabins. The man remembered how he quit his number 4 addiction years ago when he met God. This time I asked my older sister what she meant by that. Once again, I was silenced; I was 13. My question was left unanswered. The third time I heard about number 4 was at a church conference. Once again, a man testified that he quit number 4 and his alcohol addiction. I was not sitting with my family this time, so I asked the internet what it meant.

I didn’t get the answers I wanted, mainly because of the language barrier. Translating the Burmese slang to English was a struggle I didn’t expect to encounter. So I asked my brother, and I asked him not to withhold the truth from me. Then, I found out that hitting the number 4 referred to using number 4 heroin. The answer only led to more questions. Why did it seem like many people in my community were addicted when they were young? Where did they get the drugs? And it seemed like the men that testified came from the same region of Burma. Why were there lots of drugs in the same region? I did not think those questions would be answered on the internet, knowing that my country seemed insignificant globally.

One day in high school, I heard someone talking about a major drug lord in Asia being Burmese, which piqued my interest. This was the first I heard about the Golden Triangle region. It checked out that the Golden Triangle region was near the same area where many people testified they became drug addicts. This at least answered where their drugs came from. The creation of major drug trade in the region is explained by the CIA’s support for the Koumintang (KMT) in the region, and the CIA’s support came from the idea that the KMT had been opposing the new communist China since the 1950s (sydpost et al.). The drug trade thrived with the CIA’s support and the United State’s ignoring the operation. The help from the CIA remained undetected for a while, and ordinary citizens would be baffled that a third-world country grabbed the CIA’s attention, which could be why not many people know about the CIA’s involvement. By the 1980s, the heroin trade in the Golden Triangle region became the second largest in the world. With the Golden Triangle region becoming the second-largest flow of heroin globally, it impacted the lives of many in the region and nearby, as one of the first bases of heroin consumption is right within the region and the surrounding areas. The hill tribesmen and migrant jade miners’ lives would never be the same.

[Need CLAIM sentence] The growth of the heroin trade in the Golden Triangle region started with the dream of KMT invading China and overthrowing the communist party (McCoy). For their socialist reason, the CIA backed them up and supported them. While in Burma, the CIA and the Truman administration supported the KMT to “block further Communist expansion in Asia. (McCoy).” The invisible cold war persists in many ways, working to fight against communism. The KMT was a socialist party pushed off China after the Chinese Civil War in 1949 (sydpost et al.). The KMT escaped into Southeast Asian countries like Burma, Thailand, Laos, and Taiwan. The KMT in the Golden Triangle region bought raw opium from hill tribes, turned opium into heroin, and used the sale of opium to operate their goal of invading China. General Tuan Shi-wen of the KMT in Burma explained that “to fight you must have an army… and an army must have guns, and to buy guns you must have money. In these mountains the only money is opium.” (129 McCoy ). Their desperation to use whatever could be valuable to their environment turned them to operate in the heroin trade that became the second largest heroin trade in the world. The KMT grew opium production and worked with the CIA to invade China to reclaim Yunnan province. In addition to the support from the CIA, the sale of heroin became their safety net. In 1951, they attempted to achieve their goals and invaded the Yunan province with the help of the CIA (sydpost et al.). Their attempt failed as they were pushed back into Burma. Their second attempt ended on a similar note as they were pushed back. The KMT’s overstay in Burma would be discovered by the Burmese government and kicked out of Burmese borders and into Thailand and Laos. In a series of events leading up to the eviction of the KMT from Burma, the Burmese government found evidence of the involvement of the CIA (McCoy). With the KMT out of Burma, other drug lords have taken the opportunity to expand their territory and power.

One of the most well-known drug lords of the Golden Triangle region was half Chinese and half Shan, Khun Sa. His reign in the area was the reason for the globalization of the heroin trade. Under his rule, the export of drugs in “the streets of New York” jumped from 5% to 80% from 1974-1994 (sydpost et al.). In twenty years, he expanded his operation, and his impact was felt through the streets of America as drug supplies increased. Aside from Khun Sa, multiple drug lords were fighting for territory and power in the Golden Triangle region with the promise of high profits. Due to the strife, residents paid taxes to the gang for protection, and the drug lords protected the merchants on their way to and from the trade. The drug lords also dictated which village the merchants could go to and buy heroin (journeymanpictures). The merchants then also paid taxes to the drug lord for protection and service. From then on, the merchants, often Chinese, traveled to Laos and Thailand to heroin refineries, transforming the brown and black sap of opium into pure powdered heroin (McCoy). Once the heroin is refined, heroin is transported to the international and local markets.

The heroin in the local market includes people in the Golden Triangle region, mainly the farmers of the opium themselves. The hill tribes of the Golden Triangle region are groups of poor ethnic populations that rely on growing opium to escape poverty. Opium is the cash crop that sells best and helps farmers stay afloat during their off seasons. Cut off from government social safety nets, they can rely only on their main cash crop for their livelihood. While they are the primary source of raw opium, they are also one of the first victims of opium addictions. In a vicious cycle of farming opium to escape poverty, they fall victim to addiction leading back to poverty. The money gained from opium cultivation is again used to buy opium to supply their addiction. The documentary “The Golden Triangle: Forbidden Land of Opium” explored the many reasons for smoking opium as an opium farmer. Xavier Bouman from the United Nations stated that they used opium as “medicine since their 20s… and take it as a painkiller” (The Golden Triangle: Forbidden Land of Opium). The addiction to opium in these hill tribes keeps the cultivation of opium steady as the farmers dive deeper into poverty and need to grow opium to stay afloat. In this region, additcion is so common that people show four fingers to indicate the birth of a boy since it means they will be addicted to drugs. Outside the Golden Triangle region, drug addiction turns from raw opium to more dangerous drugs like heroin and meth.

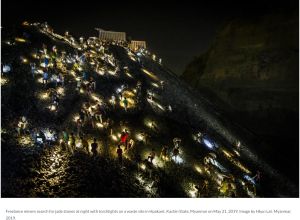

Heroin was a popular drug in the nearby regions and outside the hill tribes. The people that purchased heroin and the recovered addicts from the church were in the same region of the country. Young men in many ethnic groups in Burma leave their hometowns to search for work opportunities elsewhere. Some moved to cities like Mandalay and Yangon, while others moved to industrial regions like Kachin, where jade mining is popular. Similar to the Gold rush in the 1850s, jade mining in Burma attracted many people seeking wealth and an escape from poverty. They find a harsh reality in the mining town where drugs run rampant. The black market of jade mining is a critical topic causing the town to go into a similar vicious cycle of poverty, like the farmers in the hills tribe. Much of the mined jade was illegally sold to China or the government, keeping much of the profit from the miners. In these instances, many people turn to drugs to de-stress and so the use of heroin and meth in mining towns becomes popular. These mining towns were where the recovered addicts from church had worked in their youth, their stories were similar about the abundance of drugs in the town and how everyone seemed to do it. “It is so high that 90 percent of workers in some jade mines use it. So high that if you go to a gas station in Muse, which borders China, you are likely to get syringes as change (The Burmese do so much heroin that syringes are used for currency, 2021).”

To de-stress from a long day, people inject heroin using syringes, and as they use more and more drugs, they care less if the syringes are clean or have been used by others and only care about the next dose. As they fall into addiction, they are in vulnerable situations where they can contract HIV through dirty syringes. Florance Looi from Al Jazeera English youtube channel stated, “non-governmental organizations in Kachin state say they collect up to 40,000 used needles every day in just three mining towns.” Heroin usage by the miners allows them to work long hours without a break and get more jade to trade (PBSNewsHour, 2014). There are also other side effects of using heroin, many that we know harm people’s life. They had to supply their need for heroin continually, and when they would do anything to get heroin, even if that meant selling everything in the house. A local expert in the Kachin state informed the Washington Post that “every home contains an addict” and shared her experience of her husband and child selling everything in the house to buy heroin (The Burmese do so much heroin that syringes are used for currency, 2021).

Like recovered addicts from church, many addicts in the region want to escape their addictions and turn their lives around. The youtube video Al Jazeera English shows that addicts are aware of their situation and desperately wish to turn it around. However, they do not know if they will overcome their addiction. Religious church groups focus on rehabilitation for drug addicts, providing them with shelter, food, and necessities in return for a promise to stay clear of heroin. Some of the recovered addicts managed to turn their lives around and live to tell their tales. Many people of ethnic minorities in Burma leave the country due to discrimination; among the refugees, the recovered addicts also escaped. In the churches years later, they testify about their times in the mines and their redemption.

Work Cited:

McCoy, Alfred W. The Politics of Heroin: CIA Complicity in the Global Drug Trade, Afghanistan, Southeast Asia, Central America, Colombia. Lawrence Hill Books, 2003.

Journeymanpictures, director. Who Is the Drug King of the Golden Triangle? (1994). YouTube, YouTube, 24 Feb. 2011, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ji2S_cGFPqc. Accessed 9 Nov. 2022.

Weimer, Daniel. Seeing Drugs: Modernization, Counterinsurgency, and U.S. Narcotics Control in the Third World, 1969-1976. Kent State University Press, 2013.

sydpost 1年 ago, Sydpost, sydpost 4月 ago, & * 名称. (n.d.). Home. The Sydney Post. Retrieved December 13, 2022, from https://au.sydpost.com/?p=1412

The Golden Triangle: Forbidden Land of Opium. Alexander Street, a ProQuest Company. (n.d.). Retrieved December 13, 2022, from https://video-alexanderstreet-com.proxyiub.uits.iu.edu/watch/the-golden-triangle-forbidden-land-of-opium

McCoy, T. (2021, October 26). The Burmese do so much heroin that syringes are used for currency. The Washington Post. Retrieved December 13, 2022, from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/morning-mix/wp/2014/10/30/the-burmese-do-so-much-heroin-that-syringes-are-used-for-currency/

Unaids.org. (2020, March 23). Mining, drugs and conflict are stretching the AIDS response in northern Myanmar. UNAIDS. Retrieved December 13, 2022, from https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/presscentre/featurestories/2020/march/20200323_myanmar

AlJazeeraEnglish. (2013, December 29). Myanmar youth grapple with Heroin Addiction. YouTube. Retrieved December 13, 2022, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Iz4snOu_has

PBSNewsHour. (2014, December 11). Myanmar’s jade miners suffer rampant heroin addiction. YouTube. Retrieved December 13, 2022, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JtETRWtpfC8