3 The Role of Women

The Ottoman Imperial Harem had strict social stratification as followed through traditional Islamic law. Women of the harem practiced purdah and most never left the palace.

The Valide Sultan

The valide sultan held the most powerful position in the Ottoman Imperial Harem, more powerful than even the sultan himself in those walls. She was the mother of the sultan and was his father’s chief kadin. It was the most desirable position in the harem court and one of great political power. She was in charge of the household and its staff and even played a large role in selecting the women who would be made available to the sultan as consorts. Her quarters were often as lavish as the sultan’s himself– and always adjacent to her son’s.

Mothers in Islamic Tradition

The Ottoman Empire was under theocratical rule throughout its history. As such, the ideals and social mores placed by Muhammadic tradition were law. Islamic tradition dictates that the mother was the most honored member of a household. As such, the mother of the sultan held a vital place in the harem court. It was not commonplace for a sultan to have a legal marriage to any of his consorts, although it happened several times over the course of Ottoman history. However, legal marriage was not necessary for a woman to produce legitimate heirs as long as they were recognized by the father.

Political Power and Status

The first woman to hold the official title of valide sultan was Hürrem Sultan (pictured above), the wife of Suleiman the Magnificent. She was one of the most influential people in the Empire and was an ardent patron of education, healthcare, and religious study.[2]

The Kadins

Kadins were the legal consorts of the sultan, those who were the first to produce a male heir. This was the most sought-after position in the harem, directly under the valide sultan. Once reaching the rank of kadin, a woman was eligible to receive a host of benefits, including a government pension.[3] After the birth of a baby boy, this woman would be promoted to larger quarters and a host of servants. They were also promised more regular night visits with the sultan– something unique to this role in the harem.

When this son reached maturity– typically in his late teens– he would be sent to govern one of the Empire’s provinces. He was always accompanied by his mother, who served a similar role in her new court as the valide sultan did in the central palace. The oldest son would become sultan upon his father’s death and his mother would become the new valide sultan in most cases.

Haseki sultan

While this status was not always filled, the haseki sultan was the sultan’s primary wife or most favored consort. Being the favored wife of the most powerful man in the Ottoman Empire had its benefits, and often women who held this title had great political sway. Like the valide sultan, these women sometimes interacted with heads of state and government officials via letters on behalf of the sultan. She had great power and could sometimes fill the role of valide sultan in the absence of the sultan’s mother.

The Ikbals

An ikbal was an officially recognized consort of the sultan who had not yet borne male children. Ikbal is an Arabic word that means “fortunate” or “favored one” and typically denoted a woman who had an intimate relationship with the sultan himself. [4] There was no limit to the number of ikbals a sultan could have, unlike the kadins who typically had a limit of four. They held a strict hierarchy within themselves, with the ones who caught the sultan’s eye first (or most frequently) having a higher ranking with more social standing and more privileges. Women of this role had typically converted to Islam and as such were no longer legal slaves.

The Gözde

The gözde, was an enslaved woman or girl whose purpose in the household was the sexual gratification of the sultan. These women were the quintessential “Ottoman concubine” and had far fewer rights than the women above them in the harem hierarchy. The contemporary understanding of Islamic law only allowed sexual slavery in warfare or non-Muslim land.[5] Low-ranking gözde were known as cariyes and also served as servants to the valide sultan and her children.

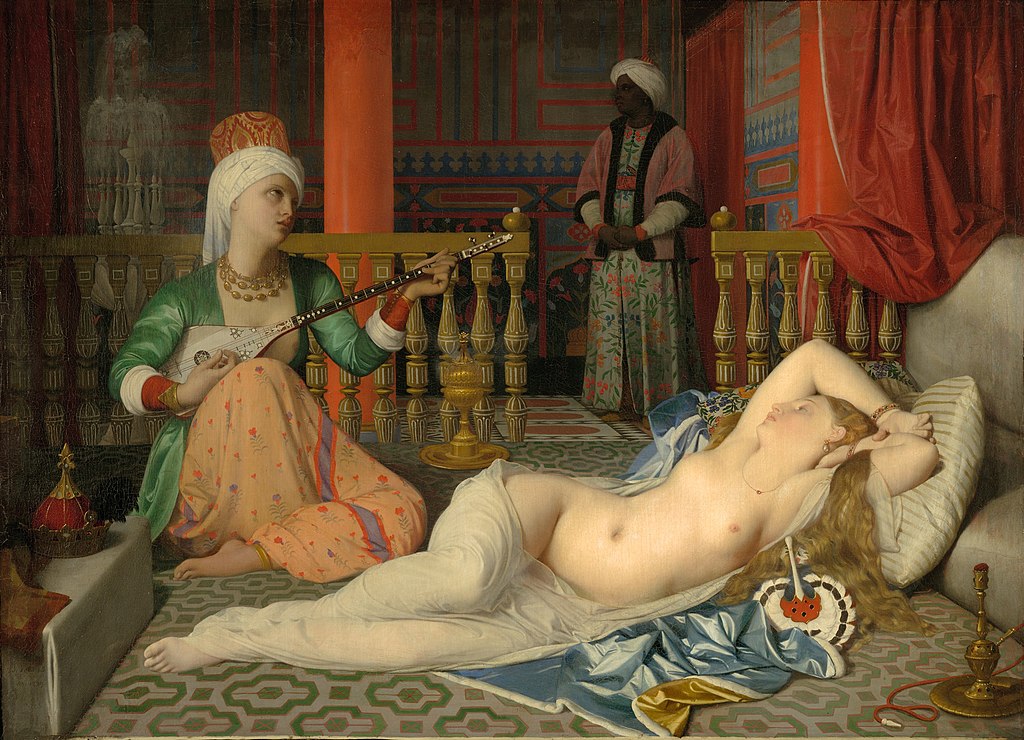

The Odalisques

The odalisque was not a woman or girl sexually available to the sultan; rather, she was an attendant to one of the ladies of the court. They were slaves of the lowest ranking, who may eventually elevate in rank with education and training. Despite the fact that odalisques had little to no interaction with the sultan (or any man not a eunuch, for that matter) the odalisques became a topic of constant fascination for Orientalist paintings. These women were often depicted in a highly erotic manner for Western consumption.

- Right n. 22: The right of the mother. Al. (2013, February 2). Retrieved December 4, 2021, from https://www.al-islam.org/a-divine-perspective-on-rights-a-commentary-of-imam-sajjads-treatise-of-rights/right-n-22-right. ↵

- Peirce, L. P. (2010). The Imperial Harem: Women and Sovereignitiy in the Ottoman empire. Oxford University Press. ↵

- Davis, F. (1986). The Ottoman lady a social history from 1718 to 1918. Greenwood Press. ↵

- Argit, Betül Ipsirli (October 29, 2020). Life after the Harem: Female Palace Slaves, Patronage and the Imperial Ottoman Court. Cambridge University Press ↵

- Madeline Zilfi: Women and Slavery in the Late Ottoman Empire: The Design of Difference ↵