Standards

Overview of Accounting Fundamentals

The below standards contain information about accounting fundamentals at Indiana University. These standards are intended to provide an understanding of commonly used accounting terminology at IU, the definition of normal balances, how balances are recorded, and how transactions are supported at Indiana University. This information will serve as the foundation for subsequent sections within this book.

Accounting Terminology is necessary to understand as it aids in interpreting transactions within the accounting function and helps to ensure accuracy of financial information.

Normal Balances are the expected balance type in the object code (debit/credit). This determines whether the account value should be increased or decreased with a debit/credit entry. Understanding the normal balance of the object code is necessary when evaluating financial statements.

Financial Transaction Substantiation refers to detailed original source documentation and/or work papers that support financial transactions showing why and how a transaction was completed. Substantiating financial transactions ensures the integrity of an entity’s financial reports and is an important tool for account management and for the preparation of external audits.

The standards listed below are related to Indiana University functions solely and are not applicable for Indiana University Foundation.

UCO-AFO-1.00: Accounting Terminology

Prerequisites

Prior to reading this standard on accounting terminology, it is beneficial to review the below standards to gain foundational information:

Preface

Accounting is an area with many unfamiliar terms.

These terms can be confusing and misleading when you do not know their meaning, understand how they relate to your entity as a whole, or why they are relevant to your day-to-day work.

This standard within the IU accounting standards book is a compilation of common accounting terms that are the basis of how and why users record financial transactions the way they do at Indiana University. Additional accounting terms can be found in the glossary.

Accounting Terminology

Double-Entry Accounting

Double-entry accounting is a method used to balance an entity’s accounts by ensuring that transactions are recorded in at least two object codes on an entity’s books. Each transaction entry must have a corresponding entry and the two must equal one another. This is often called double-entry accounting or balancing an account. This accounting method ensures that the entity’s assets = liabilities + stockholders’ equity. Examples of double-entry accounting are shown below:

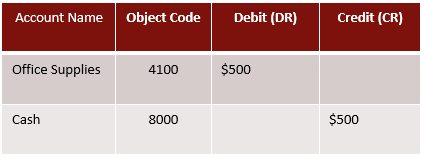

- Office supplies were purchased for $500 in cash. In this example, our office supplies expense increased by $500, and our cash decreased by $500.

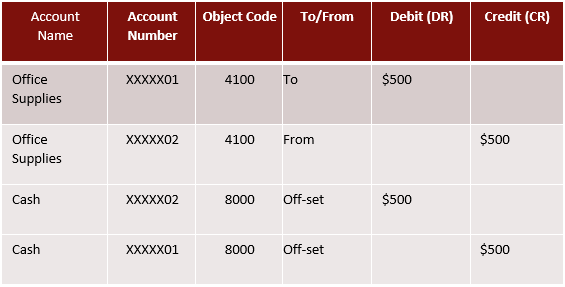

- An office supply expense for $500 was incorrectly recorded to the wrong account. An adjusting entry is required to move the expense to the correct account. A Distribution of Income and Expense (DI) or General Accounting Adjustment (GEC) document is created to move the expense, and in the process, an offset to cash is automatically created.

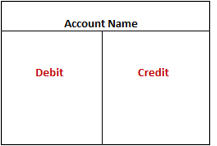

T-Account

This is a tool used to help identify the ending balance of a given asset, liability, revenue, or expense. The T-account helps organize and summarize the total transactions in an individual account. Shown most commonly as one horizontal line and a vertical line intersecting, the left side is for debits and the right side is for credits.

Debit

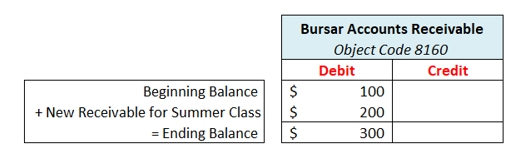

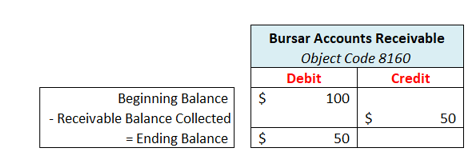

One part of double-entry accounting, a debit, is located the left side of a T-account. In accounting terms, to debit an account means to place the dollar amount assigned to a transaction on the left side of the T-account. It can either increase or decrease an object code balance, depending on the financial transaction being recorded. See the UCO-AFO-1.01 Normal Balances Standard for further detail on how debits increase/decrease different object codes. An example of debiting a T-account is shown below.

A student enrolled in a summer class for $200 creates a new bursar receivable balance. The bursar accounts receivable balance will be debited by $200, showing an increase in the asset balance.

Credit

One part of double-entry accounting, a credit, is the right side of a T-account. In accounting terms, to credit an account means to place the dollar amount assigned to a transaction on the right side of the T-account. It can either increase or decrease an object code balance, depending on the financial transaction being recorded. See the UCO-AFO-1.01 Normal Balances Standard for further detail on how debits increase/decrease different object codes. Using the T-account, an example of crediting an account is shown below.

A $50 outstanding bursar receivable balance was collected; the bursar accounts receivable balance will be credited by $50, showing a decrease in the asset balance.

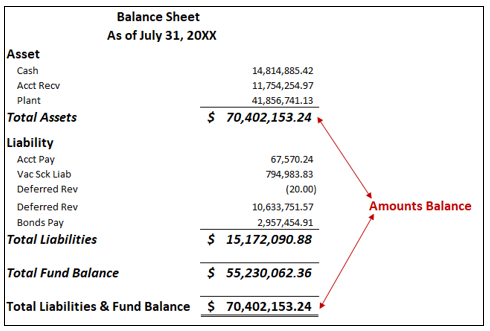

The Accounting Equation

Considered the foundation of double-entry accounting, the accounting equation states that the entity’s balance sheet must balance. This is calculated using the equation below.

Assets= Liabilities + Equity*

*Note: At IU, equity is the equivalent of fund balance

See the below example for visual representation of the accounting equation, which shows how the balance sheet should balance.

Journal Entry

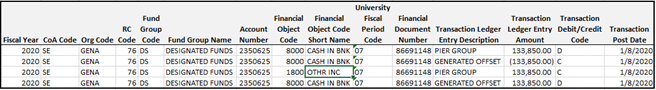

Journal entries are records of business transactions. A business transaction is the exchange of goods or services for a form of payment. A journal entry is used to record each transaction and include more information about the transaction such as the date, amount, description of the entry, and a unique reference number, often called a journal entry number. An example journal entry recorded in IU’s KFS is included below.

General Ledger

The general ledger (GL) is a master document that records all transactions generated at IU. With each transaction, account values on the general ledger are increased or decreased depending on the transaction. The general ledger is organized into accounts: assets, liabilities, fund balance, revenues, and expenses. Every financial transaction or journal entry created by a unit generates an accounting transaction which is then recorded in the general ledger. Overall, the general ledger helps management prepare accurate and organized financial statements. Further information about the general ledger can be found in the General Ledger Standards. Refer to the Fiscal Officer Reporting Tools for the general ledger detail report.

Chart of Accounts

The chart of accounts is an organizational structure for the entire university for all accounting, reporting, and budgeting. The structure is built using chart codes, responsibility centers, organizations, accounts, object codes, and other chart of account components. Within IU, chart of accounts is commonly referred to as COA. Further information on the chart of accounts structure and its components can be found in the Chart of Accounts Standards.

Financial Statements

The financial statements are a collection of reports that summarize IU’s financial activity, position, and cash flow for the year. The financial statements help users determine IU’s ability to generate cash, how much debt the university holds, and how profitable IU is both currently and historically. At IU, the financial statements include: the balance sheet, income statement, and statement of cash flows, along with any accompanying notes. For further information on the financial statements, refer to the Financial Statements Standards.

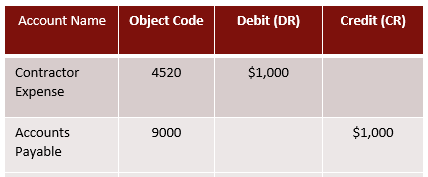

Accrual Accounting

Accrual accounting is a method that records revenue when it is earned and records expense when it is incurred, not when the cash is received. Different than cash accounting, this method provides a more realistic understanding of income and expense and helps with long term projections. An example of accrual accounting is presented below.

An invoice for $1,000 was received for work performed in May 20XX by IU in July 20XX, after fiscal year-end. An accrual for the total amount of the invoice should be recorded prior to fiscal year-end close as the service was provided in the current fiscal year. The entry for this accrual would be:

Accounting Principles

Accounting principles are general rules and guidelines that entities must follow to accurately report their financial statements. There are five key principles that all accountants and entities must follow to accurately record their financials: revenue recognition, historical cost, objectivity, matching, and full disclosure. These are requirements set by the Accounting Governing Board in the United States and are critical concepts to understand prior to recording entries and creating financial statements. Refer to the Accounting Principles standard for further detail.

Fund Accounting

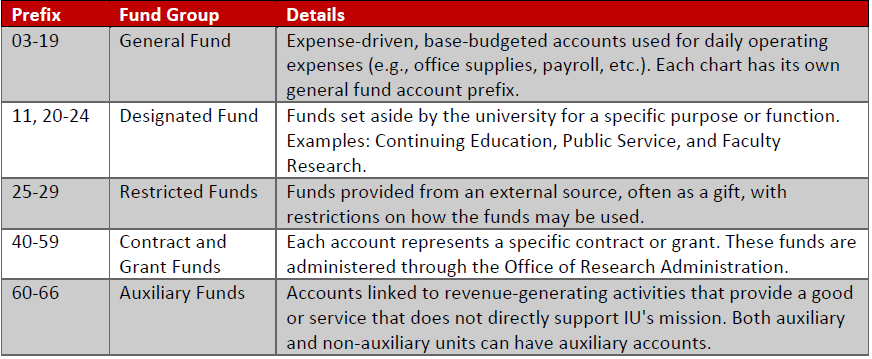

Specific to federal, state, local government, and those organizations that are funded by a government, fund accounting segregates resources based on restrictions and/or specifications from the funding organization. At IU, these segregations are called fund groups. Fund accounting is an important concept that has an impact on external financial statement presentation and internal decision-making by IU’s top executives. Indiana University is a proprietary fund of the State of Indiana, but within the university’s accounting, fund groups are broken out as follows:

For more information on IU specific fund accounts, please refer to the UCO-COA-1.02 Fund and Sub-Fund Groups Standard. To show the impact of fund accounting at IU, the below example walks through a typical entry for an auxiliary unit.

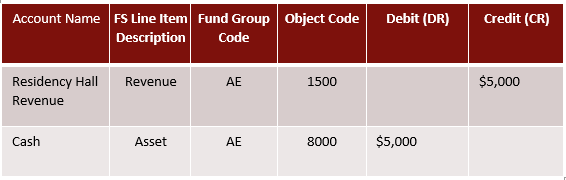

An incoming undergraduate student has signed up to live in a residence hall on campus the fall semester. Prior to the student’s arrival, they pay their residence hall fee of $5,000. To record this transaction to the auxiliary fund and correct object codes, the IU employee processing the account activity would create the below entry.

US Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (US GAAP)

US GAAP is the combination of authoritative standards (requirements) and the commonly accepted ways of recording and reporting accounting information. US GAAP is issued by the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB), the organization responsible for establishing accounting and financial reporting standards for companies and nonprofit organizations in the United States.

Government Accounting Standards Board (GASB)

GASB is similar to the FASB, but issues generally accepted accounting principles for state and local governments and those entities that are funded by state and local government. Indiana University is a component of the State of Indiana, meaning IU falls under the umbrella of the state and is a government funded organization. As such, IU is required to follow all GASB standards along with US GAAP.

Requirements and Best Practices

This portion of the standard outlines general requirements and best practices related to accounting terminology. While not required, the best practices outlined below allows users to gain a better picture of the entity’s financial health and help identify potential issues on a more frequent basis. This allows organizations to identify errors, mistakes, and pitfalls which can be remedied quickly and prevent larger issues in the future.

Requirements

- Review the accounting terminology standard in full and the accounting glossary to gain pertinent knowledge of accounting at IU. After reviewing, if users have questions, reach out to the campus office or the Accounting and Reporting Services team at uars@iu.edu.

UCO-AFO-1.01: Normal Balances

Prerequisites

Prior to reading the normal balances standard, it is beneficial to review the below standards to gain foundational information:

- Roles and Responsibilities Standards

- UCO-AFO-1.00 Accounting Terminology Standard

- UCO-AFO-2.00 Accounting Principles Standard

Preface

This standard discusses fundamental concepts as they relate to recordkeeping for accounting and how transactions are recorded internally within Indiana University. Information presented below walks through specific accounting terminology, debits and credits, as well as what are considered normal balances for IU.

Introduction to Normal Balances

What are Debits and Credits?

Entities make financial transactions on a day-to-day basis in order to continue running business operations. When accounting for these transactions, two entries must be made: a debit and a corresponding credit.

Debits and credits are what make up journal entries in a general ledger. Debits and credits either increase or decrease the following accounts: asset, liability, fund balance, revenue, or expense. The following chart shows the direction of debits and credits in various accounts as well as each account’s normal balance.

| Account | Normal Balance | To Increase | To Decrease |

| Assets | Debit | Debit | Credit |

| Liabilities | Credit | Credit | Debit |

| Stockholders’ Equity | Credit | Credit | Debit |

| Revenues | Credit | Credit | Debit |

| Expenses | Debit | Debit | Credit |

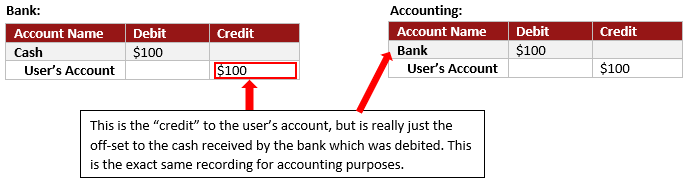

Debits and credits differ in accounting in comparison to what bank users most commonly see. For example, when making a transaction at a bank, a user depositing a $100 check would be crediting, or increasing, the balance in the account. But for accounting purposes, this would be considered a debit. While the two might seem opposite, they are quite similar. Breaking down the above example of depositing a $100 check from both perspectives – banking and accounting, users can see that, while it appears as a “credit” to the user depositing the check, it is really just the bank’s off-set to the receipt of the check.

What are Normal Balances?

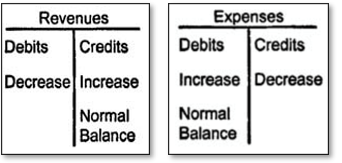

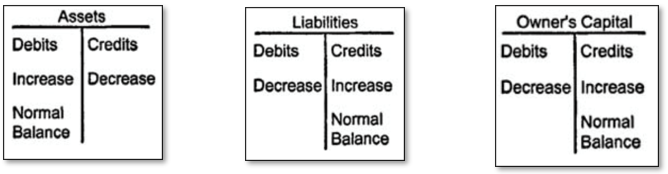

To better visualize debits and credits in various financial statement line items, T-Accounts are commonly used. Debits are presented on the left-hand side of the T-account, whereas credits are presented on the right. Included below are the main financial statement line items presented as T-accounts, showing their normal balances.

Income Statement T-Accounts:

A normal balance is the side of the T-account where the balance is normally found. When an amount is accounted for on its normal balance side, it increases that account. On the contrary, when an amount is accounted for on the opposite side of its normal balance, it decreases that amount.

Balance Sheet T-Accounts:

Within IU’s KFS, debits and credits can sometimes be referred to as “to” and “from” accounts. These accounts, like debits and credits, increase and decrease revenue, expense, asset, liability, and net asset accounts.

Debit and Credit Examples

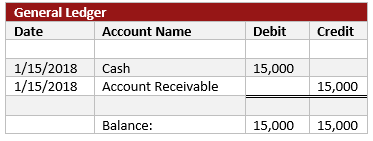

Below is a basic example of a debit and credit journal entry within a general ledger.

This general ledger example shows a journal entry being made for the collection of an account receivable. Because both accounts are asset accounts, debiting the cash account $15,000 is going to increase the cash balance and crediting the accounts receivable account is going to decrease the account balance. When we sum the account balances, we find that the debits equal the credits, ensuring that we have accounted for them correctly.

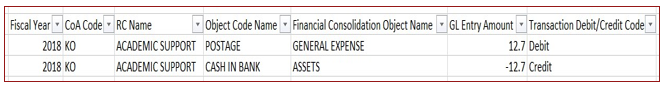

To show how the debit and credit process works within IU’s general ledger, the following image was pulled from the IUIE database. Employees who are responsible for their entity’s accounting activities will see a file such as the one below on more of a day-to-day basis. This general ledger example shows a journal entry being made for the payment (cash) of postage (expense) within the Academic Support responsibility center (RC).

This transaction will require a journal entry that includes an expense account and a cash account. Note, for this example, an automatic off-set entry will be posted to cash and IU users are not able to post directly to any of the cash object codes. Because postage was purchased for $12.70, cash, an asset account, will be credited, which will decrease the cash balance by $12.70. Contrarily, purchasing postage is an expense, and therefore, will be debited, which will increase the expense balance by $12.70. When the account balances are summed, the debits equal the credits, ensuring that the Academic Support RC has accounted for this transaction correctly.

Requirements and Best Practices

This portion of the standard outlines requirements and best practices related to normal balances. While not required, the best practices outlined below allows users to gain a better picture of the entity’s financial health and help identify potential issues on a more frequent basis. This allows organizations to identify errors, mistakes, and pitfalls which can be remedied quickly and prevent larger issues in the future.

Requirements

- Review the normal balances standard in full to gain pertinent knowledge of accounting at IU. After reviewing, if users have questions, reach out to the campus office or the Accounting and Reporting Services team at uars@iu.edu.

UCO-AFO-1.02: Financial Transaction Substantiation

Prerequisites

Prior to reading the standard on material transaction substantiation, it is beneficial to review the below standards to gain foundational information:

Preface

This standard discusses the elements of the financial transaction substantiation process and how it is conducted internally within Indiana University. Information presented below will outline requirements for transaction support, documentation required to substantiate a transaction, and requirements and best practices related to this process.

Introduction

Transaction substantiation is key to ensuring the accuracy of the university financial statements and compliance with external regulatory requirements. Transaction substantiation at IU refers to detailed original source documentation and/or work papers that support financial transactions. The supporting documentation or substantiation should be detailed enough that a person without extensive knowledge of the transaction can review the support, understand the nature of the transaction, and tie it back to the general ledger detail. Auditors request documentation that supports financial transactions showing why and how a transaction was completed in order to ensure accuracy, completeness, and compliance with all local, state, and federal requirements. In order to ensure all fiscal officers and transaction initiators are familiar with the requirements for financial transaction substantiation, examples of appropriate support to provide are discussed below.

Importance and Impact of Financial Transaction Substantiation

Substantiating financial transactions is an important tool for account management and preparation for external audits. Reviewing financial transactions helps identify transaction errors, inaccurate balances, improper spending, embezzlement, and highlights other negative activity, such as theft or fraud, before balances are finalized for a period-end close. Failure to detect these errors may lead to issues concerning internal controls or the accuracy of the financial statements which impacts future funding from government organizations, creditors, or donors.

In order to ensure the integrity of an entity’s financial reports, it is important that each entity substantiate financial transactions at the time they are initiated and review material transactions on a quarterly basis. By substantiating transactions at the time of entry and reviewing on a quarterly basis, the university can produce reliable and accurate financial statements free from material misstatement that could result in false conclusions. This is important for the university’s externally audited consolidated financial statements as well as internal management reporting for decision making.

Substantiating Financial Transactions

Documentation is a critical aspect of substantiating financial transactions. To meet the transaction substantiation requirements, documentation should stand alone in answering the questions of: Who, What, Where, When, and Why?

Properly identifying and substantiating transactions involves:

- Determining and gathering the appropriate supporting documentation (i.e. contracts, written agreements, schedules, and invoices) for each transaction

- Ensuring transactions are substantiated, supported, and answer all of the who, what, where, when, and why questions

- Having the documentation readily available for audit or other purposes

Transaction Substantiation Process

Every financial transaction at Indiana University is required to have substantiation. Examples of types of transactions that need to be substantiated include accounts receivable, accounts payable, contract and grants, unearned revenue, and state appropriations. Standard procedures should be in place to ensure entities are reviewing transactions and maintaining the appropriate documentation according to the schedule for financial records in the university document retention policy. The substantiation process at the account line-item level typically comprises the following steps:

- Identify the transaction that needs to be substantiated. It is the responsibility of the document initiator to provide and maintain document substantiation.

- Gather appropriate documentation. Each transaction is required to have the following:

- A copy of the original source document such as an agreement, contract or grant documentation, analysis conducted, calculations completed, emails, memos, receipts, etc. that supports the transaction.

- The KFS document number (i.e, invoice, cash receipt, ACH).

- An appropriate storage index which is retrievable by KFS document and date in the event of an audit. Fiscal officers are responsible for ensuring that substantiation is maintained for their accounts. Below are examples of Who, What, When, Where, and Why questions as it relates to documentation:

-

- Who: Who completed the transaction and was involved in the transaction? What parties? Anyone outside of IU?

- What: What was the reason for the transaction?

- Where: Where did the transaction originate from if not KFS? Was it from an outside system?

- When: When did the activity that caused the transaction take place? For example, when were services provided or items purchased? Is the activity taking place over multiple reporting periods or fiscal years?

- Why: Why was the entry booked the way it was? For example, was there a specific methodology or calculation completed to support the transaction amount. The detailed calculation should accompany the documentation. Why was this account and object code used? It should be evident from the documentation why a particular account and object code were used.

Requirements and Best Practices

This section outlines general requirements and best practices related to transaction substantiation. Following the requirements and best practices outlined below will help to avoid audit errors, financial misstatements, fraud, and allow users to gain a better understanding of their entity’s financial health.

Requirements

- Every financial transaction at Indiana University is required to have substantiation.

- The fiscal officer is responsible for having all financial transaction substantiation available for audit and other purposes.

- The fiscal officer is responsible for the accuracy, reliability, and completeness of all financial transactions on their account.

Best Practices

- Compile the transaction substantiation at the time the transaction is initiated.

- Review financial transactions on a monthly basis and have the required substantiation on file for review.

- Prior to approving any document, validate the transaction by reviewing supporting documentation to verify the transaction is necessary and appropriate.

A Proprietary Fund is used in governmental accounting to account for business-type activities that are financed in whole or in part by fees charged to external parties for goods or services.

A tool used to help identify the ending balance of a given asset, liability, revenue or expense. The left side is for debits and the right side is for credits.