Standards

Financial Statements Overview

Financial statements are used to assess an entity’s overall financial health. Internal and external users (i.e., suppliers, creditors, state, and federal agencies) depend on these statements to analyze the entity’s financial position and make informed decisions.

Financial information presented in the external audited financial statements may be presented differently than reports pulled internally.

However, the transactions used to create internal financial information are the same as those used to create the audited external financial statements. Therefore, it is critical that unit fiscal officers ensure that transactions are recorded correctly within their organization. For more information on the consolidated statements for IU, see the Indiana University Finance site.

The standards listed below are related to Indiana University functions solely and are not applicable for Indiana University Foundation.

UCO-AFO-3.00: Internal and External Financial Statements

Prerequisites

Prior to reading the Internal and External Financial Statements standard, it is beneficial to review the below standards to gain foundational information:

- Accounting Fundamentals Standards

- Chart of Accounts and General Ledger Standards

- Financial Statements Standards

Preface

This standard discusses the differences between the internal and external financial statements for Indiana University.

The University internal financial statements that are published in the Controller’s Office Reporting Tools serve as the university’s official standard internal reports for actual financial results (e.g., not budgeted results). Information presented below will walk through a general understanding of the internal vs. external financial statements along with executive level presentation requirements specifically related to IU reporting. It will also specify requirements and best practices for users of the financial statements.

Introduction

What are Financial Statements?

Financial statements are reports which show the financial condition and performance of the university. They are used to assess an entity’s overall financial health. Internal and external users (i.e., suppliers, creditors, state, and federal agencies) depend on these statements to analyze the entity’s financial position and make informed decisions.

Financial information presented in the external audited financial statements may be presented differently than reports pulled internally. However, the transactions used to create internal financial information are the same as those used to create the audited external financial statements. Transactions booked by departments feed into the external financial statements, the accuracy of the external financial statements is dependent on the accurate recording of those transactions.

The Office of the University Controller is responsible for management of the Controller’s Office Reporting Tools which are utilized by internal users. However, fiscal officers are responsible for any modifications made to such reports and providing explanations for differences as discussed above.

External Financial Statements

External financial statements are used to provide financial reports that aid external users in decision making and to satisfy compliance requirements of external parties. Users of external financial statements include, but are not limited to, government agencies, bond rating agencies, accrediting agencies, suppliers, creditors, and other interested parties external to the university. The primary difference between the external and internal financial statements is that external statements are governed by external regulations.

- External financial reporting should adhere to all required accounting pronouncements, standards, rules, and or other regulations stipulated General Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP), Governmental Accounting Standards Board (GASB), and other applicable standards.

- External financial reporting should reconcile to internal reporting utilizing the same underlying transactions.

- External financial statements are subject to audit under federal and state law.

University Internal Financial Statements

University internal financial statements are used to provide financial reports that aid internal users in decision making. Users of internal financial statements include, internal groups including executive leadership, campus/department/division/school leadership, and any party internal to the university.

- University internal financial statements under the Office of the University Controller are the official internal statements of campus and unit-level activities.

- Internal financial reporting may differ in format, level of detail, or include only subsets of financial data, but should always reconcile to external financial reporting utilizing the same underlying transactions.

- Internal financial reporting which contains differences to external financial reporting in substance or format should be accompanied with a variance analysis explaining the differences prior to publication of internal financial reporting to any internal or external audience.

- Internal financial data is the underlying data for external financial reporting and is subject to audit under federal and state law and other external agencies.

Requirements and Best Practices

Requirements

- The University Internal Financial Statements are required to be used for all closing activities. These financial statements can be found in the Controller’s Office Reporting Tools.

- It is the expectation of the Board of Trustees, executive leadership, auditors, and external regulatory bodies that actual internal financial results tie to the University Internal Financial Statements. Actual internal financial results that do not tie must be reconciled, disclosed as such, and contain appropriate explanations.

Best Practices

- University Internal Financial Statements run in the Controller’s Office Reporting Tools are the official financial statements for the university and should be used for financial decisions.

UCO-AFO-3.01: Income Statement

Prerequisites

Prior to reading the Income Statement standard, it is beneficial to review the below standards to gain foundational information:

- Accounting Fundamentals Standards

- Chart of Accounts and General Ledger Standards

- UCO-AFO-3.02 Balance Sheet Standard

Preface

This standard discusses what makes up the income statement and how it is used internally within Indiana University. Information presented below will walk through a general understanding of the income statement, presentation requirements specifically related to IU reporting, and lastly, will specify requirements and best practices for users of the financial statements. For further information on how to pull the income statement or any of the referenced reports within requirements and best practices, refer to the Financial Statement Reports instructions.

Introduction

What is an Income Statement?

The income statement, also known as the statement of revenues, expenses, and changes in net position, summarizes an entity’s revenue streams, expense categories, and overall profitability. The main purpose of this financial report is to measure the financial performance of the entity by comparing the revenue earned and the expenses incurred during the period. The net of the revenue and expenses is considered the net income and shows the overall financial health of the entity for a period of time (i.e., fiscal year, quarter, month). The net income is carried forward to the balance sheet as part of the fund balance.

An income statement is one of the three main financial statements, along with the balance sheet and cash flow statement. It represents the inflow (revenue) and outflow (expense) of resources the entity accumulates in a given period, most typically, a fiscal year.

How is the Income Statement Organized?

The income statement is made up of multiple types of revenue and expense balances; see below for further explanation of common revenue and expense types. The income statement is based on the equation Revenues – Expenses = Net Income, commonly referred to as net position. If the net balance of revenue and expenses is positive, it is referred to as net income; if the balance is negative, it is referred to as a net loss.

Income statements list revenues first. Within Indiana University, revenue object codes have a range from 0001 – 1999. Transfer In object codes may not fall within this range because they have pre-determined mapping within the system. For further detail on this, refer to the Summary of Transfer Object Codes document.

Expenses are listed after revenue. Common examples of expenses include salary and wages, supplies and expense, computing services, and contractual services. Expense related object codes have a range from 2000 – 7999 within Indiana University. Not all object codes are available for departments to use. Allotments and charges out plus transfers out may not fall in this range because they have predetermined mapping within the system. For further detail on this, refer to the Summary of Transfer Object Codes document.

While it is important to note some object codes may fall outside the ranges, it is also key to highlight that some object codes within the ranges may not be available for departments to use because they are either system-generated or are limited to use by either the campus, Treasury, or the Controller’s Office. If you have questions related to balances associated with system-generated or limited use object codes, on your income statement, please contact your (RC) fiscal officer or campus office.

Operating vs. Non-Operating

Both revenues and expenses are designated/classified as operating and non-operating.

- Operating revenues and expenses are defined as revenues and expenses associated with day-to-day operations of a business. These amounts are typically used to analyze the financial health of the organization and determine future cash needs. Operating margin is operating revenues less any operating expenses.

- Non-operating revenues and expenses are defined as amounts that have been incurred outside of the entity’s day-to-day activity. Common examples include gift revenue, gains/losses, and interest income. These revenues and expenses are accounted for separately to better analyze the performance of the core business and ignore outside factors. Non-operating margin is the difference between the non-operating revenues and expenses.

Indiana University presents the income statement at the operating and non-operating level to provide a further level of detail for external users.

The income statement in the Controller’s Officer Reporting Tools presents revenue and expense information differently in order to align to internal user’s needs. Users have the ability to set parameters based on the required level of detail (i.e., object code, object level, etc.). Additionally, users can select a parameter to exclude transfer object codes from the operating and non-operating margins and the transfer object codes are then presented below the net income line of the income statement.

Indiana University also accounts for encumbrances which are ear-marked funds set aside to cover future anticipated expenses. Encumbrance balances are not represented on the face of the income statement.

Revenue

An organization’s revenue streams are listed first on the income statement and typically recorded as credit balances. Revenues are recognized on the income statement in the period they are earned, or when the good/service has been provided/performed for the customer. See the Accounting Fundamentals Standards and the Revenue Recognition Standards for further guidance on revenue recognition and proper recording of revenue balances.

Typically, organizations have more than one revenue stream. Examples of Indiana University’s revenue streams include:

Operating Revenue:

- Tuition and Fees – Fees collected from all students enrolled in a university class or program. Tuition revenue is split between several object codes based on student classification (full time, part time, etc.) and academic period (fall, summer, etc.). Fees associated to the student’s enrollment include activity, student health, and technology, in addition to others.

- Grants and Contracts – Funding received from the federal, state, and local governments along with private entities to further IU’s mission and provide financial support for IU’s academic endeavors. Grants and contracts typically have requirements to receive the funds such as a certain service being performed, matching requirement, etc. – this is considered restricted under IU fund accounting. This information is tracked by IU and reported back to the granting/contracting organization. There are also grants and contracts that are non-operating.

- Sales & Services Revenue– Revenue that is outside Indiana University’s general mission. Examples of auxiliary revenue at IU include ticket sales revenue, parking permit payments, and catering services.

- Other Income – Miscellaneous smaller revenue streams outside of Indiana University’s general mission. Examples of other revenue at IU include parking citations, matching fund revenue, and collections on bad accounts.

Non-operating Revenues:

- State Appropriations – funding received from the state through permanent law or an annual appropriations act. Appropriations are most commonly restricted for use in student financial aid and daily operations of the university.

- Gifts – donations received from the public, either from individuals or organizations. Typically, gifts do not require anything to receive the money, but may be earmarked for a certain purpose.

- Indirect Cost Recovery – Money received by the university as reimbursement related to the costs of implementing the project or contract. The indirect rate (% of direct costs incurred related to this project) is stipulated by the granting organization.

Expenses

An entity’s expense streams are listed after revenue on the income statement and are recorded as debit balances. Expenses are defined as the cost incurred to do business or the outflow of resources associated with the general operations of an entity. Since Indiana University operates on an accrual basis of accounting, expenses are recognized as they are incurred (i.e., when the good is received or service is performed) and should be recorded in the same fiscal period as the related revenue – this is considered the matching principle. See the Accounting Fundamentals Standards for further guidance on expense recognition and recording expense balances.

Typically, organizations have more than one expense stream. Examples of Indiana University’s expense streams include:

Operating Expense

- Compensation – Payments made to IU faculty and staff. Compensation comprises an employee’s salary along with overtime, bonus payments, time-off, and commission (if applicable). Compensation makes up IU’s largest expense.

- Benefits – Payments made on behalf of IU faculty and staff to provide additional non-cash compensation to employees. Benefits range from health and dental insurance, retirement plans, and employee assistance programs. Benefits are lumped in with compensation on IU’s income statement. Benefit expense is based on an approved pooled rate and is not charged based on direct expense. Benefit expense is automatically calculated when processing payroll – see the Payments Standards for further detail on benefit pool rates.

- Student Financial Aid – All scholarship awards IU has provided to its students. IU provides various financial aid packages to students to encourage qualified students to attend who otherwise may not.

- Travel – Expenses associated with traveling for IU business related activities which can include transportation and lodging expenses.

- Supplies and General Expense – Expenses to supply employees’ items required for daily job function. Supplies can range from janitorial items to desk supplies, light bulbs, and uniforms. These expenses are unrelated to the entity’s mission as they do not have a direct impact on the goods or services IU provides to its customers.

- Cost of Goods Sold (COGS) – Costs incurred to maintain IU’s normal operating expenses. These costs are used to fulfill goods and services IU has agreed to provide. This expense code is most frequently used in auxiliary units. Common examples of expenses included in COGS are cost of materials, inventory costs, and direct labor.

- Depreciation Expense – The allocation of the cost of a capital asset expensed over the expected life “useful life” of the asset. This is a monthly recurring expense that as has no cash impact.

Non-Operating Expense:

- Interest expense – Interest payments made on existing debt such us lines of credit, loans, etc. External debt and related expenses are typically handled by the Office of the Treasurer.

Net Income

Net income is the difference between revenues and expenses on the income statement. In general, it is the amount left over after all expenses have been subtracted from cumulative revenue streams. Net position is typically looked at on a historical and comparative basis by comparing numerous fiscal years to one another. Changes in net position are a representation in improvement or decline of the entity’s overall financial health.

Income Statement Presentation

Since the income statement shows financial activity over a given fiscal period, internal management and external users can use this information to compare one fiscal period to the next. In order to truly recognize patterns and trends, users are encouraged to review multiple fiscal years from the Controller’s Office Reporting Tools.

As an additional function available on the income statement, the budget column is included for comparative purposes. Currently, the report logic is based on a hierarchy where it looks at adjusted/base budget (BB) first, then current budget (CB), and lastly monthly budgets (MB) which are defined below.

| Type of Budget | Description |

|---|---|

| Adjusted Base Budget (BB) | The adjusted base budget is defined as the initial July 1 budget load adjusted throughout the year through the use of base budget adjustments. The adjusted base budget is the basis for budget construction for the upcoming fiscal year. |

| Current Budget (CB) | The current budget is loaded along with the base budget load on July 1 and reflects any budget adjustments to the current year only. Common examples include: 1. A one-time expense, 2. A prorated amount in the current year. For example, a budgeted position was vacant and filled as of January 1. For the current fiscal year, you would only need 6 months of salary and would realize 6 months of savings which could be moved through a current budget adjustment and utilized elsewhere to cover expense. |

| Monthly Budget (MB) | Monthly budgets allow departments to spread their annual budget into 12 different buckets. This is important when entities have revenue and expense lines that are not earned or incurred evenly over the 12 months of the fiscal year. This may include: 1. (Fall) tuition revenue- earned August/September and utilized through December, 2. Academic 10 month salaries- paid August through May, 3. Cyclical auxiliary activity – football ticket revenue is typically earned from September-November. |

Within the financial statement reports, the budget column displays the current or monthly budgets compared to actuals. Currently, the monthly budgets allow departments to spread their annual budget into 12 different buckets. If users do not utilize the monthly budget function and adjust, then the budget is spread evenly across the remaining open periods. UCO is currently evaluating including other budget options within the financial statement reports for those units who do not complete monthly budgets.

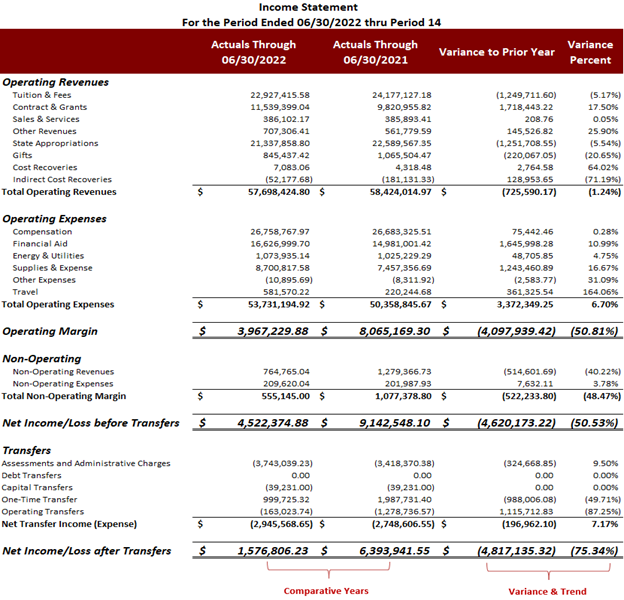

To gain better insight on the financial statement reports, below is an income statement extract which can be pulled from IU’s internal reporting site, Controllers Office Reporting Tools. It highlights two comparative periods’ revenues, expenses, and net incomes with transfer codes excluded and displayed below the Net Income line. For further information on how to pull an income statement, see the Financial Statement Reports instructions.

Requirements and Best Practices

The above paragraphs provide users with a better understanding of the purpose of the income statement along with what is included and how the income statement is formatted for IU internal reporting. The following information will discuss how to interpret the income statement and procedures all users need to follow when pulling the income statement report. By pulling the income statement on a regular basis, users are able to ensure an entity’s financial health. It is important that each entity monitors and analyzes their income statement on, at least, a quarterly basis. This allows organizations to identify errors, mistakes, and pitfalls which can be remedied quickly and prevent larger issues in the future.

Requirements

The (RC) fiscal officer is responsible for the accuracy, reliability, and completeness of the income statement.

Quarterly Activities

- Run the income statement at least quarterly with comparative balances. Please refer to Financial Statement Reports instructions for more information.

- Complete a variance analysis for all operating accounts on a quarterly basis. As part of this process, organizational units need to be able to provide explanations of material variances to UCO upon request only. Please check with your campus and/or RC, as they may require variance analysis submission on a quarterly or annual basis. Please see the UCO-CLS-3.00

Variance Analysis Standard for more information. - Users must make this supporting documentation for the entity’s income statement available upon request for audit or other purposes. Documentation should be maintained for all non-system-generated transactions. For further information see the UCO-AFO-1.02 Financial Transaction Substantiation Standard.

Annual Activities

- Run the income statement as of year-end and review for the below information:

- Negative balances on the income statement that are prior to year-end. Analysis should be done to further evaluate if any adjustments are necessary. For instructions on how to run this report, please see the Account Negative Balance Report instructions.

- Complete a detailed variance analysis for all operating accounts. Variances should be analyzed based on specific thresholds for the current fiscal year. Refer to the Closing Checklist for those thresholds.

Best Practices

- Review the income statement monthly and consider the below checklist of questions. The (RC) fiscal officer is responsible for reviewing and analyzing the operational needs of the RC/organization. Analyzing the income statement allows the fiscal officer to determine if revenues are exceeding expenses to ensure profitability for the period. The questions that need to be asked will vary depending on the needs; however, the following questions are some common examples:

- Are you operating at a profit or a loss? This analysis can help future budgeting and determine areas of surplus or areas that spending needs to be cut.

- What is your contribution margin (sales minus variable costs) and how does it compare to prior periods’ contribution margins? An entity’s contribution margin should generally be increasing from period to period.

- Are there certain expenses or revenues that are significantly over/under budget? If an entity is over or under budget on a line item, that may have a large impact not only on that specific entity, but throughout IU.

- Are all non-cash items included and booked at period end? By ensuring all non-cash transactions such as accruals, transfers, and manual entries, are reported, entities are correctly reporting their ending net position and not artificially inflating/deflating ending balances.

- Does the entities cash position meet operational needs – is the entity working on a surplus or deficit? Discuss within your department to determine if resources are being used correctly and/or if any changes in spending should be considered. Additionally, just because you have a positive net income doesn’t mean the entity has enough cash.

- Are expenses properly matched to revenues? Expenses should be accounted for in the same period as revenue is received, no matter when the cash changes hands.

- Evaluate the department’s financial trends for 3-10 years and determine if there are any predictable patterns that may impact future periods. It is difficult to evaluate overall performance by comparing current activity to the prior year only, so performing trend analysis will be beneficial to determine potential issues that could impact the future.

- Review select financial ratios as noted in the standard procedures and ensure calculations are in-line with IU’s policies and requirements. Refer to the Financial Ratios document for more information on ratios.

- Contribution Margin Ratio

- Gross Margin Ratio

- Compare and analyze current year to budget or prior year balances helps assess the entity’s profitability and ensure that enough funding is received to cover costs.

- When reviewing, make sure that all account balances align with either the expense or revenue normal balance for the specific account. This helps to ensure correct balances and eliminate potential errors when reviewing the Account Negative Balance Report.

UCO-AFO-3.02: Balance Sheet

Prerequisite

Prior to reading the Balance Sheet standard, it is beneficial to review the below standards to gain foundational information:

Preface

This standard discusses what makes up the balance sheet and how it is used internally within Indiana University. Information presented below will walk through a general understanding of the balance sheet, presentation requirements specifically related to IU reporting, and lastly, will specify requirements and best practices for users of the financial statements. For further information on how to pull the balance sheet or any of the referenced reports in the requirements and best practices portion of this standard, refer to the Financial Statement Reports instructions.

Introduction

What is a Balance Sheet?

A balance sheet, also known as the statement of financial position, is a financial statement that reflects the overall financial position of an organization at a specific period in time. It represents the resources of the entity as of a specified date – think of it like taking a picture, it is fixed once it is taken.

A balance sheet is one of the three main financial statements, along with the income statement and cash flow statement. It summarizes an entity’s assets (what it owns), liabilities (what it owes), and fund balance (its overall net worth).

How is the Balance Sheet Organized?

The balance sheet is made up multiple aggregations of transactions, referred to as balances. These balances are then presented as assets, liabilities, and fund balances and presented in order of liquidity (how quickly it can be converted to cash). The balance sheet is based on the equation; Assets = Liabilities + Fund Balance. This is commonly referred to as the accounting equation.

At Indiana University, balance sheet object codes range from 8000 – 9999 and are used to record transactions relating to assets and liabilities. Not all object codes are available for organizations to use. Certain balance sheet object codes are system-generated, and others are limited to use by either the campus or other university administrative offices (i.e., Treasury, Office of the University Controller). If a user has questions related to balances associated with system-generated or limited use object codes on the balance sheet, please contact the (RC) fiscal officer or campus office.

Assets

Assets are defined as any resource of value that can be used to generate future economic value. An organization’s assets are listed first on the balance sheet. All asset object codes, except for contra asset object codes, have a debit balance. A contra asset object code is an offset to another asset code (i.e., accounts receivable or capital assets) and typically acts as a reserve to reduce the associated asset code. Allowance object codes, such as 8950 – Allowance for Doubtful Accounts, have a credit balance.

The assets section of the balance sheet is split into current and non-current classifications.

Current Asset:

A current asset is an asset that is expected to be sold or consumed within twelve months. While each organization may have different types of current assets, common examples include:

- Cash – Currency/legal tender (i.e., paper currency or coins) that can be used in the exchange of goods or services.

- Accounts Receivable – The amount of money owed to an organization for providing a good or service. It is often shown on the financial statements net of the allowance for doubtful accounts. An allowance for doubtful accounts debt is an estimate of total accounts receivable which is not expected to be collected.

- Inventory – The products or items that an organization has on hand that are intended for resale.

- Prepaid Expenses – A payment of cash for goods or services that will be received or used at a future date. As the organization consumes the good or service or as time passes, the actual expense is recognized, and the prepaid expense is reduced. For further information on recording and recognition of prepayments refer to the Payments standards.

Non-Current Asset:

Non-current assets are long-term assets that the organization expects to hold for longer than twelve months and cannot be readily converted into cash. Each organization may hold different types of non-current assets. Common examples of non-current assets include:

- Capital Assets (Property, Plant, and Equipment) – Assets that are expected to have a useful life of more than one year and meet a certain dollar threshold. Common examples include equipment, land and buildings, vehicles etc.

- Intangible Assets – Assets that lack physical substance but have monetary or other value to the organization. These often include patents, trademarks, copyrights, computer software, logos, and easements.

Both current and non-current assets are listed in order of liquidity. As a result, cash is always listed first.

Liabilities

The second section of the balance sheet lists liabilities. A liability is a debt or obligation that arises from past events. All liability object codes, except for allowance object codes, have a credit balance. Liability allowance object codes have a debit balance. The liabilities section is also split into current and non-current classifications.

Current Liability:

A current liability is an obligation that is expected to be settled within twelve months. Common examples include:

- Salary & Wages Payable – An obligation to employees for time worked that has not been paid.

- Accounts Payable – An obligation to a supplier/vendor when an organization has received a good or service but has not yet paid for them. Accounts payable are usually recorded at their face value since the time between purchase and payment is usually short.

- Deferred Revenue – An obligation to a customer when an organization receives cash for goods or services that have not yet been provided (i.e., revenue received for a future semester’s tuition). Balances will not be recognized during the current year but will be shown as a non-current liability.

Non-Current Liability:

A non-current liability, also known as a long-term liability, is an obligation resulting from a previous event that is not due within one year. Common examples include:

- Bonds Payable – A promise to pay, related to principal and interest, over a specified period. It is often shown on the financial statements net of the discount on bonds payable. A discount on bonds payable occurs when bonds are issued for less than the amount that it was originally valued.

- Notes Payable – A promise to pay a specific amount of money at a future date. In other words, a note payable is a loan between two entities.

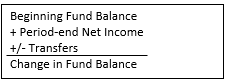

Fund Balance

Fund balance is essentially the difference between assets and liabilities. In general, it is the balance remaining after the assets have been used to satisfy the outstanding liabilities. Very little activity occurs directly within the fund balance accounts and is comprised of the prior existing fund balance and the period’s net income. Different than other parts of the balance sheet, no activity occurs within each fund balance classification and is primarily comprised of income statement activity (net income) and any transfers. The change in fund balance follows the general formula below and is presented as the final line item on the statement of the balance sheet.

For more details and related examples, refer to the UCO-COA-1.02 Fund and Sub-Fund Groups standard. The fund balance is made up of three classifications:

Net Investment in Capital Assets – Consists of the university’s investment in capital assets such as equipment, buildings, land, infrastructure, and improvements, net of accumulated depreciation. Assets held for debt service are offset by the related debt. If there are unspent bond proceeds it should be netted against net investment in capital investment.

Restricted Funds – Consists of amounts subject to externally imposed restrictions governing the use. There are two types of restricted funds:

- Restricted non-expendable funds – Subject to externally imposed stipulations that they be retained in perpetuity. These balances represent the historical value (corpus) of the university’s permanent endowment funds.

- Restricted expendable funds – Expenditures by the university must be spent according to restrictions imposed by external parties.

Unrestricted Funds – Expenditures without restrictions and may be spent on operational needs or a university specified project.

In general, no entries should be posted directly to fund balance accounts. If you believe there should be an adjustment or entry to a fund balance, contact the Accounting and Reporting Services team.

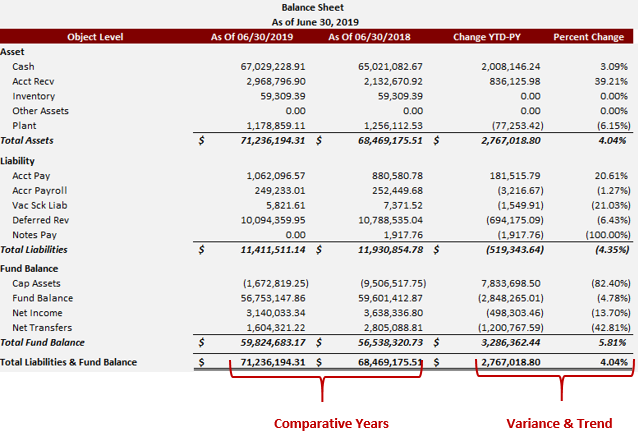

Balance Sheet Presentation

Since the balance sheet reflects financial information at the end of a specified date, users can use this information to assess the overall financial health of the organization. It is often presented as of multiple points in time. For example, the balance sheet may reflect year-end data for two (or more) years. This allows the reader to see variances and trends. This is referred to as a comparative balance sheet. Below is an example of a comparative balance sheet which can be pulled from IU’s internal reporting site, Controller’s Office Reporting Tools. For further information on how to pull a balance sheet, see the Financial Statement Reports instructions.

Requirements and Best Practices

The above paragraphs provide users with a better understanding of the purpose of the balance sheet along with what is included and how the balance sheet is formatted for IU internal reporting. This portion of the standard will discuss how to interpret the balance sheet and procedures all users need to follow when pulling the balance sheet report. By pulling the balance sheet on a regular basis, users are able to ensure an entity’s financial health. It is important that each entity monitors and analyzes their balance sheet on, at least, a quarterly basis. This allows organizations to identify errors, mistakes, and pitfalls which can be remedied quickly and prevent larger issues in the future.

Requirements

The (RC) fiscal officer is responsible for the accuracy, reliability, and completeness of the balance sheet.

Quarterly Activities:

- Run the balance sheet at least quarterly with comparative balances. Please refer to Financial Statement Reports instructions for more information on how to pull the financial statement reports.

- Complete a variance analysis for all operating accounts on a quarterly basis. As part of this process, organizational units need to be able to provide explanations of material variances to UCO upon request only. Please check with your campus and/or RC, as they may require variance analysis submission on a quarterly or annual basis. Please see the UCO-CLS-3.00 Variance Analysis Standard for more information.

Semi-Annual Activities:

- Provide substantiation for any non-system-generated asset and liability balances on your balance sheet. For more information on non-system-generated balances and information on how to substantiate your balances, see the UCO-CLS-2.00 Balance Sheet Substantiation Standard.

Annual Activities:

- Run the balance sheet as of year-end and review for the below information:

- Stale balances are asset or liability balances within the balance sheet which have not changed for a period of time. In order to ensure your balances are accurate, reliable, and complete, organizations are required to review the balance sheet for any stale balances. Stale balances can be identified through the following ways:

- The Office of the Controller has created a Multi-Year Stale Balance report to identify balances that have the not changed for three years. Please refer to the

Multi-Year Stale Balance Report instructions for more information. - Stale balances can also be identified by comparing your balance sheet substantiation for the current year to the prior year. Please see the UCO-CLS-2.00 Balance Sheet Substantiation Standard for more information on the impact of stale balances.

- The Office of the Controller has created a Multi-Year Stale Balance report to identify balances that have the not changed for three years. Please refer to the

- In general, an asset or liability balance is presented as a positive amount within financial statements. To ensure balances are accurate, reliable, and complete, organizations are required to review the balance sheet for any negative balances. The Office of the Controller has created an Account Negative Balance Report to help identify account balances that are negative. Please refer to the Account Negative Balance Report Instructions for more information.

In the event that a balance or transaction is deemed stale, an adjusting/correcting entry needs to be made to adjust the balance. Please see the Closing Standards for more information on how to make the adjustments.

- Stale balances are asset or liability balances within the balance sheet which have not changed for a period of time. In order to ensure your balances are accurate, reliable, and complete, organizations are required to review the balance sheet for any stale balances. Stale balances can be identified through the following ways:

- Determine that there are no negative cash balances at year-end through review of the balance sheet at the account and consolidated object code level. If there are negative balances, are there other accounts with a cash surplus to offset the negative balance?

Best Practices

- Review the balance sheet at year-end and consider the below checklist of questions. The (RC) fiscal officer is responsible for reviewing and analyzing the operational needs of the RC/organization. Analyzing the balance sheet allows the fiscal officer to determine if the current financial position is going to meet the organization’s operational needs. The questions that need to be asked will vary depending on the needs; however, the following questions are some common examples:

- Is there enough cash to support overall cash flow and operations? Are assets greater than liabilities? In general, an entity should try to keep their current assets higher than their current liabilities to ensure enough cash flow for future operational needs.

- Are accounts receivable being collected in a timely manner? In general, an organization should attempt to make timely collections on all outstanding receivables to ensure strong cash flow and maintain actual revenue to budgeted amounts for the fiscal year.

- Are ending receivable balances being reviewed to ensure no negative or stale balances? Balances > 1 year (stale) can artificially inflate the ending receivable balance if the balance is not expected to be received.

- Is inventory too high or too low? When inventory is too high, an entity runs the risk of the inventory becoming obsolete. When inventory is too low, you may not be able to meet the demands of your customer resulting in potential loss of sales.

- Are capital assets fully depreciated? When a capital asset is fully depreciated, it will remain on your balance sheet until the asset is disposed. Fiscal officers should monitor their balance sheet and the useful lives of their assets for planning purposes. For further information regarding the capitalization of assets, see the capital assets and leases standards.

- Is a capital asset replacement needed? If a capital asset is expensive and required for a given entity to function, a plan for replacement is important. For further information regarding the expensing of an asset, see capital assets and leases standards.

- Evaluate the organization’s financial trends for 3-10 years and determine if there are any predictable patterns that may impact future periods. It is difficult to evaluate overall performance by comparing current activity to the prior year only, so performing trend analysis will be beneficial to determine potential issues that could impact the future.

- Analyze the balance sheet and review any discrepancies or errors and consider some big picture questions which may impact your organization’s fiscal health.

UCO-AFO-3.03: Cash Flow Statement

Prerequisites

Prior to reading the Cash Flow Statement standard, it is beneficial to review the below standards to gain foundational information:

- Accounting Fundamentals Standards

- Chart of Accounts and General Ledger Standards

- UCO-AFO-3.02 Balance Sheet Standard

- UCO-AFO-3.01 Income Statement Standard

Preface

This standard discusses the cash flow statement and how it is used internally within Indiana University. Information presented below will walk through a general understanding of the cash flow statement, presentation requirements specifically related to IU reporting, and lastly, will specify requirements and best practices for users of the financial statements. For further information on how to pull the cash flow statement or any of the referenced reports in the requirements and best practices portion of this standard, refer to the Financial Statement Reports instructions.

Introduction

What is a Cash Flow Statement?

The cash flow statement, also known as statement of cash flows, is a financial statement that summarizes the amount of cash and cash equivalents entering and leaving an entity. It is one of the three main financial statements, along with the income statement and balance sheet, and reflects the change in cash within an entity by operating activities, investing activities, and financing activities. Similar to the income statement, the cash flow statement is presented for an entire period, typically a fiscal year.

Indiana University is required to use the accrual method as opposed to the cash basis method of accounting. While this is beneficial in helping to access the revenue stream, expense categories, and overall profitability for a given period, it does make it more difficult to highlight an entity’s cash position. The cash flow statement complements the other financial statements by providing the cash position of an entity so internal and external users can review its overall financial health and position. For more information regarding the two types of accounting, please see the UCO-CLS-1.00 Accruals Standard.

The main purpose of the cash flow statement is to explain the change in cash and cash equivalents. While it has many similarities to the balance sheet, the cash flow statement is focused solely on the movement of cash and excludes almost all non-cash or non-cash equivalent activity. Other common uses of a cash flow statement include:

- To evaluate an entity’s liquidity

- Identify why there is a lack of cash within an entity – typically lack of cash is due to capital purchasing

- Understand the entity’s inflows and outflows of cash

- Show the impact on cash flow from changes in asset, liabilities, and equity

- Allows users to calculate common benchmark ratios such as liquidity, ratio, etc. (financial analysis perspective). See the Financial Ratios document for more details.

- Helps predict future cash flows. Cash flow is the main factor that impacts the interest rate paid on IU debt. Low cash flow results in a higher borrowing rate which has a negative and costly impact for IU.

How is the Cash Flow Statement Organized?

The cash flow statement is comprised of the cash activity in a given period from both the balance sheet and the income statement. Since it includes object codes from both a balance sheet and an income statement, object codes range from 0001 – 9999. It is key to highlight that some object codes within the range may not be available for departments to use because they are either system-generated or are limited to use by either the campus, Treasury, or the Controller’s Office. If you have questions related to balances or system-generated/limited use object codes, please contact your (RC) fiscal officer or campus office.

Presentation Methods

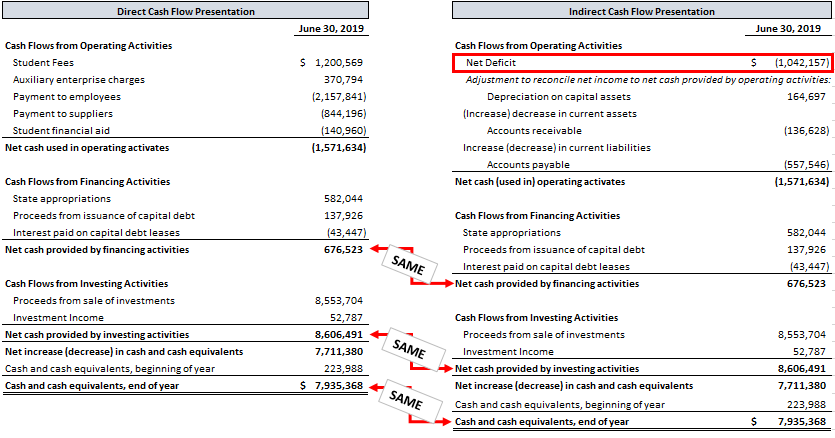

The cash flow statement can be presented in two ways: the direct and indirect methods. Both methods result in an ending cash balance which ties to the balance sheet. The main difference between the two methods is their presentation. The differences between the two methods are as follows:

- Direct Method – This method uses actual cash inflows and outflows from the entity’s operations, such as revenue received from students for tuition, instead of modifying the operating section to include non-cash items such as depreciation.

- Indirect Method – This method uses increases and decreases in balance sheet line items to modify the operating section of the cash flow statement. The beginning line item in operating activity is always the net income for the period pulled directly from the income statement and all other increases and decreases in operating activity are then pulled from the balance sheet. This method is based on accrual accounting and includes cash inflows and outflows that are recorded in the general ledger, but the cash may not have been received or spent.

For internal presentation of the cash flow statement in the Controller’s Office Reporting Tools, the indirect method is used, and users do not have the option to change the cash flow presentation method. For internal purposes, users will not be asked to use the direct method. Refer to Indiana University’s Consolidated Annual Financial Reports for a more detailed example on the direct method presentation.

Below is a comparative example of the direct and indirect cash flow methods of presentation, noting that the ending cash balances remain the same in either method. While the headings are the same, also note how the lines that make up the calculations differ especially under cash flows from operating activities.

Cash Flow Statement General Format

The cash flow statement is a mechanism used to present the cash activity, cash received (inflow), and the cash spent (outflow) in an organized and consolidated manner. In either cash flow presentation method, changes in cash activity are classified in three separate categories: changes in operating, investing, and financing activities.

- Cash Flow from Operating Activities – operating cash flow is mainly related to transactions that come from the income statement. Examples of operating activities on the cash flow statement include cash inflows from students paying their tuition for the semester and cash outflows related to payments to suppliers through BUY.IU.

- Cash Flow from Investing Activities – investing cash flow is related to the purchases and sales of investments and long term/capital assets. Regardless of which presentation method is used for the cash flow statement, the investing activity will be presented in the same manner. For most users at Indiana University, the only activity that should be flowing through investing activities is related to the purchase or sale of a capital asset. A breakout of the activity that is generally included in the investment category on the consolidated financial statements is listed below:

- Includes purchase/sale of investments + investment income

- Includes purchase/sale of capital assets net of depreciation

- Includes purchase/sale of intangibles, business units, patents, etc.

Examples of investing activity presented on the cash flow statement include cash outflows from the purchase of a new building that will be converted into a residence hall and cash inflows from the sale of a truck previously purchased by IU net of depreciation.

- Cash Flow from Financing Activities – cash flows related to the liability and fund balance section of the balance sheet. Activity that is generally include in the financing category at IU is included below:

- Debt and debt related investing activity

- Capital lease payments

- Transfers and subsidies (internal only)

- Activity related to joint ventures

- Bond offerings and repurchasing

For most individual entities at Indiana University, there will be very little activity flowing through the financing section of the cash flow statement other than activity for the income statement transfer object codes – 1699 and 5199. An example of cash inflow would be the issuing of a new bond offering and an example of cash outflow would be the monthly payment for a building lease.

Since the cash flow statement reflects cash activity during a specified period, internal management and external users (e.g., external auditors) can use this information to access the overall financial health of the organization.

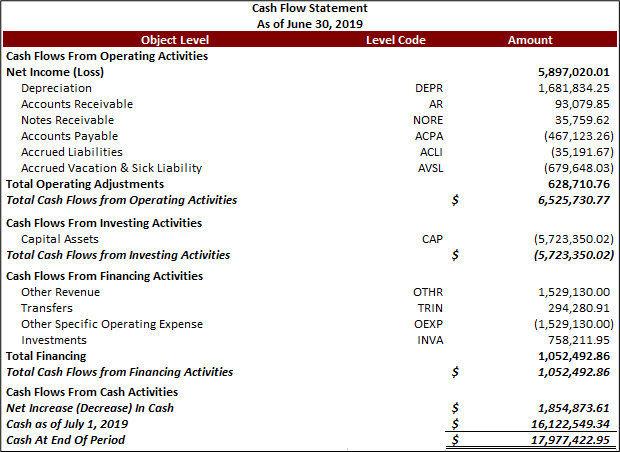

Cash Flow Statement Presentation

Since the cash flow statement shows financial activity over a given fiscal period, internal management and external users can use this information to compare one fiscal period to the next. Below is a cash flow statement extract highlighting the activity in the cash flow statements which can be pulled from IU’s internal reporting site, Controller’s Office Reporting Tools. For further information on how to pull a cash flow statement, see the Financial Statement Reports instructions.

Requirements and Best Practices

The above paragraphs provide users with a better understanding of the purpose of the cash flow statement along with what is included and how the cash flow statement is formatted for IU internal reporting. This portion of the standard will discuss how to interpret the cash flow statement and procedures all users need to follow when pulling the cash flow statement report. By pulling the cash flow statement on a regular basis, users are able to ensure an entity’s financial health. It is important that each entity monitors and analyzes their cash flow statement on, at least, a quarterly basis. This allows organizations to identify errors, mistakes, and pitfalls which can be remedied quickly and prevent larger issues in the future.

Requirements

The (RC) fiscal officer is responsible for the accuracy, reliability, and completeness of the cash flow statement.

Quarterly Activities:

- Run the cash flow statement at least quarterly. Please refer to Financial Statement Reports instructions for more information. Users will be required to run prior year and current year for comparatives.

- Complete a variance analysis for all operating accounts on a quarterly basis. As part of this process, organizational units need to be able to provide explanations of material variances to UCO upon request only. Please check with your campus and/or RC, as they may require variance analysis submission on a quarterly or annual basis. Please see the UCO-CLS-3.00 Variance Analysis Standard for more information.

- Determine if the ending cash balance is negative through quarterly review of the cash flow statement. If it is a negative balance, what line items are causing the negative balance?

- Compare inflows and outflows of cash to examine where cash is being expended or received in your entity. In instances where units have positive cash flow balance due solely to transfers from IU Foundation or subsidies, ensure timing of transfers and appropriate reserves in the event transfers do not occur timely.

- Campuses and some units will have specific cash reserve requirements. Check with your campus budget office for further information. Review IU policies and requirements for reserve requirements to ensure your entity is in compliance.

Best Practices

- Review the cash flow statement at year-end and consider the below checklist of questions. The (RC) fiscal officer is responsible for reviewing and analyzing the operational needs of the RC/organization. Analyzing the cash flow statement allows the fiscal officer to determine if the current financial position is going to meet the organization’s operational needs. The University Controller’s Office recommends using standard cash ratios to assess cash balances and liquidity. The questions that need to be asked will vary depending on the needs, however, the following questions are some common examples:

- Is there enough cash to support overall cash flow and operations? An entity should always keep their ending cash balances and activity positive to ensure enough cash flow for future operational needs.

- Is ending operating cash activity for the period negative? If the ending operating activity is negative, it means that the entity expended more cash than they received during the year. This may indicate that expenses need to be cut or a revenue stream underperformed that will need to be further analyzed.

- Does debt activity outweigh general operating activity? In periods with high financing activity, this could indicate a future cash flow issue.

- Evaluate the organization’s financial trends for 3-10 years and determine if there are any predictable patterns that may impact future periods. It is difficult to evaluate overall performance by comparing current activity to the prior year only, so performing trend analysis will be beneficial to determine potential issues that could impact the future.

- Analyze the cash flow statement and review any discrepancies or errors and consider some big picture questions which may impact your organization’s fiscal health.

The review of operating reports monthly to ensure that the revenue and expenditures posted to the account are those that were approved by the Fiscal Officer, or their delegate, and that they are allowable and appropriate.

Fund balance is essentially the difference between assets and liabilities. In general, it is the balance remaining after the assets have been used to satisfy the outstanding liabilities.

A main concept of government accounting, an encumbrance is is a restriction placed on the use of funds to ensure there are enough funds for future expenses/obligations such as salary, loan payments, etc.

A fiscal period at Indiana University is broken out into 12 separate periods based on months in the calendar year. Period one is equivalent to July during the fiscal year.

The Adjusted Base Budget is defined as the initial July 1 budget load adjusted throughout the year through the use of base budget adjustments. The adjusted base budget is the basis for budget construction for the upcoming fiscal year.

The Current Budget is loaded along with the base budget load on July 1 and adjustments through the use of current budget adjustments are reflected for the current year only.

Monthly budgets allow departments to spread their annual budget into 12 different buckets. This is important when entities have revenue and expense lines that are not earned or incurred evenly over the 12 months of the fiscal year.

An income statement, also known as the statement of revenues, expenses, and changes in net position, is a financial statement that summarizes the revenue streams, expense categories, and overall profitability of an entity.

A cash flow statement, also known as a statement of cash flows, is a financial statement that summarizes the amount of cash and cash equivalent entering and leaving an entity.

A debit is an accounting entry that either increases an asset or expense account, or decreases a liability or equity account.

A credit is an accounting entry that either increases a liability or equity account, or decreases an asset or expense account.

Cash is money in coins or notes, as distinct from checks, money orders, or credit.

Cash equivalents are short-term assets that are easily and readily converted into a know amount of cash.

A balance sheet, also known as the statement of financial position, is a financial statement that reflects the overall financial position of an organization at a specific period in time.

A fiscal year at Indiana University spans from July 1st through June 30th of the subsequent calendar year. The last day of the fiscal year is June 30th.

Accrual accounting is a method that records revenue when it is earned and records expenses when they are incurred, not when the cash is received. Different than cash accounting, this method provides a more realistic understanding of income and expenses and helps with long term projections.

Accounting method which records revenues and expenses only when monies are exchanged.

Liquidity refers to the ease with which an asset, or security, can be converted into ready cash without affecting its market price. Cash is the most liquid of assets while tangible items are less liquid.