Structural Competency

Abstract

Keywords:

structural competency; student affairs; higher education; racial justice; critical race theory

1. Introduction

These are not just ugly narratives of our past; rather, U.S. colleges and universities remain committed to the project of racialized oppression and violence [8,9]. The legacy of U.S. chattel slavery persists through ongoing projects as well as institutional infrastructures. Colleges and universities use investments in private prisons to bolster their economic standing [10], implicating them in the care and maintenance of the “new Jim Crow” [11]. Scholars have demonstrated that all postsecondary U.S. schooling institutions, continue in norms, culture, and function, to be rooted in a plantation politic [12].

Plantation policies and practices continue to disadvantage students from racially minoritized backgrounds. BIPOC students struggle to gain access to postsecondary institutions and even more so, elite colleges and universities [13]. When they do, they experience the harmful consequences of existing in racist spaces [14,15]. These well documented racial disparities in higher education cannot be explained by incidents of individual prejudice. They stem from structural forces that embed racial bias through institutional decision-making, norms, culture, and race-evasive public and institutional policies [12,13,14,15,16].

Less than fifty years after higher education institutions stopped officially excluding BIPOC students, the retrenchment of short-lived civil rights policies and commitments has resulted in declines in Black and Latina/o/x student enrollment at many highly selective colleges and universities around the U.S. [17]. A 2020 report by the Education Trust entitled “Segregation Forever”, found that the percentage of Black students has decreased at nearly 60% at the 101 most selective public colleges and universities. In the report, over 75% of the colleges studied earned an F grade for their representation of Black students [17]. As it relates to Latina/o/x students, nearly half of these colleges earned an F grade for their representation of Latina/o/x students [17]. These previously mentioned statistics are markedly before the potential end of Affirmative action by law (anticipating upcoming Supreme Court decisions in SFFA v Harvard and SFFA v UNC). Lastly, in a report authored by Carnevale and colleagues [18] whites have almost two-thirds (64%) of the seats in selective public colleges even though they make up little more than half (54%) of the college-age population.

The lack of representation of BIPOC students, particularly for those who are Black, Indigenous, and Latina/o/x is a problem that extends beyond elite and highly selective colleges and universities. For example, the California State University (CSU) system, which is the largest four-year university system in the U.S., continues to struggle with Black student enrollment. Shaped by over two decades of affirmative action state-ban restrictions, Black student enrollment declined by 7000 students in the CSU system, from 2008 to 2020 [19]. The graduation rates for Black students are just as meager; the CSU is only graduating 48% of its Black students compared to its white students at 72%; in the past 15 years, the graduation gap between Black and white students has grown [20]. In the California Community College system, the largest postsecondary system in the U.S.; 63% of Black community college students do not earn a degree, certificate, or transfer within six years [21]. These inequities persist in part because of legacies of racism embedded in policy, for example a report by Levine and Ritter [22] states;

Racial disparities creep into the [financial aid] system because the federal formula for estimating how much a family can afford to pay for college ignores a family’s home equity in their primary residence and the value of their retirement savings. Families that own more of these “uncounted” assets have greater financial resources than families that do not. Yet, at similar income levels and other asset holdings, families that own their home or have retirement savings are given the same level of financial support for college as those without. …white families are far more likely to own these uncounted assets and at higher levels, which generates racial disparities in college affordability.(para. 3)

They go on to mention that, white students receive an implicit subsidy that is $2200 per year, on average, more than for Black students [22]. These realities shaped by policies and upstream decisions make it more difficult for BIPOC students to access college, graduate, and even leave college with little to no debt. Simply put, higher education reinforces the intergenerational reproduction of white racial privilege [23]; thus, why a structural competent approach is vital.

Our purpose in this paper is to adapt the well-established medical framework of structural competency for application in student affairs training and practice. We do so through a CRT lens, to allow for a focus on addressing how racism shapes structural violence and the conditions that give rise to postsecondary racial disparities. Guiding by CRT, we name that building capacities toward understanding structural racism can enable more effective student affairs practices in support of BIPOC students thriving. Our aim is for this framework to shape the education and critical consciousness of student affairs practitioners, through its use in student affairs and higher education graduate programs, staff recruitment, staff onboarding, and staff professional development.

We follow Jayakumar’s [24] lead in borrowing from developments in the medical field, to argue for a shift in educational research and discourse from “cultural competence” to “structural competence”. This strategy is in harmony with other current shifts in higher education research, such as Ledesma’s [25] argument about the need for a shift away from “positive racial climate” to “healthy racial climate” [24]. More than superficial changes in nomenclature, these shifts attempt to correct how focusing on “positive climate” and “cultural competence” has been taken up in ways that individualize racist harms or encourage surface level changes. Our proposed alternatives move toward systemic and contextual understandings of higher education institutions and U.S. racial realities. We center the upstream decisions that perpetuate structural violence and create racial inequities in higher education, even when the ways they harm students seem local and personal (and therefore, to some observers, easily dismissed as unimportant) [24].

Nearly twenty years ago, Ladson Billings argued for her groundbreaking “cultural competency” framework, important for calling out how white dominant pedagogical approaches and curriculum harm BIPOC students by erasing and invisibilizing their community histories, epistemologies, and oppression. Yet too often, student affairs practitioners and administrators who understand the urgency of creating inclusive environments for students of color have misguidedly adopted a cultural competency approach that encourages tolerance, multicultural diversity, and a positive racial climate by celebrating (and often tokenizing) racial difference and understanding. Helpful as cultural competency approaches have been, we argue that in higher education specifically, they seldom do enough to engage with the policies and practices that actually produce and reproduce systemic racism on campus and harm BIPOC people who study and work there. Additionally, as we will argue below, they can assist in covering over and perpetuating structural causes when users focus on individual difference.

The move from cultural competency to structural competency comes to us from other helping fields where cultural competency has been misused in decontextualized ways that ignore how “culture” is shaped by systems of oppression [24,25,26]. It has its roots in scholarship from medicine [26], law, [27], mental health [28], history [29], and sociology [16]. Structural competency addresses “social needs”—and their links to race and racism [30]; Doctors and clinicians use the structural competency framework to reveal the pathologies of institutions and policies that breed oppression and suffering in individuals, communities, and groups, and create models that promote mental and physical wellness among clients [26].

The model is ripe for extension in higher education, where cultivating structural competency can crucially reshape faculty and staff understanding of what structural factors are at work in given situations, what equity and justice could look like on college campuses at the structural level, and how to support generative spaces where BIPOC students thrive [24]. Because structural competency increases recognition of the upstream decisions that make higher education institutions inaccessible, hostile, and inequitable for BIPOC students, the model is useful not only for student affairs professionals, but for leaders and policy makers dedicated to moving beyond superficial fixes toward authentic racial justice in higher education [24]. In this paper, we focus on making the shift from cultural competency to structural competency in student affairs preparation and practice.

2. The Limitations of Cultural Competency

Twenty years ago, a focus on cultural competency in the medical and public health field became an important framing strategy. It brought to focus the ways in which U.S. medicine failed to acknowledge the importance of diversity and inclusion [26]. Ladson-Billings [31] conceptually broadened the need for cultural competency in K-12 classrooms, and eventually the concept made its way to the field of higher education. Cultural competency grew into a prominent educational theory that supports educators in interacting with BIPOC students in authentic and culturally responsive ways. Cultural competency challenged prevailing deficit framings of BIPOC students [32], as well as curricular and pedagogical practices that placed requirements for academic success in tension with students’ cultural identities, community values, and socio-historical truths [31,33,34].

Speaking to the field of teacher education, Ladson-Billings [31,33], described cultural competency not only as a tool for encouraging (as opposed to undermining) academic success, but also as a lens that could empower educational agents to recognize, comprehend, and critique contemporary social inequities, shaping the educational experiences of BIPOC students. Her definition includes the capacity for educators to be able to identify political underpinnings in students’ communities and social worlds, inclusive of racialized realities and oppression. In the field of higher education and student affairs, Pope et al. [35] popularized their version of cultural competence, describing multicultural competence as “a distinctive category of awareness, knowledge, and skills essential for efficacious student affairs work” (p. 9). This framing of cultural competence as awareness of multiplicity has been influential in scholarship, as well, and particularly useful in studies examining the educational benefits of campus diversity, a concept with a crucial role in legal advocacy for race-conscious admissions [36,37,38] but does not sufficiently focus on structural oppression as it shapes BIPOC student and community experiences. Cultural competence has been important for pushing student affairs practitioners to better serve BIPOC students, and in any field, it can be a vital and important tool [26,31].

Like Ladson-Billings, Pope and colleagues [35] argued for the importance of challenging “systems around oppression issues in a manner that optimizes multicultural interventions” (p. 19). However, this objective of cultural competency has often been lost, when practitioners take up the more palatable parts of the term that fit within their student affairs practice, “competency” is diluted to “learning about ‘other’ cultures”, and is then considered part of the educational benefits of superficial multicultural diversity, benefits which, it has been shown, continue to accrue to white applicants and students most of all [39,40]. As a model and framework, cultural competency has often not accounted for the structures that marginalize BIPOC students even when they have dedicated, aware advocates on campus.

Borrowing from the medical and health sciences, we argue that the concept of structural competency can do a better job emphasizing the need to address oppressive systems, policies, practices, and norms. Building on the legacy of Ladson-Billings and Pope, who called for a focus on racialized structures and transformative interventions, adding structural to cultural competence can push the conversation toward intervening on the ways institutional structures (policies, practices, norms) produce racialized experiences and outcomes by design. And importantly, how we can create and imagine more humanizing and just structures and educational spaces.

3. Competencies in Students Affairs Education and Training

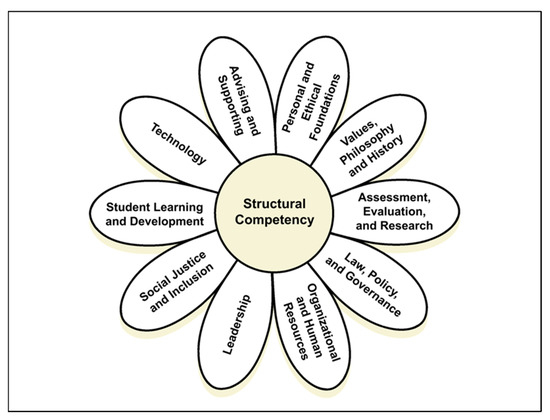

The Professional Competency Areas for Student Affairs Educators, authored by ACPA and NASPA [41], outlines professional standards for people who work in student affairs. The ACPA and NASPA competencies are regarded as the standard for the field of student affairs, shaping required curriculum for accredited student affairs graduate programs, and guiding student affairs practice and professional development. They cover ten content areas, such as personal and ethical foundations; philosophy and history; assessment, evaluation, and research; and law, policy, and governance. They also incorporate a competency that discusses social justice and inclusion [41]. While expansive, the ACPA and NASPA standards fail to accurately account for how race and racism are at the center of most, if not all, forms of oppression. As Poon’s [9] asserts in her critique of ACPA and NASPA [41] competencies: “notions of social justice, equity, and inclusion remain segregated and marginalized in higher education” (p. 15).

In the student affairs professional competencies social justice is a stand-alone competency, rather than a learning competency that is included within all competency areas, since all of the competencies mentioned—from doing assessment to choosing whether to comply with local or national policies—cannot be divorced from racialized structures and how minoritized student experiences and outcomes are in relationship with those structures. BIPOC students are not only marginalized in higher education at diversity trainings or social justice events, but also through structural forces: the policies, institutions, infrastructure, and the hegemonic beliefs embedded in our economic, social, and political systems, with which our students interact every day [26,42]. For example, research on structural racism shows that campus policies create unequal outcomes for BIPOC students in all areas of their lives [23], not merely in one student affairs competency or another. We argue that structural competency needs to be at the core of student affair standards, as depicted in Figure 1.

4. Towards Structural Competency in Student Affairs

Metzl & Hansen [26] conceptualized five structural competencies that make up their structural competency framework: (a) Recognizing the structures that shape clinical interactions; (b) developing an extra-clinical language of structure; (c) rearticulating “cultural” presentations in structural terms; (d) observing and imagining structural intervention; and (e) developing structural humility. In this paper, we adapt Metzl & Hansen’s framework for student affairs and add a sixth competency: structural intersectionality [43]. The implications of the aforementioned competencies include the downstream consequences of upstream decisions. This language around “downstream consequences of upstream decisions” is borrowed from the helpful imagery utilized in discussion of structural competency in medicine for explaining that organizational decision-making by those with power (upstream decisions) directly shapes racialized outcomes/disparities (downstream consequences) [26]. Each competency is helpful in contextualizing matters that impact racial justice on college campuses, including but not limited to: the quality of K-12 schools [44]; admissions standards at colleges and universities [45,46]; access to food and housing [47]; financial aid packages [48]; access to supplemental education and tutoring [49,50]; faculty-student engagement; and overall sense of belonging [15].

For institutions that theoretically support “diversity”, it is a substantial shift toward putting structures in place that subvert hegemony and create racial justice practices that empower BIPOC students and institutional agents. Cultivating structural competency is not possible without centering race and racism. Before we unpack the adaptation of these original five competencies and the integration of the sixth competency from the health fields to higher education, we argue that student affairs practitioners (as well as administrators and policy advocates) must understand structural violence and structural vulnerability (both important aspects of structural competency), and how Critical Race Theory (CRT) supports centering racial justice as fundamental to advancing structural competency.

5. Structural Violence and Structural Vulnerability

In general, the word violence often conveys a physical image [51]; however, Farmer et al., [51], quotes Galtung’s helpful description of it as the “avoidable impairment of fundamental human needs or…the impairment of human life, which lowers the actual degree to which someone is able to meet their needs” (p. 1686). Structural violence is carried out through social structures that stop individuals and communities from being successful, and without recognizing its role, we cannot understand the pathologies and policies of institutions that create violent living conditions for individuals and communities. Structural violence is often embedded in longstanding social structures, normalized by the institution and therefore often unseen, that results in inequitable access to political power, health care, higher education, employment [51], and we would add, humanization and personhood.

While a focus on cultural competency can lend itself to practitioners creating individualized strategies (as opposed to structural ones), structural competency enables us to move beyond this tendency, and to lift up how BIPOC student vulnerabilities are often connected to structural violence [24]. In higher education, institutional power dynamics can intensify individual students’ academic circumstances and the problems they face. Structural vulnerability means that a student’s potential exposure to harm does not exist in a vacuum but is reflective of broader dynamics shaped by structural violence [24]. We must understand the implications of these dynamics, in ways that shape how we respond to students reaching out for support services, expressing experiences of marginalization, or seeking redress over a conflict or harm.

Attention to structural vulnerability is vital for student affairs practitioners to understand: Who is structurally vulnerable? Additionally, how can this understanding shape our practice and the interventions we imagine? Being able to answer these questions requires structural competence, which can support student affairs practitioners in their role as primary institutional agents tasked with identifying and intervening when a student can benefit from additional services offered by the campus and external community. Assessing structural vulnerability enables us to measure a student’s financial security, access to healthy food; whether a student has access to a supportive network (mentors and peers); if they are being surveilled by the police—and even, by student affairs practitioners; and access to safe housing. It is an opportunity for student affairs practitioners to redress campus policies, to ensure future students do not fall to the same fate; being able to identify and articulate that racially minoritized students—and Black students in particular—are more vulnerable to ongoing structural violence and harms; and perhaps most importantly, to support BIPOC students in securing alternative conditions of joy and pleasure, free from everyday structural violence.

This can also help student affairs practitioners in not catering to white student discomfort and claims of harm in ways that end up creating undue harm toward BIPOC students. Thus, structurally competent student affairs practitioners are invested in tending to all students’ experiences, needs, and complaints with support, compassion, and the appropriate resources. However, they are equipped to do so with the capacity to determine an appropriate response that accounts for how a particular students’ experience, need, or complaint, is shaped by structural violence and whether (or not) a structural vulnerability exists. Structural competency in student affairs means having the capacity to reflect on how the policies, practices, trainings, and norms of the profession, contribute to structural violence and often ignore BIPOC students’ structural vulnerabilities, as well as cater to white students not experiencing a structural vulnerability.

In order to address the challenges related to violence and vulnerabilities, it is necessary that we precure resources beyond that of the institution. We must consider how to leverage resources in the community at-large that students can access. Over the longer term, a new structural competency curriculum can expand the vocation and imagination of student affairs practitioners toward creating better access for BIPOC students.

6. Conceptual Framework: Critical Race Theory

CRT is a framework developed by legal scholars—Derrick Bell [52], Kimberlé Crenshaw [53], Cheryl Harris [54], Richard Delgado and Jean Stefancic [55] amongst many others—for understanding and challenging how the dominant legal paradigm, by design, legally protects and advances white normativity and supremacism through the subordination/subjugation and dehumanization of Black, Indigenous, and other people of color. It has since been utilized in the field of education to hone in on the role of racism in schooling practices and structures [56,57,58,59,60]. Across fields, CRT is a movement focused not only on naming how racism is situated as an always present and foundational construct that organizes U.S. institutions and everyday life, but also on challenging and transforming racist structures [53,54,55,57,58,61]. Dumas and ross [62] add to our understanding of CRT in education’s central tenet asserting the pervasiveness of racism. Their articulation of BlackCrit “helps to explain precisely how Black bodies become marginalized, disregarded, and disdained, even in their highly visible place within celebratory discourses on race and diversity [62] p. 417.” Moreover, whiteness is dependent on antiblackness, and this power relationship is embedded in structures (policies, practices, norms) that reinforce black subjugation toward upholding racism [62,63,64].

While structural competency frames structural violence and vulnerability more broadly, using CRT as a conceptual framework supports an adaptation of the medical model for student affairs that starts with an analysis of racial oppression and understands dominant institutions such as the legal system and higher education as mechanisms for the production and maintenance of white normativity and supremacism, dependent on black dehumanization. Where whiteness is the dominant ideology, CRT shows us, it will hide the racist structures that perpetuate and maintain racial inequities, enabling them to be seen as normal, while they operate in the shadows [55]. We utilize CRT to adapt Metzl and Hanson’s framework (see Table 1) to respond to the ways in which racism and other forms of oppression are embedded in systems of higher education—CRT helps us to identify upstream racism, so that we can move towards a framework of redress and justice.

CRT is especially useful for thinking about interventions in the field of student affairs, a field which tends to engage in a politic of inclusion that often results in the exclusion of race, as opposed to building on understandings of race and racism toward intersectional inclusion goals. To put it differently, a structural competency approach might question why student affairs interventions aimed at including minoritized communities such as women, LGBTQIA+ students, students with disabilities, and students who experienced foster care tend to ignore race, when BIPOC students are a part of each of these communities. CRT calls for an analysis of intersecting forms of oppression, without de-centering race/racism. Below, utilizing CRT we unpack the adaptation of each competency.

7. Adapting Competency One

Metzl and Hansen’s [26] first competency focuses on recognizing the structures that shape clinical interactions. For student affairs, this means identifying and understanding how structures, including racialized power dynamics, shape the relationship between institutional agents (the practitioner) and BIPOC students, as well as reflecting on the ways in which institutional policies and norms shape the contexts under which student-practitioner interactions occur. This first competency anchors structural competency. In higher education, economic, physical, and socio-political constructs impact campus interactions and decision-making from admissions to financial aid to housing. Structural competency means (re)considering how institutional policies and practices that student affairs practitioners replicate (or have the potential to disrupt) on a daily basis, impact BIPOC student experiences and outcomes. For example, it means asking, what structural forces dictate admission standards for the university? Or what structural forces decide the cost of on-campus housing, tuition, and fees?

Our adaption centers on recognizing how racialized structures shape student-practitioner relations and interactions. A recognition of structure will ask higher education practitioners to approach student interaction differently, we use two examples to illustrate. Our first example, centers the hidden structural harms of financial aid policy. For a BIPOC student who is struggling financially, a structural competency approach will call for student affairs practitioners to look at how a student might not be inclined toward trusting structural supports, such as financial aid, that can be complicated to navigate and secure. In addition, given the economic climate, the student may be student loan adverse. Student affairs practitioners will not only analyze this case from the individual needs of the student, but they will also seek to understand the structural forces, meaning that regardless of the amount of financial aid awarded, the student still might not be able to afford the cost of attendance.

Recognizing the structures that shape students’ experiences means knowing how state and federal taxes dictate inflation of tuition dollars, and how this disproportionately impacts communities of color who do not benefit from historical subsidized housing and education programs that concentrated accumulating wealth among whites and white communities [65]. Through a lens of structural vulnerability, when BIPOC students experience marginality, we understand these experiences as tied to large institutional structural violence that can make it difficult for them to meet their basic needs. Our second example, highlights when Black students protest and name experiences of marginality and racism on campus, that it is different from white students who express feelings of marginality based on claims of perceived “reverse racism”. The former is tied to structural violence and vulnerability, and the latter is not [24]. The work of CRT scholar Cheryl Harris [54] on whiteness as property, when added to a structural competency approach, clarifies why the former is often followed by violence from campus police, while the latter is not: structural violence aimed at BIPOC students is ensured by a system that protests whiteness as a property right. Such protections of white personhood are not extended by law to BIPOC individuals, and they often ensue at the cost of BIPOC dehumanization and violence. For student affairs practitioners, knowing how to identify structural racial violence is crucial to articulating a differential practice when it comes to BIPOC versus white claims of harm that serve to uphold whiteness as property, and to know what to do.

8. Adapting Competency Two

Metzl and Hansen [26] describe the second competency as developing an extra-clinical language of structure. This competency shifts emphasis beyond the institution or its departments by imparting disciplinary and interdisciplinary understanding of structures. In adapting this competency towards racial justice using CRT, it is important to name racist structures on postsecondary campuses and greater communities, and to develop a language for naming structural racism in the training and onboarding of student affairs professionals. Converging this competency with CRT enables us to develop a language that names whiteness and intervene when it attempts to masquerade as neutral and innocent [9,54]. To adapt competency two, we draw on the groundbreaking work of Critical Race Legal Scholar, Lani Guinier [66], on racial literacy, which she defines as “the capacity to decipher the durable racial grammar that structures racialized hierarchies and frames the narrative of our republic” (p. 100). It is essential that student affairs practitioners and those in the profession develop “racial literacies” [46,66,67,68] towards being able to read the ways in which their everyday practices in higher education are shaped by—and either disrupting or reaffirming– racialized policies, structures, and norms.

In “Ending White Innocence” in Students Affairs and Higher Education, Poon [9] asked, “how many course syllabi for Higher Education History classes in student affairs and higher education programs center questions and analyses of racism and settler colonialism as fundamental to the development of higher education in the U.S.?” (p. 19). This rhetorical question is an example of Competency Two in practice. The importance of interdisciplinary literature that interrogates structural racism is vital to student affairs and higher education graduate programs. Cultivating racial literacy in student affairs practitioners means they will be better poised to develop an extra-clinical (or in our case, extra-student affairs) language of structure, centered on racial justice.

9. Adapting Competency Three

Metzl and Hansen [26] describe the third competency as rearticulating “cultural” presentations in structural terms. This competency supports student affairs practitioners in understanding, the way social structures interact with students’ academic lives, for example, leading to struggles and sometimes academic probation. Being able to reformulate cultural presentations—and we would add—specifically those often aligned with deficit assumptions, is crucial. This may require iterative conversations and explorations of root structural challenges. Our adaptation of this competency is slightly different (and specific)—rearticulating “cultural” presentations aligned with deficit assumptions, in structural terms.

For example, a student of color has their head down in class and seems to be disengaged, when in reality, they have not had a meal of sustenance in several days and are having a hard time focusing. A structurally competent approach would help us understand what policies and infrastructures are contributing to the student’s food insecurity. In adapting this competency towards racial justice using CRT student affairs practitioners need to interrogate how factors like race and class converge with postsecondary and public policy that led to the student being unable to afford food. Thus, we must look beyond the behavior to interrogate structural roots. This means being curious, learning from our students about their experiential and racialized realities, but not assuming that BIPOC students have economic hardships.

The adaptation of Competency Three is important as it moves student affairs practitioners away from pathologizing or stereotyping BIPOC students as students who simply do not want to learn. Rather, it invites us to understand the structural forces behind our current basic needs crisis in higher education [69]. We are able to move away from the downstream consequences and focus on the upstream decisions such as the legacy of racist policies like redlining [70], and neo-liberal projects that contribute to gentrification [71], both consequently pushing BIPOC people out of their neighborhoods and networks of care.

10. Adapting Competency Four

The fourth competency is described as observing and re-imagining structural interventions [26]. This competency is about understanding how structures harm people and applying that understanding to strategically and creatively remove racialized power structures, rather than blindly following normalized practices that compound harm. Oftentimes student affairs practitioners work in silos, disconnected from the campus and external campus community, using “micro” interventions, themselves compartmentalized in nature, that unfortunately are not conducive to addressing structural racism [42]. We adapt this competency using CRT which is described as, observing and re-imagining structural interventions that resist white normativity. We assert that we must (re)imagine structural interventions that resist white norms, are not top down, and are connected to BIPOC student’s lived experiences and community-based knowledge.

Higher education policies are reflected in the financial, legislative, and organizational decisions made at particular moments in time. Given higher education’s racist legacy, these policies favor white male affluent students. BIPOC students need intervention strategies that are holistic and support their unique needs. (Re)imagining structural intervention requires student affairs practitioners to work in concert with faculty, academic advisors, directors of student service programs, deans, and university presidents. This work cannot be about merely building consensus among those in the room. Rather, it means challenging white normative perspectives and practices when they arise amongst these institutional agents, and always centering the needs of the most racially minoritized students and excluded communities not yet in the room.

This competency supports Chambers & Ratliff’s call to “pivot from oversight to advocacy, while ultimately striving toward larger structural changes” [42] p. 66. As the Black American proverb reminds us, “the system is not broken, it was built this way”. When student affairs practitioners are able to see how the system has been built by and for the perpetuation of racism, they can be better advocates for BIPOC students, and employ structural interventions that intercept some of the challenges institutional policies and practices manufacture, by design, that harm BIPOC students. While change does not happen overnight, Competency Four is important to use for harm reduction, as we work to redress the upstream inequities.

11. Adapting Competency Five

Metzl and Hansen [26] describe their competency as developing structural humility, which is the trained ability to recognize the limitations of structural competency [26]. We adapt to Metzl and Hansen’s version to connect it with addressing racism in higher education, with developing structural humility toward an ongoing critical race praxis. Here, student affairs practitioners must demonstrate a critical awareness of realistic goals and endpoints. Awareness of the complexity of racial equity and justice is paramount. Race is a dynamic construct that is always changing. As Delgado and Stefancic [55] explain, “races are categories that society invents, manipulates, or retires when convenient” (p. 8). The players change, but the harsh reality that CRT teaches us is that racism is not going away; white supremacy will re-create and re-imagine race when it is challenged, to preserve a racial hierarchy that protects whiteness and the privileges it comes with [55]. Thus, we must always have a learning stance toward understanding racialized structures and their impact on students, and humility around our own structural competency.

Structural humility in higher education is important in responding to the structural forces that are invented and reinvented to marginalize BIPOC students. It is consistent with a critical race praxis approach of continuing to understand and evaluate the shifting dynamics of racism, and changing our interventions accordingly [72]. Student affairs practitioners must lean into structural humility, and not assume that their institution has “arrived” or has it “right”. Practitioners must reflect on their own internalized racism, as well as, the ways in which institutional bodies internalize racism. For example, Hispanic Serving Institutions, or programs designed to support racially minoritized students, often reproduce the same racist practices (e.g., respectability politics) that have been levied against them. In responding to how racism shifts over time, student affairs practitioners need to develop these skills as the starting points of conversations, advocacy, and resistance rather than endpoints—it is about the process, not the product.

For example, imagine a student affairs professional, who in their undergraduate student years, organized protests, sit-ins, and even put forth demands for addressing institutional racism. They may now have to shift and be more expansive in the strategies they rely on to intervene on racial injustices and to create more humanizing educational conditions for BIPOC college students to experience joy and thrive. A structural competency approach calls for a critical race praxis that is intentional about the different sources of power that are available to students versus institutional agents, and in their current role work strategically and collectively toward institutionalizing long term structural changes based on BIPOC activist students demands.

12. Integrating a Sixth Competency

We add to Metzl and Hansen’s framework, by integrating a sixth competency: taking a structural intersectionality approach. It centers on how individuals experience compounded marginalization given their interactions with the multiple structures of gender, class, hetero- and cis-normativity, and more [43,53]. In cultural competency-oriented student affairs work, as we have argued, there can be a tendency toward de-centering race as the critique of systemic racism is expanded out to account for other areas of oppression. Similarly, intersectionality—a key approach of CRT—can be taken up in ways that stray away from its structural roots (as defined by the Black feminist scholars who introduced the term) toward a conversation about multiple identities. Structural intersectionality, especially when viewed through a critical race theory lens, calls for a focus on oppressive structures, for centering race/racism while adding other forms of oppression-informed identity formations.

The integration of the sixth competency focuses on the ways in which institutions are marginalizing BIPOC students; racism is still the prevailing force that is marginalizing people across structures. For example, structural racism within the criminal justice system and federal financial aid polices [73] impacts BIPOC students being able to access postsecondary enrollment and completion. Taking a structural intersectional approach helps to understand the ways in which institutions like higher education, health care, and housing are not set up for certain students to be successful. Our understanding of structural racism cannot be just located in higher education, it is important for student affairs practitioners to understand how various structures work together to oppress BIPOC students.

13. Case Study

What difference does a shift to structural competency make, on the ground? To illustrate the potential, we draw on a story from the first author’s experiences working in student affairs for over a decade. (To protect the anonymity of the student, we’ve used a pseudonym and alter some aspects of the story.) Mary is a freshman and the first in her low-income, Black family to go to college. At the dining hall with a friend, Mary realizes she only has a couple of meals left on her dining plan for the week. In an effort to stretch out her meals and save money, after she and her friend finish eating, Mary grabs some extra food to eat later in her dorm, something she’s seen other (white) students do frequently. However, a staff member stops her, accuses her of “stealing”, and proceeds to call the cops. From a structurally competent approach, what immediate and long-term steps should be taken?

Immediately, it is important to understand how this student is being racially criminalized for something that her white peers do every day. Secondly, a structurally competent approach would not criminalize Mary, but rather ask why she cannot afford food at their campus. Instead of reporting Mary and seeking her arrest because she’s hungry, structurally competent staff would talk, ask questions, and support Mary’s basic needs. The staff member needs to stop the practice of surveilling students, student affairs practitioners need to move from mandatory reporting to mandatory supporting.

Instead of advocating for the student to be arrested, the staff member should use their positionality as professionals on campus to advocate for Mary and other students suffering food shortages. Additionally, given the ways that the ever-increasing costs of attending college shut many BIPOC students out of access to a postsecondary degree, or to having basic needs met when they arrive, a structurally competent approach by the university itself would be to solve the upstream issues, via reducing the cost of food and other basic needs on campus and providing more scholarship and grant aid for BIPOC students to pay for college.

We recognize that the staff member that confronted Mary does not have the immediate power or positionality to make instant system-wide change, however, as we mention earlier in competency four, student affairs practitioners need to pivot from oversight to advocacy. Jayakumar and Adamian [72] name this as relational advocacy toward mutual engagement; this encompasses a multilayered approach towards “working within oppressive policy constraints with a critical consciousness, while simultaneously changing policy” (p. 37). Student affairs practitioners can take intermediate steps and advocate for change in department and campus-wide meetings. Student affairs professionals can also be strategic when serving on campus, regional, and national committees to bring attention to and advocate for students. Lastly, student affairs practitioners can advocate for equity minded policy change on the local, state, and national levels.

14. Conclusions

The structures that marginalize students are sometimes invisible to administrators—but that does not mean they are not identifiable. We underscore the urgency to advocate for students who experience blatant and obscure racism and other forms of structural violence that robs them of an education that supports them in thriving. Addressing pervasive inequalities and exclusionary practices in postsecondary spaces requires that student affairs practitioners understand and tend to the structural forces that create dehumanizing conditions and disparate outcomes. Prior competence frameworks in education emphasized the ability to connect with minoritized students in ways that honored their identities and communities; however, they lacked a focus on exposing the racialized structural forces that hinder students’ ability to thrive. Working towards structural equity and racial justice means recognizing, naming, and appropriately challenging the structural forces that dehumanize and limit BIPOC students from advancing in higher education. This is important as many diversity efforts and attempts to expand access/inclusion for broader groups tend to do so at the exclusion of race, even when there are BIPOC people within the new identity category.

Our use of structural competency and integration of Critical Race Theory to center racial justice increases student affairs professionals’ recognition of the upstream impacts that make higher education institutions inaccessible, hostile, and inequitable for BIPOC students. Structural competency training can equip current and future student affairs professionals with a uniquely innovative understanding of the social determinants behind postsecondary education inequities. This would be supported by including our adaptation of structural competency for student affairs as an 11th competency that permeates through the other 10 competencies outlined by ACPA and NASPA as standards for the profession (see Figure 1).

Centering the promotion of structural competency across the existing standards would move us toward naming and dismantling how structural violence shapes each of the professional competency focal areas named by ACPA and NASPA (e.g., technology, advising and supporting, and leadership) and addressing how this filters down to the formation of racial disparities. For example, with the ACPA and NASPA [41] competency of technology, access is shaped by broader structural forces. For some, technology can be seen as innocuous, however, BIPOC people disproportionately still lack access to a traditional computer and home internet; increasing the likelihood of student attrition in online, remote, hybrid, and other forms of learning where technology is needed [74,75]. This stems from decades of racist housing policies and practices such as red-lining that still impacts communities of color [76] and contributes to the accumulation of wealth and property in white communities [54,65]. Marshall and Ruane [77] reported that greater access to technology like broadband will advance racial equality, as “the deepest rift in the digital divide is when it comes to race” (para. 5). Therefore, it is not good enough to just integrate technology into student affairs practice, it is important to center race and to be nuanced in addressing the structural/upstream forces that limit BIPOC students from having equitable access to technology.

Introducing a framework of structural competency in student affairs, one informed by CRT’s naming of structural racism and antiblackness, can move us toward humanization and new possibilities [63], necessary for reimagining student affairs practice. We invite higher education and student affairs scholars to test the framework’s efficacy on the ground and refine it. We encourage student affairs practitioners to include structural competency in staff orientations, on-boarding trainings, and local and national professional conferences. We also encourage advisors, department chairs, and deans to adopt this framework in their work. As well, academic journals and organizations can bring greater attention to structural competency via journal Special Issues and themed conferences in student affairs. Our hope is for structural competency to enable the preparation and professional development of student affairs leaders empowered to create more humanizing higher education conditions where BIPOC students are not further harmed by racialized structures, but supported in fully thriving.

Author Contributions

References

- Patton, L.D. Disrupting postsecondary prose: Toward a critical race theory of higher education. Urban Educ. 2016, 5, 315–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, J. Descendant of University of Missouri Founder Creates Slavery Atonement fund. Diverse Issue. 2008. Available online: http://diverseeducation.com/article/10697/ (accessed on 14 October 2022).

- Powell, A. Dual Message of Slavery Probe: Harvard’s Ties Inseparable from Rise, and Now University Must Act. The Harvard Gazette. 2022. Available online: https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2022/04/slavery-probe-harvards-ties-inseparable-from-rise/ (accessed on 22 September 2022).

- Wilder, C.S. Ebony and Ivy: Race, Slavery, and the Troubled History of America’s Universities; Bloomsbury Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J.D. The Education of Blacks in the South, 1860–1935; University of North Carolina Press: Chapel Hill, NC, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Minor, J.T. Segregation Residual in Higher Education: A Tale of Two States. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2008, 45, 861–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund Inc. as Amici Curiae Support of Respondents Students for Fair Admissions v. University of North Carolina, et al., (no. 21-707). 2022. Available online: https://www.naacpldf.org/wp-content/uploads/21-707-Amicus-Brief-of-NAACP-Legal-Defense-and-Educational-Fund-Inc.-et-al.pdf (accessed on 9 December 2022).

- Boggs, A.; Meyerhoff, E.; Mitchell, N.; Schwartz-Weinstein, Z. Abolitionist University Studies: An Invitation. n.d. Available online: https://abolition.university/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/Abolitionist-University-Studies_-An-Invitation-Release-1-version.pdf?df5dc0&df5dc0 (accessed on 7 December 2022).

- Poon, O.A. Ending white innocence in student affairs and higher education. J. Stud. Aff. 2018, 27, 13–21. Available online: https://www.asgaonline.com/Uploads/Public/JOUF_JOSA_v27-2017-18.pdf (accessed on 22 September 2022).

- Song, J. UC System Divests $30 Million in Prison Holdings Amid Student Pressure. LA Times. 2015. Available online: https://www.latimes.com/local/education/la-me-uc-divestment-prisons-20151226-story.html (accessed on 22 September 2022).

- Alexander, M. The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness; The New Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Dancy, T.E.; Edwards, K.T.; Earl Davis, J. Historically white universities and plantation politics: Anti-Blackness and higher education in the Black Lives Matter era. Urban Educ. 2018, 53, 176–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, W.G.; Bok, D. The Shape of the River: Long-Term Consequences of Considering Race in College and University Admissions; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Harper, S.R. Niggers no more: A critical race counternarrative on Black male student achievement at predominantly white colleges and universities. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Educ. 2009, 22, 697–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strayhorn, T.L. College Students’ Sense of Belonging: A Key to Educational Success; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bonilla-Silva, E. Rethinking racism: Toward a structural interpretation. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1997, 62, 465–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Education Trust. Segregation Forever. 2020. Available online: https://edtrust.org/resource/segregation-forever/ (accessed on 18 November 2022).

- Carnevale, A.P.; Van Der Werf, M.; Quinn, M.C.; Strohl, J.; Repnikov, D. Our Separate & Unequal Public Colleges: How Public Colleges White Racial Privilege. 2018. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED594582.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2022).

- California Faculty Association Infograpnic: Declining Black Student Enrollment. 2020. Available online: https://www.calfac.org/infographic-declining-black-student-enrollment/ (accessed on 20 November 2022).

- California State University. Graduation Dashboard. 2020. Available online: https://tableau.calstate.edu/views/GraduationRatesPopulationPyramidPrototype_liveversion/SummaryDetails?iframeSizedToWindow=true&%3Aembed=y&%3Adisplay_count=no&%3AshowAppBanner=false&%3AshowVizHome=no (accessed on 20 November 2022).

- The Campaign for College Opportunity. State of Higher Education for Black Californians. 2019. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED596506.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2022).

- Levine and Ritter. The Racial Wealth Gap, Financial Aid, and College Access. 2022. Available online: https://www.brookings.edu/blog/up-front/2022/09/27/the-racial-wealth-gap-financial-aid-and-college-access/ (accessed on 18 November 2022).

- Carnevale, A.P.; Strohl, J. Separate & Unequal: How Higher Education Reinforces the Intergenerational Reproduction of White Racial Privilege. 2013. Available online: https://1gyhoq479ufd3yna29x7ubjn-wpengine.netdna-ssl.com/wp-content/uploads/SeparateUnequal.ES_.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2022).

- Jayakumar, U.M. Transforming Racial Climate Health on Campus: The Need for Structural Competency, University of California: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2020; Manuscript Submitted for Publication.

- Ledesma, M.C. Complicating the binary: Toward a discussion of campus climate health. J. Committed Soc. Chang. Race Ethn. 2016, 2, 6–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metzl, J.M.; Hansen, H. Structural competency: Theorizing a new medical engagement with stigma and inequality. Soc. Sci. Med. 2014, 103, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, D.E. Killing the Black Body: Race, Reproduction, and the Meaning of Liberty; Vintage Books: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler, M.L.; Link, B.G. Introduction to the special issue on structural stigma and health. Socl. Sci. Med. 2014, 103, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raz, M. What’s Wrong with the Poor? Psychiatry, Race, and the War on Poverty; University of North Carolina Press: Chapel Hill, NC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bradby, H. What do we mean by “racism”? Conceptualizing the range of what we call racism in health care settings: A commentary on Peek et al. Soc. Sci. Med. 2010, 71, 10–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladson-Billings, G. The Dreamkeepers: Successful Teachers of African American Children; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Harper, S.R. An anti-deficit framework for research on BIPOC students in STEM. In BIPOC Students in STEM: Engineering a New Research Agenda; Harper, S.R., Newman, C.B., Eds.; New Directions for Institutional Research; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2010; pp. 63–74. [Google Scholar]

- Ladson-Billings, G. Culturally relevant pedagogy 2.0: A.k.a. the Remix. Harv. Educ. Rev. 2014, 84, 74–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehyle, D. Constructing failure and maintaining cultural identity: Navajo and Ute school leavers. J. Am. Indian Educ. 1992, 31, 24–47. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/24398114 (accessed on 26 September 2022).

- Pope, R.L.; Reynolds, A.L.; Mueller, J.A. Multicultural Competence in Student Affairs; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Jayakumar, U.M. Can higher education meet the needs of an increasingly diverse and global society? Campus diversity and cross-cultural workforce competencies. Harv. Educ. Rev. 2008, 78, 615–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engberg, M.E. Educating the workforce for the 21st century: A cross-disciplinary analysis of the impact of the undergraduate experience on students’ development of a pluralistic orientation. Res. High. Educ. 2007, 48, 283–317. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/25704505 (accessed on 26 September 2022). [CrossRef]

- Engberg, M.E.; Hurtado, S. Developing pluralistic skills and dispositions in college: Examining racial/ethnic group differences. J. High. Educ. 2011, 82, 416–443. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/29789533 (accessed on 26 September 2022). [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S. On Being Included: Racism and Diversity in Institutional Life; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Jayakumar, U.M.; Garces, L.M.; Park, J.M. Reclaiming diversity: Advancing the next generation of diversity research toward racial equity. In Higher Education: Handbook of Theory and Research; Paulsen, M., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 11–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ACPA and NASPA. Professional Competency Areas for Student Affairs Educators. 2015. Available online: https://www.naspa.org/files/dmfile/ACPA_NASPA_Professional_Competencies_1.pdf (accessed on 26 September 2022).

- Chambers, J.; Ratliff, G.A. Structural competency in child welfare: Opportunities and applications for addressing disparities and stigma. J. Sociol. Soc. Welf. 2019, 46, 51–75. Available online: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/jssw/vol46/iss4/5 (accessed on 29 June 2022).

- Homan, P.; Brown, T.H.; King, B. Structural Intersectionality as a New Direction for Health Disparities Research. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2021, 62, 350–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladson-Billings, G. Toward a theory of culturally relevant pedagogy. Am. Educ. Res. J. 1995, 32, 465–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comeaux, E.; Watford, T. Admissions & omissions: How “the numbers” are used to exclude deserving students. Bunche Res. Rep. 2006, 3. Available online: https://bunchecenter.ucla.edu/2012/05/15/bunche-research-report/ (accessed on 14 October 2022).

- Guinier, L. Admissions rituals as political acts: Guardians at the gates of our demographic ideals. Harv. Law Rev. 2003, 117, 113. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, J.L.; Harris, F., III; Delgado, N.R. Struggling to Survive–Striving to Succeed: Food and Housing Insecurities in the Community College; Community College Equity Assessment Lab (CCEAL): San Diego, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Long, B.T.; Riley, E. Financial aid: A Broken bridge to college access? Harv. Educ. Rev. 2007, 77, 39–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barron, N.; Grimm, N. Addressing racial diversity in a writing center: Stories and lessons from two beginners. Writ. Cent. J. 2002, 22, 55–83. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/43442150 (accessed on 14 October 2022). [CrossRef]

- Garcia, R. Unmaking gringo-centers. Writ. Cent. J. 2017, 36, 29–60. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/44252637 (accessed on 26 September 2022). [CrossRef]

- Farmer P., E.; Nizeye, B.; Stulac, S.; Keshavjee, S. Structural violence and clinical medicine. PLoS Med. 2006, 3, 1681–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, D.A. Brown v. Board of Education and the interest-convergence dilemma. Harv. Law Rev. 1980, 93, 518–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crenshaw, K.W. Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanf. Law Rev. 1991, 43, 1241–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, C.I. Whiteness as property. Harv. Law Rev. 1993, 106, 1707–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, R.; Stefancic, J. Critical Race Theory: An Introduction, 2nd ed.; New York University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, T. The disenfranchisement of African American males in PreK–12 schools: A critical race theory perspective. Teach. Coll. Rec. 2008, 110, 954–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladson-Billings, G.; Tate, W.F. Toward a Critical Race Theory of Education. Teach. Coll. Rec. 1995, 97, 47–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solórzano, D.G. Images and words that wound: Critical race theory, racial stereotyping, and teacher education. Teach. Educ. Q. 1997, 24, 5–19. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/23478088 (accessed on 26 September 2022).

- Stovall, D. School leader as negotiator: Critical race theory, praxis and the creation of productive space. Multicul. Ed. 2004, 12, 8–12. [Google Scholar]

- Yosso, T.J.; Smith, W.A.; Ceja, M.; Solórzano, D.G. Critical Race Theory, racial microaggressions, and campus racial climate for Latina/o undergraduates. Har. Ed. Rev. 2009, 79, 659–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crenshaw, K.W. Twenty years of critical race theory: Looking back to move forward. Conn. Law Rev. 2011, 43, 1253–1353. Available online: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/law_review/117 (accessed on 26 September 2022).

- Dumas, M.J.; Ross, K.M. Be real Black for me: Imagining BlackCrit in education. Urban Educ. 2016, 51, 415–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, C.A. From morning to mourning: A meditation on possibility in Black education. Equity Excell. Educ. 2021, 54, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, C.A.; Wood, D. Rupturing the Black-White Binary: Critical Theory, Mourning, and Pathways to Racial Justice. Phil. Theory High. Edu. 2023, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Lipsitz, G. The Possessive Investment in Whiteness; Temple University Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Guinier, L. From racial liberalism to racial literacy: Brown v. Board of Education and the interest-divergence dilemma. J. Am. Hist. 2004, 91, 92–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohli, R.; Dover, A.G.; Jayakumar, U.M.; Lee, D.; Henning, N.; Comeaux, E.; Nevárez, A.; Hipolito, E.; Carreno Cortez, A.; Vizcarra, M. Toward a Healthy Racial Climate: Systemically Centering the Well-being of Teacher Candidates of Color. J. Teach. Educ. 2022, 73, 52–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sealey-Ruiz, Y. Building racial literacy in first-year composition. Teach. Engl. Two Year Coll. 2013, 40, 384–398. [Google Scholar]

- Wantanabe, T. UC Housing Crisis Forces Students Into Multiple Jobs to Pay Rent, Sleeping Bags and Stress; Los Angeles Times: El Segundo, CA, USA, 2022; Available online: https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2022-09-26/college-housing-shortage-pushes-students-into-crisis-as-most-uc-classes-start-up (accessed on 22 September 2022).

- Rothstein, R. The Color of Law; Liveright Publishing Corporation: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Schlichtman, J.J.; Patch, J.; Hill, M.H. Gentrifier; University of Toronto Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Jayakumar, U.M.; Adamian, A.S. Toward a critical race praxis for educational research: Lessons from affirmative action and social science advocacy. J. Committed Soc. Chang. Race Ethn. 2015, 1, 22–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitman, K.L.; Exarhos, S. The New Jim Crow in higher education: A Critical race analysis of postsecondary policy related to drug felonies. JCSCORE 2020, 6, 32–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atske, S.; Perrin, A. Home Broadband Adoption, Computer Ownership Vary by Race, Ethnicity, in the U.S. Pew Research Center. 2021. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/07/16/home-broadband-adoption-computer-ownership-vary-by-race-ethnicity-in-the-u-s/ (accessed on 14 October 2022).

- National Urban League. New Analysis Shows BIPOC Students More Likely to Be Cut from Online Learning. 2022. Available online: https://nul.org/news/new-analysis-shows-students-color-more-likely-be-cut-online-learning (accessed on 14 October 2022).

- Skinner, B.; Levy, H.; Burtch, T. Digital redlining: The relevance of 20th century housing policy to 21st century broadband access and education. EdWorkingPaper 2021, 21, 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, B.; Ruane, K. How Broadband Access Advances Systemic Equality; American Civil Liberties Union: New York, NY, USA, 2021; Available online: https://www.aclu.org/news/privacy-technology/how-broadband-access-hinders-systemic-equality-and-deepens-the-digital-divide (accessed on 14 October 2022).

| Competency 1 | Recognizing how racialized structures shape student-practitioner relations and interactions |

| Competency 2 | Developing racial literacies |

| Competency 3 | Rearticulating “cultural” presentations aligned with deficit assumptions, in structural terms |

| Competency 4 | Observing and re-imagining structural interventions that resist white normativity |

| Competency 5 | Developing structural humility toward an ongoing critical race praxis |

| Competency 6 | Taking a structural intersectionality approach |