The Evolution of Sustainability as a Modern Concept

The concept of sustainability can found in the oral histories of indigenous cultures. For example, the Native American Haudenosaunee, the Iroquois Confederacy, included a version of sustainability, the ‘Law of the Seventh Generation’ in their Great Law. According to this, before any major action was undertaken, its potential consequences on the seventh generation had to be considered. For a species that at present is only 6,000 generations old and whose current political decision-makers operate on time scales of months or a few years at most, the thought that other human cultures have based their decision-making systems on time scales of many decades seems wise but perhaps inconceivable in the current political climate.

Our Common Future (1987), the World Commission on Environment and Development report, is widely credited with popularizing the concept of sustainable development. It defines sustainable development in the following ways…

- …development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.

- … sustainable development is not a fixed state of harmony but rather a process of change in which the exploitation of resources, the orientation of technological development, and institutional change are consistent with future and present needs.

In the present, sustainability is generally defined in the same way as the World Commission’s first wording – meeting the needs of present generations without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their needs. Further, sustainability is seen as having three main facets, often called the “pillars of sustainability” – environmental sustainability, economic sustainability, and social sustainability. This text focuses primarily on environmental sustainability, but incorporates aspects of economic sustainability and social sustainability because these three forms of sustainability are interwoven and interdependent. Although environmental sustainability could readily be achieved in the absence of humans, once humans are in the mix, achieving environmental sustainability requires some measure of human well-being, which in turn requires economic and social sustainability.

Useful Concepts Related to Sustainability

The ecological footprint (EF) was developed in 1990 by Canadian ecologist and planner William Rees and Swiss sustainability advocate Mathis Wackernagel. It is an accounting tool that uses the land as the unit of measurement to assess per-capita consumption, production, and discharge needs. It starts from the assumption that every category of energy, material consumption, and waste discharge requires the productive or absorptive capacity of a finite area of land or water. If we determine all the land requirements for all categories of consumption and waste discharge by a defined population, the total area represents the ecological footprint of that population on Earth, whether or not this area coincides with the population’s home region. Land area is a useful measure because land is literally the foundation and source for the goods and services humans receive from the environment and without which life would not be possible.

Ecological footprint analysis can tell us in a easily grasped manner how much of the Earth’s environmental functions are needed to support human activities. It also makes visible the extent to which consumer lifestyles and behaviors are ecologically sustainable. According to the Global Footprint Network, the ecological footprint of the average person living in the US in 2019 was – conservatively – 5.1 hectares of productive land per capita. By their calculations, humanity exceeded earth’s ecological carrying capacity in 1970, and in 2019 needed about 1.7 Earths in order to support current consumption, sustainably.

The precautionary principle is another important concept in environmental sustainability. The Wingspread Statement, a 1998 consensus statement by an international group of researchers, policy makers, and advocates, characterized the precautionary principle: “When an activity raises threats of harm to human health or the environment, precautionary measures should be taken even if some cause and effect relationships are not fully established scientifically.” For example, if a new pesticide chemical is created, the precautionary principle would dictate that we presume, for safety, that the chemical may have potentially negative consequences for the environment and/or human health, even if such consequences have not been proven yet. In other words, it is best to proceed cautiously in the face of incomplete knowledge about something’s potential harm.

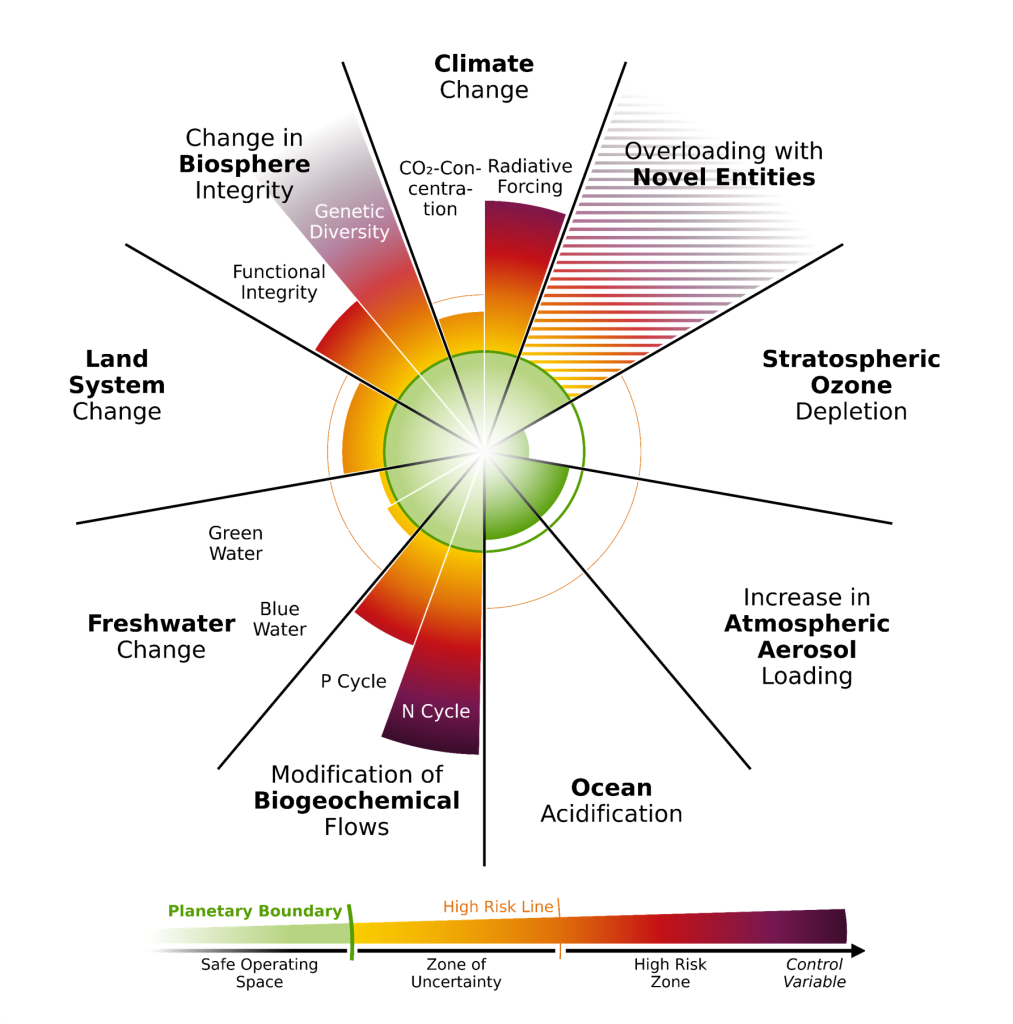

Planetary boundaries are limits to particular aspects of the planetary conditions (including temperature, and nutrient levels, for example) required for the functioning of life on Earth as we presently know it (Fig 1). The original 9 limits were proposed in 2009 by a group of environmental scientists; they include both familiar items such as ozone depletion that causes the so-called “ozone hole” and much less familiar items such as ocean acidification and radiative forcing. All are considered crucial to the planet’s ability to support life. By 2023, 6 of the 9 boundaries were considered to have been crossed. We will address individual planetary boundaries in the chapters to which they relate. More information on the planetary boundaries model and information on the status of each is here.

The nine original proposed planetary boundaries and their status in 2023. For example, stratospheric ozone – the high-atmosphere ozone that protects life from high UV radiation levels – is within the safe operating space for life as we know it – below the green line – but radiative forcing – the balance between warming and cooling processes on the planet – is dangerously out of balance. By Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK) CC BY 4.0

A number of additional variables have been suggested as planetary boundaries, including soil health. Numeric limits for the various zones of safety have not yet been set for novel entities (synthetic chemicals, genetically modified or synthetic organisms, and any other human-created additions to the planet), but scientists are certain that, whatever the safe limit may be, it has been passed.

The UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs ) is a set of 17 goals designed to ensure that environmental, social, and economic sustainability is considered, and regularly assessed, as nations undertake development and ongoing governance. They cover all aspects of sustainability. The goals are part of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, that was created in 2015 and adopted by all nations.

Video 1. Watch the short video that quickly introduces the UN Sustainability Development Goals.

Video 1. Watch the short video that quickly introduces the UN Sustainability Development Goals.Each development goal has multiple targets that provide ways to measure progress toward the goal. For example, the first target for the Clean Water and Sanitation goal is By 2030, achieve universal and equitable access to safe and affordable drinking water for all. Overall, 169 targets are identified. Reports are produced annually to review progress. You can read the 2023 report here.

Some Indicators of Global Environmental Stress

Forests — Deforestation remains a main issue, with the greatest forest loss occurring in tropical forests. Between 2001 and 2015, an estimated 63% of tree-cover loss occurred in order to create open land for cattle grazing.

Soil — As much as 33% of the Earth’s vegetated surface is now at least moderately degraded, according to a 2015 report coauthored by the FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations). Trends in soil quality and management of irrigated land raise serious questions about longer-term sustainability.

Fresh Water — Some 26% of the world’s population lacks access to safe water according to the 2023 UN World Water Development Report, and 46% lack access to safe sanitation.

Marine fisheries — According to a 2024 FAO report based on 2021 data, although 77% of the the weight of harvested fish came from sustainably-managed stocks, only 62.3% of marine fish stocks were being harvested within sustainable levels.

Biodiversity — World Wildlife Fund’s 2024 Living Planet Report 2024 stated that the size of the global wildlife populations declined an average of 73% between 1970 and 2020. Extinction rates, already significantly higher than historical trends, are predicted to rise sharply under climate change. Under current climate trends, more than 95% of coral reefs are predicted to be lost by the end of the century.

Atmosphere — In 2024, planetary temperatures were more than 1.5ºC higher than historical averages, the first time the world crossed a boundary that nations agreed to try to avoid crossing, in order to protect human and environmental health from rising temperatures.

Toxic chemicals — Over 350,000 chemicals may now be in commercial use. The most protective legal statutes in the world do not require any testing for cumulative effects of chemicals that commonly co-occur in the environment. Older, so-called “persistent” organic pollutants, microplastics, and newer “forever chemicals” are now so widely distributed by air and ocean currents that they are found in the tissues of people and wildlife everywhere.

Hazardous wastes — Pollution from heavy metals, especially from their use in industry and mining, also creates serious health consequences in many parts of the world. In addition, incidents and accidents involving uncontrolled radioactive sources continue to increase, and particular risks are posed by the legacy of contaminated areas left by military activities involving nuclear materials.

Waste — Domestic and industrial waste production continues to increase in both absolute and per capita terms worldwide. In the developed world, per capita waste generation has increased threefold over the past 20 years; in developing countries, waste generation will likely double during the next decade. However, the level of awareness regarding the health and environmental impacts of inadequate waste disposal remains relatively poor; poor sanitation and waste management infrastructure are still one of the principal causes of death and disability for the urban poor.

Media Attributions

- PBs2023.w wh backgr © Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- SDGs video