1 1.3 Environmental Economics and the Role of Environmental Regulation in Free Markets

This is a text about science, but applied science is often used to create environmental regulations, and environmental regulations are often needed to protect environmental health. Nevertheless, environmental regulations are often subject to attack by people who believe they are an economic mistake that burdens businesses and raise prices for consumers.

Free markets

A free market exists when people can freely choose what they want to buy or sell and can pay or receive a fair price for it. In a free market, all goods and services are privately owned; the benefits and costs of the goods and provision of service are received (benefits) and borne (costs) only by the owners of the goods or the providers of the services, who can protect their ownership (theft can be prevented). Consumers have enough information to know whether they want to pay the offered price, and there is competition among providers.

Adam Smith, a Scottish economist and philosopher, wrote An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (often shown just as The Wealth of Nations) in 1776, just as the US was becoming a nation. In it, he suggested that individuals acting only for their own self-interest in buying and selling could still benefit society at large. He suggested that free markets were one way this could happen. Economists maintain that true free markets – free markets that meet all the requirements to be called free markets – could result in fair prices in the absence of regulation.

Note that fair prices are not the same as low prices, or convenient prices. Rather, they are prices that accurately reflect the cost of the good or services that consumers are willing to pay and that owners are willing to offer. If the owner sets the price too high, consumers will have enough information to understand that the prices is higher than they need to pay, and there will be competitors to offer lower prices, but only to the point that owners can still make the profits they need in order to continue to produce the items involved. Prices, in the long run, will support the continued existence of owners, who invest money to provide the goods and services, but will not rise far above that point for long, because competition will bring them back down. Owners are driven to be efficient in their production of goods and services, so that they may become cheaper over time and consumers that make themselves aware of alternative prices can benefit from that increased efficiency. If a good or service is rare or difficult to provide, then owners will only be able to ask higher prices if item is attractive enough that consumers will pay high prices, and consumers will understand the situation well enough to choose whether to pay high prices.

As in all good stories, the devil is in the details. Let’s look first at the requirement for private ownership of goods and services. Economists term this universality because, in a free market, all goods are privately owned.

Private, Public, Club, and Common-Pool Resources

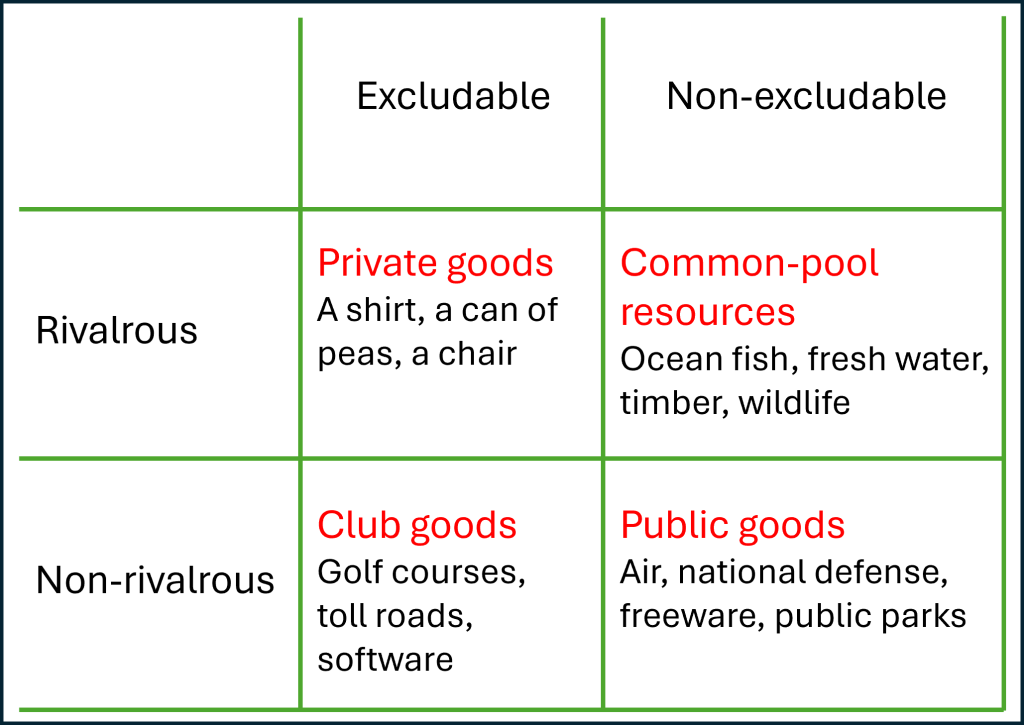

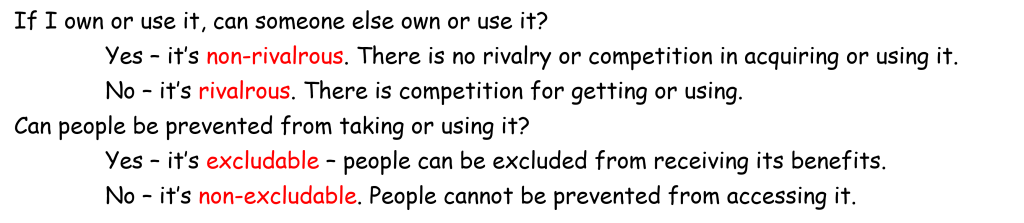

Economists divide goods (things, mostly) up into categories depending on whether there is competition for their use (usually, no one competes for air, but lots of people compete for trees that produce expensive timber), and whether or not it’s possible to prevent people from accessing the goods (not really, for air; possibly, but not always, for the trees). Figure 1 shows the formal names given to the resulting categories.

Some of the lines among categories can become blurry under some circumstances. Public, non-toll roads are typically considered to be public goods for which people do not compete. Taxes pay for the roads and everyone can use them. But any city at rush hour demonstrates that, if there isn’t competition, precisely, easy access is certainly not available! Public parks that are highly popular can monitor user numbers and close the park (if access can be controlled) above certain user levels.

Obviously, lots of goods and services are not private. Many things classified as natural resources or ecosystem services are not privately owned or controlled. Laws and regulations can create private ownership for some resources. In the US, the soil and plants on private land are owned by the landowner, but wildlife is not. In other parts of the world, community ownership of forests and wildlife is common; depending on the definition of community ownership and the strength of control of access, this may or may not be similar to private ownership.

Not all natural resources are readily privatized. Although nations control the seas within 200 km of their borders (their exclusive economic zones – EEZs), the open ocean is a commons – a common-pool resource. Fish that inhabit the open ocean are thus also a common-pool resource. Fish that migrate across EEZs and the open ocean are even more complicated, as they may be considered both privatized through fishing regulations in the EEZs and common-pool resources on the high seas, and the fishing regulations in different EEZs may protect them differently from overfishing, while they may be subject to no treaties in the open ocean. Treaties among nations can, in theory, regulate fishing there, but not all nations sign such treaties, monitoring can be difficult or impossible, and enforcement requires willing and cooperative partners. Minerals from the deep ocean floor are a common-pool resource for which treaty discussions are currently very dynamic.

Some aspects of freshwater are often not privatized. The ability to withdraw water for industrial, municipal, agricultural, and household use is often legally controlled, but these laws may run into problems dealing with surface water and ground water, because these are often more closely connected than the laws recognize. Access to swim or boat on water may be controlled by a property owner for a pond or lake entirely within a single property, but may be more complicated if multiple property owners, towns, states, or nations are involved. Access to discharge pollution into water is similarly complicated by jurisdictional issues. Pollution that enters the water at one point can spread to other points that may not have jurisdiction to prevent the pollution at the source. National regulations and international treaties may be required to control the problem.

Because air is not usually subject to competition, and is not excludable, it is considered a public good. Air pollution can be regulated through regulations of the sources of air pollution, but air pollution, like water pollution, can cross jurisdictional lines. National-level regulation can maintain air quality within a nation, but international treaties are needed to maintain air quality when air pollution cross international lines. Market-based mechanisms called cap-and-trade agreements exist for some air pollutants, notably the main precursors for acid rain – sulfur dioxide and NOx – and carbon in the form of CO2 equivalents. In other cases, laws are directly regulatory – like water laws – setting limits and imposing penalties.

Externalities are Failures in the Exclusivity of Costs and Benefits to Owners

Under free-market conditions, all the benefits of having a good or providing a service accrue to the owner, and all the costs of creating the good or providing the service likewise are borne by the owner. In the real world, things are often not so neat.

Even with something as simple as a shirt or a can of peas, pollution from fabric dyes or erosion from agriculture may enter air or water, creating a burden borne by members of the public, who support pollution monitoring and enforcement. If regulations recoup the cost through permitting fees and penalties, then the public is made whole and does not pay to clean up after the private owners. But often, this is not the case. Monitoring may not occur at all, or may have gaps in coverage. Enforcement may be understaffed. Regulations may not exist in the first place, so that neither monitoring nor enforcement exists.

An externality is a cost or benefit that arise as a result of provision of a good or service but is not received by or borne by the owner. Not all externalities are negative. If your neighbors keep beautiful homes and lovely gardens, your property values may rise, as a result, providing you with a positive externality. If one property owner along a lake or river restores shoreline wetlands that improve water quality, all users of the lake, and downstream users of the river, benefit.

Externalities exist with many private goods and services, but are particularly likely to exist when natural resources are harvested or extracted, because of the complicated connections among the components of the natural world. The hunter who kills a wolf in a legal hunt affects the deer populations in the area, which in turn affects the vegetation, which may affect timber availability. The logger who extracts timber from a forest may create erosion that affects water quality, reduce water filtration at the harvest site, and alter the composition of wildlife, fish, and plants in the vicinity. In theory, externalities can be prevented by laws that protect environmental health, but legal protection and enforcement are often incomplete, and externalities are common, as a result.

Perfect Information is Rarely Available

Because information about externalities is often unavailable, consumers cannot always make informed decisions about what to purchase from whom, which also defeats the requirement for so-called perfect information in a free market. Non-economists can be forgiven for assuming that perfect information is the same as complete information, but consumers don’t need to know absolutely everything about goods in order to make informed decisions. We probably don’t need to know the name of the person who delivered the peas to the store, for example. But consumers may want a wide range of information about environmental impacts, economic, and societal impacts before they decide what to purchase, and from whom. Information can be required by law, but often is not, and enforcement of the requirements to provide accurate information may also be insufficient.

Environmental Regulations Are Often Required, to Meet Free-Market Conditions

A common accusation levelled against environmental regulations and regulators is that they are interfering with free markets. People often know that free markets can operate “without regulation,” but often do not know about the many requirements that must be met in order for a free market to exist, in the first place. Common-pool resources, theft and poaching, externalities, lack of information, and monopolies all defeat free markets, and all can be addressed, if imperfectly, through regulation. Thus, environmental regulations can be necessary for creating free markets. Without such protections, the public is left with the cost of cleaning up environmental harm or is deprived of opportunities and services that cannot be replaced.

Costs for clean-up and loss of ecosystem service are separate from the costs of shirts and peas and timber and fish. As a result, people may not make the link between the low cost of timber or a shirt and the high price for drinking water or the loss of wildlife. One phrase used in environmental economics that makes this link more visible is “polluter pays.” But when harm is not as obvious as dirty air or water, it may still be hard for people to see connections between environmental regulation, environmental health, and fair prices for goods and services.

Not all regulations support free-market conditions. Some regulations are created for other purposes, such as tariffs that are used for political reasons. But even regulations intended to ensure that costs to prevent environmental harm stay with the providers of goods and services may be imperfect. For example, laws may impose weak penalties that may decrease pollution somewhat, but not to the level needed to prevent harm. The process of creating environmental regulations thus requires firm foundations in both environmental science and environmental economics.

Media Attributions

- Table of goods

- Rivalrous and excludable definitions © Vicky Meretsky is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

Ecosystem services are processes that occur naturally that benefit humans. Provisioning services include providing food, water, and clothing and building materials. Regulating services include water and air purification, prevention of erosion, pollination, and flood reduction. Cultural services include recreational opportunities, opportunities for meditation and veneration, and provision of culturally important icons such as totem animals and sacred sites.