Who Decides What’s for Dinner?

Bon Appétit

Lizzie Patterson

Since I was 13, when I began studying French, I have continuously been introduced to one, ceaseless theme: French food, and its food system, is superior. The French take pride in their gastronomical history; food, wine, and cuisine are deeply ingrained in their culture. I became immersed in the food culture while studying abroad in a small city in southern France, Aix-en-Provence. In Aix, the bistros and cafés that lined the streets and the daily markets provided a stark contrast to the food system that I was familiar with in the United States. Instead of fast-food restaurants on every corner or arena-sized Krogers, French cities house small mom-and-pop restaurants and convenience stores, local bakeries and specialty stores, and daily farmers markets. Rather than a large fridge to house weeks’-worth of groceries, my petit French apartment held a mini-fridge smaller than the one I owned my freshman year of college, holding 4 days’ worth of groceries, maximum. The dissimilarity between the French and American food systems are so distinct that it became one of my largest culture shocks while there. Yet, it also made me question why, and how, are the two food systems are so different, and if French food system truly is superior?

The superiority-complex that the French have about their food system, from the agricultural production to consumption, stems from the dominance of cuisine in French daily life. On the surface, the food systems between the United States and France don’t strongly differ, especially in terms of economic production. In the United States, agricultural output from American farms generated $136.1 billion into the economy in 2019 (USDA, 2020). In comparison, France was the largest agricultural producer in Europe in 2015, contributing 116.3 billion euros ($129.2 billion[1]) to the French economy (Ministère de l’Agriculture et de l’Alimentation, 2015). However, in France, eating is not a task but rather a pass-time to spend with loved ones, an opportunity to enjoy great cuisine and cherish the quality of the food on their plate. Camas Davis (2018), author of Killing It: An Education, argues that while both the US and French systems are industrialized to serve consumers, the French consumer base is more invested in their food system and value the preservation of traditional food production, supporting local farmers, and sustainability, thus incentivizing information transparency, government regulations, and higher quality production. In contrast, The United States lacks a food culture that prioritizes quality cuisine, instead favoring cheap and low-quality food. The French food system serves as a foil against the United States’; influenced by consumers support for industry transparency, and quality standards, French consumers support a food system that upholds their cultural emphasis on food. Similar values have not been prioritized in the United States, leaving consumers unaware of the environmental, nutritional, and industrial implications of buying mass-produced, cheap food and failing to enjoy the simple pleasures of high-quality cuisine.

Eat Local

One of the supermarkets in Bloomington, Indiana, Fresh Thyme, has a small section of dry-goods dedicated to “Indiana Grown” products. The shelf space houses a wide range of products from jams and preservatives to spice mixes and popcorn kernels; all priced slightly higher than their generic competitors, but featuring a seal promising a commitment to supporting local farmers and businesses. Fresh Thyme’s “Indiana Grown” marketing reflects a larger trend supporting local products; surveys have found that 78% of American consumers would pay more if they had better access to local products in their supermarket. Despite the rise in popularity for locally sourced food, there is no legislation to support local farmers’ transition into large retailers or a legal definition for “local”, leaving most retailers to consider local being within 100-miles or at least within the state.

In France, the fight for locally sourced food doesn’t start with reserving shelf space but from the French National Assembly. In 2016, the upper parliamentary chamber passed a bill requiring 40% of food served in “collective restaurants”, defined as school, hospital or other communal cafeterias, to be sourced locally. The proposed law provokes a radical change to the food system, emphasizing the importance of locally sourced food and environmental sustainability from a governmental body. While there isn’t a specified guideline for “locally sourced”, the recommendations were estimated to be 19 miles for fresh produce and 63 for processed food, all in an attempt to help lower France’s carbon emissions from the agricultural industry by 12% (McNamara, 2016). The legislative support reflects a bigger cultural commitment to environmental sustainability and supporting local farmers that is favored by consumers. Multiple studies have found that traditional food distribution produces 5 to 17 times more CO2 emissions than locally produced food, and transportation and final delivery accounts for 16% of all greenhouse gas emissions from the food production supply chain (Cho, 2012). By incentivizing the use of locally sourced food, French consumers decisions continue to improve sustainability practices and the food system as a whole.

In the United States, despite the rise in “locally” sourced food, the government continues to lack any sort of regulation on local agriculture and sustainability initiatives. In addition, industries continue to find new ways to outsource cheap food and take advantage of loosely defined sourcing standards, which agricultural advocates argue “tend to prize large operations that are at odds with consumers’ definitions of local” (Wells, 2017). The relaxed definition of local led to $239 million invested into local label marketing on packaged goods in 2019 (Mullen, 2019), while food still travels and average of 1,494 miles before it finally arrives at American households (Khan, 2018). Thus, while the trend for local food rises, consumers are ignorant to the realities of the American food system that doesn’t receive the benefits from local agriculture.

The Price of High Quality

The fight to support local food is not a new phenomenon in France, the presence of farmers markets and legislative support for small farmers is a cultural norm. The French have opposed globalization of the food system and continue to favor local farmers markets and fresh, high-quality food. “Traditional, high-quality food remains an important part ofFrench culture, and France’s defense of its ‘gastronomical sovereignty’ is itself a tradition” (de Boisgrollier, 2005). In October 2018, the French Parliament enacted more food legislation that would protect the quality of food and promote sustainability. Included was legislation requiring clear origin labeling for honey, “thereby ensuring consumers are better informed about the origin of honey composed of blends from different countries” (Gouvernement français). The legislation emphasizes the importance of high-quality food in French gastronomical culture, something that is commonly ignored by American consumers. In the same Bloomington Fresh Thyme advertising “Indiana Grown” products is a section of retail space dedicated to 10 different varieties of honey. Of the 10, only one specifically brands itself as “American Honey” with no further information on where in the United States the honey is produced. Only by further examination can it be found that 4 of the 10 different honey brands sold are American, the rest are imported from countries such as Brazil or Mexico.

An average American consumer is probably failing to question the source of their honey, or even the quality. However, the honey industry is another example of lack of transparency to American consumers. 75% of honey sold in the United States is altered and is not technically honey, due to inclusion of artificial sweeteners such as high fructose corn syrup or the removal of pollen. The alteration of honey makes the products cheaper for American consumers, but it creates false advertising while also hurting American beekeepers and honeybee populations, which continue to decline by 30-50% every year (Beekeeper’s Naturals, 2018). The cheap and mass-produced honey threatens the quality and sustainability of the product. Honey is not the only food product facing this threat. Molecular biologist Henry Klee analyzed the flavor compounds of different tomato varieties to find that American consumers have compromised flavor and quality for cheap and year-round access to tomatoes, and the trend is similar for other produce such as strawberries or blueberries (Schatzker, 2017).

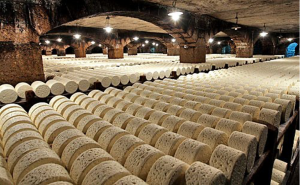

American demand for year-round produce, rather than seasonality, as well as the USDA’s regulations focused on safety rather than quality, has led to the decline in quality. In France, the AOC (Appellation d’Origine Contrôlée) is a government agency that regulates the quality of livestock, agriculture, and other food products (Belluz, 2016). For example, Roquefort, a blue cheese made from sheep milk produced in the southern Occitanie region, can only be produced by following strict guidelines. Fresh, unpasteurized milk must be collected from grazing Lacaune sheep and be aged in naturally formed cliffs overlooking the village of Roquefort (Castello). The end result is a creamy cheese, that despite its expense, is richer and more flavorful than similar cheeses. The regulations from the AOC not only uphold the gastronomical excellency but protect the cultural traditions of French specialty foods.

French government regulations and emphasis on food quality serve as another foil to the to the food system in the United States, where preservation of quality ceases to exist. Despite the advantage of high-quality food, American cultural emphasis is placed on personal freedoms. Creating a government agency that regulates food production puts pressure on industries and removes opportunities to find cheaper alternatives for consumers. Fast, cheap food is engrained in American culture, and regardless of trends pointing to consumers wanting higher-quality food, consumers still lack options or access to resources that allow them to make informed decisions.

A Fight for a Better Food System

Sébastien Windsor, president of the French Chambers of Agriculture, claims that the preservation of French food culture “is not about nationalism. It is about supporting a system that protects [France’s] countryside, and better-quality produce” (Bohlen, 2015). The contrast in attitudes and government support between France and the United States highlight the different role food plays in each culture. French consumers are continuously incentivized to support local farmers at city markets, buy high-quality, seasonal produce, and advocate for sustainable practices in the food system in order to preserve their culture and countryside. The measures have proven successful, with France leading food sustainability efforts in the European Union, largely due to the government’s transparency and “holistic approaches to food loss, water management, and climate change mitigation, and its positive nutrition indicators” (Barilla Center).

The successful efforts in France present a unique opportunity for American consumers. In the United States, 75% of consumers have said that sustainability efforts play a large factor into their food choices (Friedman, 2017). However, unlike efforts made in France by policymakers and businesses, consumers lack education on how to make more sustainable choices. In France, mass public education is ingrained in food culture, such as the “Fruits et Légumes Moches” (Ugly Fruits and Vegetables) campaign launched by Intermarché in French supermarkets in 2014, which marketed unsold food products for a discounted price to reduce the 40% of produce that is wasted (Beaunache, 2016). The campaign reflects the public knowledge that is available to French consumersto improve the food system and support French agriculture. In contrast, the same information available to French consumers is not available to Americans. Only recently has food waste become publicized within the United States, and not on a large scale like Intermarché’s campaign. If 75% of American consumers wish to make more informed and sustainable decisions, the food system fails to advertise ways to do so and instead continues to maintain operations that do not reflect consumer desires.

In reality, the cultural differences between the food systems of France and theUnited States have no reason to differ as significantly as they do. Both countries have thriving agricultural industries and numerous resources to support local farmers and sustainable practices. However, through comparative analysis of the two food systems, it is clear that French consumers have more transparent access to the environmental effects of the food system and the compromised quality from globalized food trade. Thanks to legislation and marketing practices, French consumers continue to be incentivized to shop locally, uphold the standards of cultural excellence, and support a food system that lead sustainability efforts during the threat of climate change.

If the same resources were as widely accessible in the United States, American consumers would undoubtedly support similar initiatives in their own food system. Even if it means a minor change in seasonal produce accessibility or slightly raising prices, American consumers have made it clear that they want to support practices that improve sustainability and the quality of agricultural products. Yet, Cultural emphasis on cheap, mass-produced, and low-quality food is upheld by lack of government interference and control that the agricultural industry has on consumer choices. While these reflect American cultural values of personal freedoms and easy convenience, American consumers’ desires and wishes are shifting. Thus, transparency of food quality and sustainability initiatives to consumers would likely result in a change in action that would be comparable to actions taken in France.

[1] This calculation uses the average EURO to USD conversion rate from 2015 of 1.1108

References

“Ag and Food Sectors and the Economy.” Economic Research Service, United States

Department of Agriculture, 6 Nov. 2020, https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/ag-and-food-statistics-charting-the-essentials/ag-and-food-sectors-and-the-economy/#:~:text=Agriculture%2C%20food%2C%20and%20related%20industries,about%200.6%20percent%20of%20GDP.

“Achieving a Balance in Trade Relations in the Agricultural Sector and Healthy and Sustainable Food.” Gouvernement.fr, www.gouvernement.fr/en/achieving-a-balance-in-trade-relations-in-the-agricultural-sector-and-healthy-and-sustainable.

Belluz, Julia. “Why fruits and vegetables taste better in Europe.” Vox, 12 Feb. 2016,

https://www.vox.com/2016/2/12/10972140/fruits-vegetables-taste-better-europe.

Beunaiche, Nicolas. “Lutte contre le gaspillage: Les produits moches servent-ils vraiment à

quelque chose?” 20 Minutes France, 12 Jan. 2016,

https://www.20minutes.fr/societe/1764779-20160113-lutte-contre-gaspillage-produits-moches-servent-vraiment-quelque-chose.

Bohlen, Celestine. “Protecting the Farmers of France.” The New York Times, 10 Apr. 2015,

https://www.nytimes.com/2015/08/11/world/europe/protecting-the-farmers-of-france.html.

Cho, Renee. “How Green is Local Food?” State of the Planet, Earth Institute of Columbia

University, 4 Sep. 2012, https://blogs.ei.columbia.edu/2012/09/04/how-green-is-local-

food/.

Davis, Camas. “How is the food system in the U.S. different from Europe?” Quora, 18 Oct.

De Boisgrollier, Nicolas. “Why the French Love Their Farmers.” The Brookings Institute, 15 Nov.

2005, https://www.brookings.edu/opinions/why-the-french-love-their-farmers/.

“France Leads the World on Food System Sustainability.” Barilla Center for Food & Nutrition,

https://foodsustainability.eiu.com/france/.

Friedman, Ally. “In a Broekn Food System, Consumers Have More Power Than They Realize.”

World Resources Institute, 10 Feb. 2017, https://www.wri.org/blog/2017/02/broken-food-system-consumers-have-more-power-they-realize.

Khan, Hina. “Small Farmers Need Our Support. Here’s What We Can Do.” The Farm Project, 25

Oct. 2018, https://www.thefarmproject.com/blog/small-farmers-need-our-support/

McNamara, Eva. “New Law Could Change France’s Food System for the Better.” Foodtank,

Jan. 2016, https://foodtank.com/news/2016/01/new-law-could-change-frances-food-system-for-the-better/.

Mullen, Caitlin. “People want to buy ‘local’ food, but they’re not sure what it means.” The Business Journals, 10 May 2019, https://www.bizjournals.com/bizwomen/news/latest-news/2019/05/people-want-to-buy-local-food-but-theyre-not-sure.html?page=all.

“Overview of French Agricultural Diversity.” Ministère de l’Agriculture et de l’Alimentation, 22 Sept. 2015, https://agriculture.gouv.fr/overview-french-agricultural-diversity#:~:text=France%20has%20the%20biggest%20utilized,third%20in%20pig%20meat%20production.

“Roquefort.” Castello, https://www.castellocheese.com/en-us/cheese-types/blue-mold-cheese/roquefort/.

Schatzker, Mark. “Tomato flavor is broken. Can it be fixed?” Vox, 20 Feb 2017, https://www.vox.com/science-and-health/2017/1/27/14414538/supermarket-tomatoes-taste-fix-science.

“Something Rotten is Going on in the Honey Industry. Even Netflix Knows it.” Beekeeper’s

Naturals, 14 May 2018, https://beekeepersnaturals.com/blogs/blog/something-rotten-in-honey-industry.

Wells, Jeff. “Growing pains: Why supermarkets are struggling to source local products.” Grocery

Dive, 26 Apr. 2017, https://www.grocerydive.com/news/grocery–grocery-source-local-vegetables-fruit-produce/535172/.

“What is the Food System?” Future of Food, University of Oxford Martin Programme on the

Future of Food, www.futureoffood.ox.ac.uk/what-food-system.