Who Decides What’s for Dinner?

The Skinny on the Freshman 15: College Dining Experience

Cynthia Cahya

I’m one of those people that just looks at a burger and gains weight, so the Freshman 15 was something I was always conscious of and honestly, terrified of. At home, I had been able to manage my weight pretty well because my parents stocked the fridge with fresh, healthy options. Coming to college, you walk into your campus dining hall with every intention to eat a healthy meal but just one look at the salad bar’s limp greens has you opting for a slice of pizza instead. The limited selection of wholesome dining hall fare made it easy for me to put healthy eating aspirations on the back burner. This attitude is representative of the college dining experience for many students. In order to meet the demands of feeding tens of thousands of college kids and remain profitable, campus dining halls are sacrificing fresh and healthier meals for cheaper, processed foods and it is reflecting in the physical well-being of the students.

Freshman 15: Fact or Fiction?

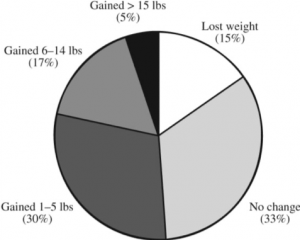

The “Freshman 15”, a reference to the double-digit weight gain after freshman year has become a standard part of college lore, especially among young women. What is college, after all, but access to dining halls with prepaid meal cards, late-night partying or studying fueled by high-calorie snacks from the late-night campus spots, and gossip sessions served up with a side of ice cream. But is the freshman 15 just a “Lochness” monster of campus life – a much reported phenomenon with little documentation behind it? College weight fluctuation is a relatively new field of study. However, studies are already showing a concerning trend. While the legendary Freshman 15

was rare among respondents, the results show that college freshman are gaining an average of 7.4 pounds after their first year (Mihalopoulos, 2008). It should be noted, that this rate of weight gain is nearly 6 times that reported for the general population. If such a rate were sustained for several years, many of the students would become obese. In another study done with freshman from Cornell University, the mean weight gain was 5.29 pounds, a value significantly different from 0. The data indicates that eating in dining halls accounted for 20% of variance in weight gain (Levitsky, 2004). These weight studies clearly demonstrate that significant weight gain during first semester college is a real phenomenon and can be attributed to tangible environmental stimuli. Considering the U.S. adult obesity rate stands at 42.4 percent (Warren, 2020), it is critical that we look at the college dining environment in an effort to reduce or reverse the epidemic of obesity currently observed.

A Closer Look into IU’s Dining Service

To get a better idea of the college dining environment and IU dining, I decided to visit Forest residence hall’s Woodland Eatery, IU’s newest and most extensive dining hall. As I walked around the dining hall it looks closer to a shopping-mall food court, with a dizzying variety and limitless quantity. Soda and other sugary drinks are everywhere, nestled alongside alluring arrays of candy, ice creams, cookies, cakes and pies. When I asked staff if there was a salad bar on site, they said it was closed until further notice pointing to the pre-packaged processed foods as the only ready options available for grab and go as IU dining is only serving takeout or pre-packaged meals due to COVID-19.

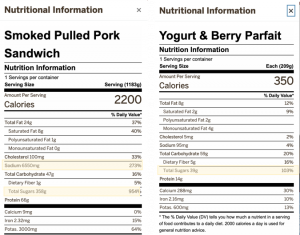

Takeout and prepackaged meals are an understandable adjustment during a pandemic, but they are limiting dining options even further. As I walked around to the various stations, they were offering one or two entrees at most with an accompanying side available. I settled on the micro restaurant Farmers Table, which is described as a “rotating menu of brunch and dinner classics with healthy options” (Dining, 2020). Their menu du jour was a pulled pork sandwich, and when I asked for nutritional facts the staff said they have no menus available in-person, rather everything can be found online on IU Dining’s Net Nutrition. For comparison purposes, I also purchased a yogurt parfait from the Grab-and-Go section as it is home to the more traditionally “healthy” options.

Looking at the nutrition facts of the items I ordered, I was surprised. The single pulled pork sandwich was extremely calorically dense at 2200 calories, already more than the recommended 2000 calories a day. Even more concerning was the total sugars, coming in at 954% of the recommended daily value. While the Yogurt & Berry Parfait was lower in calories, once again the total sugar was already 103% of the recommended daily intake. Seeing how this was a single meal, it is not hard to imagine how students eating 3 meals a day at the dining halls could easily surpass the recommended daily nutritional values. Most concerning to me was the extra steps it took to find the nutritional facts. Had I known about the nutritional values in real-time, I would have steered clear of these items. Nutritional labels have been shown to be an important predictor of dietary selections among college students. In a study done at a Midwestern university, the percentages of users who indicated nearly always and sometimes changing their food choices after reading nutrition labels inside the dining halls were 12% and 80%, respectively (Driskell, 2008). In another study, a greater proportion of nutrition label users selected fruits, vegetables and beans and fewer label users selected fried foods and foods with added sugars (Christoph, 2017). The lack of transparency with the nutritional information across IU dining halls is thus taking students’ ability to make more informed choices regarding their dietary quality.

A Concerning Trend in Availability of Healthy Options

The lack of nutritional labeling cannot fix a lack of healthy options within campus dining halls. In a study aiming to determine the availability of “more healthful” (MH) versus “less healthful” (LH) entrée items in the campus dining hall using the American Heart Association guidelines, researchers found that of the total entrée items available, 15% were more healthful and 85% were least healthful (Leischener, 2018). The lack of MH entrée items (15.0%) and overabundance of LH available entrée items (85.0%) suggests the campus dining environment lacks encouragement of healthy dietary behaviors among college students at this university. These results suggest that the environment may influence students’ purchases and that offering a low percentage of MH entrées may result in even fewer MH purchases. Researchers at Cornell University have extensively studied adolescents’ healthful food purchases at the high school level and have determined a lunch room that makes healthier options convenient increases purchases of those healthier options (Hanks, 2012). If we are to instill healthy habits in these young adults, prioritizing nutritious options at college dining halls where students are away from their families for the first time seems like a good step.

The transition from adolescence to adulthood is an important period for establishing behavioral patterns that affect long-term health – the fundamental concern we look to in reforming health is that most chronic diseases are predominantly lifestyle induced. Today, eating processed foods and fast foods may kill more people prematurely than cigarette smoking (Murray, 2010). Thinking back to the pulled pork sandwich and yogurt parfait, these meals were packed with sugar which is characteristic of processed foods tend to be high in sugar, artificial ingredients, refined carbohydrates, and trans fats. The high glycemic products loaded with sweetening agents, flood the bloodstream with glucose without any beneficial nutrients. The resulting spike in glucose leads to abnormally high amounts of insulin, which will also promote angiogenesis, which fuels the growth of fat cells, increases cellular replication and tumor growth. In addition, the liberal amount of animal protein consumed by most American diets promotes excessive insulin-like growth factor–1 (IGF-1), making a synergistic sandwich of insulin and IGF-1, which may accelerate aging of the brain, interfere with cellular detoxification and repair, and promote cancer (Fuhrman, 2018). The overconsumption of processed food has created a nutritional disaster and a significant health crisis that will not be solved by any government health care reform.

A Profit Driven Model

Given the many findings all pointing to the same trends in college dining experiences, why haven’t campus’s switched to healthier options? Campus dining facilities need to run their operations profitably. Healthy foods are more expensive to produce, giving foodservice operations little incentive to offer different options. Some colleges facing budget cuts or pushback on increased tuition, for example, have opted instead to raise revenue through services such as dining halls. With the rise in contract managed food services, campus dining became a profitable function of higher education with approximately $18.9 billion dollars in profit for the college food service industry, compared to just $1.89 billion in 1972. (Mathewson, 2017). At many schools, the dining hall profits can be significant. Notre Dame, for instance, considers its dining to be “a major contributor of revenue to the university’s academic mission.” In response to an invitation to bid on the contract to operate the dining services at Southeast Missouri State University, the food-service provider Chartwells promised, $6.5 million in facility improvements and nearly $3 million a year in guaranteed commissions, the company offered a $500,000 signing bonus, cheaper food for prospective students visiting the campus, and 14 free meal passes for university employees per semester. Approximately 40% of schools have private companies manage their cafeterias, firms such as Sodexo, Aramark, and Compass group — all of which have to build profit into the prices they charge for food (Dhillon, 2019).

The increasing dependence on campus dining halls as a profitable function and the potential health implications, begs the question of whether we should expect dining halls to carry the financial weight of college institutions. Shouldn’t we want these dining halls to focus on feeding its students as healthily as possible? The particulars of the dining hall contracts reveal that much of the meal plan cost does not go towards an individual’s food. Colleges use dining hall revenue to shore up their balance sheets — renovations to the president’s house, private parties catered for employees, free meals for athletic officials in exchange for free football tickets. These arrangements, which auditors have criticized, can create revenue streams outside the normal budgeting process for funding pet projects, raising the potential of abuse (Saul, 2015). More importantly, what hidden costs are they paying for in an obesogenic food environment, where there is an increased availability, and therefore consumption of, fairly low cost, highly processed foods, unlike anything previously seen in our culture? Sporadic meal patterns and diets lacking nutrient density, including minimal consumption of vegetables, fruit, and dairy products, increase nutritional risk and unwanted weight gain. In fact, Pliner et al., using a 69-question food frequency tool, found that a low intake of vegetables and fruits was the sole dietary predictor of weight gain among college freshman (Pliner, 2015). Although college weight gain may be viewed as small, the associated risks can be significant and have a great impact on their later adult lives.

When food is seen more as a revenue stream for strapped universities than as vehicles for improving health, there are costs that students are paying for in the short and long-term.There’s obviously an element of choice in terms of dining, but it becomes difficult when the choices available are bad or slightly less bad. First-year college students represent a critical group because of the potential for early prevention of eating behavior maladaptation, such as low intake of fruits and vegetables and high intake of processed foods, which can be tracked forth into adulthood and increase the risk of weight gain and other cardiometabolic disorders. The college dining environment does not simply feed college students but has the potential to be highly impactful in the dietary behaviors of college students.

References

Christoph, M. J., & Ellison, B. (2017). A Cross-Sectional Study of the Relationship between

Nutrition Label Use and Food Selection, Servings, and Consumption in a University Dining Setting. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 117(10), 1528–1537. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2017.01.027

Driskell, J. A., Schake, M. C., & Detter, H. A. (2008). Using Nutrition Labeling as a Potential Tool for Changing Eating Habits of University Dining Hall Patrons. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 108(12), 2071-2076. doi:10.1016/j.jada.2008.09.009

Farberman, R. (2020). The State of Obesity 2020: Better Policies for a Healthier America. Retrieved December 01, 2020, from https://www.tfah.org/report-details/state-of-obesity-2020/

Fuhrman J. (2018). The Hidden Dangers of Fast and Processed Food. American journal of

lifestyle medicine, 12(5), 375–381. https://doi.org/10.1177/1559827618766483

Hanks, A. S., Just, D. R., Smith, L. E., & Wansink, B. (2012). Healthy convenience: nudging

students toward healthier choices in the lunchroom. Journal of public health (Oxford, England), 34(3), 370–376. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fds003

IU Dining. (2020). Eateries. Retrieved December 01, 2020, from https://dining.indiana.edu/hours/eateries.html

Leischner, K., McCormack, L. A., Britt, B. C., Heiberger, G., & Kattelmann, K. (2018). The

Healthfulness of Entrées and Students’ Purchases in a University Campus Dining Environment. Healthcare (Basel, Switzerland), 6(2), 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare6020028

Levitsky, D. A., Halbmaier, C. A., & Mrdjenovic, G. (2004). The freshman weight gain: a model

for the study of the epidemic of obesity. International journal of obesity and related metabolic disorders : journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity, 28(11), 1435–1442. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ijo.0802776

Mathewson, T. G. (2017). Here’s Why Food Is So Insanely Expensive at College. Retrieved December 01, 2020, from https://money.com/why-food-college-expensive/

Mihalopoulos, N. L., Auinger, P., & Klein, J. D. (2008). The Freshman 15: is it real?. Journal of

American college health: J of ACH, 56(5), 531–533. https://doi.org/10.3200/JACH.56.5.531-534

Murray CJ, Atkinson C, Bhalla K, et al. ; US Burden of Disease Collaborators. The state

of US health, 1990-2010: burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors. JAMA. 2013;310:591-608. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.13805

Saul, S. (2015, December 06). Meal Plan Costs Tick Upward as Students Pay for More Than

Food. Retrieved December 08, 2020, from https://www.nytimes.com/2015/12/06/us/meal-plan-costs-tick-upward-as-students-pay-for-more-than-food.html