Big Beverage

Ruhan Syed

How Corporations in the Food and Beverage Industry Profit from Indigenous Water Disposession

Introduction

Imagine this, you are on your coffee break at work and find yourself thirsty and wanting a quick snack, you reach into the fridge grab a bottle of Poland Spring water, and a granola bar and go about your day. When we grab those really convenient water bottles and snacks, we often don’t think about the journey of production and where it comes from. While those of us in big cities enjoy and experience the convenience of water and other products being easily available, we often don’t consider how what life near these production plants looks like. For example, in 2018 The Guardian reported from First Nations reserves in Canada detailing numerous health issues such as hepatitis A, scabies, ringworm, and much more (Shimo, 2018). The causes of diseases such as these are most commonly linked to two key issues, lack of water infrastructure or just a plain lack of water. The root cause of this lack of water for First Nations People in Canada was the theft of millions of liters of water a day from indigenous land. Unfortunately, the situation in Canada in 2018 was not the only instance of indigenous populations being hurt by a lack of critical water infrastructure. All over the world indigenous populations have their water stolen from them by food and beverage corporate giants, like Nestle and General Mills, and consumers are often left in the dark.

Who are Indigenous Peoples?

The food and beverage industry is able to get away with water dispossession as there is very little education about who indigenous peoples are. Indigenous people (also known as first peoples, first nations, aboriginal peoples, native peoples, and autochthonous peoples) are ethnically and culturally distinct groups of people who are native to an area later colonized and settled by a later ethnic group. Furthermore, indigenous people have a long and continued tie to the land and ecosystems that they are native to for a multitude of reasons including religion and heritage. These long-lasting ties to the land have existed and weathered centuries due to the continued responsible and sustainable practice (ILO, 1989).

The United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues has reported that there are about 370 million indigenous peoples living across about 70 countries. The reports have also noted that they are often oppressed people who are not afforded the same political and economic rights as the ethnic groups that settled their lands. This includes the exploitation of their lands for profit, desecration of religious and heritage sites, and barriers to political participation (UNPFII, n.d.). Some examples of indigenous people across the world include the Native American tribes, the Maya, Palestinians, Armenians, and dozens if not hundreds of other ethnic groups.

Water Theft in the Food Industry and Its Effects

Water theft or water dispossession from indigenous populations is a simple concept, it is when an indigenous group has their water taken from them without their consent (Hidalgo et al., 2017). This usually occurs when a government and a business come to an agreement to sell the water, as it is their legal right to do so, without consulting the indigenous groups dependent on it and without sharing any of the profit gained from the sale of their water. For the food and beverage industry, this occurs often in Canada by Nestle and in occupied Palestine by General Mills.

Canada

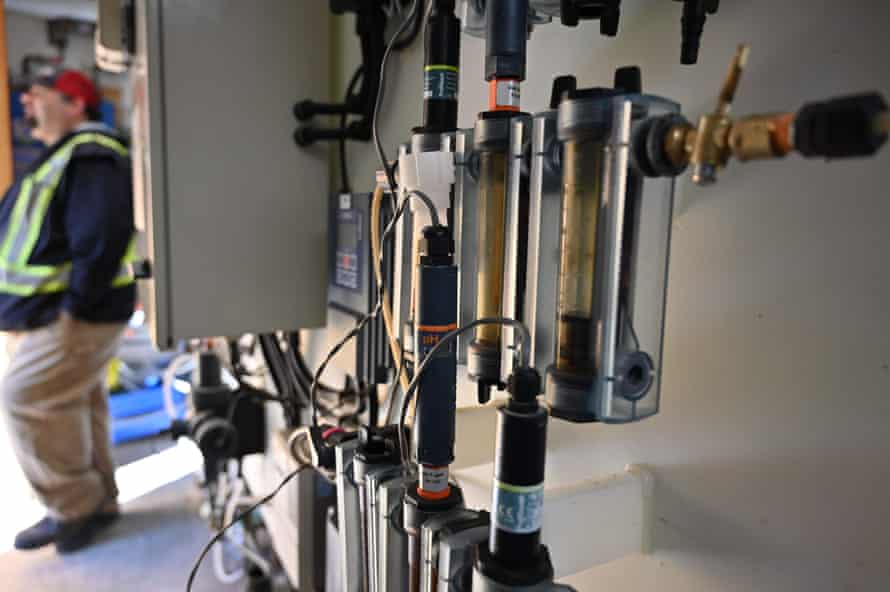

Canada is a country with a relatively low population, and it is home to sixty percent of the world’s lakes and one-fifth of the world’s freshwater supply. This has attracted massive food and beverage companies like Coca-Cola, Pepsi, and Nestle who come in and purchase the land and water rights from the Canadian government and use it for bottled water or other beverages (Shimo, 2018). While the corporations make billions of dollars, and the Canadian government makes millions, Indigenous groups make no money and are only harmed through this disruptive and destructive process. Furthermore, when corporations extract this water, they do not distribute it in a need-based manner and will ship it across the world to wealthier regions as it will make them the most money. This means that Indigenous groups, whose water is being stolen, do not get affordable access to the water being extracted just a few mere miles away from them. Beyond that, due to Indigenous groups being circumvented when beverage corporations purchase water rights and the neglect of provincial and the federal governments in infrastructure development for First Nations reserves, indigenous people are limited to purchasing bottled water or using polluted water from broken down treatment plants and tainted pipelines.

Retaining the right to manage water sources has allowed the Canadian government to sell water rights and cut indigenous peoples out of the process and profits

Nestle has been an especially active company engaging in water dispossession from Canadian First Nations groups. Canada is one of the highest-ranked countries according to the United Nations Human Development Index, yet many of the residents of the Six Nations Reservation in Ontario do not have reliable access to water and plumbing. However, this is a new development, for centuries the Erwin Well has been a reliable, accessible, and safe water source for Indigenous peoples. Ever since Nestle began pumping water on land residents have noted that the water has become polluted, odorous, and unsafe for consumption or use (McIntyre, 2021). This has pushed indigenous peoples in Canada to be reliant on outdated water treatment plants or bottled water companies, like Nestle, for all of their water needs. The First Nations has attempted to rectify this situation and stop Nestle from pumping through legal action. However, the Canadian court system has not been an easy or successful journey for Indigenous groups attempting to regain control of their water. Much of the (legal) frustrations that First Nations groups have faced in attempting to retain their water rights stems from the fact that while First Nations groups do technically own the water, the Canadian government has retained the right to manage the water sources (McIntyre, 2021). Retaining the right to manage water sources has allowed the Canadian government to sell water rights and cut indigenous peoples out of the process and profits, further hindering the development of these communities.

Palestine

In occupied Palestine, Palestinians not only have to live in fear of armed violence in the form of bullets and bombs every day, but they also have to live through the violence of not having control over their own natural resources – especially water. The dispossession of water in Palestine for factories operated by companies such as General Mills has made it increasingly difficult for Palestinians to cultivate native crops and survive off of their own land. The issue of water theft from Palestinians recently entered public discourse across the United States following the decision of the popular ice cream company, Ben and Jerry’s, to no longer operate in some parts of Palestine citing human rights abuses against Palestinians (Ring & Federman, 2021). To better understand the issues that Palestinians face I interviewed a Palestinian-American student activist whose family still owns farmland in Palestine. It is important to note when I reference my conversations with the Student I do not include their name as many Palestinians live in fear of retribution for speaking up.

Similar to Canada, Israel is one of the most developed countries in the world according to the United Nations Human Development Index and this has attracted many major corporations to have regional manufacturing centers(UNHDR, 2020). One of which is General Mills and its subsidiaries such as Pilsbury. However, this highly developed and economically rich experience is far from reality for the Palestinian people (Niehuss, 2005). In our interview, the Student spoke about the key cause of water dispossession in Palestine in manufacturing.

“why waste water on the desert when you have fertile farmland and farmers to worry about?”

When illegal settlements spring up across the West Bank, it is often atop the ruins of bulldozed Palestinian villages (Baum & Perry, 2021). This means that when these General Mills manufacturing centers are being built they divert vast amounts of water in the construction process. After construction, that water diversion continues to occur as the new settlements pump water through miles of pipes to feed the demand of food production factories such as General Mills’ frozen goods factory in the Atarot Industrial Zone (Baum & Perry, 2021). While there is not nearly as much data on water diversion in occupied Palestine as there is for Canadian Reservations, the Student and I discussed in the interview how the diversion of water from aquifers and other water sources makes land arid and difficult to farm in sustainable ways. Furthermore, I was told stories from the Student’s family and friends about olive tree groves and other farmland being burnt down to make space for new construction projects. These stories of disproportionate water use have been backed up by reports from the World Bank, Amnesty International, and the French National Assembly (Amnesty, 2009). However, throughout our whole conversation I was left struck by a specific sentence the Student said to me. After asking them about what was perhaps the most frustrating thing for Palestinians to experience with water diversion they responded with, “Israel often says ‘they made the desert bloom’, but I have always wondered – why waste water on the desert when you have fertile farmland and farmers to worry about?” (Syed, 2021). Much like their counterparts in Canada, Palestinians have attempted to engage in legal rectification to protect their right to water, unfortunately, the Palestinians have also been met with legal roadblocks as they attempt to navigate this increasingly dire situation (Niehuss, 2009). While General Mills is not the only company guilty of operating in occupied Palestine, the heavy use of water in their production process has left Palestinians with little to no access to reliable and affordable water sources.

Next Steps

In our everyday lives, we consume food because it is necessary, but we consume food without considering where it came from. While the saying does go “Ignorance is bliss” that bliss is only experienced by the consumer and it is the indigenous populations of the world who already suffer much in their homelands who pay the true cost. The best way to move forward is to first reduce your individual consumption of bottled water. More often than not, the filtered tap water in your home is the exact same quality as the bottled water brands we purchase. Utilizing reusable water bottles or simply taking a few sips at a water fountain is great for the environment and helps lessen the demand for bottled products. This would push companies like Nestle in Canada to pump less water, protecting indigenous water reserves and the quality of surrounding sources. Second, get civically engaged call your local and national government representatives and ask them to take a better stance on indigenous water rights at home and abroad. You can also support indigenous groups financially through organizations that work on the ground to provide them with better water options. Finally, in a free-market consumer movements have the ability to affect a companies behavior. Therefore, you can show your support for indigenous water rights by limiting or ending the consumption of goods and services from companies engaged in water dispossession.

REFERENCES

Shimo, A. (2018, October 4). While Nestlé extracts millions of litres from their land, residents have no drinking water. The Guardian. Retrieved December 10, 2021, from https://www.theguardian.com/global/2018/oct/04/ontario-six-nations-nestle-running-water.

Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention, 1989, International Labour Convention C. 169 [ILO C.169].

Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues. (n.d.) Indigenous Peoples fact sheet [Fact Sheet]. United Nations. https://www.un.org/esa/socdev/unpfii/documents/5session_factsheet1.pdf

Hidalgo, J. P., Boelens, R., & Vos, J. (2017). De-colonizing water. dispossession, water insecurity, and indigenous claims for resources, authority, and Territory. Water History, 9(1), 67–85. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12685-016-0186-6

McIntyre, G. (2021, April 30). First Nations against Nestle. ArcGIS StoryMaps. Retrieved December 10, 2021, from https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/9f2c0955b33f438995839acb887f7f7b.

Ring, W., & Federman, J. (2021, July 19). Ben & Jerry’s to stop sales in West Bank, east Jerusalem. Associated Press News. Retrieved December 7, 2021, from https://apnews.com/article/ben-and-jerrys-ice-cream-palestinian-territories-d8488b4c9c19dac11e2c253530d63014.

Human development report 2020: UNDP HDR. Human Development Report 2020 | UNDP HDR. (2020). Retrieved December 10, 2021, from https://report.hdr.undp.org/.

Niehuss, Juliette (2005). The Legal Implications of the Israeli-Palestinian Water Crisis. Sustainable Development Law & Policy, Volume 5 (Issue 1)

Troubled Waters– Palestinians Denied Fair Access To Water. AmnestyUSA.org. (2009). Retrieved December 7, 2021, from https://www.amnestyusa.org/files/pdfs/mde150272009en.pdf.

Dalit Baum & Noam Perry. (2021, May 25). We’re boycotting Pillsbury. here’s why you should join us. American Friends Service Committee. Retrieved December 10, 2021, from https://www.afsc.org/blogs/news-and-commentary/were-boycotting-pillsbury.

Syed, R (2021, December) Personal Interview [Phone Interview].