The Depop Dilemma

Angela Apicella

Deep in the trenches of the Great Quarantine of Spring 2020, I decided to do the one thing that I could only do out of sheer boredom: clean my closet. There was an issue of storage space in my room thanks to a combination of my aunt’s old Y2K clothes, my mom’s old 90’s jeans, and the items I had kept from my middle school mall brat days. After a day of sorting clothes in my closet, I realized I had a large amount of clothing that I never wear but were still good quality. I had heard about Depop when I was passing time scrolling endlessly in TikTok. From my understanding of the platform that I gained by watching a few 30-second videos, it was a resale app that had a special market for Y2K and 90’s fashion. Thinking that Depop would be the perfect platform to give my clothes a new home, I created an account and linked my newly created PayPal to it. I realized that I had no idea how to fairly price my secondhand clothing. This confusion on fair pricing was not resolved after looking through Depop; the clothes dramatically ranged in prices despite some items being obviously not worth their prices.

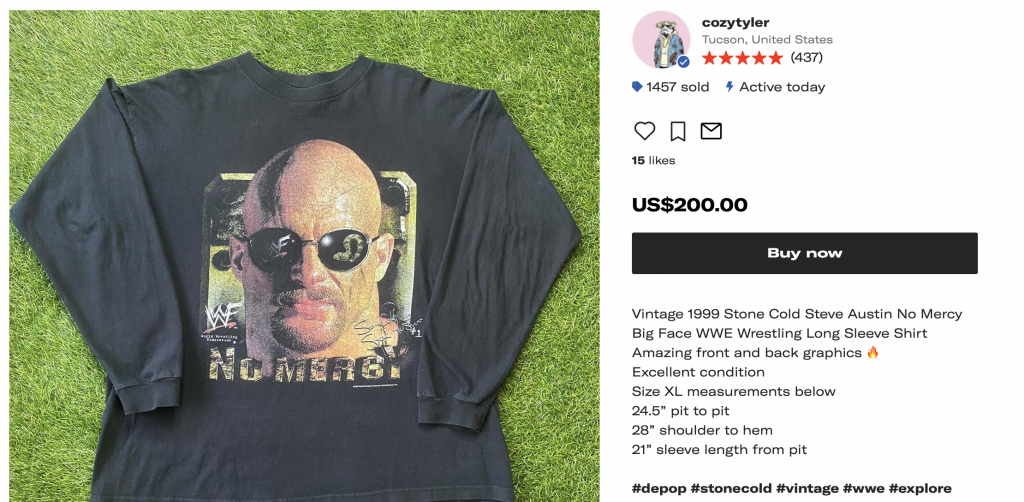

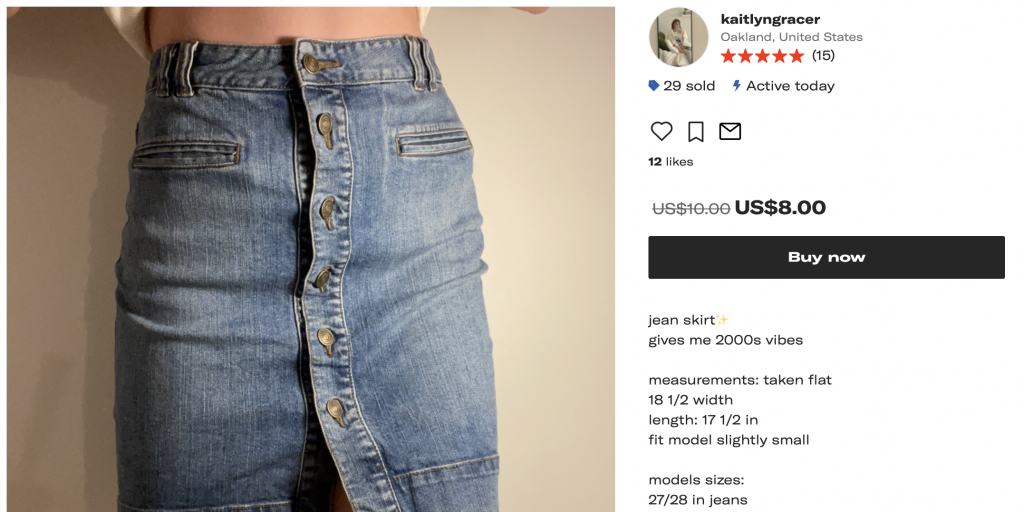

Returning to the app over a year later, I see the same mismatching of prices from a $150 1999 Stone-Cold Steve Austin t-shirt to an $8 jean skirt that “gives me [the seller] 2000s vibes”. User Kaitlyn Rumbuc, a seller of the 2000s vibes jean skirt, offers many women’s clothing items that she thrifted herself at reasonable prices (@kaitlyngracer, 2020). User Cozy Vintage, the seller of the extra-large Stone-Cold Steve Austin t-shirt, has previously owned graphic t-shirts and sweatshirts that are allegedly rare designs (@cozytyler, 2019). Through looking at active users’ profiles, I found that most advertise themselves as sustainable or disclose that their products came from thrift stores. Selling previously owned clothing is an excellent way to get maximum use from items, fights against disposable fast fashion practices, and allows you to make a bit of a profit off your old clothing. While all of this is true for selling your own old clothes, buying clothing from thrift stores for the purpose of reselling on Depop is a problematic practice that causes deceitful pricing and selling, over-consumption, and ultimately gentrification of thrift stores. Although Depop was created to connect smaller creatives to consumers, the app has transformed into a toxic marketplace that upholds thin, White beauty ideals which causes young consumers to buy more clothes from the site to fit the ideals. The platform’s faults coupled with the reseller’s deceitful motivations has caused Depop to become another detrimental by-product of the overconsumption faced in our capitalist society.

The Well-Meaning Origins of Depop

Created in 2011, Depop began as a way for PIG Magazine founder Simon Beckerman to connect his readers directly to the advertised creatives who were featured in the magazine. It was then re-worked to become a hybrid of a social media site and a third-party online seller where users can set prices and sell to other users. This shift was mainly due to the popularity of online platforms in the early 2010s (Lorenz, 2019). According to the website’s mission statement, “Depop is the community-powered fashion ecosystem that’s kinder on the planet and kinder to people,” (Depop, 2021). The U.K.-based company has had a lot of success through making community and sustainability at the forefront of their business, especially with the Generation Z demographic. Pew Research Center defines Generation Z as anyone born between 1997 and 2012, and a main distinguishing feature of this group is their reliance on technology from an early age (Dimock, 2021). Due to the reliance on technology, Generation Z tends to be the main target when it comes to online platforms. According to a 2019 TechCrunch article, about 90% of Depop’s active users are under the age of 26 (Lunden, 2019). Due to Depop’s popularity with the younger Millennial and Generation Z demographic and independent seller model, Etsy acquired the company for $1.625 billion in June 2021 (Heilweil, 2021). While this acquisition reflects Depop’s influence with Generation Z to larger companies, there are some valid criticisms of the platform’s current practices and how they affect the malleable minds of this young market.

Promotion of Thin, White Models

Browsing through the app’s “Explore” page, it is difficult not to notice that many of the featured models tend to be thin and White. This apparent promotion of the thin, White model is an issue that has been addressed by the company in the past. Depop’s Instagram post in June 2020 responded to the Black Lives Matter Movement and their personal pitfalls with diversity with a statement: “Diversity has always been fundamental to Depop- but it hasn’t been fully represented on our platform and we’re changing that,” (Depop, 2020). Although the company addressed their lack of diversity and proposed a commitment to change, over a year later the app is still prioritizing thin, White models. In a 2021 Vice article about Depop fueling body dysmorphia, a Cal Poly undergraduate and Depop seller found that using a thinner model with a tank top she wanted to sell was more successful on the app compared to the same tank top modeled by someone with a slightly larger waist (Smothers, 2021). The app fuels the same problematic ideal that is apparent in the rest of the fashion industry: having a body type that is a trend itself. This problematic trendiness of body types makes the consumer think that buying the promoted clothing will help them reach this standard and will subsequently causes them to keep buying until they reach this standard.

Cal Poly undergraduate and Depop seller found that using a thinner model with a tank top she wanted to sell was more successful on the app compared to the same tank top modeled by someone with a slightly larger waist (Smothers, 2021).Along with causing over-consumption, the promotion of this clothing leads to lower self-esteem for this young, Generation Z audience. The effect of models on young women’s self-esteem has been proven through Marsha L. Richins’ 1991 study in the Journal of Consumer Research. Richins found that young collegiate women who were exposed to models in advertising compared themselves negatively against the model (Richins, 1991). Models on Depop, even though they are advertising secondhand clothing, would also have this effect on the impressionable Generation Z audience. Since these models make young Depop consumers feel bad about themselves, this can cause them to buy more through the coping mechanism of retail therapy (Scott, 2020). Therefore, the negative self-esteem created by the promotion of unattainable beauty standards has the potential to cause over-consumption of secondhand clothes on Depop through the positive psychological effects that happens when buying more goods.

Over-Consumption of Thrifted Goods and the Reseller’s Profit

Besides the beauty ideals causing over-consumption on behalf of the consumers on Depop, over-consumption also occurs on the behalf of the resellers. Due to the trendiness of thrifted goods to Generation Z, resellers on Depop will go to secondhand stores and buy large quantities of items for the sole purpose of reselling them at a higher price on their online store. While the reselling practice allows items to be reused, reselling on Depop does not have ethical intentions behind it. Resellers will over-price their thrifted products since the Generation Z consumer is unlikely to know the difference between genuine vintage and typical thrift store fillers (Nguyen, 2021). This information asymmetry causes the reseller to make a profit no matter what inventory they buy from the thrift store, and thus causes them to buy more products to make more profit. This over-consumption of thrifted goods for the purpose of reselling reflects how the secondhand industry mimics the same consumerism habits that happen in the firsthand fashion industry. According to Jennifer Le Zotte’s 2017 book From Goodwill to Grunge: A History of Secondhand Styles and Alternative Economies, “Thrift-store businesses succeeded because they conformed conventional charity and civic responsibility to the conditions of modern consumerism,” (Le Zotte, 2017, 36). this is perhaps due to the interconnected relationship between the two industries: “Thrift-store businesses succeeded because they conformed conventional charity and civic responsibility to the conditions of modern consumerism,” (Le Zotte, 2017, 36). Although the merchandise might have had a second life, the overconsumption patterns of American consumers reflect the same standards of business seen in the firsthand fashion industry.

While some Depop resellers are attempting to pass off secondhand clothes as vintage, other sellers lie to their customers by selling them fast fashion clothing through the process known as drop shipping (Nguyen, 2021). According to a 2021 Shopify blog: “Dropshipping is an order fulfillment method where a store doesn’t keep the products it sells in stock. Instead, the store purchases the item from a third-party supplier and has it shipped to the consumer. As a result, the supplier doesn’t have to handle the product directly,” (Ferreira, 2021). While this method of selling makes it incredibly easy for the resellers, typically drop shipping is not disclosed or is even falsely sold as a unique or handmade item. Additionally, the drop shipping reseller is typically buying from factories, which may be overseas (Nguyen, 2021). The non-disclosure combined with the young, inexperienced Generation Z consumer causes an unknowing contribution to fast fashion. Under the disguise of Depop, buyers are contributing to the negative environmental and social impacts that come with fast fashion and over-consumption.

Gentrification of Thrift Stores

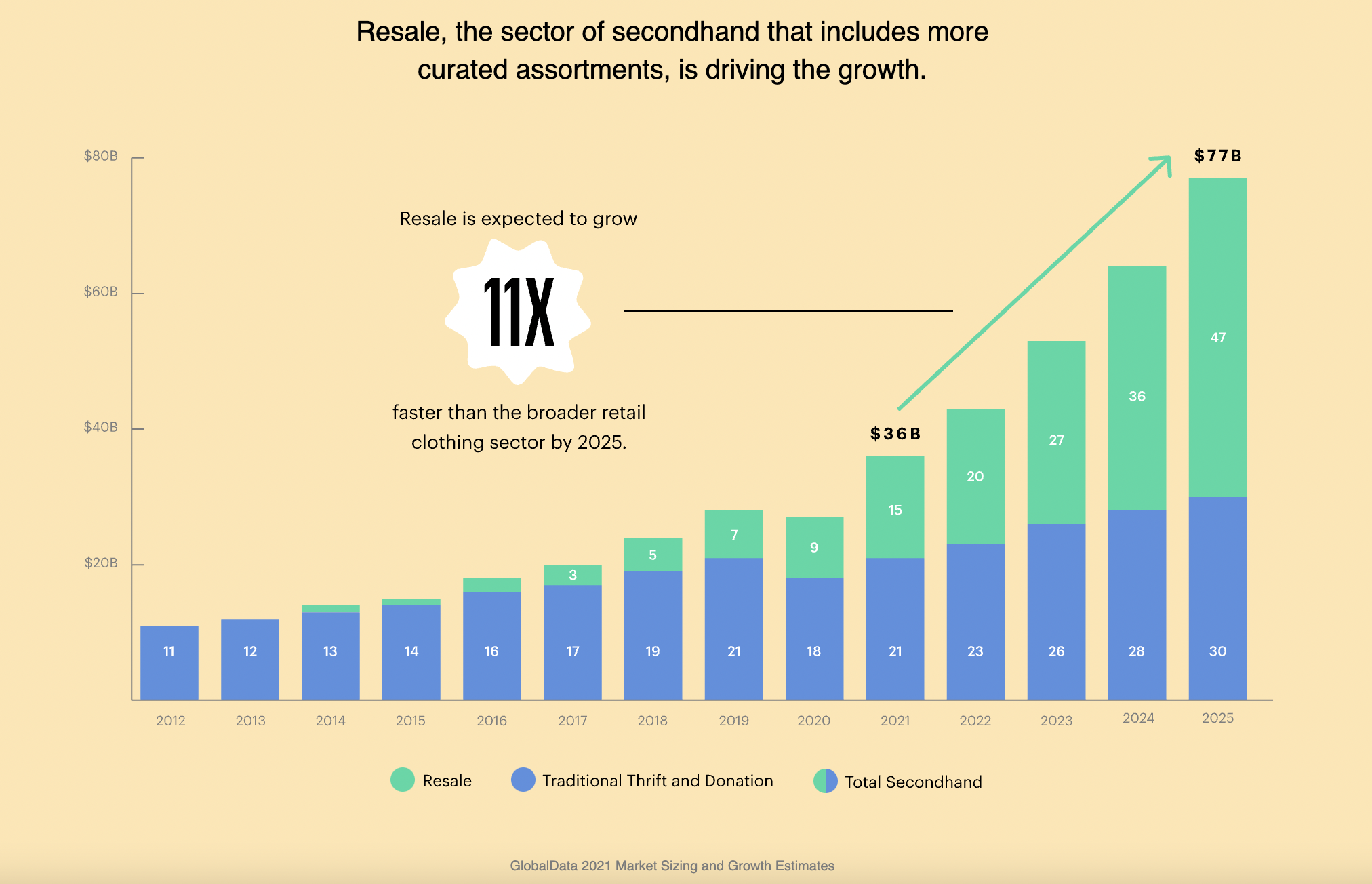

Along with the reseller’s overconsumption from thrift stores causing information asymmetry with a vulnerable buyer, another negative consequence that comes from this business practice is the general raising of thrift store prices. According to the “2020 Resale Report” done by secondhand reseller thredUP, the secondhand apparel market was $28 billion in 2019 and is expected to grow to $77 billion by 2025 (thredUP, 2020). The current success and projected growth of the secondhand market are due to the increased demand for these products by consumers and subsequently resellers. In turn, the increased overall demand causes the prices of the thrifted products to rise. According to a Vox article on Depop sellers, the reseller’s demand for thrifted products is especially harmful since this demand is for products that they do not personally need (Nguyen, 2021). Essentially, resellers are demanding more products than they need and are causing prices to rise as a negative consequence.

The main issue behind thrift stores raising prices on their products is that lower-income people are deterred from stores that were meant to serve affordable clothing. According to a 2020 Refinery29 article on Depop gentrification, working-class people and families are increasingly having to clothe themselves through charities and clothing banks due to the increase of prices in thrift stores (Romano & Rex, 2020). Besides charities and clothing banks, lower-income shoppers may resort to environmentally harmful fast fashion brands to seem well-dressed and trendy at a low price. This exclusion of poor people to well-made used clothing has led to a thriving vintage market that caters to the wealthy. This effect of excluding lower-income people was warned against by apparel industry analyst Elizabeth L. Cline in her 2012 book Overdressed: The Shockingly High Cost of Cheap Fashion: “Vintage clothing, like designer clothing, is in danger of becoming a rich person’s sport, forcing well-made used clothing even further out of the reach of the average consumer,” (Cline, 2012, 133). “Vintage clothing, like designer clothing, is in danger of becoming a rich person’s sport, forcing well-made used clothing even further out of the reach of the average consumer,” (Cline, 2012, 133).It seems as if Cline’s prediction has almost come true, as shopping at thrift stores has become sort of a statement for a wealthier shopper to show their advocacy towards the planet. According to the 2020 Medium article “Depop Gentrification and the Middle-Class Superiority Complex”, shopping at thrift stores has become “a badge of honor amongst sustainability activists,” (Kornelija, 2020). By shopping at thrift stores becoming a demonstrative act of environmental support, it is perceived as though lower-income shoppers are not buying from thrift stores since they do not care about the environment. Resellers’ demands causing a raise in thrift store prices exclude lower-income people who could benefit from these products and are reframing their lack of purchase choice as conscious defiance to sustainability.

If Not Depop, What Should I Do with My Used Clothes?

While our capitalist culture has made us think that we cannot do any task unless it allows us to save or make money, Depop is not the answer to combatting the problems of fast fashion. The best thing that you can do with your used clothes is to give them directly to someone who will use them. Give them to a friend or a family member who is your size, ensuring that your old clothes will have a new life with a trusted person. Attend a clothing swap and walk away with some new clothes of your own. Donate your clothes to a homeless shelter, especially if they are useful weather-proof products like coats or boots. Donate your specific types of clothing to organizations that use that type of clothing for their programming. If you do not find someone to reuse your old clothing and you consider yourself a crafty person, perhaps it is time to think of repurposing your old fabrics. Give your clothes a new life by combining fabrics to make a blanket or a tote. The best thing to ultimately do to avoid the overconsumption of the fashion industry is simply to stop over-consuming. Reducing your consumption by buying better and fewer products is the most sustainable consumption practice that we could do as consumers, and you do not even need to download an app for it.

References

@cozytyler. (2019). ⚡️ cozy VTG ⚡️‘s shop – depop. Depop. https://www.depop.com/cozytyler/.

@cozytyler. (2021, November 22). Vintage 1999 stone cold Steve Austin no mercy big… Depop. https://www.depop.com/products/cozytyler-vintage-1999-stone-cold-steve/.

@kaitlyngracer. (2020). Kaitlyn Rumbuc’s shop. Depop. https://www.depop.com/kaitlyngracer/.

@kaitlyngracer. (2021, November 22). Jean Skirt✨ gives me 2000s vibes measurements:… Depop. https://www.depop.com/products/kaitlyngracer-jean-skirt-gives-me-2000s/.

Barrie, T. (2020, December 24). Depop founder Simon Beckerman’s tips for Success. British GQ. https://www.gq-magazine.co.uk/lifestyle/article/simon-beckerman-depop-tips-for-success.

Clean Air Council. (2019). Clothing Swap. Cleanair.org. https://cleanair.org/greenfest/features/clothing-swap/.

Cline, E.L. (2012) Overdressed: The Shockingly High Cost of Cheap Fashion. Portfolio/ Penguin.

Depop. (2021). About depop: Depop newsroom. About Depop | Depop Newsroom. https://news.depop.com/who-we-are/about/.

Depop [@depop]. (2020, June 15). Depop exists for people pushing for change. It’s a space where style and self-expression thrive naturally. With a community [Picture]. Instagram. https://www.instagram.com/p/CBdp8uTJCi2/

Dimock, M. (2021, May 29). Defining generations: Where millennials end and generation Z begins. Pew Research Center.https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/01/17/where-millennials-end-and-generation-z-begins/.

Ferreira, C. (2021, June 2). What is dropshipping? Shopify. https://www.shopify.com/blog/what-is-dropshipping.

Heilweil, R. (2021, June 2). Why etsy dropped $1.6 billion on Depop. Vox. https://www.vox.com/recode/22465048/depop-etsy-1-6-billion-tiktok-youtube-social-media-gen-z.

Kornelija. (2020, December 10). Depop gentrification and the middle-class superiority complex. Medium. https://medium.com/climate-conscious/depop-gentrification-and-the-middle-class-superiority-complex-a3982c41140b.

Le Zotte, J. (2017). From Goodwill to Grunge: A History of Secondhand Styles and Alternative Economies. The University of North Carolina Press. Chapel Hill, NC.

Lorenz, T. (2019, June 16). Why teens are selling clothes out of their closets. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2019/06/depop-live-selling-clothes-influencers/591595/.

Lunden, I. (2019, June 7). Depop, a social app targeting millennial and gen Z shoppers, bags $62m, passes 13M users. TechCrunch. https://techcrunch.com/2019/06/06/depop-a-social-app-targeting-millennial-and-gen-z-shoppers-bags-62m-passes-13m-users/.

Nguyen, T. (2021, April 26). How thrifting became problematic. Vox. https://www.vox.com/the-goods/22396051/thrift-store-hauls-ethics-depop.

Richins, M.L. (1991). Social Comparison and the Idealized Images of Advertising. The Journal of Consumer Research. (18:1). https://academic.oup.com/jcr/article-abstract/18/1/71/1813828

Romano, K., & Rex, H. (2020, September). Is Depop gentrifying secondhand shopping? The Unethical Side Of Reselling Clothes On Depop. https://www.refinery29.com/en-gb/depop-secondhand-gentrification.

Scott, E. (2020, November 22). Is retail therapy an effective stress reliever? Verywell Mind. https://www.verywellmind.com/retail-therapy-and-stress-3145259#:~:text=%22Retail%20therapy%22%20is%20one%20method,more%20common%20than%20you%20think.

Smothers, H. (2021, April 9). Everyone’s favorite thrifting app favors thin white models. VICE. https://www.vice.com/en/article/n7bje8/depop-thrifting-secondhand-resell-app-favors-thin-white-models.

thredUP. (2020). 2021 fashion resale market and trend report. thredUP. https://www.thredup.com/resale/#transforming-closets.