Excess Clothing: An Environmental Nightmare

Maria Emmanoelides

As a consumer, I can confess that I have a shopping addiction. I’m always looking for the next item that I can add to my ever-growing wardrobe. I’ve come to a dilemma: I’m out of room to store my purchases. My closet physically cannot hold any more hangers and my dresser drawers are so packed that I have to hold the surrounding drawers closed to be able to open the one drawer that I need to get into. None of these issues stop me from purchasing more items. I am persistently receiving emails from my favorite clothing brands about their new inventory and what deals are happening that upcoming week.

I admit that I receive a bit of a rush when I see an abundance of new items every time I look at a brand’s website or walk into their physical store. These feelings of excitement are especially problematic when I go home to visit my family during breaks as a college student. Growing up in Indiana, there isn’t a whole lot of things to do, so whenever I am feeling bored, I would take a trip to my local mall. During each visit to the mall, I find different items in stores, even if the trips are only days apart. Viewing the constant influx of new merchandise caused me to start thinking about the amount of merchandise that is actually sold and where all of the unsold merchandise goes. Products can only be marked down and stay on the sale rack for so long. The consumerist culture that is heavily emphasized in our society has let fast fashion flourish. As a consumer, I always found the abundance of new products to be really helpful, but in reality, the overproduction of clothing within the fashion industry is a major contributor to the amount of waste produced that furthers the environmental destruction of our planet.

The History of Mass Production

Prior to mass production, clothing was handmade and tailored to fit the individual it was being purchased for. With the invention of the sewing machine, there was a gradual growth of clothing production in larger quantities. Throughout the mid-nineteenth century, manufacturers began to produce garments that did not require fitting. Then the department store was introduced, which made a large number of mass-produced goods available for public consumption (Singh, 2017). The growth from the industrial revolution changed the way that the fashion industry operated as a whole. The department stores made these goods available to a variety of consumers which led to manufactures producing more affordable apparel options. Companies began to increase their advertising to attract consumers more frequently. The manufacturers created simpler clothing designs and fabrics to make apparel easier and cheaper to produce (Monet, 2021). The changes made within the fashion industry gave consumers the opportunity to consume as they have never before, and companies capitalized on making more products in order for them to have the opportunity to sell more items and make a greater profit.

Fast Fashion & Overproduction in Our World

Fast fashion has become a huge reason why consumers feel the need to continue to fill their closets with new items. Fast fashion is a term that identifies retailers that put large amounts of clothing into the market based on keeping up with short fashion trends, by using cheap materials. The items are cheap which causes individuals to further their spending because they don’t see the problem because they are focused on the money that they are supposedly saving. The problem stems from the emphasis on the consumerist culture, where individuals are drawn to purchasing items because of the feelings that they elicit due to their purchases. Individuals want to continue having these feelings, so they continue to purchase new items. The cheapness of the clothing draws individuals in and makes the clothing easy to buy. Retailers have increased the amount of buying seasons, which originally ran based on the 4 seasons. Now retailers have new items coming in every week. The influx of merchandise has caused consumers to come to the stores more frequently to see what’s new. The increase in online shopping has created ease for consumers and they have the new inventory of these retailers right at their fingertips.

Having an abundance of choices initially seems like it would be beneficial for the fashion industry. Everyone can find something they want, whenever they want. The excess of what is wanted is where the problem truly lies. Overproduction is the excess of supply over demand (Andriiuk, 2020). There are more items produced than the actual demand of the item. The excess inventory has to go somewhere. Many brands discard the unwanted goods themselves and throw them away or send them to be incinerated. For example, the British luxury brand Burberry faced a considerable amount of backlash when the brand had stated that they had burned about $37 million worth of unsold clothing (Davis, 2019).For example, the British luxury brand Burberry faced a considerable amount of backlash when the brand had stated that it had burned about $37 million worth of unsold clothing (Davis, 2019). Burning merchandise is a practice is used among companies to maintain the value of the brand and its exclusivity.

To get a closer look at the industry, I visited my local mall to speak with some employees of retail stores to look at how their store manages the life of their products. I walked into Express, an American fashion retailer that targets young men and women between the ages of 20 and 30. I asked one of the employees working at the register if I could ask her some questions about how they handle their inventory. The employee stated that they get new shipments of inventory almost every single day and that the inventory stays on the racks for a maximum of 3 months before it is marked down to clearance. I continued to ask questions about what the process was for clothing that wasn’t sold, and she stated that it sometimes goes to outlet stores or distribution centers. She said that she had previously tried to have a conversation with her boss about where the discarded inventory went, but her boss wasn’t aware as well. Like many other brands, the life of the unsold inventory is kept in the dark and the process of discarding it is not discussed.

I then made my way to the Target that is attached to the local mall. The Target Corporation is an American retail corporation that has a wide selection of products including apparel, home furnishings, produce, and electronics. I began speaking with one of the managers at the front end of the store and asked about their processes regarding how they handle unsold apparel merchandise. She stated that the store likes to keep merchandise on the racks for the season and once the season ends, they are placed on clearance and sale racks. I then asked her how often they received new merchandise and she replied saying that they receive new items on a weekly store-wide basis since the store carries women’s, men’s, and kid’s apparel. She then went on to say that a good portion of the clothes is discarded and that these items are automatically thrown into the trash. Discarding these items into the trash is very wasteful and is surprising because there seem to be other options to get rid of unwanted merchandise that gives these items a bit more time of shelf life.

where does it all go?

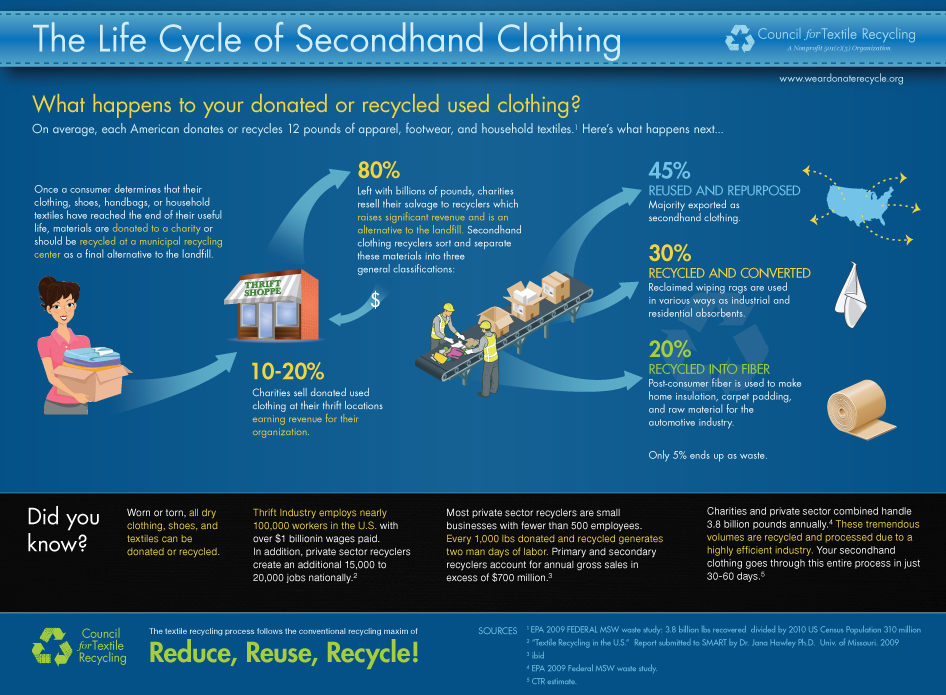

As a society, we have currently been under the impression that donating clothes is a sustainable option for discarding clothes. It is seen as doing a good deed for the community and that you are helping someone who is in need. The amount of clothes that are discarded immensely surpasses the number of people in need. The Council for Textile Recycling is a 501 (c)(3) nonprofit organization trying to raise public awareness about the need to reduce textile waste and the importance of textile recycling. According to the Council for Textile Recycling, only 10-20% of the clothing that is donated to charities is sold at their thrift locations and leaves 80% of the donated clothing to be sold to salvage recyclers. 45% of the clothing is reused and repurposed by being exported as secondhand clothing, 30% is recycled and converted into wiping rags for industrial and residential absorbents, and 20% are recycled into fiber for items that make home insulation, carpet padding, and raw material for the automotive industry (Council for Textile Recycling, 2021). This information suggests that half of the items that are donated are recycled into new materials that don’t go back into the fashion industry. The more interesting question is what happens to the 45% of donated clothing that is sent to be secondhand clothing overseas.

The United States is the largest exporter of used clothing (Shahbandeh, 2021). Many of the donations of used clothing are exported and are then sold to buyers in countries with developing economies. There are street markets where secondhand clothes are sold. These countries also have a large portion of unwanted secondhand goods that aren’t sold at these markets. These items are often taken to pieces of land near the markets and the clothes are burned in order to make room for the incoming clothes. The heavy usage of imported secondhand clothing has caused problems for these countries to have their own textile industries. For example, in Ghana the textile and clothing employment fell by 80% between 1975 and 2000 (Rodgers, 2015). Many African countries are looking to ban secondhand clothes, bags, and shoes to promote their own regions’ textile and leather industries.

Many clothing retailers will give consumers coupons to save money on purchasing new items if they donate old ones as an incentive to keep purchasing from their stores. They often mislead consumers into thinking that their textile garments will be recycled into new garments. Sorting textiles into different materials is very slow, labor-intensive, and requires a skilled workforce. Unfortunately, recycling old clothes into new ones weakens the material. A lot of the garments that are currently made are made of materials that have been mixed together and are hard to separate. According to H&M’s 2016 sustainability report, only .7 percent of the material used in new clothing has been recycled (H&M, 2016). This information is very interesting because H&M is one of the fast fashion companies that use recycling clothing as an incentive. This incentive is very deceptive to the consumers. Even if the clothing is recycled, the lifetime of the item has suffered because the quality has decreased.

Most of our clothing eventually ends up in landfills even after we think that we have disposed of it in better ways. Thinking that our clothes are going to waste is hard to think about because we often think that we are doing a good thing by donating items, but there is just too much that is donated, and it can’t be used. The clothing that goes to the landfill ends up with all of our other trash like your leftover pizza. The difference between your leftovers and your clothes is how they decompose. On average each person discards 70 pounds of textile waste per year, which is about 100 garments (SMART,2021). These items do not just instantly decompose, it would take hundreds of years. But as these textiles sit in these landfills, they release greenhouse gases that pollute the environment. These items don’t just contribute to pollution when they are decomposing, they are also hurting the environment as they are being made. According to Levi’s, making one pair of jeans takes 400 megajoules of energy, 920 gallons, of water, and released 32 kilograms of carbon dioxide (Levi Strauss & Co., 2015). Although companies are working to find ways to recycle materials the technology is just not there yet.

Where do we Go from here?

Consumers are accustomed to overproduction and it seems as though it is not going away anytime soon. There are innovators that are attempting to eliminate pollution and wastefulness in the fashion industry by looking into making biodegradable textiles. These innovators are making biodegradable textile by using live organisms to grow them, which creates environmentally friendly materials in a laboratory. A lot of the garments produced today are woven from plastic-based acrylic, nylon, or polyester threads, and cut and sewn in factories. These materials are chemically produced and are not biodegradable. Many think that the future of fashion could be made from living bacteria, algae, yeast, animal cells, or fungi (Cirino, 2018). Using methods with biodegradable materials could eliminate the need to discard extra waste. Bioengineering could also address problems with the dyes used in textiles. Textile dying uses many human-made chemicals that lead and petroleum-based substances (Cirino, 2018). Using human-made chemicals is really hazardous for humans and the environment. Dye factories also have wastewater, and it is often dumped without any treatment. Using biodegradable fabrics will help ease overproduction and help eliminate textile waste within the fashion industry.

In order for the problem to get better, we need to stray away from fast fashion and focus more on purchasing items that are going to be worn for a longer period of time. It’s important that in order to move away from fast fashion, we must educate consumers about the problems caused by overproduction. The overproduction of clothing enables unsustainable practices, like discarding unused items into the trash, to continue. The only way to actually make change is to decrease the amount of clothing that is being put onto the market. There needs to be a shift in the mindset of the entire society that goes away from consumerist culture and that focuses on possible solutions to minimize waste in our over-consuming society.

REFERENCES

Andriiuk, A. (2020, August 26). How Not to Go Extinct: Overproduction vs Slow Fashion. Sustainability Club. Retrieved December 9, 2021, from https://www.thesustainabilityclub.com/post/how-not-to-go-extinct-overproduction-vs-slow-fashion.

Cirino, E. (2018, September 14). The environment’s new clothes: Biodegradable textiles grown from live organisms. Scientific American. Retrieved December 9, 2021, from https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/the-environments-new-clothes-biodegradable-textiles-grown-from-live-organisms/.

Council for Textile Recycling. (2021). The Life Cycle of Secondhand Clothing. Council for Textile Recycling. Retrieved December 9, 2021, from http://www.weardonaterecycle.org/about/issue.html.

Davis, E. (2019, August 19). Here’s What Really Happens to the Stuff Stores Don’t Sell. StyleDemocracy. Retrieved December 9, 2021, from https://www.styledemocracy.com/what-stores-dont-sell/.

H&M Group. (2016). The H&M Group Sustainability Report 2016. Retrieved December 9, 2021, from https://hmgroup.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/HM_group_SustainabilityReport_2016_FullReport_en.pdf.

Levi Strauss & Co. (2015). The Life Cycle of a Levi’s 501 Jean. Levi Strauss & Co. Retrieved December 9, 2021, from https://www.levistrauss.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/Full-LCA-Results-Deck-FINAL.pdf.

Monet, D. (2014, February 24). Ready-to-Wear: A Short History of the Garment Industry. Bellatory. Retrieved December 9, 2021, from https://bellatory.com/fashion-industry/Ready-to-Wear-A-Short-History-of-the-Garment-Industry.

Shahbandeh, M. (2021, August 5). Used Clothing Leading Exporters Worldwide 2019. Statista. Retrieved December 9, 2021, from https://www.statista.com/statistics/523673/used-clothing-leading-exporters-worldwide/.

Singh, N. (2017, September 25). Fashion history : Mass Market. Medium. Retrieved December 9, 2021, from https://medium.com/@namanpalsingh/fashion-history-mass-market-4698bea668b5.

SMART. (2021). Who is Smart? . Secondary Materials & Recycled Textiles. Retrieved December 9, 2021, from https://www.smartasn.org/SMARTASN/assets/File/resources/SMART_PressKitOnline.pdf.