7.2 Product Life Cycle (PLC)

Why the Product Life Cycle (PLC)?

Once a product is created and introduced in the marketplace, the offering must be managed effectively for the customer to receive value from it. Only if this is done will the product’s producer achieve its profit objectives and be able to sustain the offering in the marketplace. The process involves making many complex decisions. Companies also need expertise to successfully launch products in foreign markets. Given many possible constraints in international markets, companies might initially introduce a product in limited areas abroad. Other organizations, such as Coca-Cola, decide to compete in markets worldwide1.

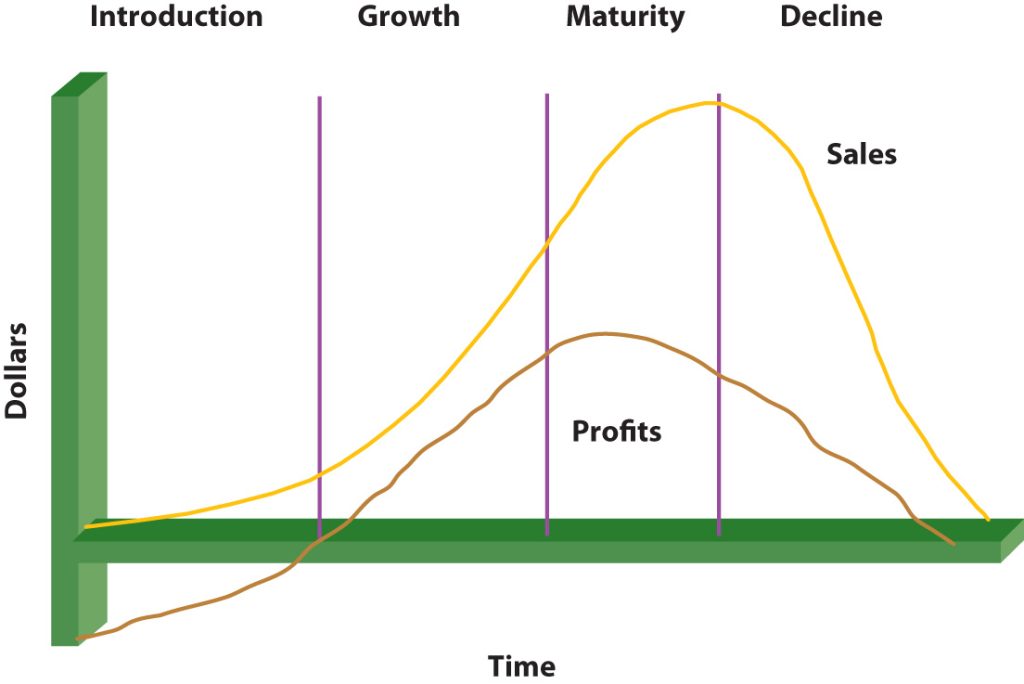

The product life cycle (PLC) includes the stages a product goes through after development, from introduction to the end of the product. Just as children go through different phases in life (toddler, elementary school, adolescent, young adult, and so on), products and services also age and go through different stages. The PLC is a beneficial tool that helps marketers manage the stages of a product’s acceptance and success in the marketplace, beginning with the product’s introduction, its growth in market share, maturity, and possible decline in market share. Other tools such as the Boston Consulting Group matrix and the General Electric approach may also be used to manage and make decisions about what to do with products. For example, when a market is no longer growing but the product is doing well (cash cow in the BCG approach), the company may decide to use the money from the cash cow to invest in other products they have rather than continuing to invest in the product in a no-growth market.

The product life cycle can vary for different products and different product categories. Figure 7.2 “Life Cycle” illustrates an example of the product life cycle, showing how a product can move through four stages. However, not all products go through all stages and the length of a stage varies. For example, some products never experience market share growth and are withdrawn from the market. Generally, as Figure 7.2 illustrates, sales for an industry start at zero during the introduction stage and steadily increase through the growth stage until the end of the maturity stage. Profits typically have the same shape but start in the negative during the introduction stage, cross over into positive during the growth stage and stay there during maturity and even the decline stage, even though sales have dropped dramatically at that point.

Typically the Product Life Cycle pertains to the product, or category, within the industry. It is not company or brand specific. However, there are times that it is applied to individual products within a company, as described below. Most situations though, cause for an analysis of where the industry is and what is likely to occur in the near future.

Figure 7.2: Life Cycle

Diet Coke changed its can to keep from getting outdated.

Wikimedia Commons – public domain.

Other products stay in one stage longer than others. For example, in 1992, PepsiCo introduced a product called Clear Pepsi, which went from introduction to decline very rapidly. By contrast, Diet Coke entered the growth market soon after its introduction in the early 1980s and then entered (and remains in) the mature stage of the product life cycle. New computer products and software and video games often have limited life cycles, whereas product categories such as diamonds and durable goods (kitchen appliances) generally have longer life cycles. How a product is promoted, priced, distributed, or modified can also vary throughout its life cycle. Let’s now look at the various product life cycle stages and what characterizes each.

Stages of the Product Life Cycle (PLC)

The Introduction Stage

The first stage in a product’s life cycle is the introduction stage. The introduction stage is the same as commercialization/product launch, or the last stage of the new product development process. Marketing costs are typically higher in this stage than in other stages. As an analogy, think about the amount of fuel a plane needs for takeoff relative to the amount it needs while in the air. Just as an airplane needs more fuel for takeoff, a new product or service needs more funds for introduction into the marketplace. Communication (promotion) is needed to generate awareness of the product and persuade consumers to try it, and placement alternatives and supply chains are needed to deliver the product to the customers. Profits are often low in the introductory stage due to the research and development costs and the marketing costs necessary to launch the product.

The length of the introductory stage varies for different products. However, by law in the United States, a company is only allowed to use the label “new” on a product’s package for six months. An organization’s objectives during the introductory stage often involve educating potential customers about its value and benefits, creating awareness, and getting potential customers to try the product or service. Getting products and services, particularly multinational brands, accepted in foreign markets can take even longer. Consequently, companies introducing products and services abroad generally must have the financial resources to make a long-term (longer than one year) commitment to their success.

The specific promotional strategies a company uses to launch a product vary depending on the type of product and the number of competitors it faces in the market. Firms that manufacture products such as cereals, snacks, toothpastes, soap, and shampoos often use mass marketing techniques such as television commercials and Internet campaigns and promotional programs such as coupons and sampling to reach consumers. To reach wholesalers and retailers such as Walmart, Target, and grocery stores, firms utilize personal selling. Many firms promote to customers, retailers, and wholesalers. Sometimes other, more targeted advertising strategies are employed, such as billboards and transit signs (signs on buses, taxis, subways, and so on). For more technical or expensive products such as computers or plasma televisions, many firms utilize professional selling, informational promotions, and in-store demonstrations so consumers can see how the products work.

Many new convenient snack packages, such as jelly snacks and packages of different sizes, are available in China and the United States.

Paul Townsend – Old Fashioned Candy – CC BY-NC 2.0.

During introduction, an organization must have enough distribution outlets (places where the product is sold or the service is available) to get the product or service to the customers. The product quantities must also be available to meet demand. For example, IBM’s ThinkPad was a big hit when it was first introduced, but the demand for it was so great that IBM wasn’t able to produce enough of the product. Cooperation from a company’s supply chain members—its manufacturers, wholesalers, and so forth—helps ensure that supply meets demand and that value is added throughout the process.

When you were growing up, you may remember eating Rice Krispies Treats cereal, a very popular product. The product was so popular that Kellogg’s could not keep up with initial demand and placed ads to consumers apologizing for the problem. When demand is higher than supply, the door opens for competitors to enter the market, which is what happened when the microwave was introduced. Most people own a microwave, and prices have dropped significantly since Amana introduced the first microwave at a price of almost $500. As consumers in the United States initially saw and heard about the product, sales increased from forty thousand units to over a million units in only a few years. Sales in Japan increased even more rapidly due to a lower price. As a result of the high demand in both countries, many competitors entered the market and prices dropped2.

Product pricing strategies in the introductory stage can vary depending on the type of product, competing products, the extra value the product provides consumers versus existing offerings, and the costs of developing and producing the product. Organizations want consumers to perceive that a new offering is better or more desirable than existing products. Two strategies that are widely used in the introductory stage are penetration pricing and skimming. A penetration pricing strategy involves using a low initial price to encourage many customers to try a product. The organization hopes to sell a high volume in order to generate substantial revenues. New varieties of cereals, fragrances of shampoo, scents of detergents, and snack foods are often introduced at low initial prices. Seldom does a company utilize a high price strategy with a product such as this. The low initial price of the product is often combined with advertising, coupons, samples, or other special incentives to increase awareness of the product and get consumers to try it.

A company uses a skimming pricing strategy, which involves setting a high initial price for a product, to more quickly recoup the investment related to its development and marketing. The skimming strategy attracts the top, or high end, of the market. Generally this market consists of customers who are not as price sensitive or who are early adopters of products. Firms that produce electronic products such as DVRs, plasma televisions, and digital cameras set their prices high in the introductory stage. However, the high price must be consistent with the nature of the product as well as the other marketing strategies being used to promote it. For example, engaging in more personal selling to customers, running ads targeting specific groups of customers, and placing the product in a limited number of distribution outlets are likely to be strategies firms use in conjunction with a skimming approach.

The Growth Stage

If a product is accepted by the marketplace, it enters the growth stage of the product life cycle. The growth stage is characterized by increasing sales, more competitors, and higher profits. Unfortunately for the firm, the growth stage attracts competitors who enter the market very quickly. For example, when Diet Coke experienced great success, Pepsi soon entered with Diet Pepsi. You’ll notice that both Coca-Cola and Pepsi have similar competitive offerings in the beverage industry, including their own brands of bottled water, juice, and sports drinks. As additional customers begin to buy the product, manufacturers must ensure that the product remains available to customers or run the risk of them buying competitors’ offerings. For example, the producers of video game systems such as Nintendo’s Wii could not keep up with consumer demand when the product was first launched. Consequently, some consumers purchased competing game systems such as Microsoft’s Xbox.

Demand for the Nintendo Wii increased sharply after the product’s introduction.

Link576 – Nintendo Wii (Original Box Design) – CC BY-SA 2.0.

A company sometimes increases its promotional spending on a product during its growth stage. However, instead of encouraging consumers to try the product, the promotions often focus on the specific benefits the product offers and its value relative to competitive offerings. In other words, although the company must still inform and educate customers, it must counter the competition. Emphasizing the advantages of the product’s brand name can help a company maintain its sales in the face of competition. Although different organizations produce personal computers, a highly recognized brand such as IBM strengthens a firm’s advantage when competitors enter the market. New offerings that utilize the same successful brand name as a company’s already existing offerings, which is what Black & Decker does with some of its products, can give a company a competitive advantage. Companies typically begin to make a profit during the growth stage because more units are being sold and more revenue is generated.

The number of distribution outlets (stores and dealers) utilized to sell the product can also increase during the growth stage as a company tries to reach as much of the marketplace as possible. Expanding a product’s distribution and increasing its production to ensure its availability at different outlets usually results in a product’s costs remaining high during the growth stage. The price of the product itself typically remains at about the same level during the growth stage, although some companies reduce their prices slightly to attract additional buyers and meet the competitors’ prices. Companies hope by increasing their sales, they also improve their profits.

The Maturity Stage

After many competitors enter the market and the number of potential new customers declines, the sales of a product typically begin to level off. This indicates that a product has entered the maturity stage of its life cycle. Most consumer products are in the mature stage of their life cycle; their buyers are repeat purchasers versus new customers. Intense competition causes profits to fall. The maturity stage typically lasts longer than other stages. Quaker Oats and Ivory Soap are products in the maturity stage—they have been on the market for over one hundred years.

Given the competitive environment in the maturity stage, many products are promoted heavily to consumers by stronger competitors. The strategies used to promote the products often focus on value and benefits that give the offering a competitive advantage. The promotions aimed at a company’s distributors may also increase during the mature stage. Companies may decrease the price of mature products to counter the competition. However, they must be careful not to get into “price wars” with their competitors and destroy all the profit potential of their markets, threatening a firm’s survival.

Companies are challenged to develop strategies to extend the maturity stage of their products so they remain competitive. Many firms do so by modifying their target markets, their offerings, or their marketing strategies. Next, we look at each of these strategies.

Modifying the target market helps a company attract different customers by seeking new users, going after different market segments, or finding new uses for a product in order to attract additional customers. Financial institutions and automobile dealers realized that women have increased buying power and now market to them. With the growth in the number of online shoppers, more organizations sell their products and services through the Internet. Entering new markets provides companies an opportunity to extend the product life cycles of their different offerings.

IvanWalsh.com – McCafe McDonalds Chinese Shopping Mall – CC BY 2.0.

Many companies enter different geographic markets or international markets as a strategy to get new users. A product that might be in the mature stage in one country might be in the introductory stage in another market. For example, when the U.S. market became saturated, McDonald’s began opening restaurants in foreign markets. Cell phones were very popular in Asia before they were introduced in the United States. Many cell phones in Asia are being used to scan coupons and to charge purchases. However, the market in the United States might not be ready for that type of technology.

Modifying the product, such as changing its packaging, size, flavors, colors, or quality can also extend the product’s maturity stage. The 100 Calorie Packs created by Nabisco provide an example of how a company changed the packaging and size to provide convenience and one-hundred-calorie portions for consumers. While the sales of many packaged foods fell, the sales of the 100 Calorie Packs increased to over $200 million, prompting Nabisco to repackage more products (Hunter, 2008). Kraft Foods extended the mature stage of different crackers such as Wheat Thins and Triscuits by creating different flavors. Although not popular with consumers, many companies downsize (or decrease) the package sizes of their products or the amount of the product in the packages to save money and keep prices from rising too much.

Car manufacturers modify their vehicles slightly each year to offer new styles and new safety features. Every three to five years, automobile manufacturers do more extensive modifications. Some companies, such as Lincoln, change the name of their models to reflect a ‘refresh’ in their branding. Changing the package or adding variations or features are common ways to extend the mature stage of the life cycle. Pepsi recently changed the design and packaging of its soft drinks and Tropicana juice products. However, consumers thought the new juice package looked like a less expensive brand, which made the quality of the product look poorer. As a result, Pepsi resumed the use of the original Tropicana carton. Pepsi’s redesigned soda cans also received negative consumer reviews.

When introducing products to international markets, firms must decide if the product can be standardized (kept the same) or how much, if any, adaptation, or changing, of the product to meet the needs of the local culture is necessary. Although it is much less expensive to standardize products and promotional strategies, cultural and environmental differences usually require some adaptation. Product colors and packages as well as product names must often be changed because of cultural and legal differences. For example, in many Asian and European countries, Coca-Cola’s diet drinks are called “light,” not diet, due to legal restrictions on how the word diet can be used. GE makes smaller appliances such as washers and dryers for the Japanese market because houses tend to be smaller and don’t have the room for larger models. Hyundai Motor Company had to improve the quality of its automobiles in order to compete in the U.S. market. Companies must also examine the external environment in foreign markets since the regulations, competition, and economic conditions vary as well as the cultures.

In Europe, diet drinks are called “light,” not diet. This Coca-Cola product is available in Germany.

Wikimedia Commons – Botella de Coca Cola – CC BY-SA 3.0.

Some companies modify the marketing strategy for one or more marketing variables of their products. For example, many coffee shops and fast-food restaurants such as McDonald’s now offer specialty coffee that competes with Starbucks. As a result, Starbucks’ managers decided it was time to change the company’s strategy. Over the years, Starbucks had added lunch offerings and moved away from grinding coffee in the stores to provide faster service for its customers. However, customers missed the coffee shop atmosphere and the aroma of freshly brewed coffee and didn’t like the smell of all the lunch items.

As a result of falling market share, Starbucks’ former CEO and founder Howard Schultz returned to the company. Schultz hired consultants to determine how to modify the firm’s offering and extend the maturity stage of their life cycle. Subsequently, Starbucks changed the atmosphere of many of its stores back to that of traditional coffee shops, modified its lunch offerings in many stores, and resumed grinding coffee in stores to provide the aroma customers missed. The company also modified some of its offerings to provide health-conscious consumers lower-calorie alternatives (Horovitz, 2008). After the U.S. economy weakened in 2009, Starbucks announced it would begin selling instant coffee for about a dollar a cup to appeal to customers who were struggling financially but still wanted a special cup of coffee. The firm also changed its communication with customers by utilizing more interactive media such as blogs.

Whereas Starbucks might have overexpanded, McDonald’s plans to add fourteen thousand coffee bars to selected stores3. In addition to the coffee bars, many McDonald’s stores are remodeling their interiors to feature flat screen televisions, recessed lighting, and wireless Internet access. Other McDonald’s restaurants kept their original design, which customers still like.

The Decline Stage

When sales decrease and continue to drop to lower levels, the product has entered the decline stage of the product life cycle. In the decline stage, changes in consumer preferences, technological advances, and alternatives that satisfy the same need can lead to a decrease in demand for a product. How many of your fellow students do you think have used a typewriter, adding machine, or slide rule? Computers replaced the typewriter and calculators replaced adding machines and the slide rule. Ask your parents about eight-track tapes, which were popular before cassette tapes, which were popular before CDs, which were popular before MP3 players, Internet radio and other streaming services. Some products decline slowly. Others go through a rapid level of decline. Many fads and fashions for young people tend to have very short life cycles and go “out of style” very quickly. (If you’ve ever asked your parents to borrow clothes from the 1990s, you may be amused at how much the styles have changed.) Similarly, many students don’t have landline phones or VCR players and cannot believe that people still use the “outdated” devices. Some outdated devices, like payphones, disappear almost completely as they become obsolete.

Technical products such as digital cameras, cell phones, and video games that appeal to young people often have limited life cycles. Companies must decide what strategies to take when their products enter the decline stage. To save money, some companies try to reduce their promotional expenditures on these products and the number of distribution outlets in which they are sold. They might implement price cuts to get customers to buy the product. Harvesting the product entails gradually reducing all costs spent on it, including investments made in the product and marketing costs. By reducing these costs, the company hopes that the profits from the product will increase until their inventory runs out. Another option for the company is divesting (dropping or deleting) the product from its offerings. The company might choose to sell the brand to another firm or simply reduce the price drastically in order to get rid of all remaining inventory. If a company decides to keep the product, it may lose money or make money if competitors drop out. Many companies decide the best strategy is to modify the product in the maturity stage to avoid entering the decline stage.

You Try It!