7.1 Product Classifications

Defining the Product

In essence, the term “product” refers to anything offered by a firm to provide customer value, be it tangible or intangible. It can be a single product, a combination of products, a product-service combination, or several related products and services. It normally has at least a generic name (e.g., banana) and usually a brand name (e.g., Chiquita). Although a product is normally defined from the perspective of the manufacturer, it is also important to note two other points-of-view, those of the consumer and of other relevant publics. For a manufacturer like Kraft Foods, their macaroni and cheese dinner reflects a food product containing certain ingredients packaged, distributed, priced, and promoted in a unique manner, and requiring a certain return on their investment. For the consumer, the product is a somewhat nutritious food item that it is quick and easy to prepare and is readily consumed by the family, especially kids. For a particular public, such as the US Food and Drug Administration, this product reflects a set of ingredients that must meet particular minimum standards in terms of food quality, storage, and distribution.

Making this distinction is important in that all three perspectives must be understood and satisfied if any product will survive and succeed. Furthermore, this sensitivity to the needs of all three is the marketing concept in action. For example, a company might design a weight-reduction pill that not only is extremely profitable but also has a wide acceptance by the consumer. Unfortunately, it cannot meet the medical standards established by the US Federal government. Likewise, Bird’s Eye Food might improve the overall quality of their frozen vegetables and yet not improve the consumers’ tendency to buy that particular brand simply because these improvements were not perceived as either important or noticeable by the consumer. Therefore, an appraisal of a company’s product is always contingent upon the needs and wants of the marketer, the consumer, and the relevant publics. We define product as follows: anything, either tangible or intangible, offered by the firm; as a solution to the needs and wants of the consumer; is profitable or potentially profitable; and meets the requirements of the various publics governing or influencing society.

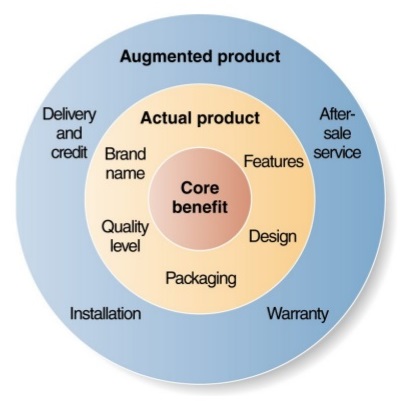

There are four levels of a product: core, actual, augmented, and promised (see Exhibit 7.1a). We begin with the notion of the core product, which identifies what the consumers feel they are getting when they purchase the product. The core benefits derived when an overweight 45-year-old male purchases a USD 250 ten-speed bicycle is not transportation; it is the hope for better health and improved conditioning. In a similar vein, that same individual may install a USD 16,000 swimming pool in his backyard, not in order to obtain exercise, but to reflect the status he so desperately requires. Both are legitimate product cores. Because the core product is so individualized, and oftentimes vague, a full-time task of the marketer is to accurately identify the core product for a particular target market. Think of the core product as being the benefit sought.

Once the core product has been indicated, the actual product becomes important. This tangibility is reflected primarily in its quality level, features, brand name, styling, and packaging. Literally every product contains these components to a greater or lesser degree. Unless the product is one-of-a-kind (e.g. oil painting), the consumer will use at least some of these tangible characteristics to evaluate alternatives and make choices. In addition, the importance of each will vary across products, situations, and individuals. For example, for Mr. Smith at age 25, the selection of a particular brand of new automobile (core product=transportation) was based on tangible elements such as styling and brand name (choice=Corvette); at age 45, the core product remains the same, while the tangible components such as quality level and features become important (choice=Mercedes). While these primarily relate to physical goods, the branding, and packaging elements relate to services as well.

At the next level lies the augmented product. Every product is backed up by a host of supporting services. Often, the buyer expects these services and would reject the core-tangible product if they were not available. Examples would be restrooms, escalators, and elevators in the case of a department store, and warranties and return policies in the case of a lawn mower. Dow Chemical has earned a reputation as a company that will bend over backwards in order to service an account. It means that a Dow sales representative will visit a troubled farmer after-hours in order to solve a serious problem. This extra service is an integral part of the augmented product and a key to their success. In a world with many strong competitors and few unique products, the role of the augmented product is clearly increasing.

The outside of the three rings of the product – not illustrated in the exhibit – is referred to as the promised product. Every product has an implied promise. An implied promise is a characteristic that is attached to the product over time. The car industry rates brands by their trade-in value. There is no definite promise that a Mercedes-Benz holds its value better than a BMW. There will always be exceptions. How many parents have installed a swimming pool based on the implied promise that their two teenagers will stay home more or that they will entertain friends more often? Having discussed the components of a product, it is now relevant to examine ways of classifying products in order to facilitate the design of appropriate product strategies.

Figure 7.1.1: The Augmented Product and Actual Product

Classification of Products

It should be apparent that the process of developing successful marketing programs for individual products is extremely difficult. In response to this difficulty, a variety of classification systems have evolved that, hopefully, suggest appropriate strategies. The two most common classifications are: (a) consumer goods versus industrial goods, and (b) goods products (i.e. durables and nondurables) versus service products.

The traditional classification of products is to dichotomize all products as being either consumer goods or industrial goods. When we purchase products for our own consumption or that of our family with no intention of selling these products to others, we are referring to consumer goods. Conversely, industrial goods are purchased by an individual or organization in order to modify the product or simply distribute it to the ultimate buyer in order to make a profit or meet some other objective.

Classification of Consumer Goods

Products and services can be categorized in a number of ways. We will use these categories throughout the book because they are the most commonly referred to categories by marketers and because there are marketing implications for each. Consumer offerings fall into four general categories:

- Convenience offerings

- Shopping offerings

- Specialty offerings

- Unsought offerings

In this section, we will discuss each of these categories. Keep in mind that the categories are not a function of the characteristic of the offerings themselves. Rather, they are a function of how consumers want to purchase them, which can vary from consumer to consumer. What one consumer considers a shopping good might be a convenience good to another consumer.

Convenience Offerings

Convenience offerings are products and services consumers generally don’t want to put much effort into shopping for because they see little difference between competing brands. For many consumers, bread is a convenience offering. A consumer might choose the store in which to buy the bread but be willing to buy whatever brand of bread the store has available. Marketing convenience items is often limited to simply trying to get the product in as many places as possible where a purchase could occur.

The Life Savers Candy Company was formed in 1913. Its primary sales strategy was to create an impulse to buy Life Savers by encouraging retailers and restaurants to place them next to their cash registers and include a nickel—the purchase price of a roll of Life Savers—in the customer’s change.

Jason – Life Savers – CC BY-NC 2.0.

Closely related to convenience offerings are impulse offerings, or items purchased without any planning. The classic example is Life Savers, originally manufactured by the Life Savers Candy Company, beginning in 1913. The company encouraged retailers and restaurants to display the candy next to their cash registers and to always give customers a nickel back as part of their change so as to encourage them to buy one additional item—a roll of Life Savers, of course!

Shopping Offerings

A shopping offering is one for which the consumer will make an effort to compare and select a brand. Consumers believe there are differences between similar shopping offerings and want to find the right one or the best price. Buyers might visit multiple retail locations or spend a considerable amount of time visiting Web sites and reading reviews about the product, such as the reviews found in Consumer Reports.

Consumers often care about brand names when they’re deciding on shopping goods. If a store is out of a particular brand, then another brand might not do. For example, if you prefer Crest Whitening Expressions toothpaste and the store you’re shopping at is out of it, you might put off buying the toothpaste until your next trip to the store. Or you might go to a different store or buy a small tube of some other toothpaste until you can get what you want. Note that even something as simple as toothpaste can become a shopping good for someone very interested in her dental health—perhaps after she’s read online product reviews or consulted with her dentist. That’s why companies like Procter & Gamble, the maker of Crest, work hard to influence not only consumers but also people like dentists who influence the sale of their products.

If your favorite toothpaste is Crest’s Whitening Fresh Mint, you might change stores if you don’t find it on the shelves of your regular store.

Ben Lucier – Crest Toothpaste – CC BY 2.0.

Specialty Offerings

Specialty offerings are highly differentiated offerings, and the brands under which they are marketed are very different across companies, too. For example, an Orange County Chopper or Iron Horse motorcycle is likely to be far different feature-wise than a Kawasaki or Suzuki motorcycle. Typically, specialty items are available only through limited channels. For example, exotic perfumes available only in exclusive outlets are considered specialty offerings. Specialty offerings are purchased less frequently than convenience offerings. Therefore, the profit margin on them tends to be greater.

Note that while marketers try to distinguish between specialty offerings, shopping offerings, and convenience offerings, it is the consumer who ultimately makes the decision. Therefore, what might be a specialty offering to one consumer may be a convenience offering to another. For example, one consumer may never go to Sport Clips or Ultra-Cuts because hair styling is seen as a specialty offering. A consumer at Sport Clips might consider it a shopping offering, while a consumer for Ultra-Cuts may view it as a convenience offering. The choice is the consumer’s.

Specialty offerings, such as this custom-made motorcycle, are highly differentiated. People will go to greater lengths to shop for these items and are willing to pay more for them.

Wikimedia Commons – CC BY 2.0.

Marketing specialty goods requires building brand name recognition in the minds of consumers and educating them about your product’s key differences. This is critical. For fashion goods, the only point of difference may be the logo on the product (for example, an Izod versus a Polo label). Even so, marketers spend a great deal of money and effort to try to get consumers to perceive these products differently than their competitors’.

Unsought Offerings

Unsought offerings are those that buyers do not generally want to have to shop for until they need them. Towing services and funeral services are generally considered unsought offerings. Marketing unsought items is difficult. Some organizations try to presell the offering, such as pre-need sales in the funeral industry or towing insurance in the auto industry. Other companies, such as insurance companies, try to create a strong awareness among consumers so that when the need arises for these products, consumers think of their organizations first.

Classification of Industrial Goods

Consumer goods are characterized as products that are aimed at and purchased by the ultimate consumer. Although consumer products are more familiar to most readers, industrial goods represent a very important product category, and in the case of some manufacturers, they are the only product sold. The methods of industrial marketing are somewhat more specialized, but in general the concepts presented in this text are valid for the industrial marketer as well as for the consumer goods marketer.

Industrial products can be classified differently depending on the source. We are dividing the products into two categories. The first category are types of product used in production of products:

Raw materials: products in their crude form that will be used in other products

Installations: major capital investment items of facilities and equipment

Component parts: manufactured products that are a part of another good

The second category are products used in the running of the business:

Accessory equipment: the equipment found in an office setting such as furniture or communication devices

Business services: services performed by a third party such as security, accounting, etc.

MRO supplies: (maintenance, repair, and operating): products that are used in daily operations

The Product Mix

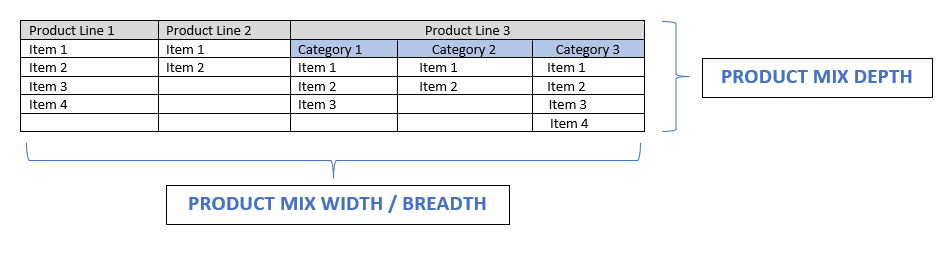

Most organization have thousands of individual products (product items) they offer to potential buyers. All the offering of an organization is known as the product mix. Trying to manage thousands of products and strategies is unrealistic and would be a waste of resources. To help manage all the items in the mix, firms organize the items into lines and categories. Product lines are groupings of similar product items. The grouping is up to the organization but might be based on functionality, target market, or geography. Product categories are sub-groupings within a product line.

Finally, product mix width (or breadth) describes the number of lines in a mix. If a product mix has many lines, then it is wide. If it has limited lines, then it is narrow. The product mix depth describes the number of items in a line. If there are many items, it is deep. If it has limited items, it is shallow. As the graphic below illustrates, some product lines may have a couple items, some may have many, and some may even have different categories with differing numbers of items.

Figure 7.1.2: Product Mix

You Try It!