5 – Narration

5.1 Defining Narration

So far, we have analyzed the main constituents of the story, or, as we have called them, the existents of the storyworld: events, environments, and characters. But the storyworld only comes to exist because someone (a narrator) tells a story to someone else (a narratee). This is what we call narration, a communicative act that does not happen in the storyworld or at the level of the story. Narration is part of discourse, which constitutes the second level in our semiotic model of narrative.

Narrative discourse is the communication between the implied author and the implied reader of a narrative (see #Fig. 1.5 ). The ‘implied author’1 is implied because it does not have an explicit or independent reality, as the real author does, but must be reconstructed by the reader from the narrative itself. It is important in this sense to distinguish the implied author from the narrator of the story. The implied author does not tell anything; it does not have a voice. It is simply the organizing principle of discourse, which includes the narrator and the other aspects of the narration.2 Every narrative has an implied author, even if it does not have a real author (e.g., a computer-generated text) or it has many of them (e.g., collaborative fiction). Similarly, every narrative has an implied reader, which is the ideal reader addressed by narrative discourse.3

Ben’s Bonus Bit – Why Narrative Theory? Avoiding Common Pitfalls

What is gained by adopting this onion-like, semiotic model of storytelling? Why bother distinguishing implied authors from real or from narrators? This is the most jargon-heavy section of our textbook, but narrative theory provides a few key benefits to students studying fiction. First, insisting on division between real author, implied author, and narrator avoids the authorial or intentional fallacy—the notion that an author’s intentions should limit or control the ways a text is interpreted—which can severely restrict the creativity of student essays. As we discussed in the case of J. K. Rowling’s controversial tweets and blog posts in the previous chapter, the relative importance of the author in shaping our understanding of a text is a matter of some debate and has been a salient point of contention among scholars since the rise of New Criticism in the 1940s. The New Critics, including T.S. Eliot, insisted that close textual analysis is the key to making successful interpretive claims. While New Criticism eventually gave way to Feminism, Structuralism, Deconstruction theory, Reader-Response, and other movements in literary criticism, the practice of close reading remains essential to essay writing at the collegiate level. Narrative Theory encourages close reading by insisting on division between author’s biography and analysis of implied author or narrator. Score one for the New Critics.

Second, students are occasionally tempted to draw moral or moralistic conclusions about an author based on the ideas or behaviors of a narrator. This is almost always a grand interpretive mistake, leading to judgmental essays with non-academic tones. These novice readers severely underestimate the creativity of writers, who often invent unreliable or even evil narrators. We have already mentioned Vladimir Nabokov’s controversial novel Lolita and its horrible narrator Humbert Humbert. To ascribe any of Humbert’s vile ideas to the novel’s real author amounts to slander or defamation and gives aid and intellectual cover to censorship efforts. Students, who are often not creative writers themselves, have difficulty imagining that an author could write so eloquently from the perspective of a pedophile without himself owning those impulses, yet Nabokov condemned pedophilia repeatedly throughout his life. Indeed, Nabokov’s disdain for Lewis Carroll, a writer who has been accused of pedophilia, bleeds through in Lolita itself. Narrative theory allows us to escape these tempting misreadings by acknowledging fiction-writing as a craft and the artifice of storytelling from the jump. If we wish to write sophisticated, intellectually generous academic prose (and we should wish this), building a theoretical wall between judgment and analysis is an important psychological step. This advice does not preclude moral judgment or consideration for morality in answering the “so what?” question in any essay, but it does ward off students from non-academic rhetorical moves, which are common in Introduction to Fiction courses.

In this chapter, we will examine in some detail the different elements of narration. Then, in the next chapters, we will look at other key aspects of discourse, namely language and theme. Of course, the questions raised by the analysis of discourse often cross over to the story. Therefore, we must always keep in mind the distinction between these two levels of narrative.

This is particularly important when we discuss narration because the object of narration is the story itself. We can only interpret the storyworld (with all its events, environments, and characters) from the story told by the narrator to the narratee. While neither the narrator nor the narratee need to exist as such in the storyworld, these figures of discourse can also be characters in the story, a complication that we will try to clarify in the following pages.

First, we need to define more precisely what we mean by narration and the relationship between narration and the story being narrated. Then we will look more closely at the two figures of discourse involved in narration, the narrator and the narratee, outlining the types most commonly found in prose fiction. We will then examine the concept of focalization, an important and closely related aspect of narration, which refers to the point of view or perspective adopted by the narrator of the story. Next, we will discuss in more detail the basic means by which narrators can represent events, characters, and environments: telling and showing. But narrators, besides representing the existents of the storyworld, often also make comments about them. To conclude the chapter, therefore, we will consider the use of explicit and implicit commentary in prose fiction.

5.2 The Expression of Narrative

Narration is the communicative act of telling a story. The figures of discourse involved in this act are the narrator (who tells the story) and the narratee (who listens to, or reads, the story). The story is what is being told. Narration is how it is being told. This involves a series of prior decisions, attributed to the implied author (and, ultimately, to the real author) about who the narrator will be, what kind of knowledge the narrator will have about the existents of the storyworld, what narrative techniques the narrator will employ to convey the story, and so on. All these decisions, taken together, define the expression of narrative, that is, the process of communicating the story.

Here, we are mostly concerned with the narration of a story, which is an instance of narrative discourse. But prose fiction can also include narration within the story itself.4 For example, in One Thousand and One Nights a narrator tells the story of a sultan who kills all of his new wives after the first night, until Scheherazade keeps him in suspense for 1,001 nights by telling him different stories (see Fig. 5.1). The narrator of these stories is of course Scheherazade herself. But many of the stories she tells include characters who tell other stories in their turn. Inception! The result is an intricate structure of embedded or subordinated narratives. While most short stories and novels are not as complex as One Thousand and One Nights, the technique of embedding narratives, also known as ‘a story within a story,’ is a common literary device. Such a technique, however, does not affect the general framework of our semiotic model of narrative. Regardless of how many embedded stories we find in a narrative, every story is framed by a higher level of discourse, which includes its narration.5 If that narration is part of another story, then the whole structure is repeated, until we reach the highest level of narrative, which links an implied author with an implied reader.

Fig. 5.1 Édouard Frédéric Wilhelm Richter, Scheherazade (before 1913), Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Edouard_Frederic_Wilhelm_Richter_-_Scheherazade.jpg

In some cases, short stories and novels consciously play with the different levels of narrative, either to transgress them or simply for comic effect. For example, Laurence Sterne’s novel Tristram Shandy is narrated by the eponymous character, who supposedly tells his life story. But the narrator constantly crosses the boundaries of narration to directly address the reader (‘breaking the fourth wall’ in film) or to call into question the verisimilitude of the narrative itself. In postmodernist fiction of the late 20th century, there are quite a few examples of this sort of transgression, often using the so-called “mise en abyme“ device, in which embedding stories within stories creates unresolvable paradoxes, as in André Gide’s The Counterfeiters, where one of the characters intends to write the same novel in which he appears. Other types of frame tales have existed in prose or narrative poetry for millennia, with Homer’s The Odyssey, Dante’s “The Divine Comedy,” and Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales among them.

All these self-conscious devices, rather than contradicting the general framework of narrative that we have been presenting here, are exceptions that confirm the rule. The fact is that most fictions establish, explicitly or implicitly, a clear distinction between the level of discourse and the level of story. Narration, which occurs at the level of discourse, is the communicative act between a narrator and a narratee responsible for expressing or representing all the elements of the story.

5.3 Narrators and Narratees

The narrator of a story is the figure of discourse that tells the story. This definition seems simple enough, but in practice there are several complications. Similarly, the narratee is the figure of discourse to whom the narrator tells the story. Again, there are quite a few practical considerations about this figure that we need to clarify.

In most short stories and novels, the narrator can be easily identified by asking the question: ‘who speaks?’ (or ‘who writes?’ when the story is supposedly told in writing). Often, however, this narrator does not have a name or a clear identity, so we speak of an unknown narrator, even though we can sometimes infer details about his or her life, personality, or opinions from the narration itself. In other cases, the narrator is just a voice with no subjective dimension whatsoever.

One aspect of this voice that is usually obvious from the narrative is the person status of the narration. Founded on a grammatical distinction, the notion of person allows us to discern the underlying relationships between the narrator, the narratee, and the characters in the story:

- First-person narrator: the narrator tends to use the first person quite often (“I went out at five o’clock”), even if other grammatical persons exist in text. This kind of narrative voice is commonly found in stories told by a narrator who is also the protagonist, or at least a relevant character, in the plot. The narratee may or may not be explicit. For example, J. D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye (Fig. 5.2) is narrated by its seventeen-year-old protagonist, Holden Caulfield, who naturally tends to talk quite a lot about himself

- Second-person narrator: the narrator uses the second person most of the time (“You went out at five o’clock”). The second person explicitly refers to the narratee, which in some cases might be the narrator himself. This kind of voice is difficult to sustain throughout the narrative and has generally been tried only in experimental novels, such as Italo Calvino’s If on a Winter’s Night a Traveller, where the framing narrative directly addresses a reader of the novel (narratee). It is more common in short or flash fiction (Jamaica Kincaid’s “Girl” or Akwaeke Emezi’s “Muzik di Zumbi”)

- Third-person narrator: the narrator uses the third person most of the time (“The marquise went out at five o’clock”). This is, by far, the most common narrative person in prose fiction. The narrator may or may not be a character in the story. Similarly, the narratee may be explicit or implicit. There are countless examples of this perspective. One of them is John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath, told by a narrator who does not participate in the story.

Fig. 5.2 First-edition cover of The Catcher in the Rye (1951) by J. D. Salinger, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_Catcher_in_the_Rye_ (1951,_first_edition_cover).jpg

It is also important to make a distinction related to the previous classification between two kinds of narrators:

- External narrator: the narrator only exists as a figure of discourse. She is not a character in the story and only speaks from outside of the storyworld. Once again, The Grapes of Wrath is a good example.

- Internal narrator: on the other hand, besides being a figure of discourse, an internal narrator is also an existent in the storyworld. Whether he is actually a character depends on his participation in the story, which can be extensive (e.g. a narrator who is also a major character, like the husband in Raymond Carver’s “Cathedral”) or limited (e.g. a narrator who is just a secondary character, like Dr. Watson in “A Scandal in Bohemia” and many other Sherlock Holmes stories). While it is also possible for the narrator to be part of the storyworld without being a character in the story, this is rare and not easy to distinguish from an external narrator.

There are also certain types of narrative that seem to lack a narrator, for example epistolary novels like Pierre Choderlos de Laclos’ Les Liaisons Dangereuses, which consists entirely of letters exchanged between the different characters. But even in such cases there is an implicit figure of discourse, a narrator, who has arranged and edited the letters to tell a certain story. What is lacking here, therefore, is not the narrator, but the narrative voice or an explicit narration.

Finally, we should not forget that narration is itself a process, a communicative act carried out by a narrator at a certain time and place. The spatial relationship between the narrator’s environment and the environments of the storyworld is usually only relevant if the narrator is internal to the storyworld. But the temporal relationship between narration and the events of the story has some influence on the form of narrative discourse, even if the temporalities of the narrator and the storyworld belong to different levels. When considered in relation to the events arranged in the plot, there are basically three kinds of narration:6

- Ulterior narration: events are supposed to have already happened when the narrator tells the story. This is the most common form of narration, which uses past tense as a standard narrative tense. Most short stories and novels are narrated using this convention.

- Anterior narration: events are not supposed to have happened yet when the narrator tells the story. This form, which tends to use the future tense, is rare in prose fiction. We generally only find it in prophecy or visionary narratives, for example in the Bible.

- Simultaneous narration: events are supposed to happen while the narrator tells the story. This form is usually only found in diaries or novels that experiment with narrative voice, as in Michel Butor’s Second Thoughts, narrated in present tense and addressed by the narrator to himself.

As with any communicative act, narration involves a sender, the narrator, but also a recipient, the narratee. The narratee is situated at the same level as the narrator. But narratees are generally not as easy to identify as narrators. While they are sometimes explicitly mentioned in the narrative, most often they are only implicit figures, never mentioned or even acknowledged.

Like narrators, narratees can be external or internal to the storyworld. External narratees are generally left implicit and could easily be mistaken for implied or real readers. Even when the narrator addresses the narratee as “reader,” for example in Charlotte Brontë’s novel Jane Eyre, it does not mean that she is in fact addressing the real (or even the implied) reader. In this case, the label “reader” is simply the term employed by the narrator to address an otherwise undetermined external narratee. Certainly, it seems that the (implied) author has chosen to put in the mouth of the narrator a term that refers to the (implied) reader. But such transgression of the levels of narrative (see Chapter 1) is only superficial. In fact, the narrator of a story can never address the implied reader, which is necessarily external to the discourse that brings the narrator herself into existence.

Internal narratees can also be left implicit, in which case it is difficult to distinguish them from external ones. When they are identified during the narration, internal narratees tend to be minor characters (e.g. the stranger who listens to the story told by Jean-Baptiste Clamence in Albert Camus’ The Fall) or other existents in the storyworld (e.g. the unnamed individual to whom the narrator of Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Tell-Tale Heart” addresses his plea). There are also instances of collective narratees, when the narrator addresses an audience instead of a single recipient (e.g. the sailors who listen to Marlow’s story in The Heart of Darkness or the academic public of the ape Red Peter in Kafka’s “A Report to an Academy”), as well as cases where the narrator and the narratee are identical, for example when the story is narrated in an intimate diary (e.g. Helen Fielding’s Bridget Jones’s Diary).

Finally, we should not forget that narration in prose fiction is sometimes shared by multiple narrators and can address multiple narratees, with the different parts of the narrative presented as a sequence of chapters, as in William Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury, or intertwined in more complex arrangements, as in Vladimir Nabokov’s Pale Fire.

5.4 Focalization

Identifying the narrator of a story is generally not enough to properly understand the mechanism of narration. Some narrators seem to move in and out of different characters’ consciousness with ease, while others remain attached to a single character’s perspective or constrain themselves to narrating observable events, without ever penetrating any character’s consciousness or presuming to know their thoughts. These differences can be better grasped with the concept of focalization, a technical term that is commonly used in narratology to replace the more ambiguous, but still popular, concept of point of view.

If the response to the question ‘who speaks?’ in a narrative is ‘the narrator,’ focalization responds to the additional question ‘from which perspective or point of view?’ Focalization can be defined as the perspective adopted by the narrator when telling the story, which is basically determined by the position of the narrator in relation to the characters in the storyworld. We can identify two fundamental types of focalization:7

- Inward focalization: The narrator tells the story from the subjective perspective of a focal character, revealing her inner thoughts and feelings as if he could somehow enter inside or read her mind. In the case of a first-person narrator, of course, focalization tends to be inward, even if the narrator might be speaking from the perspective of his younger or infant self, as in many autobiographical narratives, such as Charles Dickens’ Great Expectations. A third-person narrator, even one that is external to the storyworld, can also be inwardly focalized, when he adopts or tells the story from the subjective perspective of one of the characters. A classic example is Henry James’s novel The Ambassadors, narrated by an external narrator from the perspective or point of view of its protagonist, Lambert Strether.

- Outward focalization: The narrator tells the story without presuming to know or have access to the subjective perspective of any character, simply reporting what can be observed from the outside. When the narrator is internal to the storyworld, even if she doesn’t participate directly in the events of the story, outward focalization usually involves a certain degree of subjectivity, given that the narrator herself is a focal character. It is difficult in those cases to determine with precision whether the narration is outwardly or inwardly focalized. If the narrator is external, on the other hand, it is much simpler to sustain an outwardly focalized narration, where the narrator acts like a camera, recording everything that happens in the storyworld without entering the consciousness of any of the characters. Examples of this type of focalization can be found in Dashiell Hammett’s detective novels and short stories, such as The Maltese Falcon (Fig. 5.3).

Inward and outward focalization may be fixed throughout the narrative, as in the examples provided above. But focalization can also be variable, for example when the narrator alternates between inward and outward focalizations (e.g. Stendhal’s The Red and the Black), or multiple, when the narrator uses different focal characters to tell the story (e.g. George R. R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire).

Fig. 5.3 Promotional still from the 1941 film The Maltese Falcon, published in the National Board of Review Magazine, p. 12. L-R: Humphrey Bogart, Mary Astor, Barton MacLane, Peter Lorre, and Ward Bond, Public Domain, https:// commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Maltese-Falcon-Tell-the-Truth-1941.jpg

Another important aspect of narration, which is related (and often confused) with focalization, is the degree of knowledge that the narrator has about the existents of the storyworld, in particular about the inner thoughts and feelings of the characters. Here, we are implicitly asking the question ‘how much does the narrator know?’ In this sense, we can distinguish three types of narrators:

- Omniscient: The narrator is like a God of the storyworld, knowing everything about its existents, including the internal or psychological states of all characters and the unfolding of events. In this case, focalization is often variable and multiple, changing from outward to inward and from one character to another as the narrator thinks appropriate, which might give the impression that there is in fact no focalization at all. Many classic short stories and novels are narrated with this sort of God-like narrator, for example J. R. R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings.

- Limited: The narrator has only limited knowledge about the internal or psychological states of one or some of the existents in the storyworld. This is quite common in inwardly focalized fictions, where the narrator only knows what the focal character or characters think and perceive, while having no access to the consciousness of other characters. When the focal character is the narrator himself, as in first-person narratives, his perspective is generally limited. An example of this kind of narration may be found in Jorge Luís Borges’s short story “Funes the Memorious,” where an unnamed first-person narrator recounts his relationship with a man who remembers absolutely everything.

- Objective: The narrator has no knowledge about the internal or psychological states of any of the characters in the storyworld and can only report what can be observed from the outside. The perspective of an objective narrator, which tends to be outwardly focalized, can be compared to that of a movie camera. While both the camera and the objective narrator need to select and frame their perceptions, they can only record what can be externally perceived in the storyworld, but not what characters think or feel. Ernest Hemingway’s “The Killers” is a minimalist short story about a pair of criminals in a restaurant which is narrated with this kind of camera-eye perspective.

5.5 Telling and Showing

Already established in Classical poetics, particularly by Plato and Aristotle, the distinction between ‘telling’ (diegesis) and ‘showing’ (mimesis) can help to clarify key aspects of narrative discourse. Telling refers to the representation of the story through the mediation of a narrator, who gives an account and often interprets or comments on the events, environments, or characters of the storyworld. Showing, on the other hand, is the direct representation of the events, environments, and characters of the story without the intervention of a narrator, leaving readers or spectators to make their own inferences or interpretations.

The distinction between these two concepts is clear when we compare a story told by a third-person narrator (telling) and the same story represented as a dramatic play, with a stage imitating the environments, actors playing the characters, and events being enacted as if they were happening in the storyworld (showing). However, using this same pair of concepts to distinguish between different forms of narration is not so straightforward.

We have already seen that all narratives have a narrator, even if the narrator can adopt an outward focalization (e.g. camera-eye perspective) or even lack a perceptible narrative voice (e.g. the editor of a set of letters).

In this sense, all narration is a form of telling (diegesis), not showing (mimesis). But we have also seen that there can be different forms of narration. In some cases, the narrator conveys the words of characters using his own voice, as in “The detective claimed that he never suspected his girlfriend wanted to kill him.” In other cases, the narrator quotes the words that were supposedly spoken by the characters themselves, as in “‘How could I suspect she wanted to kill me?’ said the detective.” The first type of narration can be qualified as telling, while the second is a derived form of showing. In this case, the distinction is not based on the presence or absence of a narrator, but rather on his prominence or degree of involvement in the narration.

In prose fiction, telling and showing usually involve the use of two different narrative methods to represent the events of the plot:

- Summary: A summary narrates events by compressing their duration. For example, a narrator might tell about a long war by saying, “Battles were won and lost, many died, and at the end no one felt victorious.” A single sentence summarizes years of war, with all its battles and other significant events. In general, summary brings narration closer to the ideal of telling. In the same way that description is the telling of environments and characters, summary is the telling of events.

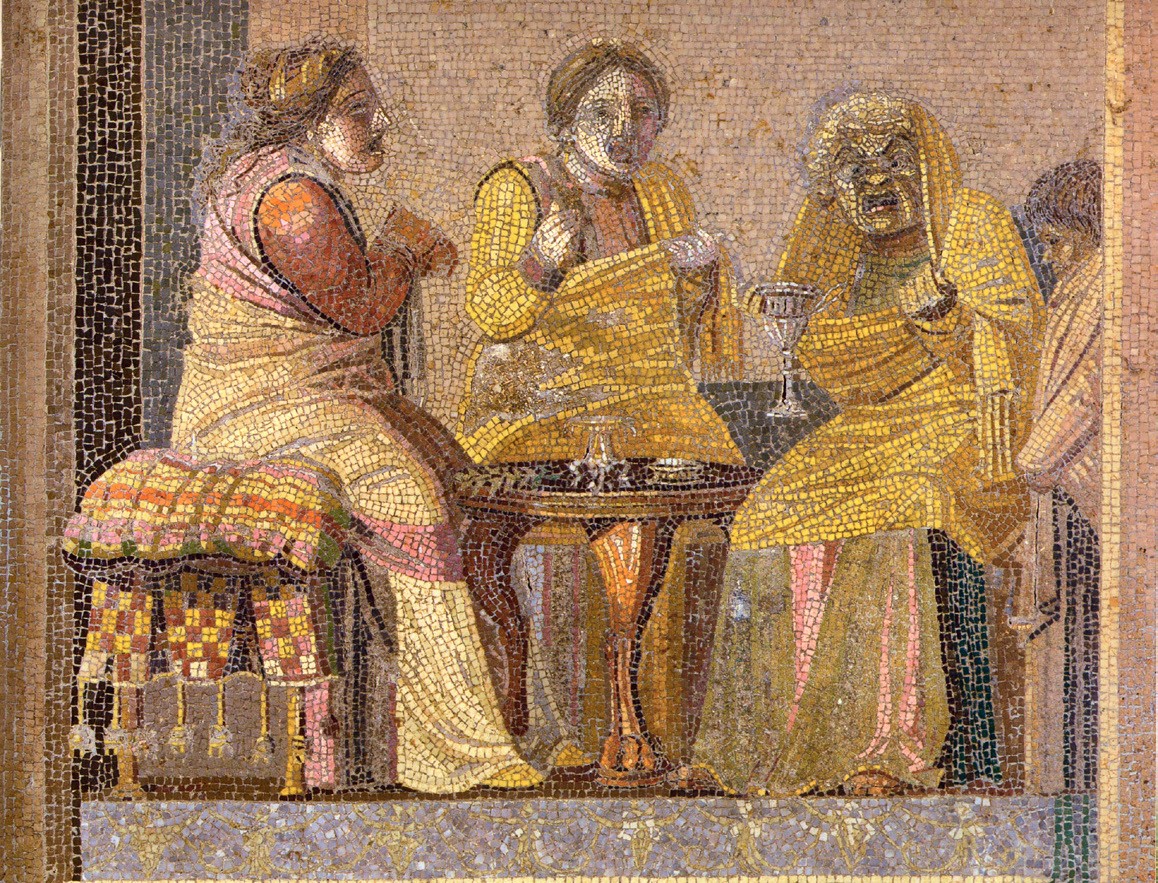

- Scene: A scene narrates a sequence of events in enough detail to create the illusion that they are unfolding in front of the narratee (and ultimately, the reader). Usually, the illusion is created by quoting dialogue in direct speech, intersected with brief descriptions of the environment and the characters, as well as some narration of the characters’ actions. This method, which is already found in Ancient epic, is called “in-scene storytelling” and seems to be inspired by drama, which has traditionally been considered the most lifelike method of representing a story (see Fig. 5.4). Thus, scene brings narration closer to the ideal of showing.

Fig. 5.4 Theatre scene: two women making a call on a witch (all three of them wear theatre masks). Roman mosaic from the Villa del Cicerone in Pompeii, now in the Museo Archeologico Nazionale (Naples). By Dioscorides of Samos, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pompeii_-_Villa_del_Cicerone_-_Mosaic_-_MAN.jpg

Despite the recurrent debates that oppose telling to showing, the fact is that both forms of narration are commonly found in most short stories and novels. Neither of them is superior to the other, and both have their own uses and limitations.

Ben’s Bonus Bit – Telling of Emotions

In the instruction of creative writing, novice writers are encouraged to avoid the direct telling of character emotions8. “John was sad,” for example, misses opportunity to reach in-scene storytelling. What behaviors do sad people exhibit? What posture, gestures, and other nonverbals display sadness? What things do sad people say? If the narration has an inward focalization, attached to John, what might he think other than “I am sad” that would reveal his blooming depression? Each choice to “show” preserves reader’s role as arbiter of meaning. Direct telling of character emotions runs the risk of infantilizing readers, robbing them of one of the principle pleasures of reading.

Of course, this is an over-simplification of a truism: that readers prefer showing to telling, in-scene storytelling to summary, and in medias res action to exposition. Telling of emotions exists prominently in didactic fiction, first-person narratives, and in epiphany moments. Some of the most memorable lines in fiction are “telling.” We have already mentioned the boy’s epiphany at the end of Joyce’s “Araby” (“I saw myself as a creature driven and derided by vanity; and my eyes burned with anguish and anger“). Consider the opening lines of Ralph Ellison’s classic story (and novel chapter) “Battle Royal”: “It goes a long way back, some twenty years. All my life I had been looking for something, and everywhere I turned someone tried to tell me what it was. I accepted their answers too, though they were often in contradiction and even self-contradictory. I was naive. I was looking for myself and asking everyone except myself questions which I, and only I, could answer. It took me a long time and much painful boomeranging of my expectations to achieve a realization everyone else appears to have been born with: That I am nobody but myself. But first I had to discover that I am an invisible man!” Nary an in-scene moment to be found. All exposition, telling, symbolism, and internal focalization. Where is the significant, sensory detail that marks “good writing”? Truth is that strong prose contains a mixture of showing and telling, even if there are moments where narrators suppress readers’ “interpretive rights.”

For students of fiction, there’s real analytical hay to make out of distinguishing between showing and telling moments. Essays about point of view, focalization, narration, or even characterization occurring in the first-person may successfully speculate about reader response by considering how and when authors shift the interpretive burden to readers. Essays that make broad claims about “the reader” without the aid of textual analysis are invariably less successful.

5.6 Commentary

Narrative discourse can do more than just tell a story through the voice of a narrator. It can also contain commentary, which consists of any pronouncement of the narrator that goes beyond a description or account of the existents of the story. While commentary, like the rest of narration, is expressed by the narrator’s voice, it can also include messages sent by the implied author to the implied reader through the narrator’s voice, even if the narrator is unaware of them. These moments can be critical in stories that otherwise emphasize “showing” via in-scene, linear, real-time storytelling. Commentary, which is certainly “telling,” may nudge readers toward consideration of theme.

There are two basic forms of commentary: explicit and implicit.9 Explicit commentary is easier to recognize and understand, as it consists of a straightforward message found in the narration. There are three types of explicit commentary that the narrator can make about the story and one about the narration itself:

- Interpretation: the narrator explains the meaning, relevance, or significance of the existents in the storyworld. In Balzac’s series of novels The Human Comedy, for example, narrators often provide interpretations that contextualize and analyze the social implications of the various behaviors of the characters, almost like a sociologist would do

- Judgement: the narrator expresses a moral opinion or another form of personal evaluation of the existents in the storyworld. In Henry Fielding’s Tom Jones, for example, the narrator constantly gives his opinion about the events and characters of the story, in keeping with his moralizing intentions

- Generalization: the narrator extrapolates the existents of the story to reach general conclusions about his own world (or the lifeworld of the reader). This is most common in philosophical novels, such as Milan Kundera’s The Unbearable Lightness of Being, where the narrator comments on the characters and reflects on the events in the novel by connecting them with philosophical notions or events in European history

- Reflection: the narrator comments on his own narration or other aspects of narrative discourse. This form of self-reflective commentary is already found in early examples of the novel, for instance in Cervantes’ Don Quixote, where the narrator often pauses to reflect on the task of narrating his story, particularly in the second part of the book, when he feels the need to defend his creation from a plagiarizer. Vladimir Nabokov, who we’ve already mentioned, uses this device frequently in both Lolita and Pale Fire. If reflection bleeds into discussion of the fiction as fiction, the device is metafiction.

Implicit commentary is a form of irony, a use of discourse to state something different from, or even opposite to, what is actually meant. The irony might be at the expense of the characters or at the expense of the narrator herself. Depending on which levels of narrative it crosses, we can distinguish two basic kinds of implicit commentary in prose fiction:

- Ironic narrator: the narrator makes a statement about the characters or events in the story that means something different, even the opposite, to what is being stated. Thus, the narrator is being ironic. In this case, the irony is at the expense of the characters in the story but can be understood by the narratee (and eventually by the reader). A classic example of this form of irony is the first sentence in Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice: “It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune must be in want of a wife.” In fact, the narrator thinks that this is far from a universal truth, except under the assumptions of a narrow-minded bourgeoisie—the kind of people worthy of Lizzy Bennet’s scorn—as is made clear in the rest of the novel

- Unreliable narrator: the narrator makes statements that contradict what the implied reader can know (or infer) to be the real intention or meaning of the narrative discourse. In this case, it is the implied author who is being ironic, by communicating indirectly with the implied reader at the expense of the narrator. The narrator in this case is said to be unreliable.10 In Nikolai Gogol’s short story “Diary of a Madman,” for example, the narrator, a minor civil servant, becomes increasingly unreliable as he descends into madness, making statements whose irony (and comic effect) are only accessible to the implied reader (Fig. 5.5). Another celebrated example of an unreliable narrator is Gulliver in Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels, where irony turns into satire, as the gullible narrator tells of his misadventures amongst exotic creatures without ever suspecting that they are meant to ridicule the absurdities and pretensions of human society.

Narrators may be unreliable because they are naive, ignorant, braggadocious, mad, or morally bankrupt. Pi Patel in Yan Martel’s The Life of Pi separates himself from reality in order to survive. Alex in Anthony Burgess’ A Clockwork Orange is deluded and lies to readers. Huck in The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn tells readers that helping the runaway, Jim, is wrong. Implied readers know Huck, a child in antebellum times, is naive and indoctrinated by a racist society. Mark Twain, both the real author and the implied conception of him in the novel, counts on readers to see Huck’s naivete as part of a larger condemnation of slavery.

Fig. 5.5 Illustration of Nikolai Gogol’s short story ‘Diary of a Madman’ (1835) by Ilya Repin, Public Domain, https:// commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/ File:Repin_IE-Illustraciya-Zapiski- sumasshedshego-Gogol_NV4.jpg

Ben’s Bonus Bit – Abuse of “The Reader”

For students writing essays about narration, especially unreliable narration, the Narrative Model’s insistence on distinction between implied readers and real readers with modern lifeworlds is vital to acknowledging how readers’ values and attitudes change over time. Mark Twain’s implied reader of The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn is certainly quite different from you, a college student in the 21st century who is aware of post-Newtonian physics (Einstein, relativity, and quantum theory), DNA, vaccines, blood types, electronics, neuroscience, man’s impact on the environment in the Anthropocene, and all of the historical events inaccessible to literate 19th-century Americans. Your racial attitudes are almost certainly an order of magnitude more progressive and tolerant than even the most forward-thinking reader in 1884. Despite Samuel Clemens’ implied author’s compassion for Jim, Twain himself expressed a seemingly hypocritical racism towards Native Americans11.

The semiotic model encourages readers to avoid misuse of the ubiquitous “the reader,” which implies a monolithic, universal response to fiction, flattening legitimate difference in interpretation. The best essays engage with ambiguity in fiction, which naturally produces disagreement among readers. Indeed, your essay might not have reason to exist without interpretive dispute. Using “readers” instead of “the reader” is a small but generous concession that preserves student authors’ ability to make reader response claims while avoiding over-generalization or marginalization of minority voices. Even better is to draw distinction between the likely attitudes/reactions of implied readers (as imagined by a text’s author) and meaning-making by modern/current readers of different backgrounds. At the very least, student authors should consider and preempt alternative-but-plausible interpretations in Rebuttal Sections (often arriving just before a concluding paragraph or scattered throughout an essay). Just as it aids in avoiding the intentional fallacy, adopting the semiotic model in analyses prevents rhetorical missteps when considering the other end of the communication chain (receivers, or readers).

5.7 Summary

- An element of narrative discourse, narration is the communicative act between a narrator and a narratee that expresses or represents all the existents of the story (characters, events, and environments).

- Narrators (as well as narratees) can be external or internal to the story. Moreover, narrators can speak in the first, second, or third person. And they can narrate events that have already happened, have not yet happened, or are happening at the same time as they are being told.

- When telling a story, narrators can adopt the subjective perspective of one or more of the characters (inward focalization) or limit themselves to observable events without entering any of the characters’ consciousnesses (outward focalization).

- Similarly, narrators can know everything about the inner thoughts of characters and the unfolding of events (omniscient), or they can have only partial information about one or more of the characters (limited), or they can only know what can be perceived with the senses (objective).

- Depending on the prominence or degree of involvement of the narrator in the narration, we can distinguish two different narrative methods: telling (summary) and showing (scene).

- Beyond telling and showing, narrators can also make explicit and implicit commentary on the story, sometimes at the expense of characters (ironic narrator) or themselves (unreliable narrator).

- In essay writing about narration, avoid confusing authors (real and implied) from narrators and to avoid over-generalization of reader response (by using “readers” and including rebuttal).

Licenses and Attributions:

CC licensed content, Shared previously:

Ignasi Ribó, Prose Fiction: An Introduction to the Semiotics of Narrative. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2019. https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0187

Version History: Created new verso art. Added quick links. Bolded keywords. Made minor phrasing edits for American audiences. Adopted MLA style for punctuation. Changed paragraphing for PressBooks adaptation. Moved footnotes to endnotes. Added references to Jamaica Kincaid’s “Girl,” Akwaeke Emezi’s “Muzik di Zumbi,” Yan Martel’s The Life of Pi, Anthony Burgess’ A Clockwork Orange, and Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. Added vocabulary: in-scene storytelling and metafiction. Included “Ben’s Bonus Bits,” with a host of new vocabulary. Altered end-of-chapter Summary to include “Ben’s Bonus Bit” material, October, 2021.

Linked bolded keywords to Glossary and improved Alt-image text for accessibility, July, 2022.

End Notes

- Wayne C. Booth, The Rhetoric of Fiction (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1983).

- Seymour Benjamin Chatman, Story and Discourse: Narrative Structure in Fiction and Film (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2000), pp. 147–51.

- Wolfgang Iser, The Implied Reader: Patterns of Communication in Prose Fiction from Bunyan to Beckett (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1995).

- Shlomith Rimmon-Kenan, Narrative Fiction: Contemporary Poetics (London, UK: Routledge, 2002), pp. 94–97, https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203426111

- See Gérard Genette, Narrative Discourse: An Essay in Method (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1990), pp. 25–32.

- Rimmon-Kenan, pp. 90–102.

- Based on Genette, pp. 189–211.

- See “Showing and Telling” in Janet Burroway’s Writing Fiction.

- Chatman, pp. 228–60.

- Booth, pp. 149–68.

- See Joseph L. Coulombe, “Mark Twain’s Native Americans and the Repeated Racial Pattern in ‘Adventures of Huckleberry Finn'” in American Literary Realism Vol. 33, No. 3 (Spring, 2001), pp. 261-279 (19 pages).

References

Booth, Wayne C., The Rhetoric of Fiction (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1983).

Chatman, Seymour Benjamin, Story and Discourse: Narrative Structure in Fiction and Film (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2000).

Coulombe, Joseph L. “Mark Twain’s Native Americans and the Repeated Racial Pattern in ‘Adventures of Huckleberry Finn'” in American Literary Realism Vol. 33, No. 3 (Spring, 2001), pp. 261-279

Genette, Gérard, Narrative Discourse: An Essay in Method (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1990).

Iser, Wolfgang, The Implied Reader: Patterns of Communication in Prose Fiction from Bunyan to Beckett (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1995).

Rimmon-Kenan, Shlomith, Narrative Fiction: Contemporary Poetics (London, UK: Routledge, 2002), https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203426111

The world of the story, which includes different types of existents (events, environments, and characters).

A change of state occurring in the storyworld, including actions undertaken by characters and anything that happens to a character or its environment. Also called a “plot point.”

Everything that surrounds the characters in the storyworld.

An entity with agency in a storyworld.

The figure of discourse that tells the story to a narratee.

The figure of discourse to whom a story is told by the narrator.

The means through which a narrative is communicated by the implied author to the implied reader.

The projection of the real author in the text, as can be inferred by the reader from the text itself.

The virtual reader to whom the implied author addresses its narrative, and whose thoughts and attitudes may differ from an actual reader.

A form of writing where two or more authors share creative control of the narrative.

A relevant meaning identified by an interpreter in narrative discourse.

From film studies, the perspective or point of view adopted by the narrator when telling the story.

The representation of a story through the mediation of a narrator, who gives an account and often interprets or comments on the events, environments, or characters of the storyworld.

The direct representation of the events, environments, and characters of a story without the intervention (or, in the case of narrative showing, with minimal or limited intervention) of a narrator.

Any pronouncement of the narrator that goes beyond a description or account of the existents of the storyworld.

Semiotic representation of a sequence of events, meaningfully connected by time and cause.

A literary device that embeds self-reflecting or recursive images to create paradoxical narrations (from French, ‘placed into an abyss’).

A narrator or narratee who is a figure of discourse but not an existent of the storyworld.

A narrator or narratee who, besides being a figure of discourse, is also an existent of the storyworld, particularly a minor or major character.

Narration from the subjective perspective or point of view of one or more focal characters.

Narration that avoids taking the subjective perspective or point of view of any of the characters.

A narrator who knows everything about the existents of the storyworld, including the internal or psychological states of all characters and the unfolding of events.

A narrator who has only limited knowledge about the internal or psychological states of one or some of the existents in the storyworld.

A narrator who has no knowledge about the internal or psychological states of any of the characters in the storyworld and can only report what can be observed from the outside.

A category of fiction where a story is recounted through narration. While all stories contain at least implied narrators, diegetic fiction “tells” through a distinct perspective.

A classification for literature that attempts to mimic the real world. Fiction that seeks verisimilitude.

The narrative representation of events by compressing their duration.

The narrative representation of an environment, set of characters, and sequence of events in enough detail to create the illusion that the events are unfolding in front of the narratee (and ultimately, the reader).

Use of discourse to state something different from, or even opposite to, what is meant.

A narrator who makes statements about the characters or events in the story that mean something very different, even the opposite, of what is being stated.

A narrator who makes statements that contradict what the implied reader knows (or infers) to be the real intention or meaning of the narrative discourse.

Similar to parody and caricature, a genre of fiction or a specific tone/mood in narrative that lampoons the status quo or powerful societal interests or people.