6 – Language

Image by mohamed_hassan on Pixabay, adapted by Ben Storey.

Image by mohamed_hassan on Pixabay, adapted by Ben Storey.

6.1 Defining Language

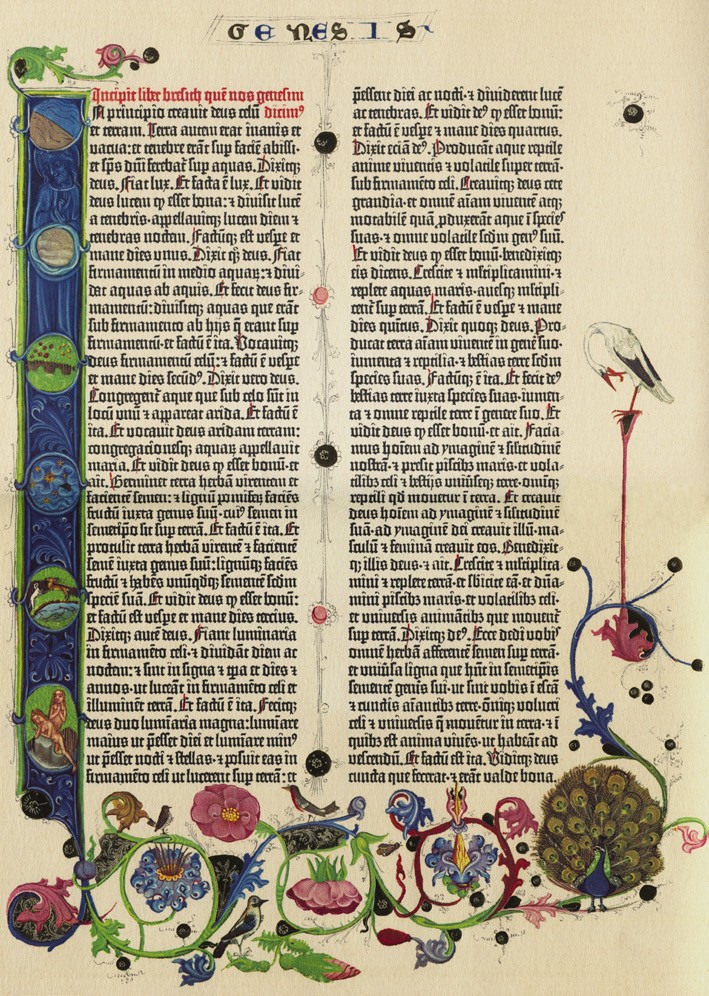

Fig.6.1 First page of the Book of Genesis in the Gutenberg Bible, Public Domain, https://de.wikipedia.org/ wiki/Gutenberg-Bibel#/media/File:Gutenberg_Bible_B42_Genesis.JPG

When we speak about literature, there is no doubt that narrative discourse is made up of language. In fact, the closest we can get to a definition of literature might be to say that it is “the creative use of language.”1 Of course, not all stories are told using language. We have already seen (in Chapter 1) that stories can be expressed in many different media, such as comics, dance, radio drama, video games, or movies. By definition, however, prose fiction narratives are precisely those where a narrator tells a story using words arranged into sentences (see Fig. 6.1).

The language employed in prose fiction varies widely. Some stories are told in a language that seems common or ordinary, with little use of adjectives and figurative devices, as in Raymond Carver’s “Cathedral” and other minimalist short stories. Carver, Tobias Wolff, and Charles Bukowski, among others, are sometimes called the “dirty realists,”2 for their focus on the mundane aspects of life through plain, unadorned language. At the other extreme, some stories are written in a style that is so far removed from everyday language that most readers have a hard time understanding it, as in James Joyce’s experimental novel Finnegans Wake. This diversity of styles and techniques makes it difficult to describe the language of narrative in any systematic way, short of saying that it is a reflection of the variability of language itself.

Ben’s Bonus Bit – Hemingway vs. Faulkner

The two most important stylists of the 20th century were both modernists and Nobel Prize winners: William Faulkner (1949) and Ernest Hemingway (1954). Hemingway, who began his writing career as a journalist for the Kansas City Star popularized an objective, terse prose style that came to dominate the instruction of writing. Affecting a journalistic stance, Hemingway stripped sentences of most adjectives, adverbs, clunky punctuation, and “telling” exposition. As the Nobel Committee noted, Hemingway’s “forceful and style-making mastery of the art of modern narration” contributed to an American modernism that finally flung off British affectations and sentimentality.

In his stories and novels, the burden of meaning-making falls heavily to Hemingway’s dialogue, where repetition and subtext reveal theme. About a writer’s style, Hemingway wrote that it “should be direct and personal, his imagery rich and earthy, and his words simple and vigorous.” In Death in the Afternoon, Hemingway tells us, “If a writer of prose knows enough of what he is writing about, he may omit things that he knows, and the reader, if the writer is writing truly enough, will have a feeling of those things as strongly as though the writer had stated them. The dignity of movement of an ice-berg is due to only one-eighth of it being above water.”3 This choice in prose style has come to be known as the Iceberg Theory, that the meaning of a story should not be visible on its surface.

About Hemingway, Faulkner, who is famous for dense sentences, long paragraphs, impressive vocabulary, and stream of consciousness narration, said, “He has no courage, has never crawled out on a limb. He has never been known to use a word that might cause the reader to check with a dictionary to see if it is properly used.”4 Not one to skip a feud, the churlish Hemingway responded, “Poor Faulkner. Does he really think big emotions come from big words? He thinks I don’t know the ten-dollar words. I know them all right. But there are older and simpler and better words, and those are the ones I use.”5 Modern writers exist in both stylistic traditions. Besides the dirty realists, as mentioned above, the excellent Japanese writer Haruki Murakami and PEN/Malamude winner Ann Beattie mark Hemingway as a principle influence. Toni Morrison, Flannery O’Connor, Alice Munro, Mo Yan (Nobel Prize 2012), Gabriel Garcia Marquez, and many others cite Faulkner as inspiration. Some writers, such as Cormac McCarthy, may even belong to both camps, bridging what once seemed an impossible stylistic divide.

For students of literature, what matters is your capacity to identify and articulate differences in prose style: sentence length, complexity of diction, use of elaborate metaphor or grounded description, prose rhythm, use and effect of punctuation, sentence structure (periodic vs. running), frequency of adjectives/adverbs, how language impacts tone, etc. Learn the vocabulary scholars use to describe difference in prose style to add credibility (ethos) to your textual analyses. Avoid the vague and cliched term “flow,” which student writers so often lean on to describe prose rhythm or pacing. Rappers have flow. Rhyme-heavy poets perhaps have flow. People playing Tetris definitely enter a “flow state.”6 Analysis of prose fiction needs more precise language.

The study of language in literature and other forms of discourse has traditionally been the task of rhetoric, an ancient discipline that attempts to understand and teach the art of crafting effective and persuasive discourse. The tradition of rhetoric still influences the analysis and classification of figures of speech and other linguistic devices employed in contemporary prose fiction. In recent times, modern linguistics applied to the study of literary texts has given rise to stylistics, a discipline that maintains some of the interests and terminology of traditional rhetoric, while incorporating new concerns, concepts, and methodologies.

In this chapter, we will present some key insights about the language of short stories and novels, mostly derived from rhetoric and stylistics, without burdening readers with the linguistic details. To begin, we need to explain what we mean by style, a characteristic set of linguistic features that is sometimes attributed to the implied author of a story, but also to the real author, or even to a group of authors or to a whole culture. Then, we will discuss the notion of foregrounding, which can help us to identify with more precision the features that distinguish literary from everyday language. Foregrounding in prose fiction can involve different aspects of language, such as the use of figurative devices or figures of speech. After reviewing the most significant of these devices for narrative prose, we will examine the use of symbols and allegory in short stories and novels, an aspect of discourse that brings together language and theme. We will end the chapter by briefly pointing out the importance of literary translation in giving readers access to the rich variety of prose fiction stories written all over the world.

6.2 The Style of Narrative

In our semiotic model of narrative, discourse is the message that the implied author communicates to the implied reader. This message not only has a content, which is the story, but also a form. The form of discourse is what we generally call its style. In general, the style is a characteristic set of linguistic features associated with a text or group of texts. Thus, the style of a short story or novel is the sum of linguistic features that characterize its narrative discourse.

Narrative style may be attributed to the implied author, which is the virtual entity who enounces the discourse. In this sense, it is generally possible to analyze the linguistic features of style based on the text itself, without any need to know the identity of its real author. In some cases, as in anonymous works or publications under a pseudonym, we might not even have this information. However, we can still identify the specific linguistic features of the text that define its style, or more precisely the style of its implied author. It is in this way that we speak, for example, of the style of One Thousand and One Nights, even though it is probably the work of several anonymous compilers.

When we know the identity of the real author of several narratives, we might compare the linguistic features of these works and identify a common style that can be attributed to that author. For example, we speak of the writing style of Jack Kerouac by comparing the style of novels like On the Road or The Dharma Bums. Sometimes, we can also identify linguistic features that are shared by texts written in the same genre, or around the same time, or in the same geographic or cultural area, even when the authors are different. In these cases, we may attribute a certain style to a genre (e.g. the style of thrillers), a period (e.g. the style of Romantic novels), or a whole culture (e.g. the style of Korean literature).

Ben’s Bonus Bit – The Dangers of Over-generalization

This last category (cultural commentary) is tricky, and readers who do not belong to the culture under study should be careful not to overgeneralize while writing essays. If, in the study of Flannery O’Connor, for instance, we describe Southern Literature of the 20th century as “fundamentally gothic,” several prominent southern literary critics and writers will take issue. What of Margaret Mitchell, Zora Neale Hurston, or John Kennedy Toole?7 What of Ralph Ellison (born in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma) or Richard Wright (Moxie, Mississippi)? Should they be forgotten or not considered “southern”? Novice scholars should take care when making sweeping claims about groups of people, places, or time periods. Poor essays often begin with clumsy rhetorical missteps. Begin making over-broad claims about the Harlem Renaissance or Korean Literature or the Latin American Magical Realists, and readers will see generalization as stereotyping.

Similarly, beware phrases like “it is obvious that” or “it is evident that,” which often precede over-generalizations. Two outcomes are possible: 1) if the subsequent claim actually is obvious and true, readers will wonder why the writer has included it in the essay, which should, by definition, try to advance knowledge. If a claim is genuinely evident, it need not be said. 2) more likely the novice writer has used the phrase as a kind of verbal deterrent to avoid criticism or objection. If the claim isn’t obvious and is in fact debatable, readers may see the line as short-circuiting or bypassing a productive interpretive debate/discussion. Yes, essays at the collegiate level should be ambitious and make bold claims, but authors must be aware of their potentially limited education on historical periods, different cultures, or literary movements. When in doubt, quote literary critics and scholars, borrowing their ethos for pronouncements about Magical Realism or the Southern Gothic.

Given that short stories and novels are products of modern culture, which gives considerable importance to originality and to the creative genius of authors, it is not surprising that style should be associated most often with the identity and reputation of a given writer. In such a context, writers themselves often strive to shape (or find) their own style—a unique and identifiable set of linguistic features that can raise the literary value of their work.

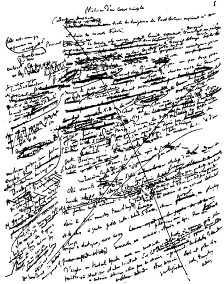

But style is not just the result of search for literary glory. Authors, as a whole, are conscious of their use of language, being aware of the crucial importance of choosing the right word, the right turn of phrase to engage the interest and imagination of their readers. Gustave Flaubert, for example, was famously determined to write in the most perfect style, searching for “le mot juste,” working tirelessly to craft every sentence, every paragraph, sometimes for weeks or months. And although he published some of the most elegant and evocative short stories and novels in the history of literature, with a prose style that has been admired ever since, he always labored under the impression that his daily battle for perfection could not be won (Fig. 6.2). “Human language,” says the narrator of Madame Bovary, “is like a cracked pot on which we tap crude melodies to make bears dance, while we long to melt the stars.”8

Fig. 6.2 Facsimile of the first draft of Gustave Flaubert’s short story ‘A Simple Heart’ (Paris: Edition Conard des Oeuvres Complètes, 1910), Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/ File:Gustave_Flaubert_-_Trois_Contes,_page_66.jpg

6.3 Foregrounding

As mentioned above, style is the set of linguistic features that characterize a text. Thus, style generally results from multiple, complex decisions about rhythm, phonological patterns, syntactic structure, lexical choice, collocation, paragraph organization, etc. These decisions are guided by habit and convention. But they can also involve deliberate deviance from established norms and standards. In literature, these deviations are generally more frequent and significant than in other forms of discourse.

A key aspect of literary style is thus foregrounding. If the language that we use to communicate in everyday situations is taken as the ‘norm,’ there are many literary texts, including short stories and novels, which deviate from that norm for effect. Of the specific linguistic features in those texts that diverge from the normal use of language, or from the background, we say that they are foregrounded. For example, if we wanted to describe the presence of bees in a garden where two people are sitting in silence, we could say something like, “The silence was interrupted by the buzzing of bees around the plants.” There is nothing extraordinary in this sentence, which simply tries to convey the intended meaning as economically as possible. The narrator of Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray, however, expresses the same idea differently: “The sullen murmur of the bees shouldering their way through the long unmown grass, or circling with monotonous insistence round the dusty gilt horns of the straggling woodbine, seemed to make the stillness more oppressive.”9 In this long, resonant sentence, which uses many adjectives and figures of speech, the language is foregrounded and brought to the attention of the reader.10

The degree of foregrounding in literary texts varies considerably. In lyrical poetry, for example, language is usually much more foregrounded than in prose narrative. Short stories and novels, especially the most popular ones, are often written in a style that exhibits few or no perceptible differences from everyday language, even if dialogue is cleaned of its hitches, false starts, fillers, and small talk or if inner monologue is organized for coherency. But there are also many pieces of prose fiction whose language deviates as much as any poem from a supposed norm. Gertrude Stein, for example, is famous for her experimental, droning stories (and poems) that aim to separate words from socially-constructed meaning.11 Stein writes, “A rose is a rose is a rose,” and readers, presumably, consider different meanings with each iteration of the word. Short stories and novels written in prose that uses a highly foregrounded language, reminiscent of lyrical poetry, are sometimes classified as poetic or lyrical prose. Consider, for example, this paragraph from Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse:

To want and not to have, sent all up her body a hardness, a hollowness, a strain. And then to want and not to have — to want and want — how that wrung the heart, and wrung it again and again!12

While foregrounding can be a useful notion to analyze the style of literary texts, it is increasingly difficult to sustain the idea that there is a style-free norm that could serve as background or as a reference to identify the features of aberrant or unusual literary style. Even when we communicate with each other in everyday situations, our language is not devoid of figures of speech and other linguistic devices that we associate with literary language (note, for example, the alliteration in the ‘buzzing of bees’ of the sentence above). This is particularly the case for metaphors, which are the most significant and widely used figure of speech. Metaphors are commonly employed in prose fiction, but they are also found in ordinary conversation and constitute the most important source of new words and expressions in any language.13

Moreover, we should not forget that foregrounding is not just a way of calling attention to language itself, but can serve important functions in narrative and other forms of discourse. In prose fiction, foregrounded language is commonly used in descriptions, when representing characters or environments and when summarizing events. In most ordinary communication, both the speaker and the listener share a context to which they can refer explicitly or implicitly—a shared sense of place, work culture, or relational history. In principle, the narrator could also rely on a shared context when telling the story to the narratee. But then many of the details and meanings of the story would be lost to implied readers, who have no presence at the level of discourse and no direct access to the storyworld. In fact, the existents of the storyworld (events, environments, and characters) only exist insofar as narrative discourse succeeds in representing them in the imaginations of readers. And this can only be done by means of language. In narrative communication, therefore, language is burdened, not only with conveying meaning, but also with recreating the whole context where meaning can emerge in readers’ minds.

To succeed in this difficult task, literary discourse needs to use the features of language in slightly different ways than normal discourse. For example, descriptions in prose fiction often include nouns, adjectives, and phrases that evoke sensory experiences and convey significant details to readers. In summaries and scenes, verbs and adverbs are often carefully selected to recount as precisely and meaningfully as possible the actions of characters and other events in the plot. Moreover, sentences are crafted, not just to communicate events and ideas, but also to affect the rhythm and pace of the narrative. But perhaps the most noticeable rhetorical aspect of literary discourse, common to both short stories and novels, is the widespread use of figurative language to stimulate and engage the reader’s imagination.

6.4 Figures of Speech

Figurative language, which includes rhetorical figures, tropes, and figures of speech, is the use of language in ways that deviate from the literal meaning of words and sentences. Literal meaning refers to the definition or denotation of words. Figurative meaning, on the other hand, exploits the connotations and associations of words with other words or sounds.

This definition covers an array of linguistic features, most of which are part of everyday language, given that we seldom rely exclusively on literal definitions when we communicate. The difference between literary and ordinary language is not that one uses figures of speech while the other one does not. Both literary and ordinary discourse use figurative language, but in literature its use tends to be controlled, sustained, and creative.

Throughout history, there have been many classifications of figurative devices, which can be found in treatises and textbooks on rhetoric.14 Here, we will only introduce briefly the most common figures of speech found in narrative discourse, giving some examples drawn from short stories and novels:

- Metaphor: a metaphor establishes a relationship of resemblance between two ideas or things by equating or replacing one (the ‘tenor’) by the other (the ‘vehicle’). Metaphors are usually not created from similarity in denotation (literal meaning) but from some similarity in the connotation of words (their associated or secondary meanings). In Kate Chopin’s short story “The Storm,” for example, the narrator describes the sexual encounter between Alcée and Calixta by saying, “Her mouth was a fountain of delight.” Of course, she does not mean that there was delight, much less any kind of liquid, gushing from Calixta’s mouth. But the image created by the narrator’s metaphor, equating the woman’s mouth (tenor) to a fountain (vehicle), allows the reader to understand more vividly the cascade of emotions experienced by Alcée as he kisses his lover. Metaphor is perhaps the most important figure of speech, and many other forms of figurative language can be considered, in a broad sense, metaphorical.

- Simile: Like metaphor, a simile establishes a relationship of resemblance between two ideas or things (tenor and vehicle), but it makes the comparison explicit with a connector (usually, ‘like’ or ‘as’). This connector is not a mere linguistic conjunction, but it allows the simile to specify more clearly the quality or attribute that underlies the comparison between tenor and vehicle. In John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath, for example, the narrator describes the landscape with the following words, “The full green hills are round and soft as breasts.” Here, the hills (tenor) and the breasts (vehicle) are explicitly compared in terms of certain connotative qualities (roundness and softness), but not others (e.g. greenness).

- Personification: personification attributes personal or human characteristics to a nonhuman entity, object, or idea. In this case, the tenor is not human while the implicit or explicit vehicle is a human-specific quality or attribute. A variant of personification is the attribution of characteristics of animate entities, such as nonhuman animals, to inanimate objects or ideas. In Arundhati Roy’s The God of Small Things, for example, the narrator describes a house (tenor) as if it were an awkwardly dressed person (vehicle): “The old house on the hill wore its steep, gabled roof pulled over its ears like a low hat.”

- Metonymy: metonymy replaces an idea or thing by another idea or thing with which it is somehow connected or related in meaning. Unlike metaphor, metonymy does not transfer qualities or attributes from the vehicle to the tenor. In a metonymy, ideas or things are associated because of their contiguity, not their resemblance. The narrator of Louis-Ferdinand Céline’s Journey to the End of the Night, for example, says: “When you write, you should put your skin on the table.” Here, the skin is not replacing the writer’s self or consciousness based on any resemblance but because it is contiguous or envelops his body.

- Synecdoche: synecdoche is a form of metonymy (or at least, closely related) where a part refers to the whole of something, or vice versa. In Margaret Mitchell’s Gone with the Wind, one of the characters says, “I’m mighty glad Georgia waited till after Christmas before it secedes or it would have ruined the Christmas parties.” The whole state of Georgia refers to its constituents, or rather to its government and legislators. This synecdoche is common, as we often speak of the actions of a country’s government as if they were taken by the whole country.

- Hyperbole: hyperbole is an exaggeration aimed at emphasizing a certain point or creating a strong impression. In Gabriel García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude, for example, the narrator introduces the imaginary and primeval world of Macondo with this hyperbolic description: “The world was so recent that many things lacked names, and in order to indicate them it was necessary to point.”

- Oxymoron: oxymoron connects or combines elements that appear contradictory but in fact contain a concealed connection or a paradox. The narrator of David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest, for example, makes this paradoxical statement: “That everybody is identical in their secret unspoken belief that way deep down they are different from everyone else.”

Tropes are routinely used in everyday language, even if they often are not perceived as figures of speech by speakers or listeners. When a figure of speech has been incorporated into normal language and is no longer recognized, we say that it is dead (which is itself personification). For example, to say that one has “fallen in love” (dead metaphor) or that “time is running out” (dead personification) no longer elicits the kind of surprise, sensory experience, or revelation that figures of speech are supposed to elicit. However, dead tropes still convey some of their figurative meanings and associations. In general, dead tropes tend to be successful metaphors, and this is why they have become so much a part of common language that we do not even notice them anymore.

Other tropes that are also used quite often, both in everyday language and in literary discourse, are clichés. Unlike dead figures of speech, clichés often fail to convey a figurative meaning or create any sensory effect for readers. Instead, they call attention to themselves, coming across as commonplace and annoying. Examples of clichés are similes such as “eyes like stars” or “teeth like pearls,” which have been so overused in the Western literary tradition that they have lost much of their original force. It is usual, therefore, for critics and rhetoricians to recommend aspiring writers to avoid clichés as much as possible. Clichés may exist in Young Adult fiction or children’s fiction unironically, but writers of literary fiction aspire to avoid them.

In other cases, writers go too far in their efforts to coin new and original tropes and fall into the opposite stylistic blunder. Farfetched tropes or conceits are figures of speech that are too strange, complex, awkward, or extreme to be effective. Like clichés, they call attention to themselves in a negative way. Comparing eyes to “pearly teeth,” for example, seems a farfetched image, a conceit that would probably leave readers baffled. In what ways are eyes like teeth? We do have “hungry eyes” occasionally. Eyes do have an off-white color in their conjunctiva cells. This reaching for comparison is too much work for readers.

In figurative language, however, as in all matters of style, there are no hard rules or universally valid prescriptions. Readers and critics must decide whether a trope, no matter how trite or farfetched it may seem, is effective in the context of a particular narrative discourse.

6.5 Symbolism

In general, a symbol is anything that represents something else by virtue of an arbitrary association.15 Symbols commonly used by modern humans are traffic signs, words, and flags, among many others. Symbols might represent other objects or things, but they can also represent individuals or groups of people, cultures, ideas, beliefs, values, etc. Human language is a symbolic system, and we routinely use non-linguistic symbolic systems. There is no doubt that symbols play a crucial role in our understanding of the world and allow us to communicate effectively with each other. This textbook is rooted in semiotics, the study of signs and symbols.

In narrative discourse, any existent of the story (event, environment, or character) can become a symbol. Sometimes, symbolic associations are expressed by the narrator or by characters in the story, but they can also be left implicit. Some symbols are unequivocally associated with a certain meaning, like the letter ‘A’ that adulterous women are forced to wear to symbolize their crime in Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter. But there are other symbols whose meaning is open to interpretation, like the ‘night’ in Elie Wiesel’s novel Night, which could be understood to represent, amongst other things, death, Nazism, despair, the loss of faith, or the Holocaust.

Some symbols used in narrative carry their meaning directly from the lifeworld of writers and readers, such as the Christian symbol of the cross. But narratives can also create new symbols, by associating existents of the story with any arbitrary meaning, or give new meanings to symbols that are also used in the lifeworld of readers. For example, the father and son in Cormac McCarthy’s bleak novel The Road speak about having or carrying “the fire,” which they conceive as a symbol of goodness and hope as they try to survive post apocalypse.

Narrative symbols can be internal, when they are associated with other existents of the story. In the Harry Potter series, for example, the scar on Harry’s forehead symbolizes the connection with his mortal enemy Lord Voldemort but also marks him as the hero chosen to defeat the evil forces. Symbols can also be external, when the referent is not part of the storyworld but belongs to the level of discourse or the lifeworld of readers. Again, in Harry Potter, the names of some characters, like Albus Dumbledore, are symbolic to the extent that they refer to meanings in Latin (“albus” means white) or Old English (“dumbledore” means bumblebee), which are only relevant for the implied (or real) reader.

In certain narratives, symbolism becomes the structuring framework of the whole story, turning the events, environments, and characters of the storyworld into representations of something other than themselves, generally moral or abstract ideas. This is what we call an allegory, from the Ancient Greek “to speak of something else.” Religious myths, like the story of Christ’s crucifixion or the life of Buddha, are often constructed as allegories. Beyond their literal meaning, they have a moral and metaphysical significance.

Sometimes, readers will interpret a story as an allegory even if the author did not intend to write it as such. This is called allegoresis, the act of reading any story as allegory. But there are also short stories and novels that are meant to be read as allegories. Narrative discourse is then constructed in such a way that invites readers to find hidden or transcendent meanings in the events, characters, or environments of the storyworld. This kind of sustained symbolism is quite common in fables, parables, and other literary stories that attempt to convey a lesson or illustrate a complex or abstract idea in narrative form. The invisible man’s journey from the rural South to the urban North in Ellison’s Invisible Man may be read as an allegory of the Great Migration, a key 20th century event (1916-70) when nearly 6 million African Americans sought to escape economic despair and segregationist Jim Crow laws.

Fig. 6.3 A depiction of a pig dressed as a human capitalist to illustrate George Orwell’s Animal Farm. By Carl Glover, CC BY 2.0, https://www.flickr.com/ photos/34239598@N00/16143409811

An example of modern political allegory is George Orwell’s Animal Farm, a novel about farm animals rebelling against their human owners (Fig. 6.3). While the story can be read literally as a sort of fairytale, the events, characters, and environments of Orwell’s imaginary storyworld clearly stand in for the real events, characters, and environments of the Russian Revolution. Orwell extracts a moral and political lesson about the degeneration of Communist ideals into outright tyranny.

6.6 Translation

Prose fiction is written in hundreds of different languages throughout the world. Languages that have the largest share of total speakers (and therefore, writers and readers) tend to be also the languages in which most books are published, although the correlation is far from exact. At the top of the list, we find languages like English, Chinese, Spanish, French, German, Japanese, and Russian. But there are many other languages with a relatively small number of speakers and yet a considerable number of readers and writers, such as Norwegian, Catalan, or Czech. And there are also widely spoken languages like Malay, Swahili, or Punjabi, whose proportion of writers and publications is comparatively small, but still adds up to a large number in absolute terms.

In such a diverse and globalized world, no reader could possibly read every story in its original language. Even someone with proficiency in all major languages of the planet would require at some point or another to rely on translation to read prose fiction written in relatively minor or distant languages. Thus, translations play a crucial role in allowing the flow of ideas and stories across different cultures.16 How many people in China or Japan, for example, have read the original Pride and Prejudice or Don Quixote? And how many Europeans have read, or would be able to read, the original Romance of the Three Kingdoms, Dream of the Red Chamber, or the Tale of Genji? In fact, how many practicing Christians around the world have read the Old Testament of the Bible in its original Hebrew?

But a translation is far from being an exact reproduction of the original text. Like adaptations, literary translations are always interpretations or rewritings of the original. Even if the translator is successful in faithfully preserving the existents of the story, its narrative discourse is going to be different because it is written in another language. When translating prose fiction, translators need to make difficult linguistic and interpretative choices, balancing their fidelity to the original content and form with the specific requirements and possibilities of the target language. They also need to take into account the expectations of readers in a different language, as well as the rules and conventions prevalent in that culture.

Perhaps the most formidable challenge of literary translation is how to reproduce the style of the original text in the target language. This difficulty tends to increase with the degree of foregrounding of the linguistic features of the text. Thus, translating a popular thriller, such as Dan Brown’s The Da Vinci Code, into hundreds of languages is a simple operation, which does not require difficult decisions on the part of various translators. On the other hand, translating a lyrical and highly elliptical short story like Yasunari Kawabata’s “The Dancing Girl of Izu,” or a polyphonic modernist novel like Alfred Döblin’s Berlin Alexanderplatz, with its heavy use of slang and local dialect, can be a daunting task for any translator. This is also the reason why, in general, the translation of poetry tends to be more difficult, and its results more uncertain, than the translation of prose fiction.

In short, literary translation is a creative endeavor, and one that is often unrecognized and undervalued, despite its obvious cultural benefits. While reading a translation is never the same as reading the original, it is the only means for most readers to access the rich and boundless variety of stories that make up ‘world literature.’17

6.7 Summary

- Style is the characteristic set of linguistic features (rhythm, phonology, syntactic structure, lexical choice, etc.) associated with a text. Style can be attributed to the implied author, but also to the real author, and even to a specific cultural group

- A key aspect of literary style is foregrounding. To effectively communicate the content and meaning of the story and engage the imagination of readers, narrative discourse often relies on foregrounded language, deploying features and devices that diverge from normal or everyday language

- Figurative language, or the use of figures of speech, including metaphor, simile, personification, metonymy, synecdoche, hyperbole, oxymoron, and others, is a common form of foregrounding in prose fiction

- Events, environments, and characters in prose fiction become symbols when they represent something other than themselves by virtue of an arbitrary association. When symbolism is sustained throughout the narrative, the story becomes an allegory, and

- Despite its complications and limitations, translation is the only means by which most readers can access the rich diversity of short stories and novels published throughout the world.

Licenses and Attributions:

CC licensed content, Shared previously:

Ignasi Ribó, Prose Fiction: An Introduction to the Semiotics of Narrative. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2019. https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0187

Version History: Created new verso art. Added quick links. Bolded keywords. Made minor phrasing edits for American audiences. Adopted MLA style for punctuation. Changed paragraphing for PressBooks adaptation. Moved footnotes to endnotes. Added references to “le mot juste,” Gertrude Stein, Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man, and Dream of the Red Chamber. Included young adult and children’s literature as genres that play in clichés. Added vocabulary: dirty realism. Included “Ben’s Bonus Bits,” with a host of new vocabulary, October, 2021.

Linked bolded keywords to Glossary and improved Alt-image text for accessibility, July, 2022.

End Notes

- Geoffrey N. Leech, Language in Literature: Style and Foregrounding (Harlow, UK: Pearson Longman, 2008), p. 12, https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315846125

- See Bill Buford in the 1983 Summer edition of Granta magazine.

- See Ernest Hemingway (1990). “The Art of the Short Story”. In Benson, Jackson (ed.). New Critical Approaches to the Short Stories of Ernest Hemingway. Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-1067-9.

- See Faulkner’s transcribed words to a creative writing class in the Summer 1951 issue of the quarterly The Western Review.

- See the chapter “Havana 1951-53” in A. E. Hotchner’s Papa Hemingway: A Personal Memoir (1966).

- See Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly. Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. New York: Harper & Row, 1990. There are excellent TED talks and YouTube videos on the subject.

- See Bryant, J. A., Jr. Twentieth-Century Southern Literature. The University Press of Kentucky, 2015. Project MUSE muse.jhu.edu/book/37269.

- Gustave Flaubert, Madame Bovary: Provincial Manners, trans. by Margaret Mauldon and Mark Overstall (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2004), p. 170.

- Oscar Wilde, The Picture of Dorian Gray, ed. by Robert Mighall (London, UK: Penguin, 2003), p. 5.

- See also Roman Jakobson, ‘Linguistics and Poetics’, in Style in Language (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1960), pp. 350–77, where foregrounding is described in terms of the ‘poetic function’ of linguistic communication.

- See Stein, Gertrude, and Natalie C. Barney. As Fine As Melanctha, 1914-1930. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1954.

- Virginia Woolf, To the Lighthouse, ed. by Max Bollinger (London, UK: Urban Romantics, 2012), p. 135.

- George Lakoff and Mark Johnson, Metaphors We Live By (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2017).

- For example, Ward Farnsworth, Farnsworth’s Classical English Rhetoric (Jaffrey, NH: David R Godine, 2016).

- Charles Sanders Peirce, Philosophical Writing of Peirce, ed. by Justus Buchler (New York, NY: Dover Publications, 1955), pp. 102–3.

- Susan Bassnett and André Lefevere, Constructing Cultures: Essays on Literary Translation (Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters, 1998), pp. 9–10.

- Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Conversations with Eckermann, trans. by John Oxenford (New York, NY: North Point Press, 1994), p. 132.

References

Bassnett, Susan, and André Lefevere. Constructing Cultures: Essays on Literary Translation (Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters, 1998).

Bryant, J. A., Jr. Twentieth-Century Southern Literature. The University Press of Kentucky, 2015. Project MUSE muse.jhu.edu/book/37269.

Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly. Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. New York: Harper & Row, 1990. Print.

Farnsworth, Ward. Farnsworth’s Classical English Rhetoric (Jaffrey, NH: David R Godine, 2016).

Flaubert, Gustave. Madame Bovary: Provincial Manners, trans. by Margaret Mauldon and Mark Overstall (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2004).

Goethe, Johann Wolfgang von. Conversations with Eckermann, trans. by John Oxenford (New York, NY: North Point Press, 1994).

Hemingway, Ernest. “The Art of the Short Story”. In Benson, Jackson (ed.). New Critical Approaches to the Short Stories of Ernest Hemingway. Duke University Press. 1990.

Hotchner, A E. Papa Hemingway: A Personal Memoir. New York: Random House, 1966. Print.

Jakobson, Roman. “Linguistics and Poetics,” in Style in Language (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1960), pp. 350–77.

Lakoff, George, and Mark Johnson. Metaphors We Live By (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2017).

Leech, Geoffrey N. Language in Literature: Style and Foregrounding (Harlow, UK: Pearson Longman, 2008).

Peirce, Charles Sanders. Philosophical Writing of Peirce, ed. by Justus Buchler (New York, NY: Dover Publications, 1955).

Stein, Gertrude, and Natalie C. Barney. As Fine As Melanctha, 1914-1930. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1954.

Wilde, Oscar. The Picture of Dorian Gray, ed. by Robert Mighall (London, UK: Penguin, 2003).

Woolf, Virginia. To the Lighthouse, ed. by Max Bollinger (London, UK: Urban Romantics, 2012).

Visually descriptive or figurative language. Despite its association with vision, auditory, tactile, or olfactory imagery also exists but may sometimes be labeled sensory detail.

The art of crafting effective or persuasive discourse.

A characteristic set of linguistic features associated with a text or group of texts.

A set of linguistic features of discourse that deviate from the normal or ordinary use of language.

The use of language in ways that deviate from the literal meaning of words and sentences, exploiting connotations and associations with other words or sounds. (See also Figurative Language, Rhetorical Device, Trope.)

Anything that represents something else by virtue of an arbitrary association. In narrative, symbols are existents of the story that become arbitrarily associated with internal or external meanings.

A story that uses extended symbolism in order to communicate meanings, generally moral or abstract ideas, beyond the literal meaning of events, environments, and characters.

The means through which a narrative is communicated by the implied author to the implied reader.

Conventional grouping of texts (or other semiotic representations) based on certain shared features.

Representation of verbal or speech interactions between characters, often accompanied by dialogue or speech tags.

A figure of speech that establishes a relationship of resemblance between two ideas or things by equating or replacing one with the other.

The textual representation of characters or environments.

A descriptive detail that reveals meaningful connections between the existents of the story and helps the reader to recreate the storyworld in her imagination.

The narrative representation of events by compressing their duration.

The narrative representation of an environment, set of characters, and sequence of events in enough detail to create the illusion that the events are unfolding in front of the narratee (and ultimately, the reader).

The use of language in ways that deviate from the literal meaning of words and sentences, exploiting connotations and associations with other words or sounds. (See also Figure of Speech.)

The use of language in ways that deviate from the literal meaning of words and sentences, exploiting connotations and associations with other words or sounds. (See also Figure of Speech.)

A figure of speech that establishes a relationship of resemblance between two ideas or things through an explicit comparison using a connector (usually, ‘like’ or ‘as’).

A figure of speech that attributes personal or human characteristics to a nonhuman entity, object, or idea.

A figure of speech that replaces an idea or thing with another idea or thing, with which it is somehow connected or related in meaning.

A figure of speech, closely related with metonymy, where a term for a part refers to the whole of something, or vice versa.

A figure of speech that makes an exaggerated claim to emphasize a point or create an impression.

A figure of speech that connects or combines elements that appear to be contradictory, but which contain a concealed point or a paradox.

The use of language in ways that deviate from the literal meaning of words and sentences, exploiting connotations and associations with other words or sounds. (See also Figure of Speech.)

A figure of speech that has been incorporated into normal language and is no longer recognized as such.

A figure of speech that has been so overused that it has lost much of its original force and is perceived in negative terms.

A figure of speech that seems too strange, complex, awkward, or extreme to be effective, and tends to call attention to itself, often in a negative way. (See also Farfetched Trope.)

A change of state occurring in the storyworld, including actions undertaken by characters and anything that happens to a character or its environment. Also called a “plot point.”

Everything that surrounds the characters in the storyworld.

An entity with agency in a storyworld.

The inclusion in narrative of a diversity of points of view and voices.