A Critique of Cowspiracy: The Sustainability Secret

Nicholas Blundell

The world is in peril. Anthropological climate change is ravaging the globe. Record droughts, hurricanes, and ocean acidification are all occurring at untold levels. The only way to reverse these effects is if every person on the planet switches to a plant-only diet that uses no animal input whatsoever to grow – at least according to Kip Andersen. Andersen is the producer and writer of Cowspiracy: The Sustainability Secret. For those unfamiliar, the film is a documentary investigating agriculture’s effects on the climate. Through interviews with the heads of environmental advocacy groups, journalists, animal rights activists, and others, Andersen aims to uncover why the rest of the world is not concerned with the damage agriculture contributes to climate change. His film indicts agriculture and farming as the leading cause of greenhouse gas emissions, accounting for a staggering 51% of the global emissions. This statistic is the backbone for the film, deriving from a Worldwatch Institute climate change report stating just that (Andersen, Keegan, 2014). Andersen’s thesis is that environmental groups are, on average, part of a conspiracy to ignore or protect the agriculture industry, hence the name Cowspiracy.

“Cowspiracy aims to uncover the veil put over the public’s eyes on the subjects of agriculture and climate change, but it has a problem… Through deceptive cinematography tricks and the use of unreliable statistics, the documentary presents an overly biased view on the topic that does more harm than help.”The documentary itself is easy on the eyes and an overall fun watch. Cowspiracy contains numerous easy-to-read visuals and infographics peppered throughout the documentary that, at surface level, are very informative. The cinematography in many shots and camera angles induce the feeling of a true investigative journalism report, such as secretive filming scenes used to uncover the truth. Major highlights of the film include numerous interviews with environmental advocacy groups and other climate activists, “what-if” scenarios that flesh out the implications of making all farming and fishing sustainable, and the journeys Andersen undertook to uncover the truth behind agriculture’s impact on the globe. Cowspiracy aims to uncover the veil put over the public’s eyes on the subjects of agriculture and climate change, but it has a problem. By doing so, it installs its own veil on the viewer. Through deceptive cinematography tricks and the use of unreliable statistics, the documentary presents an overly biased view on the topic that does more harm than help.

Synopsis

The documentary opens with a startling statistic presented by the director of the Sierra Club, in which the world is facing unparalleled danger due to CO2 emissions. Andersen asks about animal agriculture, sparking an abrupt cut in ominous music and a response: “Well, what about it?” (Andersen et al, 2014, 0:1:51). After setting the basis for the documentary, the film introduces the director and protagonist: Kip Andersen. It details his normal American upbringing to his self-described obsessive-compulsive environmentalism and all the sustainable activities he lives by. This scene then transitions to his discovery of the backbone statistic for the documentary: a UN report stating that agriculture accounts for 51% of all greenhouse gas emissions. This precipitates Andersen’s thesis, which is that agriculture is responsible for the majority of greenhouse gas emissions and environmental degradation, and he is determined to discover why no one else is talking about it. Andersen researches the leading environmental advocacy groups, including Greenpeace, Sierra Club, Oceana, and Surfrider. Anderson interviews the local government and other climate activists in order to understand why no one is concerned with agriculture’s impact. He follows up by interviewing the heads of each of the advocacy groups with the same question, excepting Greenpeace. The final interview with Oceana cues a segment on the detriments of over-fishing the oceans.

After describing the detriments of fishing, Andersen switches his focus to deforestation and agricultural waste, prompting several interviews with rainforest protection groups. An answer he finds in the interviews is the idea of free-range agriculture, sending Andersen to one such farm to another interview, who were a small family of ranchers. Post-interview, Andersen does some quick calculations to estimate the demand for switching to entirely grass-fed beef. His conclusion is that grass-fed beef is even more unsustainable than factory farming. He continues with more interviews of factory farm owners, ranchers, and to show how damaging farming and ranching is. He then interviews a pro-beef lobbying group to get an alternative perspective. Andersen concludes with the idea that the beef industry is too powerful for anyone to stand up to, and so the government, protection groups, and similar organizations all turn a blind eye. His ending call to action is to urge the audience to go completely vegan without any animal inputs (i.e., fertilizer) whatsoever. He conducts several more interviews to show that the land needed to feed animals – if turned to feed humans instead – is more than enough for the population to go completely vegan and cut ties with animal products. Andersen ends with the moral argument of going vegan, being that we shouldn’t end another animal’s life for our own needs. The documentary concludes with examples of people successfully growing their own food for a plant-based diet to show just how possible it is.

Cinematography

The documentary seems very informative and truthful on the surface. It obviously takes the stance of wanting everyone to go vegan, but at least appears to get a range of perspectives in order to present a fuller picture from which the viewer can decide what to think. But it only appears this way. The documentary misleads the viewer to consciously and subconsciously dislike any person or viewpoint opposed to Andersen’s. The subconscious way is through the cinematography.

The two main ways Andersen misleads his viewers is through lighting / camera angles and audio cues. Each time Andersen films himself or someone presents a viewpoint with which he agrees, he edits the film to make it look more pleasing to the eyes and ears. A good example of visual deception is the juxtaposition of two interviews: one with a group he is trying to expose, and another who helps Andersen’s cause.

Figure 1: Interview with the California Dept. of Water Resources

Figure 2: Interview with Dr. Richard Oppenlander

In the first case, the interview with members of the California Department of Water Resources is strategically filmed to influence the viewer to subconsciously side with Andersen. On the other hand, Dr. Richard Oppenlander (Figure 2) supports Andersen’s cause, and so the documentary depicts him in a more positive way. This subconscious influencing is done in two ways: camera angle and mood lighting. Looking at the camera angle in Figure 1, it is set above eye-level relative to the interviewees. This kind of shot is known as a high-angle shot. The high-angle shot can range from almost directly above a subject to barely above eye-level, but the angle evokes the same emotions. In film, using a high-angle shot with characters establishes a power dynamic. If a subject is above the camera, our psychology leads us to believe they are more powerful; on the other hand, a subject below the camera leads us to believe they are vulnerable (Studiobinder, 2019). The employees at the Dept. of Water Resources are visibly below the camera angle, depicting a feeling of vulnerability. It puts Andersen (speaking off-screen) in the more powerful position, leading the viewer to believe that Andersen is the more dominant force and thus correct. Dr. Oppenlander is even with the camera, removing this power dynamic. This angle conveys a sense of equality between Andersen and Oppenlander, as the film intends. Oppenlander provided evidence supporting Andersen’s viewpoint in that interview, so it behooves Andersen to portray him in a more equal setting. This is only one example of how Andersen uses visual imagery to subconsciously convince the viewer to automatically side with Andersen’s view.

“’Low key lighting with a lot of contrast is great for communicating fear, anxiety, distrust and evilness…’”Camera angles aren’t the only visual tricks used in these two scenes, however. Lighting also plays a large role in influencing mood and opinion. Mood lighting is exploited throughout the entirety of the film in each scene and interview, so these two scenes are an accurate portrayal of the entire documentary. In viewing the two scenes again, there is a large difference in color. Figure 1 has higher contrast and more bright lighting with blue backlight, whereas Figure 2 has softer contrasts with a warmer filter applied. This tricks the brain into feeling different ways about the subjects. According to No Film School, an organization dedicated to teaching aspiring filmmakers to be better at film, mood lighting is crucial for conveying emotion. Their website comments directly on the two aforementioned points: “low key lighting with a lot of contrast is great for communicating fear, anxiety, distrust, and evilness, while high key lighting with little contrast is great for communicating happiness, peacefulness, joy, and contentment,” and, “Furthermore, the color of your light has a huge impact on the message you’re sending … Putting some blue gels on your light can make things look solemn, sad, and depressing, while using warmer gels can have the opposite effect.” (Renée, 2017). Put together, Andersen uses psychological tricks well-known in cinematography to establish himself and his supporters as protagonists and all others as antagonists.

Facts and Figures

“Fortunately, scientists have since performed an actual study of agriculture’s estimated environmental impact for greenhouse gas emissions, finding a number closer to 15%.”Cinematography is not the only area in which Andersen misleads his viewers. Being a documentary, the film is full of facts and statistics; however, not all are correct. Cowspiracy uses unsubstantiated claims and exaggerated projections to convince an unwary viewer of the dangers looming ahead. Even the backbone of his documentary, the Worldwatch report indicating that agriculture contributes 51% of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions (Hickman, 2009), is false. Links associated with the report are dead links, so Worldwatch has since likely deleted or retracted that report. Even so, the report at the time of publication is a poor example of academic research. The first problem is that the authors were advisors for World Bank, not actual environmental science academics. Secondly, their report was neither peer-reviewed nor published in an academic journal. Instead, the Worldwatch Institute published it on their own. Fortunately, scientists have since performed an actual study of agriculture’s estimated environmental impact for greenhouse gas emissions, finding a number closer to 15% (Veerasamy et al, 2015). This defeats the premise of the entire documentary, namely, that agriculture is the single largest contributor to greenhouse gases and environmental groups conspire to avoid standing up to the beef industry. There was no conspiracy after all; advocacy groups simply did their due diligence.

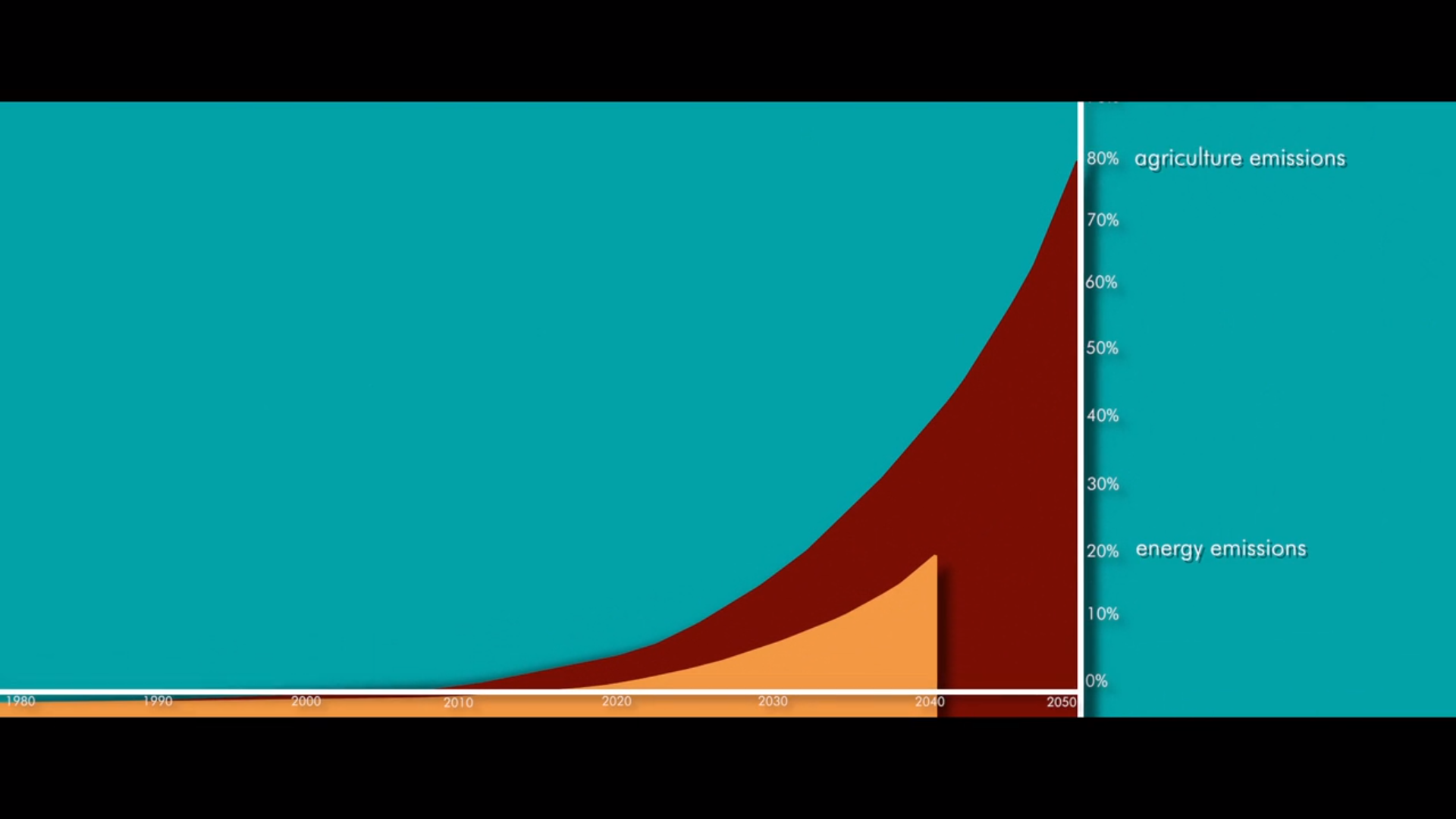

Figure 3: Cowspiracy Emissions Projections Chart

Aside from a false premise, Cowspiracy uses other facts and figures to deceive viewers. There are numerous examples, but the best is an infographic depiction in the film. Andersen’s research found two reports: one reporting projected CO2 energy emissions and one reporting projected CO2 agriculture emissions. The graphic above projects agriculture to increase a staggering 80% in CO2 emissions by 2050, whereas energy emissions has a meager 20% increase. This graphic deceives viewers in two ways: uneven projections and uneven metrics. Energy emissions only project to the year 2040. That should be the cutoff. It is misleading to compare two exponential growth curves to two different dates, but obviously a 20% vs 40% comparison of the same year is not as impressive as a 20% vs 80% difference. The illustration is deceptive in another, more subtle way. Both of these projections came from two different reports. So, with two different reports comes two different measurement techniques. The most accurate and honest way to report CO2 emissions would be to find a study that looks at both sectors together, because by doing so, the reader can be certain the same metrics are applied to emissions. But with two different reports, it is far too easy to purposely underestimate one industry and overestimate the other. It would be impractical to analyze every individual statement and source when there are well over 200 sources (Andersen, 2017), but this illustration is an excellent representative example of the statistical skewing performed in the documentary. These specious facts and premises pull the wool over unwary viewers’ eyes in an effort to expose the agricultural industry and its supposed conspirators.

Looking Ahead

Documentaries are meant to lift the veil to their audience, to uncover a hidden truth. Unfortunately, when documentaries set out to convince the viewer of a viewpoint – as opposed to letting the viewer decide for themselves – the films can become deceptive. In the case of Cowspiracy: The Sustainability Secret, the documentary did just that. It is a professional-looking feature-length film that is very captivating and easy to follow. Unfortunately, its director Kip Andersen uses subtle camera tricks and skews statistics to make himself and his allies look heroic and his opposition distrustful. A more honest version would avoid subtle psychological manipulation and use only peer-reviewed resources to present facts and statistics. By doing so, the message may not be as staggering, however, it would avoid much of the controversy it received.

References

Andersen, K., Keegan, K. (Producers), & Andersen, K., Keegan, K. (Directors). 2014. Cowspiracy: The Sustainability Secret [Motion Picture]. United States: Appian Way.

Andersen, K. (2017) The Facts. Retrieved from https://www.cowspiracy.com/facts

Hickman, M. (2009, November 1). Study claims meat creates half of all greenhouse gases. Retrieved from https://www.independent.co.uk/environment/climate-change/study-claims-meat-creates-half-of-all-greenhouse-gases-1812909.html

Renée, V. (2017, June 24). A Guide on How to Use Light to Communicate Emotion for Film. Retrieved from https://nofilmschool.com/2017/06/guide-how-use-light-communicate-emotion-film

Studiobinder (2019, July 15). High Angle Shots: Creative Examples of Camera Movements & Angles. Retrieved from https://www.studiobinder.com/blog/high-angle-shot-camera-movement-angle/#How-high-angle-shots-convey-story?

Veerasamy, S., Hyder, I., Ezeji, T., Lakritz, J., Bhatta, R., Ravindra, J.P., Prasad, C., Lal, R. (2015). Global Warming: Role of Livestock. Climate Change Impact on Livestock: Adaptation and Mitigation. New Delhi, India: Springer.