Far Less Lovely: Exploring the Need for Fair Trade Coffee

Chelsea Theobald

I am an avid coffee drinker. It’s a truth that has persisted since Middle School, when I drank what upon reflection was honestly more creamer than bean juice. Today I can be found in any given coffee shop, downing a double shot of espresso over ice to power through a full day of class. For years now I’ve been consuming coffee, hooked by the taste, the utility, and the experience of drinking it—and I’m not alone. The Washington Post reported that United States coffee consumption began breaking historic “400 million cups of coffee are consumed by Americans every day.”records in 2016. Data from the National Coffee Associations annual survey shows that on average, 64% of American’s drank a cup of coffee just yesterday, for a grand total of 400 million cups of coffee consumed by Americans every day (NCA, 2019). Millennials, the Washington Post claims, make up roughly 44% of recent consumption likely due to the rising trend of experience-oriented “coffee culture,” attracting consumers with appealing aesthetics and Instagrammable beverages (Heath,

2016). Today’s coffee industry sells an image along with a drink, wrapping its products up in a lovely little aesthetic narrative. Pictures of small bean farms along the equator cover the walls of commercial coffee chains, suggesting harmonious ties between supplier and retailer. The narrative is so convenient and pleasing that on-the-go and experience-seeking consumers alike needn’t think too much about how, when, or at what cost they will be able to get their next coffee fix. But this lovely little picture is not the full story.

My investigative project began when I read the following line from Ellen Ruppel Shell’s Cheap: The High Cost of Discount Culture: “International trade in food is critical. Life would be far less lovely for Americans without imported coffee. . . and many other nations need what we have to offer” (Shell, 2009, 186). In her book, Shell investigates the hidden costs and consequences of the increasing American demand for easily-accessed, globally-sourced, inexpensive food. The chapter in which this quotation is found, “Cheap Eats,” touched on the ways in which the environment, food quality, and human rights—among other things—are impacted by this trend. It struck a chord, causing me to think on this beloved beverage I consume, potentially at low personal- yet high collective-costs. Shell’s statement about coffee, though made in passing, spurred a need for my own personal investigation. What could be the unexpected costs of American coffee consumption?

“Life would be far less lovely for Americans without imported coffee. . .”

I began to wonder where the coffee I enjoy each day—sometimes multiple times per day—really came from and who was impacted by my daily decision to consume. I decided to investigate the global impacts of consuming coffee from commercial chains and local shops/roasteries to the best of my ability, acknowledging my love for coffee by no means makes me an expert. I expected that the United States’ massive demand for coffee would have at least some consequences for global affairs, particularly impacting those at the source. What I didn’t expect was just how unaware I was that behind so many trendy coffee shop aesthetics and viral latte photos were cases of untold exploitation.

Take for instance, this story of a family of coffee farmers from Uganda, described in scholar Bill McKibben’s book Deep Economy (2007). An interview with the family left their patriarch in tears upon his learning with utter disbelief from the translator that one cup of coffee sold in Starbucks amounts to the equivalent of 5,000 Ugandan shillings. The farmer, who was no longer able to afford to send his children to school, told his interviewers that he received only 200 Ugandan shillings for one kilo of coffee that year, far greater an amount of coffee for far less the price (McKibben, 2007, 192-193). How could it be that a product in such high demand in the US (remember, 400 million cups consumed every day) be leaving its producers in such economic depression (NCA, 2019)?

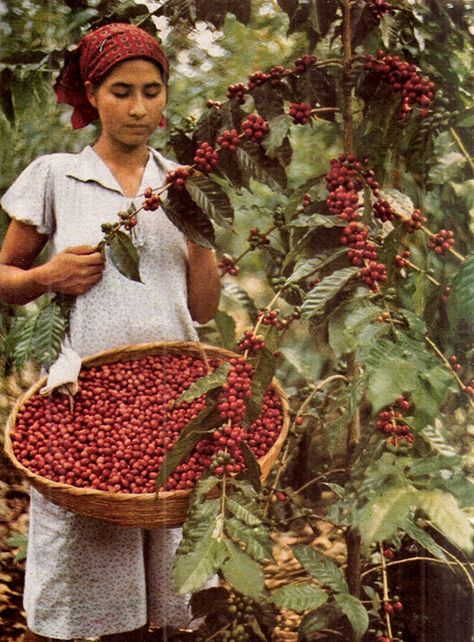

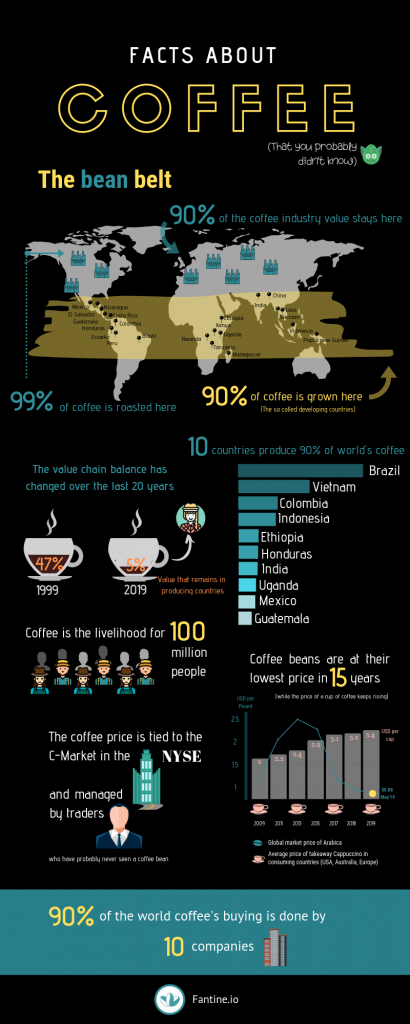

90% of coffee beans consumed globally are sourced from the “Bean Belt,” a group of 45 countries near the equator with the ideal agroclimate for growing coffee beans. Many of the countries farming these beans are considered developing countries and have historically been, and arguably continue to be, exploited by global powers and commercialization. In fact, while demand for coffee is at an all-time high and major coffee chains like Starbucks have increased their coffee prices in the last several years, there is a “Coffee Crisis” occurring within the Bean Belt. Coffee prices for suppliers are at the lowest they have been in 15 years such that many farmers earn less than 5% of the profits made by commercial retailers from selling a cup of coffee (Fantine, 2019; see figure 1). In Honduras, for example, coffee farmers are facing prices at 1/3 what they were only eight years ago, cutting small farmer’s wages by over 66% while profits in North America continue to rise with popular demand (North, 2019). McKibben’s discussion of the Ugandan coffee farmer’s pain and grief upon learning Starbuck’s selling price for coffee compared to his own earnings is not unique, but that doesn’t make it any less tragic or unjust.

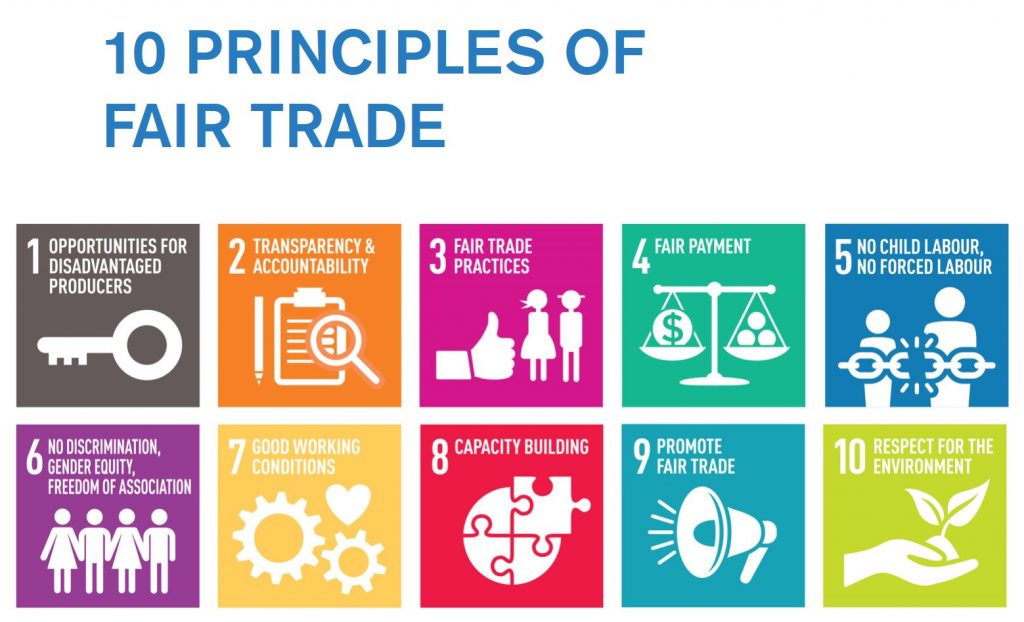

I was floored by these findings. I thought certainly legislation and trade rules must be in place to protect the suppliers of such a highly valued commodity, and soon found that there are initiatives in place to protect these farmers: the Fair Trade system. Fair Trade coffee is supposed to help small farmers with this kind of crisis by setting a consistent, reasonable price to be paid for coffee at all times, regardless of the market value. The problem, however, is this is an optional standard. Companies in the industry can choose whether or not they want to partner alongside Fair Trade coffee farmers. According to the World Fair Trade Organization (WFTO), there are ten principles that must be met in order for a trade partnership to truly be “Fair Trade,” including, in addition to fair prices, protections of human rights, respect for the environment, and opportunities for disadvantaged producers (WFTO, 2019; see figure 2).

Since Fair Trade practices of coffee were formally established in 1989, there have still continued to be coffee crises in the Bean Belt such as the one in Honduras today. So why isn’t this Fair Trade Standard working? The answer may largely have to do with the fact that people either assume it is already common practice or misunderstand what it is and why it exists. I interviewed several coffeeshop-goers to ask what they look for in their go-to coffee shop. Most replied something along the lines of going wherever their friends go, where there is a good “study environment”, or where they have “quality coffee.” Following up to ask what “quality” meant to one consumer, she replied that it had to do with the taste. “Starbucks coffee is too bitter,” she stated, and she is very perceptive. Huge chains like Starbucks tend to favor a dark roast of their beans, which is cheaper and ensures a uniform, albeit bitter, taste across the chains’ numerous locations (Stoffel, 2019). To finish the interview, I asked this consumer how common she thought Fair Trade practices are, to which she replied “I don’t think it’s super common but I do think there is an awareness now. . . I guess I assumed it’s become common knowledge and I just haven’t asked [local shops if they source Fair Trade coffee].” It appears that many consumers, like myself, get swept up in the taste and aesthetic of coffee and the shops that sell it as we routinely consume day after day. We purchase the image that commercial chains sell us along with our caffeinated beverage via their earthy coffee labels and artsy equatorial landscape décor—the innocent presumption that their coffee is already sustainably or ethically sourced.

This is partially due to the problem of “Fairwashing” in which coffee suppliers oversaturate the market with meaningless labels in an attempt to win over globally-conscious consumers. When I started looking deeper into coffee sales and their product sourcing, I found that labeling coffee as “Fair Trade” wasn’t the only way to differentiate coffee beans. Roasteries and coffee shops alike use a number of similar tags in an attempt to enhance the credibility of their product. Every coffee shop in Bloomington that I researched had something to say about their coffees’ certification by at least one or two labels and organizations. Though I have been drinking coffee for almost a decade, I realized I had no idea what these labels actually signified, and I found many to be craftily worded, marked with loopholes and unclear exceptions (see table 1).

| Label | Certifies that. . . |

| Fair Trade | Coffee beans have been grown according to the ten Fair Trade Principles: Opportunities provided for disadvantaged producers, transparency and accountability, fair trade practices, fair payment, no child or forced labor, no discrimination, good working conditions, capacity building, promotion of fair trade, and respect for the environment. |

| Fair Trade Certified | Coffee beans have been grown on farms that meet standards protecting the safety and wages of workers. Unlike Fair Trade, these farms could be large plantations rather than small, local farms. |

| USDA Organic | Coffee is grown with soil protection in mind, meaning the absence of synthetic fertilizers or synthetic pesticides used on coffee beans. Does not necessarily indicative of the protection of workers’ rights or biodiversity conservation. |

| Bird Friendly | Coffee is grown on farms that protect native habitats for local wildlife in order to preserve biodiversity. |

| Rainforest Alliance | Coffee was grown while keeping sustainability in mind. However, label can still be given to a bag of coffee if some coffee in the bag was not grown under the same level of desired conditions for conservation. |

Table 1: Breakdown of common coffee bean labels. Source: Washington Post Consumer Reports “Organic? Fair-trade? The Truth About Coffee Labels” (2017, November 25)

Separate from these official accreditations, coffee producers may label their beans as “ethically sourced” or “sustainable.” These subjective labels could mean anything, consequently leaving them with little value or integrity for discerning source quality. Such a wide spectrum of labels, with little explanation outside of perceived good intentions or targeted marketing ploys can be confusing for consumers. Coffee lovers hoping to make a difference in the global coffee trade could easily wind up purchasing “ethical coffee” that is actually not Fair Trade, but rather it meets the seller’s standards without necessarily keeping local farmers of the Bean Belt’s best interests in mind. “Ethically” sourced coffee could mean protected workers’ rights and sustainable practices, or it could mean absolutely nothing at all.

This becomes especially problematic when it pertains to big commercial chains such as Starbucks. Starbucks actively and openly advocates for their Coffee and Farmer Equity, or “C.A.F.E.” practices, but in fact only two of Starbucks’ many bean sources are Fair Trade Certified (North, 2019). This is not to say that these practices are necessarily negligent or unfair, rather to highlight the fact that that the chain’s standard of ethics is “Last year Starbucks brought in $4.52 billion in net profits. In the same year, coffee bean farmers faced a devastating price collapse for their beans.”internally monitored. Without outside regulation to keep multiple parties’ interests in mind, how can consumers be confident that Starbucks isn’t taking advantage of setting their own rules and price points for what constitutes “fair?” For instance, last year Starbucks brought in $4.52 billion in net profits (North, 2019). In the same year, coffee bean farmers along the bean belt faced a 2/3 price collapse such that if no minimum reasonable price has been established these farmers are unable to make a living.

As a world leader in the coffee industry, Starbucks has a responsibility to be modeling the sustainable consumption of coffee. The truth is that many people will live their life unaware of the existence of Fair Trade and will keep consuming familiar brands without knowing the global cost. As it stands, there is an oversupply of Fair Trade coffee. Certified Fair Trade growers are currently having to sell approximately 2/3 of their supply into the regular market at lower prices, pointing to the fact that unless major importers like Starbucks decide to accept the Fair Trade system it may never reach its full potential (North, 2019).

I was pleased to find many coffeeshops in my college town of Bloomington, IN, included some statement about Fair Trade on their websites. At times it was unclear the extent to which they were actually sourced by certified Fair Trade farmers, but at the very least the awareness of Fair Trade’s importance is a positive step. According to their website, local Bloomington shop Needmore Coffee, for instance, is 100% Fair Trade and organic. Another student favorite, The Pourhouse Cafe, says their coffee is “fairly traded” but does not specify the extent of their source’s certifications.

One concern for small roasteries is that Fair Trade is expensive to maintain compared to other, non-regulated options. Local coffee shops are already forced to compete with commercial chains. The added weight of maintaining a sustainable bean source can be both a blessing and a curse. From another perspective, for instance, marketing a sustainable strategic position could increase a small mom and pop store’s competitive advantage. This position, however, would be dependent on the community’s awareness of Fair Trade and their value of its implications, further emphasizing the need for education and awareness of Fair Trade practices.

This exploration of Fair Trade coffee practices in response to global consequences for the massive demand for coffee consumption definitely opened my eyes. Even without discussing the massive amounts of instant coffee that is sold and consumed outside of coffee shops in the United States, the impact of U.S. coffee consumption on the globe is staggering. In a world where so much progress is being made, especially from the plush perspective of an American in an industrialized, wealthy state, it can be easy to get swept up in the hope that “everything is better.” I took for granted the idea that more people have jobs and protection of their rights than ever before. I got swept up in the excitement of coffee culture and the trendy aesthetics that cover more sobering images of exploitation. As I sipped my second cup of coffee of the day, I forgot to remember the farmers who worked to ensure I am able to have it.

References

“Fair and Transparent Coffee Trading.” Fantine, 9 Dec. 2019, www.fantine.io/.

Heath, T. (2019, March 28). Look how much coffee millennials are drinking. The Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/business/wp/2016/10/31/look-how-much-coffee-millennials-are-drinking/.

McKibben, B. (2007). Deep economy: The wealth of communities and the durable future. Macmillan.

National Coffee Association (NCA). (2019). Infographic: The Behaviors & Perceptions of US Coffee Drinkers. Retrieved from http://www.ncausa.org/Industry-Resources/Market-Research/NCDT/NCDT-Infographic.

North, J. (2019, October 29). Coffee Prices Have Collapsed, Threatening the Livelihood of Millions Across the Global South. The Nation. Retrieved from https://www.thenation.com/article/coffee-starbucks-honduras-fairtrade/.

Savage, Jessica. “Local Starbucks Increases Instagram Following by 62%.” WDYT, 15 June 2017, www.wdyt.org.uk/2017/06/13/local-starbucks-increases-instagram-following-62/.

Shell, E. R. (2009). Cheap: The high cost of discount culture. Penguin.

Stoffel, Brian. “The Bitter Truth About Starbucks Coffee.” Medium, Medium, 24 Sept. 2019, medium.com/s/story/the-real-reason-coffee-at-starbucks-tastes-bitter-and-burned-b4ab8ab81919.

Washington Post Consumer Reports. (2017, November 25). Organic? Fair-trade? The truth about coffee labels. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/national/health-science/organic-fair-trade-the-truth-about-coffee-labels/2017/11/24/8ec4b726-b42c-11e7-a908-a3470754bbb9_story.html.

World Fair Trade Organization (WFTO). (2019, November 19). Who We Are. World Fair Trade Organization. Retrieved from https://wfto.com/who-we-are#the-president–and-the-board.