“Good Enough” isn’t Good Enough

Food Pantries and Nutritional Aid in America

Bryn Eudy

Imagine, for a moment, adding an extra errand every month. If you live in a rural area, it’ll take time and gas money to get there. If you live in an urban area, you’ll hope you arrive soon enough to not have to wait long in line. Either way, you might have to take time off work. You’ll enter the building, seeing stacks of shelf-stable food. Maybe some fresh food. You’ll get what you can, maybe it’s a pre-made box of assorted goods, or maybe you can wander the aisles and choose what your family would like. This is, in very simple and broad terms, what some individuals in the United States do every time food is needed – they go to a food pantry.

When examined holistically, food could be said to serve two purposes. We need it to live, obviously. But it serves another purpose, too. It’s a connector to comfort. Food is undoubtedly tied to concepts of family and culture. Just imagine the feeling of coming home to your favorite childhood meal. While there’s ubiquitous feelings attached to food, there isn’t ubiquitous access. In the United States, a country known for its love of excess, there are citizens without access to food. As the holiday season approaches, food pantries will receive donations from groups far and wide – from churches to student groups to individuals looking to make a difference in the lives of those in need. However, these donations don’t always match up to what is needed. It seems as though there’s a gap between what individuals believe they should give and what food pantries need to be able to provide healthy, quality products to their shoppers.

Those who require the use of food pantries or other supplemental aid to afford healthy food fall under the umbrella definition of “food insecure”.

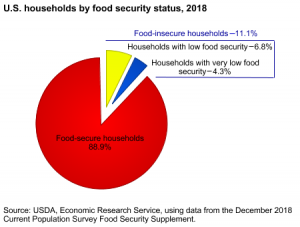

Food insecurity in the United States doesn’t necessarily mean that someone lacks access to food. Instead, it’s used to define the type of food available. According to USDA data, 13.5 percent of Indiana households are food insecure (Coleman-Jensen) compared to the national average of 11.1 percent. Indiana is one of only twelve states to have above-average food insecurity. Causes for being food insecure can range from living in a food desert to socioeconomic status, with a myriad of factors in between. Food insecurity has consequences, too. Poverty and chronic illnesses, like diabetes and high cholesterol, have ties to quality of diet which is linked to food insecurity. For example, 33% of households that utilize food pantries have at least one family member with diabetes (Diblasio).

When considering the use of food pantries and their complexities, it’s important to consider nutrition access in broader terms within the United States. Some who use food banks and pantry services are enrolled in public nutrition programs, commonly referred to as food stamps or the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). SNAP provides food assistance to low and no income individuals. It is a federal aid program administered by the Food and Nutrition Service of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, and distribution of benefits occurs at the state level. In Indiana, the Family and Social Services Administration is responsible for ensuring that SNAP regulations are implemented and consistently applied in each county (Family and Social Services Administration). However, SNAP is not designed to meet a household’s entire food costs. Benefits are intended to supplement the household’s income to help purchase healthy food options during the month. In addition to SNAP, there is an additional nutrition aid to pregnant women, infants, and young children. The Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children, commonly referred to as WIC, is a federally funded program that assists with supplemental foods and nutrition education for low-income pregnant and post-partum women, as well as children up to the age of five at nutritional risk (Food and Nutrition Service).

“Having food line our cabinets again meant there was light at the other side of what he had been through.”

The type of foods eligible to Indiana families enrolled in the WIC and SNAP programs have a few gaps. Unfortunately, organic milks, cheeses, and juices are not eligible. Low cholesterol, organic, or free range eggs aren’t covered by either program. Fruits and vegetables and lean meats are covered, but in limited amounts. Sugary and over processed food are excluded as well. While it’s evident that health standards were taken into account when categorizing food as covered or ineligible, the program can still easily leave families food insecure. As previously mentioned, SNAP and WIC aren’t intended to cover all food consumption. This is where food pantries have the opportunity to be the provider of healthy food to families. To fill gaps left by public aid, food pantries often don’t have income requirements for someone to have access to their services.

Gaps in nutrition assistance programs are illustrated in The New York Times article “Their Lives Changed in an Instant. A Food Bank Helped Them Recover.” The article examines the story of the Perez family from Davenport, Iowa, who struggled with food insecurity. Following a child’s traumatic brain injury, only one parent in a household with four children was able to work. Their income was above the income level that SNAP would serve, so they turned to a local food pantry for access to healthy food. Stacy Perez, the mother interviewed in the article, said “Having food line our cabinets again meant there was light at the other side of what he had been through” (Peragine). While her family’s situation was temporary, they were food insecure due to unexpected lower income and high medical bills.

To help close the gap on food insecurity, communities, food banks, and food pantries work together. Food banks are warehouses to store food before it is distributed to food pantries, that actually have the face-to-face interactions with community members in need of food. One in seven Americans rely on food pantries, according to the Washington Post (Diblasio). Of those who use food pantries, 79 percent report purchasing inexpensive, healthy food to have enough to feed their families (Diblasio). In Bloomington, Indiana – our college town in Monroe County perched in the hills of southern Indiana – there’s a handful of organizations working to provide food to those who need it. According to a 2015 study from Feeding America, 22% of Monroe County residents are food insecure. Mother Hubbard’s Cupboard is a local organization which provides access to healthy, fresh food as well as a space for learning to garden and cook. Founded in 1998, Mother Hubbard’s Cupboard has  served the Bloomington community for more than twenty years. Their growth maps the changing ideas as to what communities need to become food secure. Beginning in the 2004, they began tending a section of a community garden. In 2011, they expanded their food education program outreach and doubled their gardening space. In 2014, they expanded out of nutrition services, to address other community needs, like voter registration, healthcare, and housing – working to connect residents to additional services. Then, in 2016, they opened The Hub Tool Share, an innovative program that propelled Mother Hubbard’s Cupboard toward offering as much fresh, nutritious food as possible (Mother Hubbard’s Cupboard). The Hub reduces barriers such as not having the correct cooking equipment to prepare fresh foods while employees and volunteers make home gardening and nutritious, healthy options available to food insecure. This multitude of services is vastly different from the stacks of canned goods one could expect to see in a pantry.

served the Bloomington community for more than twenty years. Their growth maps the changing ideas as to what communities need to become food secure. Beginning in the 2004, they began tending a section of a community garden. In 2011, they expanded their food education program outreach and doubled their gardening space. In 2014, they expanded out of nutrition services, to address other community needs, like voter registration, healthcare, and housing – working to connect residents to additional services. Then, in 2016, they opened The Hub Tool Share, an innovative program that propelled Mother Hubbard’s Cupboard toward offering as much fresh, nutritious food as possible (Mother Hubbard’s Cupboard). The Hub reduces barriers such as not having the correct cooking equipment to prepare fresh foods while employees and volunteers make home gardening and nutritious, healthy options available to food insecure. This multitude of services is vastly different from the stacks of canned goods one could expect to see in a pantry.

As reported by NPR, “[Food pantries] often get large donations from folks who are obviously cleaning out their pantries. While we appreciate all donation efforts, we encourage people to only donate what they themselves would feed their families … Large donations of canned foods that are five-plus years past their expiration dates, sadly, are not helpful” (Gane). “Large donations of canned foods that are five-plus years past their expiration dates, sadly, are not helpful.”A quick Google search for “What to donate to food banks” yields results including “Unwanted Products? Donate to a Food Bank!” and “What’s the best non-perishable food to donate?”. The first of these results shows a difficult decision-making process. Should food pantries be a place for individuals to donate unwanted food? With a narrow point of view, this does not seem like the worst idea. Consumers who understand the massive amount of food waste the United States has might not want to throw away their old or unwanted food. However, what does it say about empathy and respect for those using food pantries if they are thought to be receptacles for what isn’t “good enough” for the person who originally purchased the food? Once the food donation process and its potential pitfalls are examined a bit closer, it becomes evident that donating the canned goods one decides they don’t want isn’t as beneficial as other options. While this type of donation is a very popular vehicle for group donations in the form of a “can drive”, this type of canned or non-perishable food isn’t always the healthiest. High salt content and a host of other preservatives aren’t healthy when eaten in large quantities.

While these facts and figures could lead someone to think that there is no such thing as a “good” donation to a food pantry, there are other options. Cash and time. Pantries know how to make dollars stretch while buying in-demand, healthy food. In an interview with Slate, Katherina Rosqueta, executive director of the Center for High Impact Philanthropy at the University of Pennsylvania, explained that food providers have the ability to purchase in bulk “pennies on the dollar,” estimating that it costs food banks just ten cents a pound for food that would cost the regular consumer $2 per pound in a retail setting (Yglesias). From an economical lens, consumers would be better off donating the money that they’d spend on purchasing food than actually purchasing it. Similarly, pantries also have a better idea of what their frequent shoppers prefer to eat. They know if a family has food allergies or can’t eat certain foods for religious reasons. They also need volunteers to keep their organizations running. Someone has to sort through canned donations, after all.

It’s easy to feel as if there isn’t much hope at the end of the day on this topic. What were once thought to be considerate donations are realized to be unhelpful and even burdensome. Even with nutritional aid and food pantries, more than a tenth of the nation doesn’t have enough healthy food to sustain their families. The question of where we go from here is a difficult one. Food insecurity can be tied to so many aspects of society – stereotypes and prejudices of social class, race and geography run deep in ideology and policy in a way that can be hard to undo. And while it might be a bold and a bit optimistic of a view, I’d like to hope that a simple, yet meaningful solution can be found. Every step taken by someone choosing to donate or volunteer at a food pantry or food bank is a step in the right direction. Perhaps SNAP eligibility can be calculated to include more participants. Food pantries and banks could grow to support more individuals. More research could be publicized on the importance of access to healthy meals. In the land of plenty, surely there can be a solution to feed America’s hungry.

References

Coleman-Jensen, Alisha. “Key Statistics & Graphics.” United States Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service, United States Department of Agriculture, 4 Sept. 2019, www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-us/key-statistics-graphics.aspx#foodsecure.

Diblasio, Natalie. “Hunger in America: 1 in 7 Rely on Food Banks.” The Washington Post, 20 Aug. 2014.

Gane, Tamara. “Opinion: Being Hungry In America Is Hard Work. Food Banks Need Your Help.” NPR, NPR, 30 June 2019, www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2019/06/30/735881297/opinion-being-hungry-in-america-is-hard-work-food-banks-need-your-help.

Gundersen, C., A. Satoh, A. Dewey, M. Kato & E. Engelhard. Map the Meal Gap 2015: Food Insecurity and Child Food Insecurity Estimates at the County Level. Feeding America, 2015.

Peragine, John. “Their Lives Changed in an Instant. A Food Bank Helped Them Recover.” The New York Times, 2 Nov. 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/11/02/neediest-cases/food-bank-accident-iowa.html

Yglesias, Matthew. “Why Food Drives Are a Terrible Idea.” Slate Magazine, Slate, 7 Dec.

2011, https://www.slate.com/business/2011/12/food-drives-charities-need-your-money- not-your-random-old-food.html.

Family and Social Services Administration. “Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program.” FSSA: About SNAP, IN.gov, www.in.gov/fssa/dfr/2691.htm.

Mother Hubbard’s Cupboard. “Growing, Growing, Growing… .” Mother Hubbard’s Cupboard, www.mhcfoodpantry.org/mhc-history.

Food and Nutrition Service. “Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC).” U.S. Department of Agriculture, www.fns.usda.gov/wic .