From Farm to Factory

How consumer demand for cheap food has affected the practice of farming

Calvin Isch

Life of a farmer

My grandfather was the platonic ideal of a 20th-century farmer. Every morning he would wake up at the crack of dawn, hop on his loader tractor and begin his day on the land. When I dream of the archetypical family farmer, I imagine what his life looked like in the 1970s…

Looking around the ‘70s cornfield you might not have even noticed him. A natural farmer, he fit the part so well that he seemed an integral part of the landscape. He was completely at home atop his ancient tractor; the farm would be lonely without him. He would start each day at the barn lot, checking on the cows. After a grueling two hours of milking, he would begin examining the field. In the evening he would head to the “shop,” a giant complex from a mechanic’s dream, where he’d work on his old equipment, preparing it for the next day. While his practices then were very different from the way he farmed as a child, everything remained personal. He had a manageable number of animals and an amount of land that seems traversable. Most importantly, he and his family worked on the farm together and were connected to their practice, connected to the crops, the animals, the equipment, and the land. It is the life they always expected they’d live, the life of Grandpa’s father and his grandfather before him. While he’s no longer with us, I’m certain that Grandpa never would have expected the changes looming ahead.

The Changing Indiana Farm

Fast forward forty years, and my grandparents’ farm is vastly different. They’ve expanded the farm to encompass 100 more acres—a 33% increase in land. While they still own the land, they don’t even tend it themselves—one of the neighbors has taken it on as part of the five-thousand-plus acres of land they harvest. The cows are gone, replaced by their two sons’ hog business: this duo rears ~8,000 pigs at their new facilities. Grandpa’s trusted equipment has been sold away, no longer needed. Their farm is different in almost every way, which leaves one wondering: are the changes to my grandparent’s farm the exception or the rule?

Every year, the Department of Agriculture (DOA) performs an agricultural census where they report on the state of farming in the country. In one of their reports (1977), they state that in 1969 there were 101,479 farms in Indiana Farms are exploding in size as fewer individuals suck up more of the land from those around them.with an average size of 173 acres. By 2017 the number of farms shrank by almost half–down to 56,649 farms with an average size of 264 acres (DOA 2019). These farms are exploding in size as fewer individuals suck up more of the land from those around them. Farms aren’t just increasing in area—the number of animals being raised is also skyrocketing. In 1969 the average Indiana pig farm had 127 pigs (DOA 1977). While a large number, it seems like an individual could actively consider and care for this number of animals. By 2017, the average hog farm increased over 10-fold in size, now hosting 1,558 pigs (DOA 2019)! Clearly, there has been an explosion of size and efficiency of farming practices across the state; the changes in my family farm aren’t exceptional; they are the norm.

Agents of Change

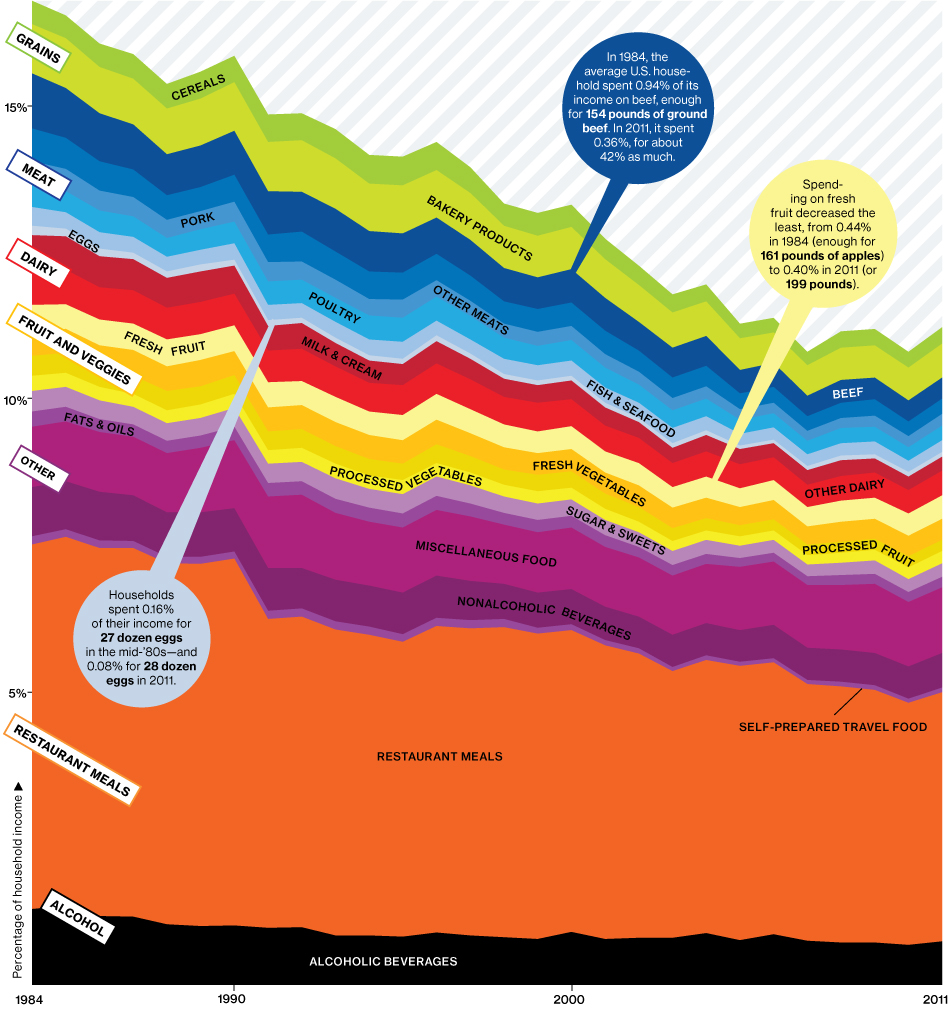

Farmers aren’t creating these changes in isolation from the rest of the world; in fact, consumer demand plays a pivotal role in shaping how production is structured. Looking at consumer purchases, it’s evident that one word trumps all else when it comes to food: cheap. To see the growing importance of cheap food, take the example of price-leading retailers, such as Walmart or Kroger. These stores specialize in offering low prices, and consumers have responded to these prices by buying more of their products over time. In 1992, the 4 largest retail stores sold 16% of all grocery sales in the US, but by 2016, that percentage had jumped to 44% (Martinez & Elitzak 2019). Now Walmart is the biggest supplier of groceries in America, taking in over $500 billion in revenue each year (Cain 2019). We as a nation are giving more of our money to the biggest companies, while at the same time we’re spending less of our income on food. The diagram below marks the decrease in proportion of net income spent on food in the US, since the 1980s (Thompson 2013).

Through purchases of cheap goods, consumers tell corporations like Walmart that what they care about the most with food is the price tag it comes with. These companies respond in kind by demanding that the producers continue to create more food at ever-decreasing prices.

When price competition is the name of the game, entities that produce products more efficiently with fewer resources naturally emerge as the market champions. In farming, this competition has led to large corporations dominating the landscape. These companies create new technologies and innovations that lead to many of the changes seen on my grandparents’ farm. Two especially transformative innovations are those associated with farm equipment and the advent of factory farming animals. Improved farming equipment leads to obvious changes: it allows farmers to tend larger swaths of land in less time, an effect that is compounded by recent advancements in herbicides, pesticides, and genetically modified crops. This process has led to the massive growth of the average farm and the similarly massive decrease in the number of individuals who continue to farm it. The effects of factory farming are more pernicious and nuanced.

The farm becomes a factory

To a typical farmer, the abstract idea of a factory farm may seem like a panacea to the trouble of animal rearing. People like meat and everyone should be able to afford the things they like. Factory farming allows farmers to feed people all over the world food they crave at a low price. At the same time, efficiencies are achieved so the farmer can make good money as they produce the food. While enticing, factory farming comes with many negative consequences. These issues come from the sheer scale of production.

A massive factory farm comes with a similarly massive price-tag. Greg and Doug Isch, my grandfather’s sons who own the hog business, went over a million dollars in debt to create the facilities to run their pig operation. As savvy as they may be, many farmers do not realize the magnitude of this sort of investment. It takes decades to pay off a figure of that size, and the initial cost is only one piece of the puzzle. “The contract is set up so that the [corporation] owns the pigs…they control everything in the process.”According to the National Hog Farmer, a news outlet that keeps farmers up to date on everything related to hogs, a typical hog farm can revamp or even remodel their buildings 1-3 times over the course of 20 years (Miller 1998). As a result, the initial promises for high pay are left unrealized. Greg pointed out another hidden cost that farmers often overlooked: “The contract is set up so that the [Corporation] owns the pigs…they control everything in the process.” Did you catch that? The farmer doesn’t even own their pigs. The hogs belong to the larger company and without freedom of ownership, the farmer is left with few options: keep up with the changing demands of the company or be completely without hogs to pay off their expensive buildings. Thus, once a farmer signs an agreement with a larger corporation, they are completely stuck following their demands for the next twenty years just to pay off their investment.

In addition to the hidden financial costs associated with factory farming come a number of more intangible “spiritual” costs. To investigate these costs, I spoke with a man from southern Indiana named Joe, whose family raised animals in the 1950s. Joe has fond memories of many of the individual animals they raised. A revealing comment came from his description of one of his favorite, nameless goats, “he was my buddy…he had personality.” This was a sentiment common among many farmers of his time. With fewer animals, farmers got to know each one, got to see the life behind the eyes of the commodity they raised to make a living. “In our area…farmers view [pigs] as they would any other asset: they are a way to make a profit.”While Joe’s family still butchered his goat, he connected emotionally to the animal while raising it. In contrast, animals on large scale farms are viewed as products—materials on a conveyor belt in a factory. When I asked Greg Isch about typical perspectives of pigs on his 8,000-hog farm he said, “In our area…farmers view [pigs] as they would any other asset: they are a way to make a profit.”

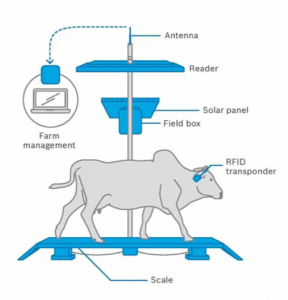

This objectification of animals is explicitly intentional and comes with many problems. Large corporations who partner with farmers utilize a practice called “precision livestock farming” to optimize the development of their “products” (Bosche 2018). This method uses process engineering, the same methods that oil companies use to get oil out of the ground, processed, and into our cars, in as fast and efficient a manner as possible. Such a method naturally turns the animals into objects, and resultantly, the harsh conditions that the animals face are ignored by those who used to look at them as friends. Thus, pigs are housed by the thousands in small facilities, and both they and surrounding areas suffer the consequences. The animals live painful short lives, doing little outside of eating and turning that food into manure. Because of the size of operation, this manure is highly concentrated such that it seriously affects the surrounding environments—killing ecosystems, polluting the air, and even creating new pathogens (LEPLC 2019). These are some of the consequences of increasing farm size, but the greatest threat to a traditional farmer’s way of life comes as a necessary consequence of endless growth.

The death of the family farm

The natural end to consumer demand for cheap food is the death of the family farm. As more cheap food is bought, large corporations who specialize in low-priced goods have more capital to innovate and demand efficiencies. The producers below them then create better equipment, pesticides, and crops, allowing more product to be planted by an individual farmer. Thus, economies of scale are realized which ultimately leads to a further decrease in price for most crops. This feeds the consumers’ desire for cheap prices and creates an expectation that prices should remain cheap forever. The cycle continues, and farmers are faced with two choices—buy more land and realize economies of scale themselves or get out of the business entirely. While many may perceive this as a positive trend, farmers who’ve spent their entire lives on the same plot of land do not. My grandfather was such a farmer. He took so much pride in his practice, and he believed he was doing good. He was feeding the world the food it desired, and he enjoyed the process of providing it. His greatest hope was that his children and grandchildren would continue the tradition and carry on the family farm in years to come. For better or worse, this dream is dead—the land he worked so hard to cultivate will surely be sucked up by the neighboring farms that are looking less and less like family operations and more and more like large industrial complexes.

Moving forward

Looking ahead, it is clear that consumer demand for cheap food presents a number of issues to Indiana farmers. As they attempt to make a solid buck while providing people with the cheap meat they crave, farmers create massive complexes and incur debt that takes decades to escape. As they raise thousands of animals, those animals naturally become objects in the chain of production. As they improve the efficiency of their processes, they drive down prices and inevitably force every farm to grow or get out. Thinking about the future problems associated with farming—the environmental cost of our current practices, the potential tragedies associated with raising animals in factory settings, and the loss of the family farm—we need to keep these complexities in mind. Farmers are responding to the demands placed upon them by the market. They care about their practices and are willing to change, but only if the solution is economically viable and leaves everyone with food on the table.

While the farming world we are moving to is one my grandpa never would have imagined, it’s the reality of our time. The road to a brighter future for the Indiana farmer comes when we take the world as it is, look our present problems in the eye, and strive to understand the effects of our choices. By demanding cheap food, we create incentives for farms to grow, depersonalize, and optimize efficiency at the price of environmental and quality costs. If we as consumers hope to create a world that gives farmers the same pride that my grandfather had for his practice, we need to start looking at things other than the price-tag when we buy meals for tomorrow.

References

Bos, J. M., Bovenkerk, B., Feindt, P. H., & Van Dam, Y. K. (2018). The Quantified Animal: Precision Livestock Farming and the Ethical Implications of Objectification. Food Ethics, 2(1), 77-92.

Bosche (2018). A closer look at precision livestock farming. Retrieved from https://blog.bosch-si.com/agriculture/a-closer-look-at-precision-livestock-farming/

Cain, Á. (2019, September 5). The 10 largest grocery chains in the world by sales. Retrieved from https://www.businessinsider.com/walmart-costco-7-eleven-kroger-lidl-biggest-grocery-chains-world-2019-9#1-walmart-10.

Martinez, S., & Elitzak, H. (2019, August 20). Retail Trends – Economic Research Service DOA. Retrieved from https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-markets-prices/retailing-wholesaling/retail-trends.aspx.

Miller, D. (1998, August 1). Raze or Remodel. National Hog Farmer. Retrieved from https://www.nationalhogfarmer.com/mag/farming_raze_remodel

Thompson, D. (2013, March 8). Cheap Eats: How America Spends Money on Food. Retrieved from https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2013/03/cheap-eats-how-america-spends-money-on-food/273811/.

U.S. Department of Agriculture (1977) 1974 Census of Agriculture. Retrieved from: http://usda.mannlib.cornell.edu/usda/AgCensusImages/1974/01/14/304/Table-01.pdf

U.S. Department of Agriculture (2019) 2017 Census of Agriculture. Retrieved from: https://www.nass.usda.gov/Publications/AgCensus/2017/Full_Report/Volume_1,_Chapter_2_Co

U.S. Department of Agriculture (2019) Indiana Agricultural Statistics 2017-2018. Retrieved from: https://www.nass.usda.gov/Statistics_by_State/Indiana/Publications/Annual_ Statistical_Bulletin/1718/IN1718Bulletin.pdf

Water Quality Issues Associated with Manure. (2019, August 14). Livestock and Poultry Environmental Learning Community (LPELC). Retrieved from https://lpelc.org/water-quality-issues-associated-with-manure/.