The Indiana University eText Experience: The Economics

6 The Role of Physical Bookstores for eTexts

Brad Wheeler, IU Vice President for Information Technology and Chief Information Officer; Professor of Information Systems, IU Kelley School of Business

For many colleges and universities, no topic is more mobilizing or constraining for an eText initiative than the goals, opportunities, and constraints of the campus bookstore. Two questions can provide essential clarity:

- What role should a physical bookstore play in the transaction between digital content creators (publishers) and content consumers (students)?

- What is the cost and value to students of this role for the bookstore?

Institutions with clear answers to these questions will have greater clarity in shaping their eText initiatives. Without goal clarity, a proposed eText initiative and the bookstore risk becoming an internal proxy for conflicting institutional goals—the internal “family feud” from the previous section.

The Economics of Goals and Sourcing

There are certain retail operations and inventory for which a campus bookstore in a great location with high traffic is ideal. Those may include sales of university sweatshirts, memorabilia, sundry goods, a café, and other unique or convenience items. They may also include large inventories of new and used books per the requests of the faculty, and bookstores may play critical roles in gathering course materials requirements for each section. Bookstores require capital investment, skillful management, space, and staff to operate, and all of these costs must be recovered in mark-up on the costs of the items they sell if the goal is to lose no money or to possibly make money.

Over the last 15-20 years, many, but not all, institutions have chosen to get out of the business of owning and operating their bookstores. Several large chains generally won most of the outsourced deals, and they brought relationships with publishers, warehousing and distribution for physical goods, expertise, branding, and cash upfront to take over campus bookstores under sale or other contractual arrangements. Institutions ridded themselves of trying to run a business that was not their strength, received a large cash payment up front, and an ongoing revenue stream from some fixed or profit-sharing arrangement on sales in exchange for some terms of exclusivity.

Institutions leased space and a campus brand by entering into a mutually valuable contract with an experienced operator, and those contractual terms for the deal were often established via a rigorous bidding process. This proved to be a winning formula for most everyone, and retail pricing of books was constrained by a growing online market and alternative places to acquire books just as Amazon and others do for most goods.

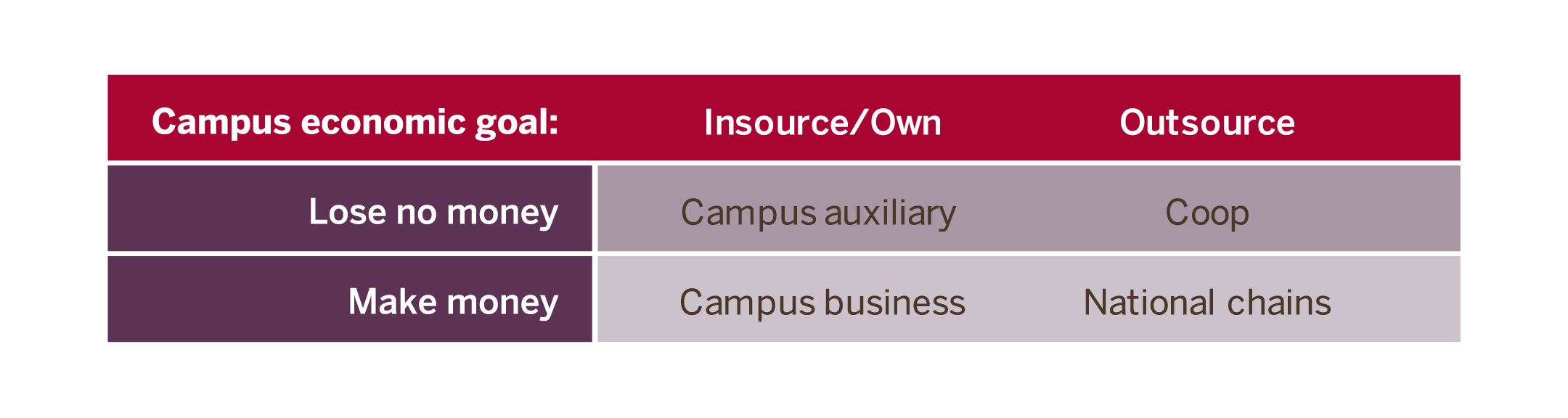

The figure below provides a matrix to illustrate the monetary institutional goals with the sourcing approach of insourcing or outsourcing the physical campus bookstore.

For many institutions, however, outsourcing deals were signed before institutions gave much thought to digital course materials that required no warehousing, retail shelf space, or other typical strengths of physical stores. Some even gave “exclusive rights” for digital for more than a decade in exchange for payments to the university. These were not unusual deals as institutions often sell rights to advertise in their sports facilities, and institutional payments from the outsourcing deals may provide critical funds to pay for operations or valuable programs within an institution.

Yet… the point is clear. If publishers will sell to the students through an institution with an inclusive access or other bursar-billed model (and they will), a model without markup will yield a lower cost to students for the same materials than a model with an additional profit incentive. Since digital materials are dynamically provisioned for digital access when students add a course, there are fewer value-adding roles for physical bookstores even if they operate websites as an additional sales channel.

To illustrate, one 2018 eText deal for multiple institutions has this in its public announcement:

Thus, if a profit motive leads to added mark-up through campus bookstores or other middlemen in a digital transaction, an institution is overtly legitimizing a higher cost of attendance than could otherwise be achieved. The money received is a compelled transfer payment from students to bookstore owners and in all likelihood, with some revenue-sharing with the institution.

It is very important to distinguish bookstore and institutional profit sharing arrangements on non-compulsory sales from required, bursar-billed eTexts fees. Students have choices in where they buy new or used textbooks, sweatshirts, pencils, and coffee. It is an entirely different matter, however, if students are compelled to subsidize an economic model that is incapable of offering bursar-billed pricing at the same or better price than an institution could otherwise achieve for its students. The markup difference is a compelled and often not transparent transfer payment from students to somewhere.

What to Do?

Step one is to clarify an institution’s goals. Indiana University’s eTexts program has four clearly stated goals, including reducing the cost of course materials chosen by faculty. With the unwavering support of the IU administration and faculty, we have pursued not just reducing, but minimizing the cost of digital course materials. We do so by not adding a markup via middlemen in the program.

If an institution has a reason to need a transfer payment as a markup on each eText, then step two is to assess how that should be achieved. It could be done by adding $1-2 to each bursar-billed eText fee or through an outsourced bookstore arrangement that usually marks up based on a percentage then makes an aggregate payment to an institution. Both are credible means to achieve the same goal.

Once institutions are crystal clear on their goals with all the decision makers, they can then assess any opportunities or constraints for their choices of the “Four Paths” at the end of the section on publisher negotiations. The most frequent constraint is that an institution intentionally or unintentionally constrained its options with a bookstore outsourcing contract. I have heard many accounts from colleagues who fell under extreme pressure from an outsourced bookstore to continue or to give them exclusive rights and markups on digital course materials with some payment to the institution.

In the end, contracts have terms, negotiations, re-negotiations, and exit clauses, and each institution will need to assess who is really its customer and its goals for a campus bookstore.