4 Black Markets during World War II

—by Lauren Gronek

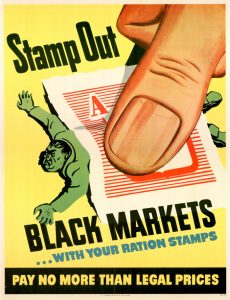

Government economic control produces lucrative results for underground markets. During World War II the United States instituted a rationing program that led to both underground markets and official efforts, including the use of propaganda, to curtail black market activity (see Figure 1: Stamp Out Black Markets). Created by the United States Office of Price Administration in 1943, the Stamp Out Black Markets poster demonstrates how U.S. rationing during World War II unintentionally spread black markets while the government used propaganda in an attempt to dissuade citizens from engaging in these illicit markets.

Figure [1]: Stamp Out Black Markets poster

Rationing resulted from a limited amount of goods in circulation during the war. The fighting created difficulties for certain traded goods to get to the United States. In some countries “capture of supply sources” [2] caused shortages. The Japanese took control of areas where factories and farms produced goods vital to the United States. This lack of trade with the axis-controlled countries wreaked havoc on American markets. In other areas like South America “German U-boats sank many U.S. merchant ships.” [3] On the other side of the world Germany created problems for United States trade. With the world in complete disarray and enemies on either side limiting trade, the U.S. had to find a solution to this economic problem.

American government stepped in to address the problems of high prices and shortages. The Office of Price Administration (OPA) was the specific government agency charged with combatting inflation resulting from shortages. The OPA chose to implement rationing. Its powers prevented “price spiraling, rising costs of living, profiteering, and inflation” along with “hoarding of materials and commodities.” [4] It ultimately “stimulat[ed] provision of the necessary supply of materials and commodities required for civilian use.” [5] The government claimed if rationing was not implemented, extreme inflation would choke citizens. A pamphlet explained inflation to citizens as “when people and businesses have more money to spend than there are things to spend it on, prices go up.” [6] Pamphlets like these informed citizens about the need for price ceilings. The federal government’s power expanded greatly to control prices and rations and aid the war effort on the home front.

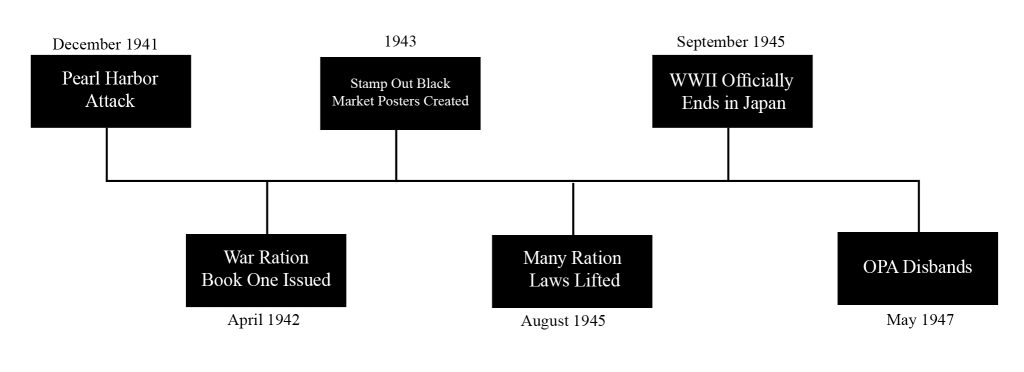

Figure 2. Timeline of Government and War events during World War II [7]

Figure 2. Timeline of Government and War events during World War II [7]

Unfortunately, dissatisfaction with the regulations gave the opportunity for black markets to flourish. As shown in Figure 2, the process of the ration system began in the spring of 1942. [7] Rations took form as “stamps from which were turned in to obtain specific food items and other necessities.” [8] An individual only purchased the contents of the stamp book for that week. The goal of rationing kept “people from overbuying and hoarding commodities” [9] so limited goods would be available to all. They also controlled prices to “ke[ep] your cost of living from getting out of hand.” [10] Using extreme governmental regulatory powers in rationing, the OPA intended for citizens to band together, help fight the war and promote a fair distribution of goods.

Yet, the newness of rationing meant constant change and complexity. The ration book and procedures changed around once every 4 months. [11] Shoppers dealt with the reality that, “the rationing system meant the mastery of a constantly changing system of point values in the papers.” [12] Sometimes a product would be taken off the ration list right as a new ration book came out resulting in confusion over what stamps in the book could be used. Because ration stamps did not count for actual money “the buyer had to surrender to the seller not only the (controlled) money price but also a stipulated amount of ration coupons or stamps (“points”).” [13] Double budgeting to account for the monetary price and the stamp value took time and effort on the parts of homemakers. Individuals underwent difficulties just to obtain meager portions of goods. In the hard times of war many disliked going through the hoops to budget their lives and railed against rationing and regulation.

Along with the distaste for the inconvenience of rationing, Americans unlimited desires for scarce goods spurred illicit markets. In a government commissioned video depicting a shady market transaction between a woman and a butcher, the woman claims, “I guess you have to pay to get what you want these days.” [14] This quote demonstrates how black markets spread. Humans have insatiable wants. According to psychologist, Robert Cialdini, when goods are scarce, individuals want the goods more. [15] Many citizens hated denying themselves to help the war cause. Despite the rhetoric and social pressures of sacrificing for the war cause, the self-centeredness of human nature often won out. The usual market where one easily obtained wanted commodities was hard to give up. Underhanded transactions to get more of what one wanted occurred everywhere and became normalized. The combination of these factors lead to the growth of several specific black markets.

Meat was one of the largest black markets during war time. According to the department of Agriculture “20 per cent of all meat found its way into the black market.” [16] In addition “90 per cent of all meat transactions at the wholesale and slaughterhouse level were in excess of legal ceilings.” [17] The meat operations largely occurred behind the scenes in legal firms. OPA leader Chester Bowles admitted “most of our activity is concerned with violations on the part of hitherto reputable individuals or firms.” [18] In a government video about black markets the narrator claims “the most common black market transactions were shabby little under-the-counter deals between butchers and their regular customers.” [19] The video depicts a woman asking for more meat than her ration stamps can afford, and then leaving when she cannot get what she wants. The butcher calls her back and offers her black market meat for above the price ceiling. Knowing the right people in businesses allowed for underhanded violations of price ceilings to perpetuate black market activity.

On top of legal fronts, cattle rustling and unregulated slaughtering added to the criminal activity in the meat industry. Black marketeers “would buy livestock for slaughter above the ceiling price and then sell it on to black-market distributors.” [20] In another government sponsored video, the story follows a court case “based off a composite of various cases uncovered by OPA investigator.” [21] Underhanded businessmen went to livestock auctions and outbid legal buyers to get the cattle then sell it to butchers. The slaughtering process fo r these illegal meat businesses were unsanitary and underground. [22] An essential part of the American diet, meat remained an intensely desired good. The black market for meat showed how luxury goods were worth bending the rules.

Another large black market was one for gasoline. Due to need on the warfront, gasoline was in high demand and low supply. In addition, rubber was in low supply due to Japanese control of eastern rubber plantations. In response “rationing gasoline,…would conserve rubber by reducing the number of miles Americans drove.” [23] This combination caused strong demand for illegal means of obtaining gas. These markets took form through “experienced criminal rings,” and “dr[ew] teen-age youngsters into its operations in dangerous numbers.” [24] While meat markets operated under legal guises, criminals dominated the illicit gasoline industry. Counterfeit and stolen coupons circulated. The OPA estimated 5% of sales from fake gasoline stamps. [25] Another study “estimated that 8% of oil was purchased illegally.” [26] In other cases, truckers reported having less gas than they actually had to receive extra stamps for illegal sale [27]. The government attributed this kind of activity to “the assistance of careless or dishonest retail gasoline dealers.” [28] The gas black market was a group effort between retailers, buyers, and criminals.

Black market gasoline became the norm. In journalist Mark Miller’s article, he describes how he “finagled” his way driving across America without using a single ration stamp. He simply talked to clerks at the stations until they allowed him to purchase gas without a ration stamp. [29] Obviously, rationing was not taken seriously if obtaining gasoline without stamps was so easy. Widespread acceptance of illegal markets allowed easy access to the goods. Being a necessity to the comfortable living of Americans, this black market flourished without much regret of those involved.

Undoubtedly, enforcement of regulation skyrocketed higher than ever during the war. Despite its small numbers, the OPA dedicated itself to carrying out sanctions to violators of ration and price ceiling laws. The OPA enforced actions against 280,724 violators of rationing and price laws throughout the years of the war. [30] Penalties went as far as one year in prison and a five thousand dollar fine. [31] The strictness of the laws were equalled by their enforcement measures. Surprisingly, “One in fifteen businesses—wholesale, retail, service and so on—was charged with illicit transactions.” [32] The OPA did not sit around. They actively enforced their stringent laws in attempts to control the wartime economy.

Yet, if their work was completely successful, posters like the Stamp Out Black Markets one would not exist. Historian Hugh Rockoff commented on the difficulty to pin down black markets and explained how their ever presence despite the high controls, “testifie[d] to the ubiquity of evasion.” [33] The government realized the stubborn nature of illicit markets and turned to the use of propaganda to fight them.

Propaganda techniques reflected government effort to keep control of the American economy in response to the black market backlash. Technological advance caused the birth of advertising. Advertisers understood the ways in which visual graphics, color, and sensational language affected an audience. During World War II, these techniques, used in propaganda posters, had a large effect on viewers across the world. The use of propaganda proved effective in the case of Nazi Germany where Hitler claimed, “Propaganda works on the general public from the standpoint of an idea and makes them ripe for the victory of this idea.” [34] The specific use of stark imagery and word aided the Nazis to bring the whole population in agreement with their “idea” against the Jewish people. This trend continued in American culture but was used in an attempt to promote good behavior. When the black market problem arose, the U.S. Government regrouped by disseminating effective visual posters to sway the audience in the intended direction. The Office on War Information, a government commissioned group, created and spread propaganda to the masses. Posters like the Stamp Out Black Markets one came into circulation hoping attractive and sensational posters would dissuade illicit transactions.

This poster utilizes tactics of moral expectation along with bright colors to attract the attention of viewers. In Edward Bernays’ Propaganda, the opening sentence states, “the conscious and intelligent manipulation of the organized habits and opinions of the masses is an important element in democratic society.” [35] The posters reflects Bernays’ statement because each element is purposefully used to invoke a specific response in the audience. The angry green man symbolizing the black market is flattened out and frowning in protest yet doing little to resist. This gives the viewer a feeling of ease that the large thumb possesses the capabilities to permanently squash criminal market behaviors. The heading reading “Stamp Out Black Markets” makes use of clever language to generate agreeability within the audience. These visual elements served to manipulate society in a democratic manner as Bernays stated.

The general rhetoric around United States World War II propaganda involved doing what was morally right to help the good of the soldiers fighting overseas. The posters intended to make citizens feel unpatriotic and selfish if not following the rules of rationing. This brings to light Cialdini’s social proof principle of doing what was expected because everyone else did so as well. [36] By portraying the black marketeer as a frowned-upon character, one feared they would be viewed this way by others if discovered engaging in underhanded businesses. Widespread use of persuasive propaganda gave the government the solution they thought would solve the black market problem.

Agencies voiced confidence in their programs’ effectiveness in combatting markets through enforcement of laws and poster campaigns. Yet, with the stubbornness of black markets, the question of the true effectiveness of this poster is raised. According to Patrick Carr, the chief investigator of the Massachusetts OPA office, 96% of the cases brought to court for alleged black market activities won in favor of the OPA. [37] But does a percentage of winning cases really show the breadth of work this agency accomplished? Although a high success rate, the cases won were possibly very obvious and did not require much work on the OPA’s part. In contrast to the cases won, the black markets spanned the whole country and reached goods from food to gasoline. Carr even stated that “we have less than 3000 OPA investigators in the entire country… and these men have the responsibility of looking over two million wholesalers and retailers…” [38] With such a large population to monitor, black markets slipped through the cracks. The staged confidence in the OPA shown in propaganda disputed the deep-rooted reality of illicit markets.

The end of World War II black markets shows how consumers find and stick to the cheapest and easiest options. Rationing was lifted fully within a year of the war’s end. [39] The OPA disbanded. With the end of the OPA came the end of the propaganda posters related to black markets. Individuals mostly returned to buying gas and meat legally and the American economy slowly restored. Yet, the normalized culture of underhanded dealings and propaganda stuck with Americans. Individuals no longer needed to buy rationed items underground; but, the fostered disregard for the laws surrounding illegal businesses allowed many to enter into other markets with little moral concern.

During a time of increased powers the United States government unintentionally fostered black markets. Propaganda and rationing was derived from good intentions. Yet, the moral purpose of the laws did not always show up in the behaviors of citizens. Propaganda use shows governments’ manipulation of media to influence the minds of the public. Although the posters aided the argument of the government, black markets still operated through citizens who required the goods normally enjoyed in peace times. Unfortunately, the cost of regulation resulted in underhanded dealings that rebelled against the expectations of patriotism. These wartime markets led to a normalized culture of illicit markets that is still seen in our society today. The propaganda poster examined in this essay represents the eternal conflict over whether regulation causes or mends black markets in the United States.

Endnotes

1. Figure 1. “Stamp out black markets.” United States Office of Price Administration, Washington, D.C., 1943.

2. Higgs, Robert. “The Two-Price System: U.S. Rationing During World War II.” FEE. April 24, 2009. https://fee.org/articles/the-two-price-system-us-rationing-during-world-war-ii/. 16 Oct. 2018.

3. Higgs, Robert. “The Two-Price System.”

4. Franklin D. Roosevelt: “Executive Order 8734 Establishing the Office of Price

Administration and Civilian Supply.,” April 11, 1941. Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project. http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/? pid=16099. 15 Oct. 2018.

5. Franklin D. Roosevelt: “Executive Order 8734 Establishing the Office of Price

Administration and Civilian Supply.”

6. “Double Trouble: What to Do about Inflation and Deflation”. Boston, Massachusetts: Public ity Files, Information Division, 1945.

7. Figure 2. “Timeline Of Government and War events during World War II (“World War II Rationing on the U.S. Homefront.” World War II Rationing on the U.S. Homefront | Ames Historical Society, www.ameshistory.org/content/world-war-ii- rationing-us-homefront., “Stamp out black markets” United States Office of Price Administration. Washington, D.C., 1943., Tally D. Fugate, “Rationing,” The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture, www.okhistory.org)

8. LoProto, Mark. “World War II and Rationing in the US.” Visit Pearl Harbor. April 18, 2018. https://visitpearlharbor.org/wartime-rationing-in-the-us/. 16 Oct. 2018.

9. LoProto, Mark. “World War II and Rationing in the US.”

10. Bresnahan, Lawrence J. “Talking about Ration Book Four.” Interview. Station WHDH. Octo ber 20, 1943.

11. Bresnahan, Lawrence J. “Talking about Ration Book Four.”

12. Lingeman, Richard R. Don’t You Know Theres a War On?: The American Home Front, 1941-1945. New York: Thunders Mouth Press/Nation Books, 2003.

13. Higgs, Robert. “The Two-Price System.”

14. “Growth of the Black Market During WW2.” YouTube. December 01, 2015. https://www.y outube.com/watch?v=5o36EhTYBzM. 16 Oct. 2018.

15. Cialdini, Robert B. Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion. New York, NY: Collins, 1984.

16. Lingeman, Richard R. “Remembrance of Rationing past.” The New York Times. September 09, 1973. https://www.nytimes.com/1973/09/09/archives/remembrance-of-rationing-past- a-stickers-b-stickers-red-stamps-and.html. 16 Oct. 2018.

17. Lingeman, Richard R. “Remembrance of Rationing past.”

18. Lingeman, Richard R. “Remembrance of Rationing past.”

19. “Growth of the Black Market During WW2.”

20. Clinard, Marshall B. The Black Market ; a Study of White Collar Crime ; Reprinted with a New Preface. Montclair, NJ: Patterson Smith, 1972.

21. ”Black Marketing ~ 1944 US Office of War Information; Black Market in WWII USA.” YouTube. June 04, 2017. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WbI0rGHFOP0. 16 Oct. 2018.

22. “Growth of the Black Market During WW2.”

23. “Seventeen States Put Gasoline Rationing into Effect.” History.com. November 13, 2009. https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/seventeen-states-put-gasoline-rationing-into- effect. 16 Oct. 2018.

24. “Facts You Should Know” Statement No. 3, Office of Price Administration, Nov. 1943.

25. “Facts You Should Know.”

26. Maxwell, James A., and Margaret N. Balcom. “Gasoline Rationing in the United States, II.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 61, no. 1 (1946): 125.

27. “Facts You Should Know.”

28. “Facts You Should Know.”

29. Miller, Mark. “Border to Border on Bootleg Gas.” Collier’s Weekly, October 2, 1943.

30. Taylor, Robert L. “Enforcement of Price and Rent Controls.” CQ Researcher by CQ Press. April 5, 1951. https://library.cqpress.com/cqresearcher/document.php?id=cqresr re1951042500. 16 Oct. 2018.

31. Taylor, Robert L. “Enforcement of Price and Rent Controls.”

32. Lingeman, Richard R. Don’t You Know Theres a War On?.

33. Lingeman, Richard R. Don’t You Know Theres a War On?.

34. Rockoff, Hugh. Drastic Measures: A History of Wage and Price Controls in the United States. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

35. Hitler, Adolf. Mein Kampf. Hurst and Blackett, 1942.

36. Bernays, Edward. Propaganda. Melusina, 2010.

37. Carr, Patrick. “Talking About Black Markets.” Interview. Station WORL. December 5, 1943.

38. Carr, Patrick. “Talking About Black Markets.”

39. Figure 2. “Timeline.”

Bibliography

Bernays, Edward. Propaganda. Melusina, 2010.

”Black Marketing ~ 1944 US Office of War Information; Black Market in WWII USA.” YouTube. June 04, 2017. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WbI0rGHFOP0. 16 Oct. 2018.

Bresnahan, Lawrence J. “Talking about Ration Book Four.” Interview. Station WHDH. October 20, 1943.

Carr, Patrick. “Talking About Black Markets.” Interview. Station WORL. December 5, 1943.

Cialdini, Robert B. Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion. New York, NY: Collins, 1984.

Clinard, Marshall B. The Black Market ; a Study of White Collar Crime ; Reprinted with a New Preface. Montclair, NJ: Patterson Smith, 1972.

“Double Trouble: What to Do about Inflation and Deflation”. Boston, Massachusetts: Public ity Files, Information Division, 1945.

“Facts You Should Know” Statement No. 3, Office of Price Administration, Nov. 1943.

Franklin D. Roosevelt: “Executive Order 8734 Establishing the Office of Price

Administration and Civilian Supply.,” April 11, 1941. Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project. http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/? pid=16099. 15 Oct. 2018.

Fugate, Tally D., “Rationing,” The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture, www.okhistory.org. Accessed 16 Oct. 2018.

“Growth of the Black Market During WW2.” YouTube. December 01, 2015. https://www.y outube.com/watch?v=5o36EhTYBzM. 16 Oct. 2018.

Higgs, Robert. “The Two-Price System: U.S. Rationing During World War II.” FEE. April 24, 2009. https://fee.org/articles/the-two-price-system-us-rationing-during-world-war-ii/. 16 Oct. 2018.

Hitler, Adolf. Mein Kampf. Hurst and Blackett, 1942.

Lingeman, Richard R. Don’t You Know Theres a War On?: The American Home Front, 1941-1945. New York: Thunders Mouth Press/Nation Books, 2003.

Lingeman, Richard R. “Remembrance of Rationing past.” The New York Times. September 09, 1973. https://www.nytimes.com/1973/09/09/archives/remembrance-of-rationing-past- a-stickers-b-stickers-red-stamps-and.html. 16 Oct. 2018.

LoProto, Mark. “World War II and Rationing in the US.” Visit Pearl Harbor. April 18, 2018. https://visitpearlharbor.org/wartime-rationing-in-the-us/. 16 Oct. 2018.

Maxwell, James A., and Margaret N. Balcom. “Gasoline Rationing in the United States, II.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 61, no. 1 (1946): 125.

Miller, Mark. “Border to Border on Bootleg Gas.” Collier’s Weekly, October 2, 1943.

Rockoff, Hugh. Drastic Measures: A History of Wage and Price Controls in the United States. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

“Seventeen States Put Gasoline Rationing into Effect.” History.com. November 13, 2009. https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/seventeen-states-put-gasoline-rationing-into- effect. 16 Oct. 2018.

“Stamp out black markets.” United States Office of Price Administration, Washington, D.C., 1943.

Taylor, Robert L. “Enforcement of Price and Rent Controls.” CQ Researcher by CQ Press. April 5, 1951. https://library.cqpress.com/cqresearcher/document.php?id=cqresr re1951042500. 16 Oct. 2018.

“World War II Rationing on the U.S. Homefront.” World War II Rationing on the U.S. Homefront | Ames Historical Society, www.ameshistory.org/content/world-war-ii- rationing-us-homefront.