8 How the Honey Mafia Stuck

-by Caroline Anders

Black markets victimize millions worldwide. They exist in the crevices of society, sometimes at its sinister edges; sometimes in plain view, masked by the world’s cluelessness. As proof, look no further than to the “bee rustlers,” those who steal honeybees and their hives for profit. The name comes from the concept of cattle rustlers, thieves who steal cows when they’re run on ranges far from their ranchers. Bee rustlers capitalize on that same trust beekeepers exercise by keeping their hives in unguarded fields. The honeybee population took a nosedive over the past decade, making the bees’ honey-making and pollinating skills even more precious to average citizens than they know. Thus, the bee black market was born. Adept criminals load hives onto trucks in the dead of night, stealing not only the bees but also their highly-profitable skills. The strange, underground world of bee thieves and heroes will live on as long as colonies continue to collapse and the value of the winged creatures continues to rise.

In 2007, beekeepers nationwide began reporting a worrying loss of hives. The epidemic was quickly named Colony Collapse Disorder (CCD) and experts began searching for answers. They still haven’t found them.[1] Winter losses have averaged around 30 percent each year since 2006.[2] The bee-fueled economy collapsed. Bees not only produce honey and six other products available for sale — beeswax, pollen, royal jelly, propolis, hives and venom — but also champion the often-forgotten pollination industry.

Upon discovering how pollination leads to more abundant harvests, farmers worldwide began to lean more heavily on pollinators to increase their yields. Worldwide, pollinators contribute nearly $245 billion to the total value of global agricultural exports.[3] Between 1961 and 2006, it is estimated that dependency on pollinators increased 56 percent.[4] In the United States alone, pollination services are valued at $16 billion annually. As demand grew for crops like almonds, pistachios and mandarin oranges in that time, so did demand for bees. Pollination has actually outranked honey as the most lucrative bee-related industry in the nation.[5] Though both honey and pollination demand are on the rise, the number of honeybee colonies is still sinking thanks to CCD.[6]

As beekeepers nationwide experience colony loss, they try to solve the issue by splitting their bee kingdoms to build new hives or replenish them with purchased bees.[7] This is no small task since it is nearly impossible to detect CCD until it is too late. Some desperate apiarists try to keep their healthy bees away from sick colonies to prevent collapse and contagion.[8] Many, however, simply exit the market. Those who choose to stay have a tough road ahead of them. The illicit side of the bee world then rears its ugly head.

According to the apiarist community, most bee thieves are actually just washed-up beekeepers making a last-ditch effort to save their businesses. When someone stole 300 of Randy Verhoek’s colonies in the winter of 2017, he called it an inside job.[9] According to reporting from Texas Monthly, many commercial beekeepers believe Verhoek’s contention.[10] The working theory of bee thievery is that inexperienced beekeepers enter the market, make promises to customers they can’t keep, and then don’t know what to do when their colonies die. They panic, and then they steal.

The theory, though, really isn’t a theory at all. In 1977, rogue, 23-year-old beekeeper David Allred was sentenced to more than six years in prison for the theft of $10,000 worth of hives from another beekeeper in Tracy, California, when his hives began failing.[11] Prosecutors also found him guilty of helping to poison 600 of a competitor’s hives and stealing 400 hives in 1972.[12] According to the Los Angeles Times, Allred told the court at the time of his sentencing that he wanted to be remembered as the “Jesse James of the beehive industry.” Allred didn’t stop at his first heist, though. He stole 150 more hives in 2013, earning himself the brand of the “most notorious beenapper in history.”[13] Viktor Zhdamirov, who stole 80 hives from Tauzer Apiaries and mixed the colonies with his own, also serves as a perfect example of the beekeeper down on his luck who turns to illicit activity. Beekeeper Mark Tauzer told Modern Farmer this circular chain of bee theft goes against everything the industry stands for.[14] “Most people go into beekeeping because they love bees,“ he said. “You don’t hurt the bees.”

David Bradshaw, a lifelong beekeeper in San Joaquin Valley, California, told investigative reporting outlet Reveal that commercial beekeeping, however, is still “death by a thousand cuts.”[15] With bees dying at an alarming rate, each harvest is a delicate game of how far the colonies can be pushed. That only intensified when bee rustlers came into the picture.

David Bradshaw, a lifelong beekeeper in San Joaquin Valley, California, told investigative reporting outlet Reveal that commercial beekeeping, however, is still “death by a thousand cuts.”[15] With bees dying at an alarming rate, each harvest is a delicate game of how far the colonies can be pushed. That only intensified when bee rustlers came into the picture.

The phenomenon makes sense, too. If bees are so fragile to begin with, any old thief wouldn’t be able to keep them alive — completely undermining the goal of stealing them in the first place. These bandits have to have some level of skill with the insects, which generally means they’re apiarists themselves. According to the Dictionary of Occupational Titles, becoming a beekeeper takes between two and four years.[16] The black market for bees is most easily explained once the reader understands the commercial bee industry. Commercial bees are constantly on the move — no longer the stationary livestock they once were. Beekeepers nationwide truck their colonies around to pollinate fields across the country. Martinsville, Indiana beekeeper Tracy Hunter takes his bees to work Florida’s oranges in the fall, California’s almonds in the winter and Michigan’s blueberries in the spring.[17] He loads his hives onto semi-trucks in groups of hundreds, preparing for the perpetual bee road trip that so many beekeepers set out on. Hunter is worried about his bees this winter. He’s sending about 500 hives to California, which he says is a hotbed for bee rustlers.[18]

- Bottles of clover and wildflower honey sit on display at the Bloomington Farmers Market. Tracy’s wife, Christina Hunter said she prefers lighter honeys like thee for things like baking bread or stirring into tea.

- Tracy Hunter explains the life cycle of a honeybee. Hunter caught his first swarm with his grandfather when he was 14 years old.

- Bees cluster in a display hive in the Hunter Honey Farm’s gift shop. Despite popular belief that the queen bee is the hive’s only female, all worker bees are female as well.

Demand for California’s almonds recently hit an all-time high. The state’s trees alone produce over 2 billion pounds of the nut each year, and almond growers pay top-dollar for pollination services.[19] Twenty-five thousand semi-trucks would be needed to carry that many almonds, and that many trucks lined up bumper-to-bumper could stretch from Bloomington, Indiana past Milwaukee, Wisconsin and into Lake Michigan. The cost of pollinating an almond field has been on the rise since 2005, partly due to the increased demand for the nut.[20] Each farmer needs at least two bee colonies per acre of crops per season, which means the pollination industry is increasingly lucrative. In 2016, almond farmers were paying about $180 per hive of the pollinators.[21] In an in-depth investigation into bee rustling, Reveal found that almond-pollinating hive value is at a record high.[22] This is good news for beekeepers, but it also makes California a hotbed for bee theft.

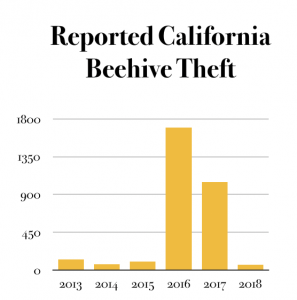

From 2016 to 2017, more than 2,700 hives were reported stolen in California.[23] Each hive is home to one colony, and each colony produces an average of 55.3 pounds of honey per season.[24] 2,700 stolen hives would produce about 149,310 pounds of black market honey — enough to fill about 250 bathtubs to the brim.[25] All of the honey produced in the U.S. in 2016 would fill about 20 and a half Olympic-sized swimming pools. Most hives are stolen at the front of almond season, snatched at the moment when apiarists have put the most time and money into raising the bees to be strong. When Joe Romance lost a few hundred hives in January 2015, he was out about $50,000.[26] Bee theft is no petty crime.

Law enforcement has a tough task on its hands when dealing with potentially stolen hives.[27] Without proper markings, it can be nearly impossible for police to discover who the hives really belong to and how they got into the hands of the accused thieves. In the case of 180 bee boxes stolen from Joe Romance, a beekeeper outside Bakersfield, California, Romance tracked down the men who stole his property without the help of the police.[28] He and some friends set up a sting to trap the thieves by having a friend pose as an almond farmer willing to pay top-dollar to rent some hives. Romance’s undercover team convinced the thieves to let them view their hives, where they located Romance’s distinctive mark on the side of the bee boxes. Those marks gave police probable cause to make an arrest. Yolo County Deputy District Attorney Martha Holzapfel, who prosecuted this case, said law enforcement needs to understand bee rustling more thoroughly before it can fully grapple with how to fight it. Police departments in high-risk areas are encouraging beekeepers to emblazon their hives with distinctive markings — just in case.[29]

Bee rustling is a unique black market because of how self-contained it is. As aforementioned, bee rustlers almost certainly have to be beekeepers themselves, or the whole industry wouldn’t make sense. Dead bees can’t make money, and keeping bees alive is no easy task. It is difficult to think of another illicit market so thoroughly wrapped up in itself. Most other industries have so few barriers to entry that they could be lucrative to anyone. Black market bees are born out of fear. The fear of failure, the fear of losing money, but primarily the fear of losing millions of bee lives.

As long as the need for pollination continues to climb and the number of bees continues to fall, bee rustlers will keep cropping up across America. Beekeepers will keep forming vigilante groups to protect against them, some will even attach GPS locators to their hives, and others will simply be run out of business by the thieves.[30] The irony of this runs deep since the thieves are trying to stay on their feet by running their competitors out of business. This, however, is not unique to the bee industry. As Misha Glenny argued in his book McMafia, black markets flourish when desperation is involved.[31] Desperate people do desperate things. This isn’t just an American phenomenon, either. Bee rustlers exist globally, from New Zealand to the UK.[32] The thieves have been branded the “Honey Mafia” in some circles.

The rise of the Honey Mafia begs one more important question: who’s buying this honey? Though this black market is not widely understood, there are surely consumers who know they may be using dirty honey. That said, this doesn’t matter in many other illicit markets and may have no standing at all on a person’s willingness to make a purchase.[33] Things get especially sticky since consumers must accept that measuring how much honey is produced by stolen bees is next to impossible, since the bees often mix with other hives and there’s no way to detect where most honey came from. In that way, the deviant economy created by bee rustlers is wholly dependent on the licit economy, just as Gilman argued in “Deviant Globalization: Black Market Economy in the 21st Century.”

The intersection of these licit and illicit economies is so interesting because scholars and beekeepers alike cannot disentangle the two. Selling fraudulent honey is the perfect crime — if the thief can take the hives without any issue. Dirty honey is one of the markets so engrained in people’s everyday lives — an estimated one in every three bites of food was made possible by pollinators like honeybees — that it is easy to forget and even easier to ignore.[34] Turning the other cheek to bad honey is seemingly a lot more innocuous than looking the other way during a heroin deal.

When times got tough for the beekeeping community, it folded in on itself. Whether that trend will continue is anyone’s guess. Just like in all other industries, difficult conditions create a hotbed for illegal activity, and it doesn’t look like things are going to get any easier for beekeepers any time soon. Despite extensive research on CCD, experts don’t know how to stop these insect-scale apocalypses. Despite efforts to keep colonies healthy, more drop off every day. As honey gets more and more precious, bee thievery will continue to bloat. It is simply the market reacting to a demand increase. The change is inevitable, but the harms are neatly tucked out of sight. The victims of these crimes are not the millions of honeybees displaced from their hives and homes, they’re the struggling beekeepers being back-stabbed by their own community. They’re the consumers unknowingly plucking bear-shaped jars of tarnished honey off of shelves. Black markets don’t have to have sinister names to do ugly work. In the bee world, in the Honey Mafia, it is always an inside job.

Bibliography

“Bees.” Ag Marketing Resource Center.

“BEEKEEPER (Agriculture) Alternate Titles: Apiarist; Bee Farmer; Bee Raiser; Bee Rancher.” Dictionary of Occupational Titles, Photius Coutsoukis, 1981,

Boissoneault, Lorraine. “The Sting.” Fighting the Rise of Bee Rustlers, 7 Jan. 2015.

Burgett, M . 2011. Pacific Northwest honey bee pollination economics survey 2010. Natl. Honey Rep . 30: 11–18.

Calderone, N. W . 2012. Insect pollinated crops, insect pollinators and US agriculture: trend analysis of aggregate data for the period 1992-2009. Plos One . 7: e37235.

Duncan, Byard. “California’s Almond Harvest Has Created a Golden Opportunity for Bee Thieves.” Reveal, 6 Oct. 2018.

Elsasser, Brian. “Farm Crime: To Catch a Bee Rustler.” Modern Farmer, 11 May 2016.

Fitzpatrick, Craig. “New Zealand’s Black Market for Honey Bees.” newstalk.com.

Gallai, N., J.Salles, J.Settele, and B. E.Vaissiere. 2009. Economic valuation of the vulnerability of world agriculture confronted with pollinator decline. Ecological Econ . 68: 810–821.

Gilman, Nils, et al. Deviant Globalization: Black Market Economy in the 21st Century. Continuum, 2011.

GLENNY, MISHA. MCMAFIA. HOUSE OF ANANSI PRESS, 2018.

Hunter, Tracy. “On Bees.” 18 Sept. 2018.

IFAS. “Colony Collapse Disorder.” UF/IFAS Extension, University of Florida, 25 June 2018.

“Jury Convicts West Sacramento Bee Thief.” Yolo County District Attorney, Yolo County, 21 Feb. 2014.

Klein, A. M., B. E.Vaissière, J. H.Cane, I.Steffan-Dewenter, S. A.Cunningham, C.Kremen, and T.Tscharntke. 2007. Importance of pollinators in changing landscapes for world crops. Proc. Biol. Sci . 274: 303–313.

Oldroyd BP (2007) What’s Killing American Honey Bees?. PLOS Biology 5(6): e168.

Oyeniyi, Doyin. “Forget Cattle Rustling-Watch Out For Bee Rustlers.” Texas Monthly, Texas Monthly, 11 Jan. 2017.

Redden, Molly, et al. “Meet California’s Most Notorious Beenapper.” Mother Jones, 24 June 2017.

Ritten, Peck, Ehmke, Patalee; Firm Efficiency and Returns-to-Scale in the Honey Bee Pollination Services Industry, Journal of Economic Entomology, Volume 111, Issue 3, 28 May 2018, Pages 1014–1022.

Suryanarayanan, S . 2012. Be(e)coming experts: the controversy over insecticides in the honeybee colony collapse disorder. Soc. Stud. Sci . 43: 215–240.

USDA. “Honey.” National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS), Agricultural Statistics Board, 14 Mar. 2018.

United States Department of Agriculture . 2016. USDA releases results of new survey on honeybee colony health. Release No. 0114.16.

vanEngelsdorp D, Traynor KS, Andree M, Lichtenberg EM, Chen Y, et al. (2017) Colony Collapse Disorder (CCD) and bee age impact honey bee pathophysiology. PLOS ONE 12(7): e0179535.

Ward, R., A.Whyte, and A.James. 2010. A tale of two bees: looking at pollination fees for almonds and sweet cherries. Am. Entomol . 56: 170–177.

Yang, Sarah. “Pollinators Help One-Third of World’s Crop Production, Says New Study.” UC Berkeley, 25 Oct. 2006.

- BP Oldroyd (2007) What's Killing American Honey Bees?. PLOS Biology 5(6): e168. ↵

- D vanEngelsdorp, KS Traynor, M Andree, EM Lichtenberg, Y Chen, et al. (2017) Colony Collapse Disorder (CCD) and bee age impact honey bee pathophysiology. PLOS ONE 12(7): e0179535. ↵

- N Gallai, J.Salles, J.Settele, and B. E.Vaissiere. 2009. Economic valuation of the vulnerability of world agriculture confronted with pollinator decline. Ecological Econ . 68: 810–821. ↵

- A Klein, BE Vaissière, J. H.Cane, I.Steffan-Dewenter, S. A.Cunningham, C.Kremen, and T.Tscharntke. 2007. Importance of pollinators in changing landscapes for world crops. Proc. Biol. Sci . 274: 303–313. ↵

- S Suryanarayanan, 2012. Be(e)coming experts: the controversy over insecticides in the honeybee colony collapse disorder. Soc. Stud. Sci . 43: 215–240. ↵

- United States Department of Agriculture . 2016. USDA releases results of new survey on honeybee colony health. Release No. 0114.16. ↵

- Ibid. 2 ↵

- IFAS. “Colony Collapse Disorder.” UF/IFAS Extension, University of Florida, 25 June 2018. ↵

- Doyin Oyeniyi, “Forget Cattle Rustling-Watch Out For Bee Rustlers.” Texas Monthly, Texas Monthly, 11 Jan. 2017. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Molly Redden, et al. “Meet California's Most Notorious Beenapper.” Mother Jones, 24 June 2017. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Brian Elsasser. “Farm Crime: To Catch a Bee Rustler.” Modern Farmer, 11 May 2016. ↵

- Byard Duncan. “California's Almond Harvest Has Created a Golden Opportunity for Bee Thieves.” Reveal, 6 Oct. 2018. ↵

- “BEEKEEPER (Agriculture) Alternate Titles: Apiarist; Bee Farmer; Bee Raiser; Bee Rancher; .” Dictionary of Occupational Titles, Photius Coutsoukis, 1981, ↵

- Hunter, Tracy. “On Bees.” 18 Sept. 2018. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- M Burgett, 2011. Pacific Northwest honey bee pollination economics survey 2010. Natl. Honey Rep . 30: 11–18. ↵

- R Ward, A.Whyte, and A.James. 2010. A tale of two bees: looking at pollination fees for almonds and sweet cherries. Am. Entomol . 56: 170–177. ↵

- R Ward, A.Whyte, and A.James. 2010. A tale of two bees: looking at pollination fees for almonds and sweet cherries. Am. Entomol . 56: 170–177. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- USDA. “Honey.” National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS), Agricultural Statistics Board, 14 Mar. 2018. ↵

- “Bees.” Ag Marketing Resource Center. ↵

- Lorraine Boissoneault, “The Sting.” Fighting the Rise of Bee Rustlers, 7 Jan. 2015. ↵

- Ibid. 15 ↵

- Ibid. 14 ↵

- Ibid. 9 ↵

- Ritten, Peck, Ehmke, Patalee; Firm Efficiency and Returns-to-Scale in the Honey Bee Pollination Services Industry, Journal of Economic Entomology, Volume 111, Issue 3, 28 May 2018, Pages 1014–1022. ↵

- MISHA GLENNY, MCMAFIA. HOUSE OF ANANSI PRESS, 2018. ↵

- Craig Fitzpatrick, “New Zealand's Black Market for Honey Bees.” newstalk.com. ↵

- Nils Gilman, et al. Deviant Globalization: Black Market Economy in the 21st Century. Continuum, 2011. ↵

- Sarah Yang, “Pollinators Help One-Third of World's Crop Production, Says New Study.” UC Berkeley, 25 Oct. 2006. ↵