3 Social Media and Its Impact on the Illicit Drug Market

-by Brianna Baughman

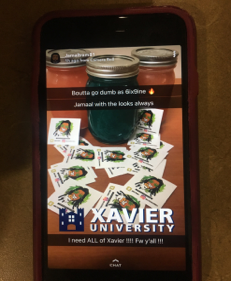

As I scrolled through my social media accounts, liking people’s Instagram photos, and watching my friend’s Snapchat stories, I came to Jamaal’s story and saw that he had another batch of edibles for sale. I thought nothing of it and continued going through everyone’s stories, clicking through Luke promising the highest quality weed in Indiana, and CJ insisting he’d have more product soon. None of these people are my close friends; I added them on Snapchat because they were friends of my friends, people I met only briefly, if at all. Despite this, they seem to think nothing of advertising their involvement in an illicit market on a social media platform where most of their viewers are likely distanced from them, much as I am.

Evan Spiegel and Bobby Murphy created Snapchat to allow friends to instantly share moments with each other through the use of individual threads of photos that can be seen for up to ten seconds each, or through stories that could be viewed numerous times by all of an individual’s friends for 24 hours.[i] Kevin Systrom created Instagram for individuals to share momentous events with family and friends, in the form of a picture or two and a written caption, and to connect users internationally through common interests such as baking or running.[ii] Despite this intention, social media has proven itself capable of doing much more than connect friends. “Several studies have argued that the dramatic increase in U.S. substance abuse admissions for prescription drugs… may partially stem from wider online availability of these drugs.”[iii] The prevalence of social media impacts the illicit market for drugs by making it safer for dealers, but potentially more dangerous for users, normalizing substance use, increasing ease of purchasing, and changing the way law enforcement must gather evidence on participants in the illicit drug market.

The launch of commonly used social media sites correlates with changes in drug abuse trends. The first social media site used in the United States, the website “Six Degrees,” was created in 1997 as a type of blogging site where users could follow their friends and connect with people even if those people weren’t near them.[iv] This introduction of social media, which was followed by the addition of other, more extensively used sites such as Twitter in 2006 and Instagram in 2010, correlates with a 500% increase in hospitalization as a result of drug overdose between 1997 and 2011.[v] Facebook became public in 2004[vi], the same year that the United States saw the highest level of drug overdose since 1979.[vii] In 2013, the same year that Snapchat added stories to the app[viii], the National Institute for Drug Abuse reported over an 8% increase in Marijuana use since 2002.[ix] This correlation between growth in the use of social media and growth in drug overdose suggests the severity of social media’s impact on drug use.

Twitter, Instagram, Facebook, and Snapchat condition their users to view drug use casually. Social media users encounter friends, acquaintances, and strangers using or producing illicit substances with astonishing frequency. This leads to a generally blasé attitude surrounding such activities.

While normalization can be seen in nearly all aspects of life, and is part of why humans are so adaptive, black markets also benefit greatly from it. Normalizing illicit activity eliminates any possible moral objections. The influence of language choice and repeated exposure, changes perceptions, allowing almost anything to appear normal,[x] and social media influences its users’ views regarding illicit markets through both of these methods. The emojis and to-the-point phrases used in place of lengthy pitches for social media advertisements give illicit substances the appearance of being at a juxtaposition with the seriousness of other products. Captions such as “#smokesession #SmokeLikeAGangsta #🌲💯🌲💯🌲💯,” seen in Figures 1 and 2, and posts of people smoking weed frame illicit drugs as lighthearted fun rather than as substances with possibly dangerous side effects.

Twitter users often tweet pictures of their Halloween costumes which can promote marijuana use as a laughably fun pastime, such as in the case of @Chanco78 in Figure 3 who, in 2018, dressed as a bong. Some dealers even repurpose their Snapchat bitmojis into stickers, seen in Figure 4, that can then be placed on every products for easy, sticky, and familiar marketing.

The repetition of such advertisement increases its potency. The average Instagram user spends 53 minutes a day on the app, and the average Snapchat user spends 49.5 minutes a day on the app.[xi] This app-usage leaves a lot of time for viewing the advertisement of illicit goods and sets up the perfect conditions for the repetitive exposure linked to normalization. The damaging illusion then ensues that everyone smokes weed, so those who don’t are the ones going against the norm. “[D]rugs – predominantly cannabis, but also LSD, amphetamines and ecstasy – are now accepted as a leisure activity, rather than being an act of rebellion.”[xii] The hashtag “#smokesession” was used on 131,000 posts as of November 7, 2018. Social media, with the help of the frequency with which its average user is active, portrays drug use in a casual light, thus normalizing it.

Social media, by definition, presents a platform for interaction without the need for face-to-face contact. Arranging drug deals through social media platforms gives suppliers the power to be picky about who they will sell to. Suppliers vet their customers before ever interacting face to face, so customers don’t necessarily know the name, appearance, or whereabouts of their supplier.[xiii] This anonymity means no accusatory fingers can be pointed until after the dealer decides the chances of being incriminated are low.

The repercussions change when advertisement is largely online and not connected to one’s person. Little regulation exists for illicit substances sold online. The main repercussion for selling poor product is mere internet shaming of a profile not connected to the dealer in any concrete way.[xiv] If this profile receives bad reviews and buyers know to steer clear, just set up another online profile selling the same product under a different username. Additionally, some suppliers, after using social media purely for its advertisement purposes, switch to encrypted messenger applications. This encryption hides from authorities information regarding when and where the actual handing off of payments and products will take place, and should authorities manage to find the information, it cannot be tracked back to a specific dealer.[xv] Anonymity increases supplier safety.

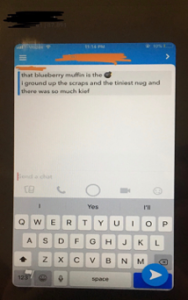

While an air of mystery around suppliers offers them safety, it can backfire for consumers who could be sold counterfeit product which may or may not be harmful. Again, the only form of regulation for illicit sales facilitated by social media is the experience of others, possibly comments on their posts or a few testimonials on their stories. Dealers do utilize this form of validation; on Snapchat for example, dealers may put screenshots of conversations they had with satisfied customers on their stories, as evidence that their product was well received. This validation means at least some reassurance regarding purchases from that dealer, but this is not a universal norm, and can faked with minimal effort. Consumers can never be entirely confident in what they are consuming.

Due to the accessibility of illicit substances as a result of social media, youth abuse drugs at a higher rate than ever. Nearly any drug can be purchased illicitly, and accessibility coupled with normality leads to increased experimentation and then dependency. Individuals under seventeen years of age are considered a vulnerable population when it comes to drug use and the development of dependency, and use at this age effects health for years to come. “The physical, mental health, and emotional harms from youth NUPM [non-medical use of prescription drugs] can have lasting impacts.”[xvi] Following long term use, marijuana can become addictive, and in 2012, a large portion of the US population over the age of twelve presented marijuana dependency. Smoking marijuana prior to adulthood leads to damaged neural connectivity and reduced prefrontal and hippo-campus activity, which manifests as a reduction in complex critical thinking skills and memory function. Marijuana is also widely considered a gateway drug as it reduces the effectiveness of the brain’s dopamine reward centers.[xvii] Despite the increasingly casual attitude surrounding it, marijuana does have the potential to be dangerous.

The changes in the ways illicit substances are marketed and purchased ripples into changes in the ways law enforcement must approach illicit markets for these substances. Dealer ability to switch to encrypted forms of communication prevents law enforcement from being able to find evidence with as much ease,[xviii] but when people do carry out transactions entirely online, new doors open for online evidence and increased assurance of conviction. “’Better to have a guy point a gun at you than the DEA have proof.’ Offline, a dealer … could get busted for any immediate transaction, but he would only be charged with that one crime; with digital evidence, he could wind up being prosecuted for deals conducted months or even years ago, despite those transactions not being directly observed.”[xix]

Changes originate from less conventional social media as well. Venmo, the online, monetary-transfer app, has teamed up to work directly with law enforcement in an effort to reduce its role in transferring money for illicit substances. Venmo is usually linked to a user’s bank account and is a public means of transferring funds in which the names of transfers are customizable, and users can view the transactions of any of their Venmo friends. Venmo catches drug dealers, such as Michael Getzler, by monitoring account activity and flagging transitions that seem questionable. In Getzler’s case, Venmo became suspicious when he told his customers to give the transactions funny names, which repeatedly ended up being clear references to marijuana. “We work collaboratively with law enforcement when appropriate to help ensure that Venmo is a safe place to send and receive money.”[xx]

Social media and developing internet based technologies impact both licit and illicit markets by changing the ways daily human interactions take place, introducing new methods for gathering information, and impacting thought and opinion. In the case of the black market for drugs like marijuana, this means a shift in safety for dealers and buyers, increased normalization and use, and the need for new ways of preventing illicit transactions.

[i] Snapchat, 2018, http://www.izisetup.com/Snapchat/?lp=a&geo=us&utm_medium=cpc&utm_source=yahoo&utm_

campaign=361748390&utm_content=9701110116&utm_term=305933040815&mt=e&bmt=e&adid=34292536698&s=&t=&d=&sl=5

[ii] Instagram, Googleplay, 2018 https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.instagram.android&hl=en_US

[iii] Dana P. Goldman, PhD and Anupam B. Jena, MD, PhD, “Growing internet use may help explain the rise in prescription drug abuse in the United States” US National Library of Medicine, May 12, 2011 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3884823/

[iv] History Cooperative, “The History of Social Media; Social Networking Evolution”, July 6, 2018 http://historycooperative.org/the-history-of-social-media/

[v] Dana P. Goldman, PhD and Anupam B. Jena, MD, PhD, “Growing internet use may help explain the rise in prescription drug abuse in the United States” US National Library of Medicine, May 12, 2011 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3884823/

[vi] History Cooperative, “The History of Social Media; Social Networking Evolution”, July 6, 2018 http://historycooperative.org/the-history-of-social-media/

[viii] Gary Vaynerchuck, “The Snap Generation; A Guide to the History of Snapchat” Huffington Post, January 2016, https://www.huffingtonpost.com/gary-vaynerchuk/the-snap-generation-a-gui_b_9103216.html

[ix] “Nationwide Trends” National Institute of Drug Abuse, June 2015, https://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/drugfacts/nationwide-trends

[x] Jessica Brown “The Powerful Way that Normalization Shapes Our World” BBC, March 20, 2017 http://www.bbc.com/future/story/20170314-how-do-we-determine-when-a-behaviour-is-normal

[xi] Adam Bear and Joshua Knobe, “The Normalization Trap” New York Times, January 28, 2017 https://www.nytimes.com/2017/01/28/opinion/sunday/the-normalization-trap.html

[xii] Adam Bear and Joshua Knobe, “The Normalization Trap” New York Times, January 28, 2017 https://www.nytimes.com/2017/01/28/opinion/sunday/the-normalization-trap.html

[xiii] Rachel Ferguson, “The Digital Underground: Here’s How You Can Buy Drugs on Social Media, Right Now” Complex, June 17, 2016 https://www.complex.com/life/2016/06/digital-underground-weed-market

[xiv] Victoria Ward and Jack Maidment, “Dealers Using Social Media Sites to Sell Drugs to Teenagers” The Telegraph, December 31, 2017 https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2017/12/31/dealers-using-social-media-sites-sell-drugs-teenagers/

[xv] Victoria Ward and Jack Maidment, “Dealers Using Social Media Sites to Sell Drugs to Teenagers” The Telegraph, December 31, 2017 https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2017/12/31/dealers-using-social-media-sites-sell-drugs-teenagers/

[xvi] Dana P. Goldman, PhD and Anupam B. Jena, MD, PhD, “Growing internet use may help explain the rise in prescription drug abuse in the United States” US National Library of Medicine, May 12, 2011 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3884823/

[xvii] Nora D. Volkow, MD., Ruben D. Baler, PhD., Wilson M. Compton, MD., and Susan R.R. Weiss, PhD “Adverse Health Effects of Marijuana Use” The New England Journal of Medicine, June 5, 2015 https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/nejmra1402309

[xviii] Victoria Ward and Jack Maidment, “Dealers Using Social Media Sites to Sell Drugs to Teenagers” The Telegraph, December 31, 2017 https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2017/12/31/dealers-using-social-media-sites-sell-drugs-teenagers/

[xix] Rachel Ferguson, “The Digital Underground: Here’s How You Can Buy Drugs on Social Media, Right Now” Complex, June 17, 2016 https://www.complex.com/life/2016/06/digital-underground-weed-market

[xx] Conor Skelding, “Students Fret Over Venmo Payments to Alleged Drug Dealer” Politico New York, April 3, 2015 https://www.politico.com/states/new-york/city-hall/story/2015/04/students-fret-over-venmo-payments-to-alleged-drug-dealer-021055

Bibliography

Adam Bear and Joshua Knobe, “The Normalization Trap” New York Times, January 28,

2017 https://www.nytimes.com/2017/01/28/opinion/sunday/the-normalization-trap.html

Conor Skelding, “Students Fret Over Venmo Payments to Alleged Drug Dealer” Politico New

York, April 3, 2015 https://www.politico.com/states/new-york/city-hall/story/2015/04/students-fret-over-venmo-payments-to-alleged-drug-dealer-021055

Dana P. Goldman, PhD and Anupam B. Jena, MD, PhD, “Growing internet use may help explain the rise in prescription drug abuse in the United States” US National Library of Medicine, May 12, 2011 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3884823/Gary Vaynerchuck, “The Snap Generation; A Guide to the History of Snapchat” Huffington

Post, January 2016, https://www.huffingtonpost.com/gary-vaynerchuk/the-snap-

generation-a-gui_b_9103216.html

History Cooperative, “The History of Social Media; Social Networking Evolution”, July 6, 2018

The Complete History of Social Media: A Timeline of the Invention of Online Networking

Instagram, Googleplay, 2018 https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.instagram.

android&hl=en_US

Jessica Brown “The Powerful Way that Normalization Shapes Our World” BBC, March 20,

2017 http://www.bbc.com/future/story/20170314-how-do-we-determine-when-a-behaviour-is-normal

Joseph Banken, “Drug Abuse Trends Among Youth in the United States” US National Library of

Medicine, October 2004 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15542750

“Nationwide Trends” National Institute of Drug Abuse, June 2015,

https://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/drugfacts/nationwide-trends

Nora D. Volkow, MD., Ruben D. Baler, PhD., Wilson M. Compton, MD., and Susan R.R.

Weiss, PhD “Adverse Health Effects of Marijuana Use” The New England Journal of Medicine, June 5, 2015 https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/nejmra1402309

Rachel Ferguson, “The Digital Underground: Here’s How You Can Buy Drugs on Social Media,

Right Now” Complex, June 17, 2016 https://www.complex.com/life/2016/06/digital-underground-weed-market

Snapchat, 2018, http://www.izisetup.com/Snapchat/?lp=a&geo=us&utm_medium=

cpc&utm_source=yahoo&utmcampaign=361748390&utm_content=9701110116&utm_term=305933040815&mt=e&bmt=e&adid=34292536698&s=&t=&d=&sl=5

Victoria Ward and Jack Maidment, “Dealers Using Social Media Sites to Sell Drugs to

Teenagers” The Telegraph, December 31, 2017 https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/

2017/12/31/dealers-using-social-media-sites-sell-drugs-teenagers/

Ylan Mui and Karen James Sloan, “How Bitcoin is Fueling America’s Opioid Crisis” CNBC

April 13, 2018 https://www.cnbc.com/2018/04/13/how-bitcoin-and-cryptocurrencies-are-fueling-americas-opioid-crisis.html