15 Bloomington’s Opioid Crisis

-by Anoop Sai Chinthala

“They just want to stop hurting,” says Jennifer Tafoya talking about her recently deceased stepdaughter.[i] A resident of Monroe County, Dominque was 19 when she overdosed on heroin. Admitting to trying all sorts of drugs, Dominique found relief through heroin. Unfortunately, she is not the only one to die from opioid addiction at a young age. On average, more than 115 people overdose on opioids in the United States every day.[ii] The National Institute of Drug Abuse recognizes the abuse of opioids–including prescription pain relievers–as a national crisis as it damages numerous cities’ public health and economic welfare. Damages are estimated to cost the United States $78.5 billion annually, and a majority of that damage comes from the Midwest.[iii] Indiana itself spent $4.3 billion in 2017 on solely economic damages–medical expenses, costs of repair, loss of property use and value–caused by opioid misuse.[iv] Some counties in Indiana recorded high amounts of addiction in their area by observing the rate of newly-identified HIV cases. These counties include Scott county, Marion county, Allen county, and Monroe county, the home of Indiana University.[v] In Bloomington the combination of poverty and impulsive characteristics of college students fosters an environment susceptible to opioid black-market activity, making it a profitable area with high demand.

Although prescribed legally, people often sell their opioid prescriptions to the highest bidder or give whatever is remaining to their friends–especially college students.[vii] Young adults, aged between 18 and 25, are at highest risk of opioid abuse.[vi] As a result, one in four universities had an annual prescription opioid use prevalence of 10% or higher.[viii] Opioid abuse increases among white college students as well as residents of fraternities and sororities.[ix] The prominence of Greek life at Indiana University cultivates a party culture that leads students to be more susceptible to drugs such as opioids.[x] Students in Greek life are more willing to try various drugs and are also very susceptible to peer pressure,[xi] making them a desired target population for drug dealers. Currently at IU, 70 fraternities and sororities consist of over 8,200 students.[xii] Having a large population involved, either buying or selling, in the illicit drug markets at IU creates a high demand that suppliers use to their advantage. The increase in demand results in an increase in suppliers which creates a viscous cycle that brings drugs into the market.

Other pre-existing drug markets also lead to Bloomington’s opioid market. Black markets tend to attract more black markets, especially drug markets. From personal experience, a majority of college students commonly use marijuana more often than high school students. At IU, people normalize using drugs or abusing prescriptions, such as Adderall. During my freshman year, my first exposure to common drug use shocked me. Some of my close high school friends lived on campus and shared stories of their peers smoking every night. Eventually, some of these people transitioned to abusing prescription drugs, such as Xanax. The situation escalated to the point where IUPD officers arrested one of their floor mates for selling these types of drugs. By the time freshman year ended, friends who I viewed as pure and innocent now smoke pot regularly and friends who used to smoke now do stronger drugs.

Dealers also go through a similar process. They start dealing “easy” drugs such as marijuana but eventually move to stronger drugs such as opioids because they can make more money. The higher the risk the higher the reward. College students are at higher risk for substance abuse given their age because going to a big school like IU will expose students to various cultures as well as habits, either good or bad, of other people. Since college students are high risk for opioid abuse, it also means that they are at high risk of opioid black-market involvement.[xiii]

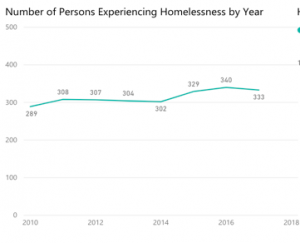

IU students, however, are not the only people that contribute to the opioid epidemic in Bloomington. Poverty plays a key role in illicit markets. Black markets often draw in people in poverty, such as homeless individuals, including those dealing with addiction and substance abuse. In Bloomington, a little over 300 persons experience homelessness by year.[xiv] Homelessness can result from substance abuse or cause substance abuse. According to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 26% of all homeless people struggle with some form of drug abuse.[xv] People typically think that drug abuse causes homelessness as drug abusers struggle to keep jobs and maintain healthy relationships with friends and families, which often results in the loss of a place to live. But in a majority of situations, it is vice versa. Homeless people turn to drug abuse to cope with their situation.[xvi] Therefore, homelessness causes an increase in drug abuse.[xvii]

Compounding problems of homelessness in Bloomington, high opioid prescription rates feed the opioid epidemic in Monroe county. With a rate of 63.9 opioid prescriptions per 100 people, people have minimal difficulty obtaining opioids, including those vulnerable to substance abuse.[xviii] The number of persons experiencing homelessness per year in a specific area provides insight to the drug problem.

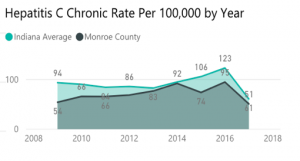

As many individuals who become homeless turn to drug abuse, and as opioids are common, a rise in the number of homeless people would increase the amount of opioid abuse, which is consistent with figures 1 and 2.

Looking at Figure 2, the number of persons experiencing homelessness in Monroe county per year began to rise from 2014 to 2016.[xxi] The Hepatitis C chronic rates also began to rise during this time (see Figure 1). The main reason Hepatitis C indicates opioid abuse is due to those sharing needles, increasing the risk of contracting Hepatitis C. Therefore, a rise in Hepatitis C rates occurred during the same time as a rise in the number of homeless is most likely a result of increases in opioid use.

Following the rise in the infection rate, Monroe County officials declared a public emergency.[xxii] Nonprofits and various addiction programs started as a result of opioid abuse and overdoses in Bloomington. The Shalom Center is an inclusive resource center in Bloomington that started in 2000 to help the homeless and those in poverty. Since 2008, the center has provided more than seventy thousand meals a year.[xxiii] Bloomington set up various needle exchange programs to combat the spread of disease through needle sharing. Since the implementation of this program, the number of homeless and the rate of Hepatitis C decreased.[xxiv] Locally, Indiana University offers alcohol and drug resources through counseling and the campus alcohol and drug information center. All these programs started in order to battle drug abuse, specifically opioid abuse, whether directly by helping the addict or indirectly by reducing the spread of disease and the number of people in poverty.

The opioid black market thrives in Bloomington. The market affects various legislation and pressures large surrounding facilities, such as Indiana University, to get involved. Recently, the university committed to investing $50 million to collaborate with various communities to prevent and reduce opioid abuse as well as addiction.[xxv] Most of the changes focus on expanding treatment to pregnant women and mothers as well as making treatment more accessible. These changes emphasize treatment to pregnant women because of the above average amounts of babies that are born addicted to opioids in Indiana.[xxvi] Other parts of Indiana University’s investment will go to forming mobile treatment teams, developing a plan to increase residential drug treatment in the state, easing requirements for creating needle exchange programs, and restricting opioid prescriptions. By restricting prescriptions, Indiana’s government is targeting one source of opioid distribution.

The presence of the opioid black market in Bloomington can be difficult to pinpoint. By looking at various factors such as the demographic of the area, the living conditions, and the legislation on a local and even state-wide scale, the effects of the opioid market become apparent. First, the spread of Hepatitis C and HIV are key indicators of the presence of opioids due to the sharing of needles. Secondly, black markets attract more black markets. The combination of Greek life and the curiosity of college students/young adults creates a profitable environment with high demand. The high demand brings in more black markets that not only impact the campus but also the city. Lastly, poverty is crucial to the expansion of the opioid black market because people in desperate situations are an easy group to sell to as well as get involved in the black market.

[i] Lane, Laura. “This Is Opioid Addiction: A Herald-Times Special Report.” The Hoosier Times, 22 Sept. 2018. Accessed December 4, 2018. www.hoosiertimes.com/herald_times_online/news/this-is-opioid-addiction-a-herald-times-special-report/article_50aae24c-fa5b-5ac2-a176-09481e35aec8.html.

[ii] “Opioid Overdose Crisis.” National Institute on Drug Abuse. March 2018. Accessed October 15, 2018. https://www.drugabuse.gov/drugs-abuse/opioids/opioid-overdose-crisis

[iii] ibid

[iv] Brewer, Ryan M., Freeman, Kayla M. “Cumulative Economic Damages from 15 years of Opioid Misuse Throughout Indiana.” Indiana Business Review. Spring 2018. Accessed October 14, 2018. http://www.ibrc.indiana.edu/ibr/2018/spring/article1.html

[v] “Indiana State Department of Health: County Opioid Profile.” Mayor’s Office of Innovation. Accessed October 15, 2018. https://www.bloomingtonrevealed.com/community-health/

[vi] James, Susan D. “Opioid Crisis: How America’s Colleges are Reacting to the Epidemic.” NBC News. August 31, 2017. Accessed October 15, 2018. https://www.nbcnews.com/feature/college-game-plan/opioid-crisis-how-america-s-colleges-are-reacting-epidemic-n797696

[vii] “Opioid Abuse in College Students Requires Increased Efforts.” Psychiatric Annals. October 30, 2017. Accessed October 15, 2018. https://www.healio.com/psychiatry/addiction/news/online/%7Bda3b60b9-cc6c-4bd6-b9ea-70b48f79f42a%7D/opioid-abuse-in-college-students-requires-increased-efforts

[viii] ibid

[ix] ibid

[x] “Drinking and Drug Abuse in Greek Life.” AddictionCenter, Accessed September 27, 2018. www.addictioncenter.com/college/drinking-drug-abuse-greek-life/.

[xi] ibid

[xii] “Fraternity and Sorority Life.” Division of Student Affairs. Accessed October 15, 2018. https://studentaffairs.indiana.edu/student-life-learning/fraternity-sorority/index.shtml

[xiii] Arria, Amelia M et al. “Drug exposure opportunities and use patterns among college students: results of a longitudinal prospective cohort study” Substance abuse vol. 29,4 (2008): 19-38.

[xiv] “Safe, Civility, and Justice Data Sets.” Mayor’s Office of Innovation. Accessed October 15, 2018. https://www.bloomingtonrevealed.com/safe-civil-just-city

[xv] “Substance Abuse and Homelessness.” National Coalition for the Homeless. July 2009. Accessed October 15, 2018. https://www.nationalhomeless.org/factsheets/addiction.pdf

[xvi] ibid

[xvii] ibid

[xviii] “Opioid Overdose.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 31 July 2017, Accessed December 5, 2018. www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/maps/rxcounty2017.html.

[xix] “Safe, Civility, and Justice Data Sets.”

[xx] ibid

[xxi] ibid

[xxii] ibid

[xxiii] ibid

[xxiv] ibid

[xxv] Carden, Dan. “Indiana University to Spend $50M Researching Drug Addiction in State.” Nwitimes. October 10, 2017. Accessed October 14, 2018. https://www.nwitimes.com/news/local/govt-and-politics/indiana-university-to-spend-m-researching-drug-addiction-in-state/article_7fb0acaf-9b38-5209-9198-69acc60bf6e7.html#2

[xxvi] ibid

Bibliography

Arria, Amelia M et al. “Drug exposure opportunities and use patterns among college students: results of a longitudinal prospective cohort study” Substance abuse vol. 29,4 (2008): 19-38.

30, 2017 October. “Opioid Abuse in College Students Requires Increased Efforts.” Healio, SLACK Incorporated, www.healio.com/psychiatry/addiction/news/online/%7Bda3b60b9-cc6c-4bd6-b9ea-70b48f79f42a%7D/opioid-abuse-in-college-students-requires-increased-efforts.

Substance Abuse and Homelessness . National Coalition for the Homeless, July 2009, www.nationalhomeless.org/factsheets/addiction.pdf.

“A Safe, Civil, and Just City.” Bloomington,IN Mayor John Hamilton, www.bloomingtonrevealed.com/safe-civil-just-city.

“Community Health.” Bloomington,IN Mayor John Hamilton, www.bloomingtonrevealed.com/community-health/.

Carden, Dan. “Indiana University to Spend $50M Researching Drug Addiction in State.” Nwitimes. October 10, 2017. Accessed October 14, 2018. https://www.nwitimes.com/news/local/govt-and-politics/indiana-university-to-spend-m-researching-drug-addiction-in-state/article_7fb0acaf-9b38-5209-9198-69acc60bf6e7.html#2

Cumulative economic damages from 15 years of opioid misuse throughout Indiana Ryan M. Brewer, Ph.D., MBA Associate Professor of Finance, Indiana University Division of Business, Indiana University–Purdue University Columbus Kayla M. . “Cumulative Economic Damages from 15 Years of Opioid Misuse throughout Indiana.” The Importance of Education for the Unemployed, www.ibrc.indiana.edu/ibr/2018/spring/article1.html.

“Drinking and Drug Abuse in Greek Life.” AddictionCenter, www.addictioncenter.com/college/drinking-drug-abuse-greek-life/.

“Indiana University Bloomington.” Attendance Concerns: Dean of Students: Division of Student Affairs: Indiana University Bloomington, studentaffairs.indiana.edu/student-life-learning/fraternity-sorority/index.shtml.

James, Susan Donaldson. “Opioid Crisis: How America’s Colleges Are Reacting to the Epidemic.” NBCNews.com, NBCUniversal News Group, 31 Aug. 2017, www.nbcnews.com/feature/college-game-plan/opioid-crisis-how-america-s-colleges-are-reacting-epidemic-n797696.

Lane, Laura. “This Is Opioid Addiction: A Herald-Times Special Report.” The Hoosier Times, 22 Sept. 2018, www.hoosiertimes.com/herald_times_online/news/this-is-opioid-addiction-a-herald-times-special-report/article_50aae24c-fa5b-5ac2-a176-09481e35aec8.html.

National Institute on Drug Abuse. “Opioid Overdose Crisis.” NIDA, 6 Mar. 2018, www.drugabuse.gov/drugs-abuse/opioids/opioid-overdose-crisis.

“Opioid Overdose.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 31 July 2017, www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/maps/rxcounty2017.html.