17 Fashion In The Lens Of Its True Cost

-by Sharon Hsu, L216 Project

As the weekend comes along, you realize you have an event to attend in a few hours. You dig through the closet and try on multiple outfits but nothing feels right. In the spur of the moment, you head over to the mall and begin shopping for a last-minute outfit. An hour later, you walk out of your local H&M store with a $4.99 T-shirt and a pair of $9.99 jeans.[1] Ten years ago, the spontaneous purchasing of a new wardrobe would have been impossible. Our fashion habits have changed significantly due to the rise of companies like H&M, Zara and Forever 21. A new era for the fashion industry called fast fashion has emerged. Fast-fashion brands compete by pushing new styles and sales weekly, allowing consumers to buy stylish clothing at a low price and a rapid pace. This transformation seems beneficial but the true costs behind fast fashion far exceed our imaginations. The purchases we make here in the US affects factory workers and their families in Bangladesh and India, the farmers in Texas, the designers in Europe, the environment in Africa, and we as US consumers. Fast fashion takes a heavy toll on the livelihoods of people around the world.

As part of the global chain, our actions appear small and insignificant. However, if we track the traces of our purchases, we discover the magnitude of our impact. The $4.99 T-shirt attracts consumers and incentivizes them to buy more products more frequently. For fast-fashion companies, their profits have continue to skyrocket.[2] In fact, the founder of Zara briefly took the title of “World’s richest man” in 2017.[3] The low price point seemingly benefits consumers and businesses, but in reality, the price cannot sustain everyone in the supply chain. In order to profit, fast-fashion companies have to lower production costs and minimize money spent on factories and materials. Factories, in order to compete, are “forced to”[4] operate with limited budget. Due to the rise of wages and stricter labor rules, companies outsource production to developing countries. Globalization helped businesses but “created the opportunity for companies to take advantage of the system”.[5] Since factories operate on a low budget, management are forced to lower the wages of their factory workers, cut corners with the factories’ conditions and obtain lower quality materials. In the US, companies cannot get away with poor working conditions but in a small town in India, laws are not strictly enforced. Companies can “get away with just about anything”.[6]

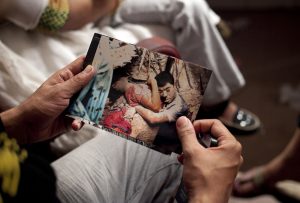

Your $4.99 purchase at H&M affects how much factory workers get paid. Most people working in these factories are stuck in a cycle. They work at these factories hoping to provide for family, yet the low pay is not enough to cover expenses, let alone to save up. Parents cannot afford education for their children, forcing the next generation to continue to obtain a job in a factory at a young age. Shima Akhter is among the 3.5 million garment workers in Bangladesh who is affected by our purchases.[7] Akhter moved to Dhaka, Bangladesh when she was 12 and soon began her job in a garment factory to help support her family. According to “The War on Want”, garment workers in Bangladesh earn about $29 a month. Although the living cost in Bangladesh is low, it still takes around $53 to provide for a family.[8] Aside from low pay, workers like Shima Akhter also endure long hours, around 14-16 hours of work a day. Since 85% of the garment workers are women, this schedule forces mothers to separate from their children.[9] Due to the circumstances, Akhter made the hard decision of sending her daughter to relatives in another town. Throughout the years, Akhter fought for better pay at her factory by assembling a union but as soon as management found out, Akhter was gruesomely beaten.[10] Factories discourage union activities to keep the workers under tight control.[11] However, without unions pushing for better working conditions, companies will always put profits first.

Fast fashion profits through mass production. Every other week, companies like H&M release new styles. This not only puts factories on a tight schedule but also requires new factories be built daily to meet the demands. Unfortunately, rushing to build new factories leads to poor structures.[12] The problems of unsafe factories were neglected until 2013. On the morning of April 24, 2013 in Dhaka, Bangladesh, the garment workers working in Rana Plaza went to work like any other day. The only difference was, workers noticed the deep cracks on the walls of the building. The worried workers reported the cracks and begged management to fix the problem before sending them into work. If management reconstructed the building, production would be severely delayed so instead, they forced the workers in. Some time before 9 am, the ceilings collapsed, the floors vanished and workers fell from this five-story-tall building.[13] The building took less than 90 seconds to collapse, which took the lives of 1,134 people.[14]

Rana Plaza alarmed many people as it revealed the inhumane conditions of these factories. Not many workers survived the incident but those who lived, carried expensive medical bills, had amputated body parts or severe damage. These survivors continue to suffer both physically and mentally. The fast-fashion companies responsible were far away from the incident so the impact on them was minimal.

However, Rana Plaza had the world noticing these poor working conditions. The years before Rana Plaza, about 71 workers died each year in building fires or collapses. In the year since, it is about 17 people annually.[15] People began to take action on holding fast-fashion brands accountable. For example. two major brands agreed to pay million of dollars in December, 2014, and January, 2015, after failing to compel suppliers to fix their factories.[16] This is a small victory for factory workers but there are more hidden dangers.

Garment factories often contain chemicals. These chemicals are used to dye fabrics and polish leathers.[17] In order to keep up the pace for fast fashion, factories do not handle heavy chemicals properly. Kanpur, India is one of the major places that exports leather.[18] The factories here offer cheap, mass production for leather. However, without taking the proper time and care to handle chemicals, toxins affect the health of factory workers and the people around town. Chromium, one of the heavy chemicals required to treat the leather, gets released into the water. These toxins pollute the farming water, drinking water and one of the important holy rivers-Ganga. Fast fashion not only impacts the lives of their factory workers but also the innocent people living near the factories. People of Kanpur face dermal problems, from skin rashes to numbness in the limbs.[19] Ironically, derma problems are considered a small issue. A huge population of people in Kanpur suffer from Jaundice. Though this condition is treatable, most families have to spend their low wages on large medical bills.

Beyond the factory, fast fashion also contaminates the soil. Cotton produces the fiber essential to what we wear. In order to produce cotton, “the land is almost reconsidered as a factory.” Companies turn to chemicals like pesticides to increase production. Monsanto is one of the leading companies that creates “agricultural advancements” through products like pesticide. Monsanto sells farmers modified seeds that supposedly require less pesticide and yield higher results. This results in a “seed monopoly.” Farmers purchase the modified seeds in the beginning hoping to use less pesticides. When the results are not shown, farmers turn to stronger pesticides. Monsanto, also owning monopoly in pesticides continue to profit from the poor farmers. Year after year, insects increase their resistance to the pesticides and the land degrades from chemical use. Worst of all, farmers and their families see negative effects to their health from these chemicals. Around the cotton farms in India, doctors have discovered problems like cancer, severe mental retardation, physical disabilities. Many health problems are birth defects. “Most of the people just accepts their children’s death, they can only wait for the children’s death,” doctors explained.[20] Innocent people suffer from the consequences and are paid too little to have adequate health care.

Problems in India seem far away, but health concerns are also happening in the United States. Texas planted approximately 13.1 million acres of cotton in 2018.[21] A Texas cotton farmer lost her husband in 2005. Her late husband suffered from “glioblastoma multiforme,” a brain tumor that is commonly found in men working in agricultural fields. She described how easy it was to find a doctor to operate on the brain tumor, as they “do so many of them.” Though she could not prove directly that the chemicals used in cotton farming led to her husband’s death, “there was just too many linkages.”[22] In fact, Monsanto recently lost a lawsuit to a US school groundskeeper who argued that Monsanto’s products led to his cancer.[23] Again and again, chemicals negatively affect human health. These chemicals used on the cottons transfer to the clothes we buy, then eventually transfer onto our skin.[24] If people remain careless about the quality of their clothing, fast-fashion companies will never take the impact on our health seriously.

Aside from health problems, intellectual property is another issue that hits home. Intellectual property may seem like a trivial problem compared with life and death, but it is very essential. Fashion designers over Europe have been affected by fast-fashion companies. Stolen intellectual property causes sales to drop and companies to go bankrupt. In return, the jobs of these designers, manufactures and many more are affected. Fast fashion and the illicit market it creates begins to compete with the licit market. The more we purchase through fast-fashion companies, the weaker the licit market becomes, and slowly, more people will join the illicit market out of desperation. Designers put in a lot of effort creating original designs, all from picking the finest fabric to hand stitching every detail. Fast-fashion brands, however, take these designs and send it to factories for mass production. Seema Anand, the CEO of Simonia Fashions, is one of many companies that make inexpensive clothes inspired by other designers’ runway looks. The companies clients are trendy stores like Forever 21. “If I see something on Style.com, all I have to do is e-mail the picture to my factory and say, ‘I want something similar, or a silhouette made just like this,’ ” Anand said in an interview with the New York Times back in 2007. Anand mentioned how factories, in Jaipur, India, can deliver stores a knockoff months before the designer version. When these products debut months before the designer ones come out, it is hard to identify the counterfeit, yet the price difference is astounding. Anand created a dress that is nearly identical with Tory Burch, a famous luxury brand. The Tory Burch dress sells for $750 and Anand’s dress sells for $260 at Bloomingdale’s.[25] For us consumers, money is saved. For authentic designers, all their efforts are in vain.

Since fast-fashion companies made clothes affordable, people purchase more frequently. Before, people used to shop every few months; when they have outgrown their clothes or purchase new styles. Now, the average person shops for clothing every other week.[26] New email alerts for upcoming sales pop up daily. Celebrities and influencers constantly post on their social media about their outfits. Advertisements about customers feeling happier after their new purchase work like propaganda. People no longer purchased out of need but out of greed. Consumerism creates desire; people never have enough clothes to wear or always need that extra pair of shoes. Psychologists found links between materialism and mental health issues. The amount of joy one gets from shopping correlates with the likelihood to suffer from depression.[27] As our closets grow, textile wastes also soar. Clothes that no longer fit in our closet get donated to charity. Yet, people know little of what happens after the clothes are sent to these organizations. Many of these unwanted clothing are “dumped” into third world countries.[28]

When you purchase the $4.99 T-shirt, you don’t have to think twice. It is cheap and stylish. The next time you have another event, you purchase another shirt. Time after time, our consumption of cheap clothing pushes fast- fashion companies to increase their production. In order to keep lowering the price and maximizing the profit, the conditions only worsen. The workers will continue to be paid an unreasonable wage and forced to work in a dangerous environment. The farmers and their families will continue to suffer from sickness. The environment will continue to be polluted. The consumers, people like you and I, continue to take part in this black market. Only the companies, the fast-fashion brands will continue to thrive. Our purchases from these fast-fashion brands satisfy our needs briefly, yet they only create careless production and endless consumption.

-

H&M Website

-

https://www.forbes.com/companies/hm/#4e8e473f7280

-

https://www.cnbc.com/2017/08/30/zara-founder-amancio-ortega-is-now-the-richest-person-in-the-world.html

-

“The True Cost.” Netflix. N.p., 17 July 2015. Web. 14 Oct. 2018.

-

See 4.

-

The True Cost.” Netflix. N.p., 17 July 2015. Web. 14 Oct. 2018.

-

See 6.

-

“Sweatshops in Bangladesh.” War on Want. N.p., 23 June 2015. Web. 15 Oct. 2018.

-

See 11.

-

Chamberlain, Gethin. “India’s Clothing Workers: ‘They Slap Us and Call Us Dogs and Donkeys’.” The Guardian. Guardian News and Media, 25 Nov. 2012. Web. 14 Oct. 2018.

-

“The True Cost.” Netflix. N.p., 17 July 2015. Web. 14 Oct. 2018.

-

See 6.

-

See 5.

-

Rushe, Dominic, and Michael Safi. “Rana Plaza, Five Years On: Safety of Workers Hangs in Balance in Bangladesh | Michael Safi and Dominic Rushe.” The Guardian. Guardian News and Media, 24 Apr. 2018. Web. 15 Oct. 2018.

-

See 9.

-

See 5.

-

“The True Cost.” Netflix. N.p., 17 July 2015. Web. 14 Oct. 2018.

-

See 15.

-

See 15.

-

See 15.

-

“NCC Survey: 13.1 Million Acres of Cotton in 2018.” Texas Farm Bureau. N.p., 12 Feb. 2018. Web. 14 Oct. 2018.

-

See 15.

-

“The Latest: Judge Weighs Jury $289 Million Monsanto Verdict.” The Washington Post. WP Company, 10 Oct. 2018. Web. 14 Oct. 2018.

-

“Toxins Remain in Your Clothes.” ScienceDaily. ScienceDaily, 23 Oct. 2015. Web. 14 Oct. 2018.

-

Wilson, Eric. “Fashion Industry Grapples with Designer Knockoffs.” The New York Times. September 04, 2007. Accessed September 07, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2007/09/04/business/worldbusiness/04iht-fashion.1.7373169.html.

-

“The True Cost.” Netflix. N.p., 17 July 2015. Web. 14 Oct. 2018.

-

See 24.

28. See 24.

Bibliography

Chamberlain, Gethin. “India’s Clothing Workers: ‘They Slap Us and Call Us Dogs and Donkeys’.” The Guardian. Guardian News and Media, 25 Nov. 2012. Web. 14 Oct. 2018.

H&M Website

https://www.forbes.com/companies/hm/#4e8e473f7280

https://www.cnbc.com/2017/08/30/zara-founder-amancio-ortega-is-now-the-richest-person-in-the-world.html

“NCC Survey: 13.1 Million Acres of Cotton in 2018.” Texas Farm Bureau. N.p., 12 Feb. 2018. Web. 14 Oct. 2018.

Rushe, Dominic, and Michael Safi. “Rana Plaza, Five Years On: Safety of Workers Hangs in Balance in Bangladesh | Michael Safi and Dominic Rushe.” The Guardian. Guardian News and Media, 24 Apr. 2018. Web. 15 Oct. 2018.

“Sweatshops in Bangladesh.” War on Want. N.p., 23 June 2015. Web. 15 Oct. 2018.

“The Latest: Judge Weighs Jury $289 Million Monsanto Verdict.” The Washington Post. WP Company, 10 Oct. 2018. Web. 14 Oct. 2018.

“Toxins Remain in Your Clothes.” ScienceDaily. ScienceDaily, 23 Oct. 2015. Web. 14 Oct. 2018.

Wilson, Eric. “Fashion Industry Grapples with Designer Knockoffs.” The New York Times. September 04, 2007. Accessed September 07, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2007/09/04/business/worldbusiness/04iht-fashion.1.7373169.html.