13 Kurosawa’s Stray Dog & Japan’s Apres Guerre

-by Chase Hastings

-by Chase Hastings

Akira Kurosawa’s 1949 film Stray Dog shows a vivid picture of the seedy underworld during post World War II Japan. It centers on the rookie detective Murakami and follows his mission to find his stolen colt pistol. Along the way he encounters the harsh realities of post-war Japan, and the black market that has claimed his gun. Moreover, Murakami must grapple with the fact that someone already used his gun in a mugging after one day. Murakami is on a race against time to find his gun before more people are harmed. In this quest, Murakami joins veteran detective Sato to apprehend the violent mugger and trace the shady trail of his pistol. However, the most challenging obstacle Murakami confronts is his growing empathy towards the person he must apprehend, Yusa, and the shady morality of apres guerre (postwar) Japan. [i] Plot wise, Stray Dog is categorized in the detective genre of films, but it actually feels more like a character study than a thriller. With each character, Kurosawa lends a detailed peek into not only what the black market looked like, but also Japan’s perplexed state of mind right after the war. Japan’s government and its people stood “at a crossroads” between licit and illicit, necessity and opportunity, good and evil. [ii] Fundamentally Kurosawa uses detective Murakami to represent Japan’s post-war identity crisis and detective Sato to propose an ideal Japanese social order and ultimately comment on the tragedy of the apres guerre.

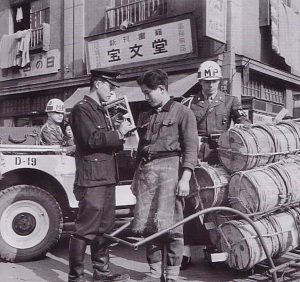

Murakami identifies with the perpetrator, Yusa, and the people of the underworld more and more to express Japan’s reluctant identification with the black markets. Near the beginning of the movie, when Murakami goes undercover and wanders the streets to find an illicit arms dealer, he dresses as a homeless veteran to blend in to the crowds, but also to attract a pistol dealer’s attention. [iii] Like real life, the public saw veterans in post-war Japan as the “country’s new outcasts” and shunned for losing the war, and committing “unspeakable acts” throughout Asia in the Philippines, China, Guam. [iv] Social outcasts like veterans and even war orphans or widows were forced to turn to the outskirts of society “to scramble for daily survival on the streets” like stray dogs. Murakami strays along the streets in a nine minute montage of overlapping footage of crowded streets, packs of dirty children, clouds of cigarette smoke, people shoveling down rice bought from an illegal food stand, prostitutes standing against shadowed walls, guys dressed in ragged Hawaiian aloha shirts, closeups of Murakami’s shuffling feet and shifting eyes, loud jazz music playing in the night, cops chasing after people, the sun shining through a tattered awning, displaced people lying on the streets, groups of crouched men huddled together talking privately, and rain falling over shelters to “evoke a world in perpetual motion” and the “jungle like nature” of the black market. [v] [vi] Despite the passage of time, from night to day, outside to indoors, clear to rainy, and the endless movement, the world of the black market, its people, and Murakami stay the same. For the people of the black market, there is “no clear future” and “all seemed irrelevant to the dark faces gathered in the black market.” [vii] Moreover, the shots that are stacked on top of eachother emphasize that the world, like Murakami in his so far unsuccessful mission, is stuck. Also, ironically, like Yusa, Murakami is an ex-soldier, roaming the streets “experiencing a life he might have led” if he hadn’t become a police detective. [viii]

Murakami is symbolic of Japan at the time. In trying to contend with the problem of the black markets Japan is like Murakami, chasing its “own shadow” by tracking the markets, trying to control them on one hand but also realizing that “for many Japanese, the markets were virtually the economy.” [ix] Getting rid of the markets would be detrimental for the everyday person who relied on them for survival and a basic living. Due to the massive inflation caused by the war “the government ordered all banks to limit monthly cash withdrawals from savings accounts to 300 yen per family head plus 100 yen for each dependent” and prescribed a maximum on monthly consumer spending of 500 yen. [x] Due to the high cost of living, however, most people needed to spend more. Reportedly the average cost of living rose 850 percent “between the surrender in August, 1945 and May, 1946.” What’s worse is that in April 1946 the monthly cash withdrawal decreased again from 300 to 100 yen, making it more impossible to afford adequate civilian goods. Also the government minimized the amount of civilian goods produced largely because more than half of the country’s manufacturing facilities had been destroyed by the war” including over 400 war plants seized by the Allied Forces for reparations. [xi]

Murakami is symbolic of Japan at the time. In trying to contend with the problem of the black markets Japan is like Murakami, chasing its “own shadow” by tracking the markets, trying to control them on one hand but also realizing that “for many Japanese, the markets were virtually the economy.” [ix] Getting rid of the markets would be detrimental for the everyday person who relied on them for survival and a basic living. Due to the massive inflation caused by the war “the government ordered all banks to limit monthly cash withdrawals from savings accounts to 300 yen per family head plus 100 yen for each dependent” and prescribed a maximum on monthly consumer spending of 500 yen. [x] Due to the high cost of living, however, most people needed to spend more. Reportedly the average cost of living rose 850 percent “between the surrender in August, 1945 and May, 1946.” What’s worse is that in April 1946 the monthly cash withdrawal decreased again from 300 to 100 yen, making it more impossible to afford adequate civilian goods. Also the government minimized the amount of civilian goods produced largely because more than half of the country’s manufacturing facilities had been destroyed by the war” including over 400 war plants seized by the Allied Forces for reparations. [xi]

Occasions where the government and police actively work with black marketers and yakuza (Japanese mafia) show the moral grayness Japan felt toward black markets and the underworld. At the time and still today, the yakuza tend to control most of the black markets. [xii] On one occasion, called the Kobe incident, a gang of Chinese, Taiwanese, and Korean gangsters kidnapped a group of police officers. The police force didn’t have the manpower to get the hostages back, so the mayor of Kobe enlisted the help of the Yamaguchi-gumi yakuza group to resolve the incident. [xiii] At the time the police were seen as “venal if not thoroughly corrupt” and incompetent in helping people. In another incident a man’s overcoat was stolen, so naturally he went looking for it on the black market and found it. He then called two police detectives only for them to tell him he needed to “negotiate the matter with the market bosses.” He ended up having to buy the coat back for 500 yen, roughly 71% of his paycheck he earned in a month. [xiv] The government had no choice but to look at the black markets with reluctant approval.

Additionally, Murakami’s recollective, regretful outlook is reminiscent of how Japan as a society felt ashamed of its part in the war and stigmatized veterans. When Murakami is first put on the case, he admits with remorse to Sato that the mugger used his colt to shoot the woman. He continues to regretfully say how he “screwed up” and even though Sato replies that if it wasn’t a colt it would’ve been someone else’s gun, Murakami is still distressed about everything falling apart because he lost his gun. [xv] Murakami’s negative way of thinking about the past is indicative of how many Japanese outcasts felt in the post war. When soldiers returned home from the war, the public met them with hostility for committing atrocities in the war, even though many “expressed regret for their crimes” and pleaded to the public for forgiveness. [xvi] According to one veteran writing from a sanitarium to the editor section of the Japanese newspaper Asahi, “the existence of us injured and ill veterans is forgotten . . . I myself am five minutes away from hanging.” [xvii] Not only regretful memories tormented and haunted veterans, to the public they physically represented the regretful war and “haunted public places until the late 1950s.”

While Murakami’s outlook focuses on the past and is relatable to the harshness of modern society, Sato’s on the other hand, is serene, forward looking and representative of what Japanese society should have been like. Sato embodies calmness and optimism that were needed during the postwar. When Murakami first meets Sato, Sato is in the middle of questioning the first suspect, the girlfriend of the gun dealer that gave Murakami’s colt to Yusa. He makes the interrogation seem like a relaxed conversation by offering the suspect cigarettes, talking nonchalantly, and smiling tranquilly. Compared to Murakami’s frantic search in the black market earlier, Sato is casual and composed. Once he finds out what he needs to know from the suspect, he goes and takes a nap in a cool part of the building, until Murakami comes back with info on the gun dealer. [xviii] While everyone else is continually beaten by the heat throughout the movie, Sato easily copes with it. In other words, while everyone else is overwhelmed by the post-war turmoil, Sato confidently looks towards the bright future. After Murakami returns with info on the gun dealer, Sato assures him that the case is almost done and compliments Murakami’s police work, even though Murakami confesses that his gun was used in the crime.

Sato’s forgiving nature and clear distinctions between good and evil also guides Murakami. Later in the investigation, right before they decide to call it a day Sato invites Murakami to his home. On the way, they walk on a country road and Sato tells Murakami that questioning is complicated, patience is key and strong arming suspects never works. Murakami listens to his advice intently as the sun behind them gently starts to set in the horizon of trees, a gentle breeze blows Murakami’s tie, and cicadas buzz faintly ambiently. [xix] Compared to the endless noise and movement of the black markets in the city, the country offers peace in the simple nature. They eventually approach the house and are warmly greeted by Sato’s wife and children, then over rationed beer and squash Sato comments that his house is nothing but a glorified shack, but Yusa’s place where they investigated earlier looked awful. Despite the rough situation, Sato is not embittered by it. He then says that maggots prefer filth, when Murakami interjects that he actually feels bad for Yusa and that bad situations create bad men. Sato replies that thinking that way will lead to delusions, and that “the bad guys are bad.” Sato upholds a clear distinction between good and bad, even though tragic for people like Yusa, Sato believes law and peace should be a priority over empathizing with criminals. When Murakami says he can’t bring himself to think like that, and that he almost went down the same destructive path when he got back from the war, Sato sympathetically listens and says that even though Murakami and Yusa are similar, they are entirely different because Murakami strives for goodness. Sato may not be sympathetic to criminals, but he is forgiving to people that make efforts to be good.

Sato’s forgiving nature and clear distinctions between good and evil also guides Murakami. Later in the investigation, right before they decide to call it a day Sato invites Murakami to his home. On the way, they walk on a country road and Sato tells Murakami that questioning is complicated, patience is key and strong arming suspects never works. Murakami listens to his advice intently as the sun behind them gently starts to set in the horizon of trees, a gentle breeze blows Murakami’s tie, and cicadas buzz faintly ambiently. [xix] Compared to the endless noise and movement of the black markets in the city, the country offers peace in the simple nature. They eventually approach the house and are warmly greeted by Sato’s wife and children, then over rationed beer and squash Sato comments that his house is nothing but a glorified shack, but Yusa’s place where they investigated earlier looked awful. Despite the rough situation, Sato is not embittered by it. He then says that maggots prefer filth, when Murakami interjects that he actually feels bad for Yusa and that bad situations create bad men. Sato replies that thinking that way will lead to delusions, and that “the bad guys are bad.” Sato upholds a clear distinction between good and bad, even though tragic for people like Yusa, Sato believes law and peace should be a priority over empathizing with criminals. When Murakami says he can’t bring himself to think like that, and that he almost went down the same destructive path when he got back from the war, Sato sympathetically listens and says that even though Murakami and Yusa are similar, they are entirely different because Murakami strives for goodness. Sato may not be sympathetic to criminals, but he is forgiving to people that make efforts to be good.

Sato’s mentor-like relationship with Murakami suggests the endless good that could have come from social outcasts being looked out for. In an incredibly similar instance a veteran wrote to Asahi newspaper that he owed his ability to stay out of crime during the post-war to his experience with a Sato-like figure. He accosted a young man on a dark street, intending to rob him, only to discover that he was assaulting an off-duty policeman. His story, as it turned out, had an uplifting ending. The policeman did not arrest him but gave him a hundred yen and some of his own clothing, while urging him to have faith in his ability to surmount his difficulties. Though the writer was still without wife or child or home or job or money, his letter was offered as a public vow that he would go straight thereafter. [xx]

Even though Murakami never tried to rob Sato, the police officer in the story and Sato are relentlessly optimistic, forgiving, and are almost pastoral. Both of their morals are grounded in reality and yet sort of spiritual since it hints at Buddhist sentiment to care for the weak and in the case of Sato, connects to Shintoism through the peace that “natural objects” project. [xxi] At the time in Japan, however, the Sato-type are uncommon since “there existed no strong tradition of responsibility toward strangers, or of unrequited philanthropy, or of tolerance or even genuine sympathy toward those who suffered misfortune” even though it was taught in religion. [xxii] Kurosawa suggests that perhaps if there were more people like Sato or this police officer the post war wouldn’t have been so tragic. Additionally, the formulation of the black markets or upsurge in organized crime might not have been as dramatic. Maybe the illicit arms market would be smaller, rice ration cards wouldn’t be treated like currency, or police wouldn’t have to ask for help from the yakuza. After all, the repressed fuelled these markets.

Nevertheless, the tragedy Kurosawa highlights is the infeasible possibility that there could be so many caring people like Sato and the never ending chase after crime. Kurosawa expresses the continual chase at the last scene of the movie when everything is wrapped up, Yusa is arrested, Murakami found his colt, and Sato is lying in a hospital bed talking to Murakami. Sato congratulates Murakami on his first citation and cooly encourages him to forget Yusa and not to hold on to the guilt of losing his gun. He continues to reflect on how he was equally sentimental during his first arrest but as time passed, he lost that feeling and just continued making arrests for the greater good. There’s no time to feel so sentimental when there’s countless criminals out there with good people they can prey on. [xxiii] For the few good guys it’s an endless chase after the countless bad guys.

Nevertheless, the tragedy Kurosawa highlights is the infeasible possibility that there could be so many caring people like Sato and the never ending chase after crime. Kurosawa expresses the continual chase at the last scene of the movie when everything is wrapped up, Yusa is arrested, Murakami found his colt, and Sato is lying in a hospital bed talking to Murakami. Sato congratulates Murakami on his first citation and cooly encourages him to forget Yusa and not to hold on to the guilt of losing his gun. He continues to reflect on how he was equally sentimental during his first arrest but as time passed, he lost that feeling and just continued making arrests for the greater good. There’s no time to feel so sentimental when there’s countless criminals out there with good people they can prey on. [xxiii] For the few good guys it’s an endless chase after the countless bad guys.

The neverending surge of crime Sato describes raises the question of black markets in Japan’s present and future. From the constantly moving black markets, Japan eventually turned into “the world’s most extensive concrete jungle” where crime can flourish. [xxiv] Especially the yakuza have thrived, particularly in “gambling, prostitution, and trafficking in methamphetamine” and even have small operations in Hawaii. [xxv] In addition to traditional criminal activities, they have some control over the entertainment industry like ties to talent agencies, the nuclear industry, and construction operations. On top of that, the Japanese police force is still said to be “incompetent” in dealing with yakuza-related crime, due to the power the yakuza have over countless industries. [xxvi] However, while during the postwar the black markets that the yakuza controlled were a necessity for daily life, there’s little demand anymore for so many black market items. Also, aside from the yakuza, petty crimes are almost nonexistent in Japan now. Despite the prevalence of a few large black markets run by yakuza, Japan effectively cut down crime exponentially. Even though Sato-like people are few, maybe there is truth in his optimism that good will overcome evil.

Even though on the surface Akira Kurosawa’s Stray Dog seems like a standard detective story, its characters are full of insight and claims on the frantic environment of post-war Japan. In particular Murakami represents the ways Japan dealt with black markets and personifies Japan as country dealing with identity crisis, trauma, neglect. On the other hand, Sato symbolized a sort of wise mentor, representative of the few people that gave hope and helped the repressed. Overall, even though the post war was tragic, Sato’s optimistic outlook with the decreased necessity of black markets in Japan proposes the hopeful future of Japan.

Even though on the surface Akira Kurosawa’s Stray Dog seems like a standard detective story, its characters are full of insight and claims on the frantic environment of post-war Japan. In particular Murakami represents the ways Japan dealt with black markets and personifies Japan as country dealing with identity crisis, trauma, neglect. On the other hand, Sato symbolized a sort of wise mentor, representative of the few people that gave hope and helped the repressed. Overall, even though the post war was tragic, Sato’s optimistic outlook with the decreased necessity of black markets in Japan proposes the hopeful future of Japan.

Notes

[i] Stray Dog. Dir. Akira Kurosawa. Perf. Toshiro Mifune, and Takashi Shimura. Toho, 1949. Kanopy. Web. 19 September 2018.

[ii] Owen Griffiths, “Need, Greed, and Protest in Japan’s Black Market, 1938-1949” Journal of Social History (2002). 1.

[iii] Stray Dog.

[iv] John W. Dower. Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Wake of World War II. W.W. Norton, 1999. 60.

[v] Chris Fujiwara, “Excess in Stray Dog” The Criterion Collection (2004).

[vi] Dower. 144.

[vii] Dower. 145.

[viii] Terrence Rafferty, “Stray Dog: Kurosawa Comes of Age” The Criterion Collection (2004).

[ix] Dower. 139.

[x] Kenneth Kurihara, “Post-War Inflation and Fiscal-Monetary Policy in Japan” The American Economic Review (1946). 847.

[xi] Kurihara. 846.

[xii]Jake Adelstein, “The Yakuza: Inside Japan’s Murky Criminal Underworld” CNN (2015).

[xiii]Lt. Bruce A Gragert, “Yakuza: The Warlords of Japanese Organized Crime” Annuel Survey of International & Comparative Law (1997). 154.

[xiv] Dower. 144.

[xv] Stray Dog.

[xvi] Dower. 60.

[xvii] Dower. 61.

[xviii] Stray Dog.

[xix] Stray Dog.

[xx] Dower. 60-61.

[xxi] Dr. Carmen Blacker, “Shinto and the Sacred Dimension of Nature” Shinto and Japanese Culture (2003).

[xxii] Dower. 61.

[xxiii] Stray Dog.

[xxiv] Misha Glenny. McMafia. Vintage Books, 2008. 289.

[xxv] Adelstein.

[xxvi] Glenny. 291

Bibliography