12 Anger or Laughter? The Dialectics of Response to The Birth of a Nation

Chuck Kleinhans

In 1980, Spike Lee made a twenty-minute film as his first-year MFA project at New York University (NYU). The film, titled The Answer, was an angry response to The Birth of a Nation, and it caused controversy.[1] The film depicts an unemployed black screenwriter/director who agrees to write and direct a remake of D. W. Griffith’s famous 1915 work. But when he realizes he can’t do it, his decision prompts the Ku Klux Klan to burn a cross on his lawn. The final image shows the writer running out, knife in hand, to confront the racists. Lee states that, in his time at NYU, The Birth of a Nation was taught as a masterpiece, and, most pertinently and egregiously, the faculty validated it but never mentioned that the film promoted a Ku Klux Klan revival that directly contributed to the lynching of many black people. The Answer obviously prefigures Lee’s satiric feature Bamboozled (2000), in which black creative media folks produce a program based in buffoonish racist stereotypes, which turns out to be, against their plans, spectacularly successful.

I explore two aspects of this situation, using it as the hinge of a diptych to consider, on one side, the critical standing of Griffith’s epic, which has stirred angry responses since it was first exhibited, and, on the other side, comic satiric responses to the film, the Ku Klux Klan, and contemporary media racism. In addition to dividing the essay in this way, I use the endnotes to create another layer of critical commentary. Thus, a relatively fluid and quick discourse in the main body will be complicated and elaborated by a different layer of consideration.

One: The Birth of a Nation at Fifty in Bloomington, Indiana

My Blu-ray copy of The Birth of a Nation has the following promotion tag on the back cover: “One of the greatest American movies of all time!”[2] I dispute that. While greatest is obviously a flexible and highly subjective term, and easily recognized by most Americans over a certain age as advertising hyperbole, it remains widely used and granted at least passive consent in art criticism. I want to ask why the term can be used so casually and to point out the political and ideological flaw in still using it. I suggest that we simply laugh at The Birth of a Nation and dismiss this pretension of its universal quality.

I say this not to be critical of the historical research that has been done on the film. Historical research into the text itself and into the film’s context and reception is absolutely useful, necessary, and important. Nor do I argue that the film is not significant in film history for its often-noted innovations: feature length, epic spectacle, road-show presentation, intervention in popular imagining of history, and (some) changes in acting style and narrative crosscutting. The fact is that it was (more or less) the first film to bring these elements together.

What I address here is different: Is this precise film in any way meaningful (or threatening) in the United States today? Does it deserve an angry response? And my answer to both questions is no. The film is laughable, and it is worth dismissing by ridicule. I know that some people think the film is still dangerous, despicable, and worthy of censorship—or at least “trigger warnings.” But I hope to persuade them that The Birth of a Nation is long past its sell-by date as effective race propaganda. The world has moved on. Not that racism isn’t still a major issue and problem in the search for justice in the United States; but it is present and enacted and expressed and opposed in very different ways today. It is very present in the recent ebb and flow of 2016 presidential campaign politics, when issues involving race and nationality are being worked out in a diverse set of issues: police violence against black people, Islamophobia, deportation of undocumented immigrants, and so forth. In this larger framework, the residual issues of the US history of slavery, the Civil War, and the unfinished work of Reconstruction have a different nature and resonance. At its most visible, this racist nostalgia appears as the new lost cause of flying the Confederate battle flag and maintaining monuments and place names of the Confederacy. But that should not distract us from the central organizing goal of stopping police violence on black people in the short run and creating social and economic justice in the long run.

But I want to return to the term greatest and pull it apart a bit. How is it that such a racist film became commonly labeled “one of the greatest,” or a “masterpiece,” or a “landmark”? Of course, the film’s owners and promoters would understandably use such terms to attract the public to screenings. But how is it that the field of film studies has frequently fallen into the same pattern? To answer that question, I look not at the centennial of The Birth of a Nation but at the fiftieth anniversary, in 1965.

Several things were going on at that time that we might not be aware of today. First of all, many people who cared about film and film history at that point were old enough to have actually seen earlier screenings of the film, or to remember Griffith’s funeral in the immediate post–World War II era. And this actually makes a difference. In a time when people did not have ready and personal access to films of the past (as we do today with video recordings, DVDs, and streaming), they relied on their own knowledge and memory of screenings they had attended. This was the (perhaps golden) age of the film society—a nonprofit cultural enterprise, typically in college communities, organized to make important films from the past available as examples of film art.[3] And it was the dawn of the college-level film course, with the introductory courses usually organized around “masterpieces” and historical surveys of important films.

Today we can see the mid-1960s as a watershed moment in film studies.[4] An older generation had faced the uphill struggle of getting movies recognized as an authentic art. Largely they did this by evoking an old-fashioned rhetoric of art world concerns, which admitted that, in literary critic Edmund Wilson’s terms, there were “classics and commercials,” and that most cinema fell in the latter camp. But, the proponents argued, some films were indeed art, and masterpieces, modern classics. Thus, a canon of worthy works was a major articulation of this belief.[5]

As film studies expanded in the 1960s, moving from the former platform of journalistic film reviewing to the prospects of the academy, the older model was revised in terms of slightly different norms. To establish film within the academy, the field had to face the already validated arts, particularly literature and visual arts, and make a convincing case that film (1) was an art form unto itself, (2) contained important works, and (3) was made by recognized artists. The doctrine of authorship provided an important scaffolding to this construction. Against the fact that feature narrative film was very much an industrial product, financed as an entertainment business, aimed at making a profit, and based in a collaborative art process, authorship allowed for genius or master artists. D. W. Griffith was easily interpreted in this way because he had achieved notable works over a long span of time. He had also clearly advanced cinematic narration and drama in a sequential pattern that showed development. In this frame, The Birth of a Nation was validated as not just a major or notable work (which it certainly is in Griffith’s career) but with the attached honor of being a masterpiece or classic—that is, as art. Understanding this casual slide from one category to another and receiving validation in the process depends on sorting out several factors.

First, there is a confusion between historical development and art. Art history, in particular, has tended to project an evolutionary model of aesthetics. Each successive art movement was taught as facing and overcoming and transcending the limits of the previous age or movement. The same pattern (though to a lesser degree in actual practice) was apparent in literary history. It is thus easy to see why the technologically dependent and narratively and performatively shaped development of cinema would be read as one based in progress, in an evolutionary or developmental model. The Birth of a Nation clearly is a big step up from Griffith’s earlier biograph films. But is that formal change one that produces an increase in art?

That depends on how we understand art, and the set of dominant assumptions about art in the intellectual milieu of the mid-1960s was different than the general consensus today. We are now on the other side of the art/society divide. The effect of the Cold War on US cultural and intellectual life was to validate a formalist and rather pure Kantian ideal of what constituted art—divorced from the social, the political, the historical. This formalist choice to regard the artwork as separate from its social origins and social effects allowed for the validation of a remarkable and fairly complex text such as The Birth of a Nation as a distinct and valuable artwork, linked to its creator/author but divorced from its political agenda and social effect, and from real audiences.

Of course, actual screenings of The Birth of a Nation in the museum, cinematheque, film series, or classroom framework almost always included some notice of and apology for the film’s extreme racism (or at least this was the case in the North).[6] But discussion of the film, especially by those who were teaching it in the college curriculum, almost always oscillated between saying the film was racist but historically important (though that “history” was often taken as meaning history of cinema rather than political or cultural history) and saying it was a major work of cinematic art (with art understood in the Kantian sense of disinterested and autonomous appreciation).[7] In contrast, consider the measure that Spike Lee bluntly used in his NYU experience: “Well, they never talked about how this film was used as a recruiting tool for the Klan and responsible for Black people getting lynched.”[8]

My own approach to this is deeply embedded in my personal history in terms of film studies and the progress of civil rights in the 1960s.[9] Thus, it was especially interesting to me that the instigating event for this essay, a conference on the film’s centenary, took place at Indiana University in Bloomington, where I arrived in fall 1966 to pursue graduate work in comparative literature. It just so happened that comparative literature was the home of film studies at the university at the time, with leading roles played by professors Harry Geduld, Ron Gottesman, and Charles Eckert.[10] And early on, they addressed Griffith and The Birth of a Nation—most notably in the then pioneering series of “Focus On” handbooks, which included Geduld’s Focus on D. W. Griffith (1971) and, commissioned by Geduld and Gottesman, Fred Silva’s Focus on The Birth of a Nation (1971).[11]

Geduld first mentions The Birth of a Nation as Griffith’s “most controversial film” without specifying what the controversy was. A few paragraphs later, the film is mentioned as “his greatest commercial and (arguably) his greatest artistic triumph.” The book’s critical commentary section begins with the director’s wife’s account of how the film was made, an excerpt from Nicholas Vardac’s book on the transition from stage to screen emphasizing cinematic technique, a second article on technique, and then an assortment of negative criticisms of the film from a National Association for the Advancement of Colored People pamphlet of the time. So the volume definitely recognizes the controversy surrounding the film. Geduld’s way of handling (or finessing, some might say) the matter is to summarize the film in the antepenultimate and penultimate paragraphs of his introduction as: “the first film to reveal the vast potentialities of the motion picture as a vehicle for propaganda. It was the first film to be taken seriously as a political statement and it has never failed to be regarded seriously as a ‘sociological document.’ . . . The Birth of a Nation, while it heightened a perversion of history and the dogma of racism to the level of art, also indicated the rich possibilities inherent in applying the techniques of the motion picture to the imaginative interpretation of documentary material.”[12] Personally, the phrasing is too delicate for me, because I dispute the argument of “art,” but inescapably Geduld acknowledges the problem, as would any thinking academic in the civil rights era. But the book’s back cover blurb still identifies the film as a “classic” (in quotation marks).

Silva’s introduction to Focus on The Birth of a Nation uses a similar rhetoric. He refers to seeing “Griffith’s masterwork not only as an outmoded, biased account of Reconstruction, filled with unquestionably racist attitudes, but as a genuine cinematic achievement.” And, although he asks the question, “Can a work of art be judged successful apart from its content?” he implicitly answers it by assuming such a separation is possible.[13] He also repeatedly returns to excuses for the white South: “Griffith presented the values of a conquered people who viewed the rubble of what they had conceived as a civilized, moral way of life. The permanent values of the land, the humanistic possibilities of the aristocracy, the importance of place, the tragic impact of the Civil War, and the heightened sense of melodrama.” Most glaringly, Silva expresses concern for the white South (“conquered”) while utterly ignoring the black South (most obviously and literally freed, granted human status and civil rights). This kind of rhetorical slippage can seldom go unremarked on today.[14]

Race in Bloomington

In addition to thinking of The Birth of a Nation in relation to the emergence of academic film studies and the notable pioneering work done at Indiana University in the era of the film’s fiftieth anniversary, it is worthwhile to think about the situation of race relations in Bloomington and at Indiana University at that time. After all, knowledge is always situated. What was the situation in the mid-1960s?

When I arrived as a graduate student in comparative literature in 1966, the campus was only a few years beyond finally integrating the barber shop in the Memorial Union so that African American students could get their hair cut there, and “reserved” signs in the large student union cafeteria were finally removed, allowing black students to sit anywhere in the space. Frankly, Bloomington was much more a “mid-Southern” environment than a Northern one. Although Indiana University had one of the first Afro-American studies programs in the United States, the university faculty and student body in no way reflected the demographics of the state of Indiana. Only through direct student agitation and action was change initiated: a long paper by the radical left Students for a Democratic Society documented racial exclusion in the fraternity and sorority system. Subsequently, black athletes on the football team made demands and conducted a boycott, resulting in a losing season for the team and a win for progressive change as the administration insisted that the Greek system remove its exclusion clauses.[15] Similarly, a sit-in by the Afro-American student organization blocking the pending “Little 500” bike race in 1968 and a further blockading of Ballantine Hall during negotiations with administrators produced some major positive changes, including expanded admissions of African American students.[16]

However, such progress was balanced by the daily discrimination black people faced in Bloomington. Robert Johnson, a sociology graduate student and head of the Afro-American student group, was repeatedly threatened with firearms and attempts to run him off the road when driving around town with his white girlfriend. The Klan was an active presence, even filing for a permit for a major demonstration (which was denied due to a judge’s conclusion that it would likely lead to a violent confrontation). Nearby Martinsville, on the main highway halfway to Indianapolis, had been a stronghold of the Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s and 1930s and was well known as a town where black people could not stop to buy gas for their cars.[17] In 1968, a black woman selling encyclopedias door-to-door there was stabbed to death. In Bloomington, a small Afrocentric store, Black Market, opened up on Kirkwood Avenue in 1969 and was firebombed over the Christmas break. Professor Orlando Taylor, the head of Afro-American studies, was arrested for participation in the Ballantine Hall affair along with activist students and subsequently left the university.[18]

In this context, it’s possible to understand why The Birth of a Nation could be shown on campus in classrooms and in film club screenings with only the most token acknowledgement of the film’s racism. It was an ongoing struggle to have African and African American perspectives in the curriculum and in the classroom.[19] So, another fifty years later, we can measure some progress in discussing the politics of The Birth of a Nation at a conference on campus. The Klan seems to have disappeared from Bloomington, though local racist incidents still occur—such as a sophomore yelling “white power” while trying to forcibly remove a Muslim woman’s hijab in fall 2015. And given the opportunity, my taxi driver, while taking me from the campus site to the hotel for visiting attendees, frankly voiced his racism and xenophobia toward the recent surge of Chinese students at the university along with some mundane anti-Semitism.

In summary, the motivation to professionalize and academicize film studies combined with other factors to override the logical intellectual extension of the pragmatic world of the US civil rights era into intellectual life for most liberal and all conservative intellectuals of the period. Only the radicals and activists attempted to move the fulcrum point. The first major academic study of The Birth of a Nation appeared in 1964, a special ninety-five-page issue of Film Culture publishing the erstwhile efforts of Seymour Stern, who had a hagiographic approach to Griffith. Stern was also a vehement denier of any racism in the film or in the director himself, having carried on since the early 1940s a vendetta against “communists” who critiqued the film’s politics and (according to Stern and others) ran the Film Department at the Museum of Modern Art.[20] Thus, a virulently racist film could be easily passed off as “one of the greatest,” “a masterpiece,” “a classic.”

Two: Laughing at The Birth of a Nation

Today it’s easy to understand Spike Lee’s anger at The Birth of a Nation’s critical reputation as a prestigious work at NYU in 1980. Lip service liberalism rested on several factors: the historical delay created by generational difference; stunted development of the film studies field, which had been distorted by the effects of postwar anti-leftism in the academy and cultural circles; and a confusion of the film’s historical position with its aesthetic and cultural value. Since then, things have changed. The Ku Klux Klan is a fragmented shadow of what it was in the 1920s, sometimes appearing in headlines as a shorthand but insignificant as a player in white supremacist activity and a general right-wing racism. In terms of media image, the visual embodiment of race in The Birth of a Nation is now totally out of date, to the point of being discredited and laughable. One mark of that is today’s active satiric ridicule of the Klan and of distended old-school racism. Visual culture has changed, and cultural norms and expectations have changed as well. In today’s contested terrain, racism is unquestionably present, but it takes different cultural forms, and this fact makes Griffith’s film a ridiculous relic. My charge against The Birth of a Nation in today’s world is that the film is laughable due to its antiquated acting style, its extreme prejudice about African Americans and Southern white womanhood, and its melodramatic staging of battlefield bromance.

In terms of actor performance, the film’s histrionic and presentational acting style is so foreign to today’s audience that almost everyone’s reaction can only be distanced, alienated, and unsympathetic (which directly contravenes the film’s goals of heroic spectacle and melodramatic pathos). I acknowledge the excellent work that has been done in specifying the gradual development of acting style from nineteenth-century stage melodrama to early dramatic film and the move toward what we now call the classic narrative film of the 1920s.[21] But I would note that when figures such as Tom Gunning, Ben Brewster and Lea Jacobs, and Roberta Pearson make their case about the “maturation” of acting style or its increasing realism (relative to what preceded it), this is true of the narrow and finely examined time-specific progression they address. But that doesn’t make The Birth of a Nation transparently readable or even “gradually adaptable” a century after its premiere.[22]

Shifts in cultural perception make the film’s foundational attitudes grossly offensive to ordinary viewers. I will only sketch the most obviously cringe-worthy aspects here. First, all the film’s depictions of African Americans are instantly recognized as racist: happy field slaves, docile house slaves, inherently evil mulattoes, rampaging uniformed soldiers, and menacing rapists. I am not saying we are in a postracial era; rather, I assert that the visual culture representations of black people have decisively changed. The blackface images in The Birth of a Nation and the minstrelsy presentation of actual African Americans present in the film are today blatantly marked as absurd and dated, fit only for ironic scorn. This current view is the result of numerous factors, such as the presence of star athletes in major sports; the importance of African Americans in the entertainment industry, especially music, and entertainment media; and, of course, the presidency of Barack Obama. Black “positive images” exist now in the general (and mostly white) public consciousness in a way they didn’t a few decades ago. This is not to say that racist images of blacks don’t still appear, only that they are different.

Further, Griffith’s images of helpless females linked to a cult of virginity have no credibility. In a time of the female action hero, decades of final girl characters, and even child-marketed self-willed girls and princesses, no one can transparently accept the film’s premises about Southern white womanhood. Those assumptions, part of a strange psychosexual pattern in Griffith’s creative output (as well as in his personal life, it seems), were out of date when the film was released.[23] And they only became more out of touch over time, never matching the mainstream of twentieth-century girlhood and young adulthood in the United States. By the time of World War II, the meme of Southern white womanhood decisively changed in the popular imagination, as seen in the film version of Gone with the Wind (dir. Victor Fleming, 1939). Scarlet O’Hara’s transformation from superficial girl to determined, self-willed woman shifted mass understanding of the Southern belle while maintaining, to be sure, the narrative and trope’s saturated racism (discussed below). Today, as the United States approaches “majority minority” demographic shifts, finds biracial and multiracial families and individuals unremarkable—at least in urban areas and certainly in the mass media—and demonstrates clear changes in generational attitudes to interracial personal relations, few can accept the film’s hysterical racist fears.

Finally, the bromance of North and South, climaxing in the battlefield death scene of Tod Stoneman and Duke Cameron dying in each other’s arms, goes on so long that the “comrades in death” scene not only invites but emphatically underlines a homoerotic subtext, unspeakable in 1915 but obvious today. Griffith’s masculinist sentimentalism becomes grotesque and thus laughable.

Similarly, the narrative device of last-minute rescue remains a staple of Hollywood action melodrama, but The Birth of a Nation’s version of the Klan riding to salvation for whites and pure vengeance seems grossly unrealistic.[24]

Mocking the Klan

We live in a time of expansive satiric and ironic humor political commentary. Following on the long run of The Daily Show with Jon Stewart and The Colbert Report, combined with the expansion of YouTube in the millennium years, snark has become the common currency of political discourse, even extending its vulgar forms into the Republican Party’s presidential candidate debates in 2015–2016. Who would have foreseen Donald Trump asserting his penis was a good size in a national televised debate after a rival ridiculed Trump’s “short fingers”?[25] In a similar vein, news in February and March 2016 that the best known former KKK leader endorsed Trump, who in turn stalled on rejecting the gesture, brought forward a new round of comic satire mocking the Klan as did, for example, a Saturday Night Live fake commercial.[26] Various “Voters for Trump” extoll their candidate with a final reveal of what they’ve been up to: painting “White Power” on the side of a building, ironing a Klan robe, and gathering wood for a Klan cross burning.

Another example of humor undermining white racism appears in O Brother, Where Art Thou? (dirs. Ethan and Joel Coen, 2000). After earlier adventures and mishaps, the three white escaped-convict heroes stumble upon a Ku Klux Klan lynching. They spot the victim as a black musician friend whom they had met earlier. Determined to save the musician, they intervene and run off, in the process killing an earlier adversary. The Coen brothers present a nighttime cross burning and the Klansmen in rigid formation, itself a cinematic echo of Leni Riefenstahl’s interpretation of Hitler’s Nuremberg rallies. In a classic set of revealed and mistaken identities, “the boys” are read as black when they are revealed at the rally because their faces are covered with dirt from the previous scene. The Klan leader is shown as none other than Stokes, the “reform” candidate for governor, and their previous nemesis, Big Dan, exposes them (fig. 12.1). Running off with their buddy, the boys throw the Confederate battle flag high in the air. With the leader’s cry of “Don’t let that flag touch the ground” (the mark of defeat in battle), Big Dan steps forward and heroically catches the flagpole with his bare hands. Triumphant in his achievement, the moment is short-lived when the boys cut the cable holding the giant burning cross, which then falls on the hero.

In the next scene, at a political rally for the incumbent candidate Menelaus “Pappy” O’Daniel, his opponent Stokes arrives and explains that he was just at the failed lynching. He is undercut by the boys, who are performing live “Man of Constant Sorrow,” which, unbeknownst to them, had become a hit recording with constant airplay. In a double-recognition scene, The Klan leader spots the musicians as the “miscegenators” who ruined the lynching, and he tries to rally the crowd against them. But those present defy the Klansman because they love the Soggy Bottom Boys’ music, and they ride the Klansman out of town on a rail. Popular culture art triumphs over racism.

The Klan was ridiculed in the first episode of the first season of Chappelle’s Show on Comedy Central in 2003. Dave Chappelle performed his most notorious sketch, a mock PBS Frontline investigative documentary depicting Clayton Bigsby (Chappelle), a secretive white supremacist author (fig. 12.2). When the Frontline team arrives to interview the recluse, they discover he is a black man, blind since birth, raised in a Southern school for the blind in which he was told he was white. Having imbibed environmental racism, Bigsby spouts the most jingoistic slogans of white power and racist ranting. The film crew follows him to a book signing for his new volume. Along the way, they stop for gas at a rural outpost where a gang of white good old boys try to intimidate Bigsby because he is black, but uncomprehending, he joins in their racism. Next, Bigsby’s vehicle pulls alongside some white teens in a convertible playing loud hip-hop music, and he yells at them to turn off the music. “Did he just call us niggers?” one guy exclaims, and they erupt in celebratory high-fiving. Arriving at the meeting, Bigsby dons a Klan robe and hood and appears before his supporters calling for “white power.” When one of Bigsby’s most enthusiastic followers asks him to remove the hood so they can see their hero, he does so. The reveal stuns the audience. One fellow’s head explodes. The report ends with the deadpan observation that Bigsby did finally accept his identity as an African American, but then divorced his wife of nineteen years “because she was a nigger lover.”

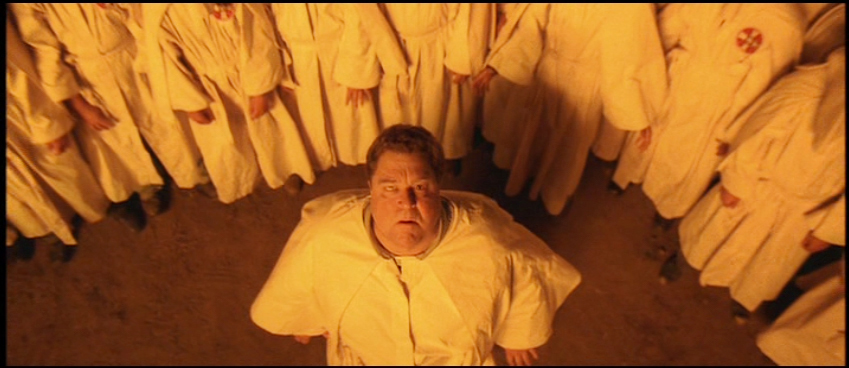

Quentin Tarantino inserted an anachronistic sequence in this 2012 feature Django Unchained, set just before the Civil War. After the bounty hunter pair, white King Schultz and freed slave Django, murder three outlaws who worked as overseers, the plantation owner hunts them down and conducts a night-rider raid on their wagon. The sequence presents both hard-charge riding and flashbacks to the initial assembly. In a characteristic Tarantino scene, that gathering shows men pointlessly arguing about the sacks they will wear over their heads: whether they fit, that the poor eyeholes obscure their vision, that they are badly made, and so on (fig. 12.3). The vigilante gang appears petty, laughable, and inept, not fearsome and bold. The point is sealed when they surround the wagon and Shultz detonates an explosive charge, killing and injuring the night riders.[27]

In a short sketch from the Comedy Central show Key and Peele, the African American pair are strolling in a park when a blond woman’s small terrier aggressively barks at them (fig. 12.4).[28] The woman apologetically explains that this is her new shelter dog that goes after all dark-skinned people. Key smiles and nods, saying they are not offended because “we can’t know what the dog has been through.” Cut to a year earlier, and the dog is revealed as the leader at a Klan cross burning, barking out “white power!” in subtitles (fig. 12.5).

These four examples show the ability of comedians today to mock and dismiss the Ku Klux Klan, significantly without dismissing racism itself. They are not asserting that we have reached a postracial plateau. Rather, they neatly maneuver and make the menace look ridiculous. But it is important to understand that this tactic depends on the vastly decreased prestige and power of the Klan, the foolishness of the group’s costumes and self-aggrandizing righteousness, and the critical distance that today’s audience has from the Klan.[29] The move depends on a formal shift, a distance, and a critical separation that allows for snarky wit. And it’s not always possible to achieve that.

A case in point: a sketch from the final season of Key and Peele in 2015, in the wake of notorious police assaults on and shooting of black men. Key, in whiteface, plays a trigger-happy cop who shoots black men he encounters: a guy holding a Popsicle and so forth. Finally, the black chief of police, played by Peele, arrives on the scene, where Key is explaining his murders as excusable mistakes. Key sees the chief, pulls out his gun, and shoots him, again excusing the “mistake.” The sketch is too true to be funny. The performers were no doubt completely aware of this—“too soon,” as the world of professional comedy would say. Which underlines the point that a gap is needed for effective satire. This sketch has outrage but no laughs (nor should it).[30]

Another example of the gradual evolution of social norms and understanding that underlines The Birth of a Nation’s racist imagination can be identified when we recognize that satiric ironic humor always has power only in relation to the social space and time in which it appears or reappears. Things have changed, for example, since The Birth of a Nation’s fierce images of a black man menacing a Southern white woman, as is evident in the notorious example of Kanye West’s 2009 interruption of Taylor Swift’s acceptance speech for best female video at the MTV Video Music Awards ceremony.[31] It was an initially serious moment in which West went onstage, took the microphone away from Swift, and then claimed the award should have gone to Beyoncé: “I’m sorry, but Beyoncé had one of the best videos of all time!” The episode has become a standard joke about Kanye’s overinflated ego and sense of masculine privilege. Several years later, Swift (or more likely someone faking her) managed a neatly snarky retort when Kim Kardashian gave birth to West’s child by tweeting: “Yo I’m happy for you imam let you finish but Beyonce had one of the best labors of all time.”[32]

An Emerging Form

Today, while a general discussion is taking place regarding youth’s presumed narcissism especially framed by new digital social media technologies, another activity is emerging. These new platforms and devices increase the possibilities of grassroots communication and thus increase the potential for dissenting and critical voices to be heard. I’m referring to the online world of YouTube, bloggers, and the remarkable presence of people making strong antiracist statements in a snarky comic form.[33] Particularly with the growth and development of the Black Lives Matter movement, there is a wider range of dissenting and activist discourse especially by black women. Much of this is very serious, very political, and often polemical, but an important part of this discourse frequently uses sarcastic comedy. One example: one of the best known moments of the 1939 film Gone with the Wind is Scarlett O’Hara’s confrontation with Prissy. Scarlett’s cousin Melanie goes into premature labor during the Atlanta campaign. Scarlett, in hysteric mode, tells the slave servant to get the doctor, but Prissy fears the dead, dying, and injured at the field hospital and doesn’t carry out the errand. On the servant’s return, Scarlett realizes she will have to go. The scene of her arrival provides a major turning point: the Confederacy is clearly doomed with so many casualties, the doctor must tend them, and Scarlett realizes she will have to take control. On returning to the house, she orders Prissy to prepare for the imminent birth only to hear the slave’s famous line, “I don’t know nothin’ about birthin’ babies!” Scarlett then slaps Prissy.

The moment has been reproduced in mash ups and other forms.[34] YouTube comments often include arguments. A basic racist response claims Prissy is stupid (or “retarded”). But there’s also an incredibly sharp and sarcastic response that celebrates Prissy’s self-election out of the dilemmas of white women dealing with imminent pregnancy. One of these responses, by YouTube user TheAdelaidehall, states: “Melanie is moaning & groaning in painful agony, Scarlett is so stupid she believes Prissy can ‘birth babies’, Prissy takes her time, sings & quite frankly doesn’t give a damn about either of those two white bitches . . . I call that attitude! Go Girl! (Love Prissy).”

I argue that in terms of style, presentation, and overt politics, The Birth of a Nation is no longer effective race and gender propaganda. Thus, we don’t need to fear it. Anger is not the best response; dismissive laughter is. But on a deeper and underlying level, the film did speak to and of and for white anxieties (through the entire class range) about twentieth-century modernity. And those psychic formations rest in material conditions that have only become more accelerated in our current neoliberal era.

Among the distresses of twentieth-century modernity dramatized in The Birth of a Nation are the destructive force of war on combatants and civilians; economic collapse; the middle classes losing ground; and the immense expansion of state power and state legitimization witnessed in bureaucratization, large-scale surveillance of individuals, and a feeling that the state, a distant state (today called Washington, DC), controls our lives. Surveillance is not just the National Security Agency’s collection of internet and phone data but also in trigger warnings and admonitions about appropriate Halloween costumes or “check your privilege” remarks. Added to this is the privatization of life caused by capitalist social organization with the commercialization of private life and runaway expansion of consumer culture. All this is experienced as the collapse of traditional cultural and moral hierarchies. Thus, the appeal of nostalgia: “Make America Great Again.” The three-period division of The Birth of a Nation dramatizes this theme: a pastoral antebellum South that is prosperous and ordered; the disorder and conflict of the Civil War and its aftermath; and the conflicted end of Reconstruction and a return to the ordered past.

These broader ideological formations are still with us as witnessed in the 2016 presidential campaigns. They also appear in various specific conversations, such as debates over women’s reproductive health rights, including abortion; in arguments on gun violence and regulation; and in discussions of police violence against minorities. We are in the process of an epistemic shift. We might call this a postmodern sensibility in which there is, to use one example, a lack of confidence in authority. But this cuts both left and right in its result. The right looks to simple slogans voiced by humorless dogmatic speakers. And it calls on nostalgia for an imaginary past. The left looks a different way: toward a progressive and expansive future, sometimes sloganeering, but often ironic. That gap provides the ground for a conflicting negotiation: mockery, snark, and sarcastic satire flourish in this evolving field. Without easy access to the levers of power, speaking truth, even if rueful or ironic, remains a democratic option. Thus we return to the perennial issue of comic satire: Is it subversive or adaptive? And the answer is, it is always contingent, always based in the specific intersection of text, context, and audience.

On this ground we see in The Birth of a Nation a racist nostalgia for an ordered past depicted as the happy plantation life of the antebellum South. The Civil War then becomes the turning point, and Reconstruction embodies all the fearful anxieties, such as Northern carpetbaggers running the government and imposing laws. Lives are controlled by seemingly arbitrary or corrupt state decrees (surely the basis for the vast grassroots support for Kim Davis in summer 2015)[35] as bedrock ideological formations such as heteronormativity seem overthrown. In the film, changed power relations are presented as disorder and pose the most danger to Southern white womanhood in the two dramatic cases of Gus and Little Sister and the cabin scene. Within the film, the rise of the Ku Klux Klan is seen as the only solution to the disorder. While a grassroots vigilante mass movement of night riders is no longer plausible, certainly we see considerable acceptance among a significant number of US whites of militant, military, and sweeping violence—in the promised swift deportation of eleven million undocumented people and registration for US Muslims, as promised by Donald Trump in early 2017, and in the extralegal execution of Trayvon Martin by a self-appointed vigilante amateur cop and in the military-style police occupation of Ferguson, Missouri. These are not laughing matters. They summon us to action. And one handy tool to maintain a sensible balance in the struggle is using our comic sense.

Chuck Kleinhans was Associate Professor Emeritus of Radio/Television/Film at Northwestern University. He was Editor with Julia Lesage and John Hess of Jump Cut: A Review of Contemporary Media until his death in 2017.

- The film is not available for viewing. Lee and others have described it. The filmmaker has claimed variously that on viewing it as part of evaluating first-year students, the faculty voted to kick him out for disrespecting The Birth of a Nation. His version was disputed by faculty who said some teachers did want to weed out Lee, but others advocated for him and he was continued. They offer different reasons: that Lee was brash and obstreperous, that the film was an overreach of his skills at the time, and so forth. John Colapinto, “Outside Man: Spike Lee’s Unending Struggle,” New Yorker, September 22, 2008, 56–57. Cinema at NYU is divided into two departments. Lee was enrolled in the film production program. There was also a well-known and well-regarded film history and criticism program. It is not clear whether Lee is referring to faculty in both programs or which specific professors were involved. ↵

- The Birth of a Nation, directed by D. W. Griffith, Kino Classics 3-disc ed. (New York: Kino Lorber, 2011). The quote is attributed to the American Film Institute, and, although no specific source or author is given for the blurb, I have no reason not to take it at face value. To its credit, after this come-on, the following text describes the film as controversial and opposed by the NAACP from its premiere on. Of course, it remains testimony to the pervasive dismissal of concerns about racism that both institutions—the American Film Institute and the commercial distributor Kino Lorber—validate the film’s “greatness.” ↵

- A few museums and cinematheques should be mentioned here, such as New York’s Museum of Modern Art and Henri Langlois’s Paris Cinémathèque Française. In the United States, the Museum of Modern Art had the extraordinary significance of distributing films to the network of film societies in the postwar era. In the 1960s, The Birth of a Nation was available in 8 mm and Super 8 mm versions from Blackhawk Films, which served the amateur consumer market. These were typically shortened versions. ↵

- A useful survey of US and UK film studies is Lee Grieveson and Haidee Wasson, eds., Inventing Film Studies (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2008), which, unfortunately, ignores McCarthyism and Cold War ideology in shaping the field. An important historical perspective on the 1960s film discipline is found in the introductory chapter of Dana Polan, Scenes of Instruction: The Beginnings of the U.S. Study of Film (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007). ↵

- In general, in the US postwar era, conservatives tended to dismiss the entire range of mass culture for not matching their standards for “high art.” Liberals and leftists tended to split, with some deploring popular culture while others viewed it as a social phenomenon worth taking seriously or an expressive form linked to the popular consciousness, particularly with pop music and media connecting to youth and dissent. ↵

- Museum and film society screenings at this time typically included a page of program notes on the film—a framework that would include notice of the most offensive parts. I am not accounting here for the film’s screenings by Ku Klux Klan and similar white supremacist organizations that did use the film for propaganda purposes and recruiting. Tom Rice, White Robes, Silver Screens: Movies and the Making of the Ku Klux Klan (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2015), provides a detailed account of the Klan’s relation to the film in the first half of the twentieth century. Since the Klan did not have prints, it connected with the original and revival screenings for recruiting and promotion of the organization. I believe the film is no longer serviceable for that purpose, as I argue later in this essay. ↵

- For the brief against Kant, a thorough introduction is Pierre Bourdieu, Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgment of Taste, trans. Richard Nice (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 1984). ↵

- Spike Lee, interview with Pharrell Williams, “Spike Lee Shows NYU The Answer | Ep. 9 Part 1, Segment 4/4 ARTST TLK | Reserve Channel,” October 8, 2013, www.youtube.com/watch?v=4q5PX4joOyg. The remarks begin at six minutes into the segment, immediately after a naked blonde white woman serves beverages to the two black artists. ↵

- I should make it clear that, although I began teaching university film classes in the late 1970s, I never taught The Birth of a Nation. Partly this was because I seldom taught film history per se, and never the silent era. I have taught some of Griffith’s melodramas in classes on melodrama. Although teaching The Birth of a Nation can be the occasion for many “teachable moments” about its racist ideology, in general the film presents distinct problems in its epic length and in the need to create a fuller historical context of US history, particularly of slavery, the Civil War, and Reconstruction. Given the effective elision of these matters in the US high school curriculum, The Birth of a Nation needs much more framing and elaboration than other films of the era for the college classroom. So, for pragmatic pedagogical reasons, I wouldn’t include it in a survey film history class. Other Griffith films could serve the purpose. On the other hand, for a topic-focused course—on the history of racism in US cinema, for example, or the historical epic genre—it deserves a substantial consideration. Julia Lesage’s recent suggestion to teach the film after teaching 12 Years a Slave (2013) is an excellent strategy. ↵

- I knew all three, and became close friends with Eckert, but for various reasons I never actually took a film class. ↵

- Handbooks were an important critical and pedagogical tool in early film studies. They were useful and fairly inexpensive textbooks that brought together materials on films and filmmakers, sometimes scripts, often initial journalistic reviews, notable interviews, and later scholarly and critical commentary. The Focus On series combined biographical, critical, and historical approaches and provided a casebook collection—diverse essays around a common text such as a short story or critical essay supplemented by different critiques and commentaries—that could be the starting point for an undergraduate paper. It was designed to continue from the typical college introductory expository writing classes, which heavily used the casebook approach at the time. The all-in-one book was designed for the student to have basic materials for a compare-and-contrast essay that would develop his or her ability to study, evaluate, and balance different critical approaches to the same text. Commonplace in literature departments, the Focus On series was the first casebook publication designed for the film curriculum. ↵

- The separation of art from sociology was a standard Cold War ideological move and so common as to be generally unremarked. ↵

- It’s worth noting for today’s readers that the issue of reactionary content and art was widely discussed in terms of fascist and other problematic art by intellectuals in the postwar era by figures such as Sartre and de Beauvoir, and it continued in the work of Sontag on Leni Riefenstahl and Kristeva on Céline. The Frankfurt School and other Central European exiles and thinkers contributed to the discussion in looking back at Weimar Germany and in exploring the postwar question of art after the Holocaust. ↵

- Silva goes on to invoke various (white) Southern writers: the Southern Agrarians, William Faulkner, Robert Penn Warren, Allen Tate, and John Crowe Ransom. I’d argue (or hope) that today no intellectually honest critic could fail to not also mention a distinguished line of African American intellectual and literary figures who offer a quite contrasting view of US history and legacy. ↵

- The situation is more complex than my sketch here can indicate. Perhaps the best short summary is in Mary Ann Wynkoop, Dissent in the Heartland: The Sixties at Indiana University (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2002)—although as a participant at the time, I find it very thin and overly reliant on established press versions, official documents, and administrators as authorities. The grassroots experience and the activist side is not well represented. Some oral history has been collected but, again, mostly from the establishment point of view. I worked on the consecutive underground press papers of the era, The Spectator, No Spectators, and Common Sense, which provide an alternative view, as well as the local annual Disorientation pamphlet produced by the New Left–based New University Conference chapter. ↵

- Wynkoop tends to separate the antiwar left from the black movement, whereas I see them as running together with extensive informal ties. The Klan and other armed whites were a known presence in the area. Marching in an antiwar demonstration from campus to the courthouse square (where the draft board office was located), one could see white men brandishing guns on the roofs of buildings on Kirkwood Avenue. ↵

- Although it probably was not formally enacted into law, Martinsville was known as a “sundown” town—one in which any black person’s life was at risk after sundown. Discrimination there extended to anyone “different,” as hippies also discovered in trying to buy gas in Martinsville. ↵

- Taylor and the others were found innocent of the charges at trial years later. The Black Market firebomber was eventually apprehended and revealed as a member of the Ku Klux Klan, as was the Martinsville killer. With rampant hysteria in the Indiana legislature and drum beating by the Indianapolis newspapers, in the public eye there was no differentiation between student activism, African American, feminist, antiwar, counterculture, gay, and socialist movements. It was also true that progressive forces were so small in numbers that in order to have a party, all those different trends would mingle, unlike the bigger and more divided or sectarian fields of urban politics of the time. The campus did have the unusual situation of one year electing a member of the Black Panther Party as president of the student government with the head of Students for a Democratic Society elected as vice president. ↵

- Gottesman did make an effort, including Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man in his introductory survey of US literature course (and inviting me, an all-but-dissertation, to lecture on it for the class). Following Taylor’s departure, Robert Johnson was installed as interim chair of Afro-American studies, and he asked me to teach a special section of the comparative literature introductory course for black students arriving under the new “group” program. I hesitated, asking whether it wouldn’t be better to have a black teacher. He replied there was no one available, so wouldn’t it be better to have me teach it than to not have it offered? My department agreed with the plan, and I redesigned the content with African, Afro-Caribbean, and African American literature. ↵

- The details are explained in Janet Staiger, Interpreting Films: Studies in the Historical Reception of American Cinema (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1992), 134–152. It is also discussed in Melvyn Stokes, D. W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation: A History of “the Most Controversial Motion Picture of All Time” (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007), 254–258. I discuss the involvement of Stern’s contemporary in Chuck Kleinhans, “Theodore Huff: Historian and Filmmaker,” in Lovers of Cinema: The First American Avantgarde 1919–1945, ed. Jan-Christopher Horak (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1995), 180–204. In 1939, while working at the Museum of Modern Art, Huff prepared a shot-by-shot description of the entire film that circulated first in mimeograph and that was later, a decade after Huff’s death, turned into a museum publication: Theodore Huff, A Shot Analysis of D. W. Griffith’s “The Birth of a Nation” (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1961). It appears to be the first such detailed breakdown of a motion picture and thus helped institutionalize the film’s prestigious place in film studies. ↵

- The recognized histories are Tom Gunning, D. W. Griffith and the Origins of American Narrative Film: The Early Years at Biograph (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1991); Ben Brewster and Lea Jacobs, Theatre to Cinema: Stage Pictorialism and the Early Feature Film (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997); Roberta E. Pearson, Eloquent Gestures: The Transformation of Performance Style in the Griffith Biograph Films (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992). Their analyses are relative and incremental for the short span they study (at most a decade and a half). I am using the baseline of a century. ↵

- By “gradually adaptable,” I mean that the average audience could quickly learn the pertinent conventions and come to accept them. This viewer adaptation often works with films using a broad comic mode, such as Chaplin or Keaton, but it is impossible today for a serious dramatic or epic mode. The kind of acting we witness in The Birth of a Nation to ordinary viewers (who are not film buffs or professors of cinema fluent in the historic range of cinema) seems ludicrous. At best, such acting is accepted by the ordinary public in convivial recreations of nineteenth-century melodramas reenacted at tourist venues anchored in sentimental views of the US Western frontier and other archaic amusements. It might be possible for those predisposed to the film’s racism to read it as a historical docudrama, antiquated in form but presenting “what really happened.” ↵

- Michael Rogin argues that the film’s obsession with protecting white womanhood from African American men not only was directed at controlling black sexuality but also functioned at controlling white females. Michael Rogin, “‘The Sword Became a Flashing Vision’: D. W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation,” in Ronald Reagan, the Movie and Other Episodes in Political Demonology (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1987), 190–235. ↵

- From our more distant vantage point, we can see the direct descent from The Birth of a Nation’s cavalry charge and Klan riders to subsequent Hollywood Westerns with the US cavalry or sheriff’s posse riding to the rescue. But these tropes are dated with more psychological and lone-hero Westerns of recent decades. Perhaps the last big cinematic charge was Francis Ford Coppola’s air cavalry episode in Apocalypse Now (1979), itself a heavily ironic and satirically over-the-top scene. ↵

- Obviously, the precedent had been set nearly two decades earlier when Republicans promoted the Starr Report investigation of the Clinton-Lewinsky scandal with the final report, printed in almost every newspaper in the country, detailing oral sex, ejaculate on clothing, and penetration with cigars in the Oval Office. Suddenly a generation of middle-schoolers became intensely aware of fellatio and manual stimulation as commonplace erotic activity with the widely noted result that teen boys were now expecting girls to perform fellatio. ↵

- “Voters for Trump Ad,” Saturday Night Live, March 6, 2016, www.youtube.com/watch?v=Qg0pO9VG1J8. Opening the same show was a parody of Trump defending his penis size in “CNN Election Center Cold Open,” Saturday Night Live, www.youtube.com/watch?v=Y1hEyiE2q-w. ↵

- In an interview, Tarantino revealed his disgust at the fact that John Ford, who worked on The Birth of a Nation, was one of the film’s Klan riders. Ford appears, uncredited, as a rider who lifts his hood to see clearly. Subsequently as a director, Ford became famous for his ride-to-the-rescue scenes, particularly in his cavalry films. Quentin Tarantino, “Tarantino ‘Unchained’ Part 1: ‘Django’ Trilogy?” interview by Henry Louis Gates Jr., http://www.theroot.com/tarantino-unchained-part-1-django-trilogy-1790894626. ↵

- “Racist Dog,” Key and Peele, season 2, episode 2, October 3, 2012, www.cc.com/video-clips/djbfk9/key-and-peele-racist-dog. ↵

- However, this should not obscure real-life political facts such as the disturbing presence of Steve Bannon as chief strategist in the Trump White House. Before joining the Trump team, Bannon headed the alt-right (i.e., white nationalist) Breitbart News web empire. ↵

- There is, though, an effective thought exercise here: When in the future and how could the same narrative be played out in an effective laugh-producing comic form? The sketch premiered in season 5, episode 1, on July 8, 2015. One year earlier, the police killing of unarmed Michael Brown in Fergusson, Missouri, sparked widespread protests and birthed the Black Lives Matter movement. US police average about one hundred killings of unarmed black citizens every year. As those tragedies continue unabated, it is hard to see how they could become the subject of farce. ↵

- “Kanye West Ruins Taylor Swift’s VMA Moment 2009,” September 15, 2009, www.youtube.com/watch?v=z4xWU8o2cvA. Swift is associated with Southern heritage (she moved to Nashville at age fourteen) and her earlier genre, country music. ↵

- Of course this “feud” serves the long-term business interests of both parties by keeping them in the celebrity entertainment news. In February 2016, West released a recording with attendant publicity in which he claimed credit for making Swift famous (patently absurd) and saying he would willingly have sex with her (with the implication that she would like this and she should be complimented by his attention). Swift took the high road, responding in a Video Music Awards show message telling her young women fans to ignore haters and follow their own dreams. ↵

- This continues my interest in ephemeral media, a basic characteristic of our digital new media moment. I address this in Jump Cut essays on fan blogging; for example, Chuck Kleinhans, “There’s a Sucker Born Every Minute. Audiences Blog about Sucker Punch,” www.ejumpcut.org/archive/jc53.2011/ckSuckerPunch/index.html. Here my interest is in the streams of comments that collect in response to blog clips and YouTube items. These threads quickly turn to trolling behaviors but also heavily use comic sarcasm to score political points in arguments. While they “disappear” in the most topical blogging (even more effervescent on Twitter and similar platforms), they are also trace evidence of individuals formerly excluded from this curious corner of the public sphere, now being somewhat empowered to express themselves on issues of the moment or day. ↵

- Gremlinbitch87, “Prissy,” February 18, 2011, www.youtube.com/watch?v=PAV3OfHo4n4, contains TheAdelaidehall comments. Clarence Fisher, “Gone with the Women,” September 6, 2009, www.youtube.com/watch?v=hE7w7KaKbmM, mashes the slap scene in Gone with the Wind with Butterfly McQueen scenes in The Women. ↵

- Davis, an elected official, a county clerk in Kentucky, in defiance of a federal court order, refused to issue marriage licenses to gay couples. She became a celebrity hero to the Evangelical Right. ↵