4 Defining National Identity

The Birth of a Nation from America to South Africa

Peter Davis

South African film historian Thelma Gutsche wrote in the 1940s that The Birth of a Nation’s reputation in South Africa “approached that of a fetishism.”[1] Although there must have been many other screenings, the first recorded screening of The Birth of a Nation in South Africa was in 1931; it took place at Johannesburg Town Hall, which suggests some kind of political intent. It was condemned by black intellectual Sol Plaatje, who asked whether the screening was “licensed to fan the embers of race hatred in South Africa.”[2] Why would The Birth of a Nation strike such a chord in South Africa?

The Dutch filmmaker Joris Ivens wrote of Hollywood that it was “the world’s greatest centre of propaganda.”[3] That this propaganda was largely incidental does not make it any less influential. If we take as one aspect of The Birth of a Nation its assertion of white supremacy and black menace, we must not be surprised that this message, through the power of film, was snapped up and emulated in areas where it was deemed important to maintain such supremacy—and this was certainly the case in South Africa. Inextricably linked to these notions of white supremacy, but even more powerful, was the element of nationalism. Expressed in The Birth of a Nation as the welding together of North and South into one union, in South Africa the influence of Griffith’s film can be felt in the rise of Afrikaner nationalism, the final fusion of the disparate factions of the people of mixed Dutch, French, and German descent commonly called Boers (the Dutch word for “farmers”) who ultimately would be known as Afrikaners, or what we might call “white Africans.”

It is unfortunately common to human experience that nationhood is achieved through triumph over adversity, usually after much suffering, and frequently after massive bloodshed. This was certainly the case of the Afrikaner volk, who fought indigenous peoples and finally the British Empire in the attempt to carve out a living space in Africa. At the time of the dissemination of The Birth of a Nation in 1915–1916, Afrikaner unity had not been achieved; there is a strong case to be made that Griffith’s film played an of-necessity indefinable role in winning that goal. An early one-reeler by Griffith, The Zulu’s Heart (1908), shows an awareness in the director of the existence in South Africa of a parallel history with the United States. Primitive in every way, including Zulus played by whites in blackface, The Zulu’s Heart depicts a white pioneer family traveling in a covered wagon and attacked by savages. The comparison with the American mythology of the winning of the West by hardy pioneers requisitely attacked by red Indians would have been immediately apparent to an American audience, just as myriad films about the American Wild West would already have been seen by audiences in South Africa.

To appreciate why The Birth of a Nation could have an influence in South Africa, it is important to understand South Africa’s history; comparisons with America in the mid-nineteenth century should be obvious. Beginning with an overview of the social and political situation in South Africa in 1915–1916, it is necessary to consider three ethnic groups:

- Indigenous Africans (Bantu) were the largest ethnic group by far, still mostly rural, but sending labor to the immensely profitable mines of South Africa. This was a workforce drawn from different indigenous groups, speaking different languages, often with ancient animosities, which made it difficult to achieve any kind of unity and hence bargaining power—which, of course, the white mine owners were adamantly opposed to. This labor force was migrant, often spending years away from the homeland, where they had left wives and children. It was a manual labor force that could never aspire to any kind of higher-level of employment, let alone participation in the South African political process.

- Boers, also known as Afrikaners, had been in southern Africa almost as long as whites had been in the American South. In the early years of the twentieth century, they were still mostly small farmers, employing black labor. But with migration to the cities, they increasingly became overseers and equipment operators, forming a level of labor above that of indigenous Africans on the mines. In numbers, the Boers were somewhat larger than the next white group.

- People of British descent and recent British immigrants, often holding British passports, formed the upper echelon of society, the bureaucracy, and much of the middle class. Many had come as skilled workers from the mines of Britain, and from the colonies, where, in this caste system, they were higher than Boer or Bantu, though not of richer Afrikaners.

There were other ethnic groups, but they are less important for the purposes of this study. In one sense, the history of South Africa from the beginning of the twentieth century has involved the search for some kind of balance between these three groups—not (until the end of the century) of equality, but of pacification. These three ethnic groups had all, within the preceding eighty years, been in conflict: British troops against Africans; Boers against Africans; British against Boers. The battles of British against Africans were battles of conquest and subjugation, with the last such taking place in 1906. This was the last uprising before the turmoil that began in the 1950s.

Ironically, the relationship between Briton and Boer was exacerbated by the Boer–Bantu confrontation. The colony of Cape Town, with its long-established white settlement of a largely Afrikaner population, was taken over by the British at the end of the Napoleonic wars and became a vital staging area for British access to India. This seemed to work well until 1834, when slavery was abolished in British possessions. Boers saw this as a devastating blow to their farming economy. Unlike the situation of the American South, the Boers were not powerful enough to challenge the British by revolt, and in fact the urbanized part of the Afrikaans-speaking population was hardly affected. The solution of the farmers—those who depended on black labor—was to move northward out of Cape Province, seeking free land beyond British control. This migration of some twelve thousand Boers, beginning in 1835, is known as the Great Trek.

Unfortunately, the lands they moved into and settled, as with the experience of pioneers in the American West, were not “free.” What followed was a low-level enduring warfare, in which the invaders regularly rustled cattle, and in their movement northward conducted slave raids on the local population, killing parents and seizing children to be raised as slaves. The skirmishes against the native population culminated in the 1838 Battle of Blood River. Presented by earlier white “histories” as the betrayal of an agreement on secession of some land by the Zulus, it should, of course, be rightfully seen as a response by the local populations to an alien and aggressive incursion. But however just the cause of the Zulus, it was not the decisive factor. Interpreted as a “miraculous” God-given victory, a covered-wagon convoy of 450 Voortrekkers defeated an attacking Zulu force of some fifteen thousand to twenty thousand warriors. Whether God had indeed given the Boers the canonry and musketry that were decisive is disputable, but what is not in dispute is that their overwhelming firepower ensured Boer supremacy in the areas they settled and where they established a number of “democratic” republics—the so-called democracy, of course, being limited to the Boers, who legalized slavery under the euphemism of “apprenticeship.”

But these republics had the misfortune to be sitting on some of the world’s most lucrative deposits of diamonds, gold, coal, and other minerals. Although situated in what was now Boer land, these mines were run by a gang of ruthless European entrepreneurs who managed to engineer the military intervention of a not-unwilling Britain to overthrow the Boer republics. On a smaller scale than the Northern conquest of the American South, the ensuing war was nevertheless just as clumsy and brutal, devastating for the Boer civilian population, whose farms were burned and whose women and children were held in concentration camps that were near death traps. This Anglo-Boer War, which ended in 1902 with British victory, managed to leave in its wake the stuff of heroic legend, which would be turned into an ongoing propaganda-as-history that would eventually lead to the creation of a united Afrikaner volk.

After the defeat of the Boers in 1902, their republics were absorbed as provinces into the British colony of South Africa, under a Pax Britannica that guaranteed a kind of peace in a highly stratified and segregated society, white from white as well as white from black. In 1910, South Africa was granted an independent status within the commonwealth. This status would lead to the gradual rise of Afrikaans political power, starting with the founding of the Nationalist Party in 1915, which sought and finally achieved unity among the various groups of Afrikaners. As a result, they assumed power through the voting box in 1948 and subsequently established the apartheid state of South Africa.

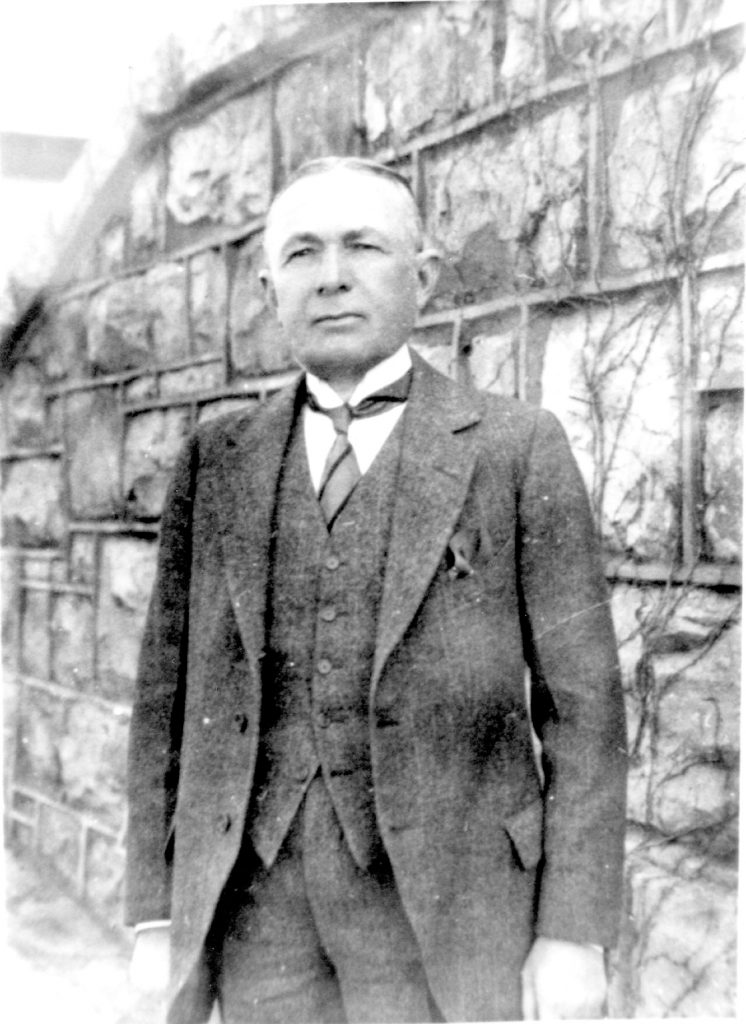

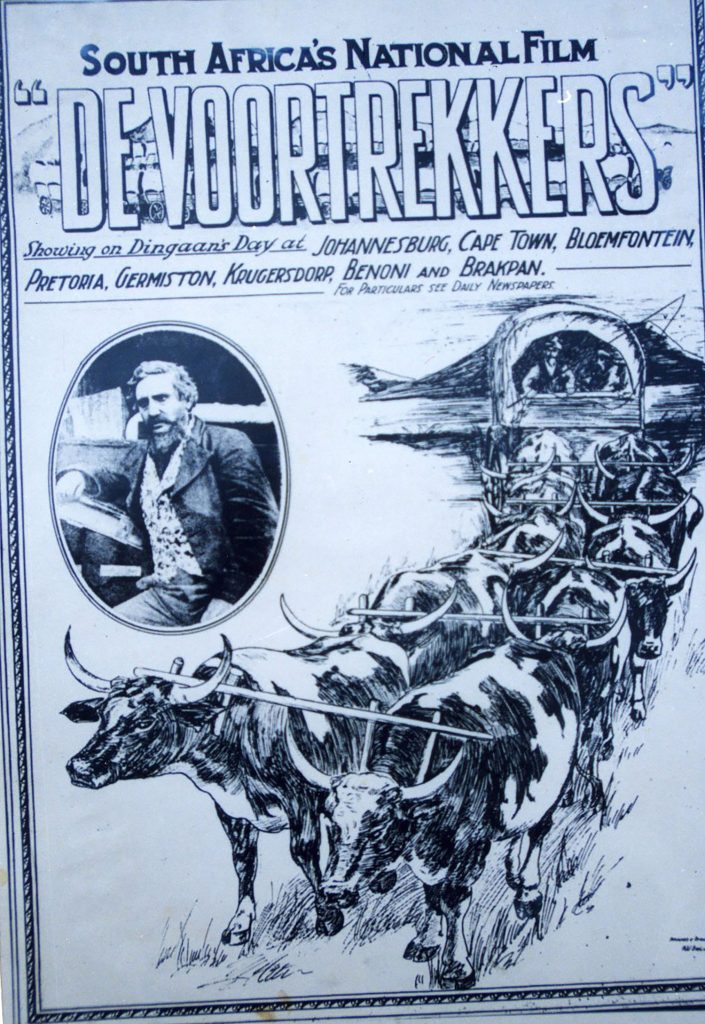

In 1916, South Africa was a society with an immensely rich overclass, elements of which, with the kind of hutzpah that is fired by the entrepreneurial spirit and backed by infusions of cash, in this white population of perhaps a little more than one million people, established a film industry. Prominent was the American-born I. W. Schlesinger, who in 1915 created African Film Productions and threw himself into filmmaking, of which he had no previous experience whatsoever (fig. 4.1). By the time of the making of the first of the two films under discussion, De Voortrekkers, South Africa had a film industry almost 100 percent white in all aspects except African actors and extras and low-level helpers, fed in the beginning by producers, directors, technicians, and actors drawn largely from Britain and the United States. Among the overseas talent Schlesinger imported was director Harold Shaw, another American, who may well have seen The Birth of a Nation before going to South Africa in 1916. It may be of some significance that he was from “an old Kentucky family.” De Voortrekkers would be the most ambitious production hitherto undertaken in South Africa, and it would establish South Africa as a contender—albeit modest—on the world stage.

De Voortrekkers tells the story of the Great Trek up to the Battle of Blood River, as described earlier (fig. 4.2). Intended to celebrate the valor of the Boer invaders, the actual reenactment of the scenes portraying the Zulu warriors involved a massive irony. For the hundreds of extras involved in the staging of the Battle of Blood River—which was shot not at the actual site but just outside Johannesburg, center of the mining industry—African Film Productions approached what seemed to be the most convenient pool of young African men: those in the mines. The irony was that many of these young men were likely descendants of the actual Zulu impis (a group of Zulu warriors) from the last century. As a cautionary measure, the black extras were given spears that would bend, and not penetrate, when used.

The white miners who were acting the roles of the Boer pioneers held no love for the descendants of their former foes, who were also their subordinates on the mines. Some of the white miners allegedly took live ammunition with them into the circle of covered wagons, the laager, to withstand the Zulu onslaught. The result was a battle more lifelike than Shaw had intended:

While the natives were charging the laager, the Europeans within had fired shots. Harold Shaw had shouted to them to stop firing and when they had failed to do so, he had run among the natives in an attempt to stop it . . . when (Police) Major Trew saw a native pull a white man off his horse and jab at him with his improvised assegai, he realized the danger of serious disturbance. So far from co-operating in the dispersal of the natives, the Europeans in laager fired at close range even when the natives were withdrawing. . . . The natives charged the laager furiously; but instead of recoiling and falling “dead”, continued into the laager itself where blows with Europeans were exchanged. Mounted police under the command of Major Trew were forced to intervene and to prevent the natives from attacking the laager in earnest. In moving them away from the scene of the “battle”, the police hustled the natives out of the laager and into the surrounding hills. Some escaped by swimming the river, and one was drowned.

Thus does Thelma Gutsche describe the chaotic situation.[4] With the resentments and desire for vengeance that had been aroused, it seems miraculous that more lives were not lost.

That the film was allowed to proceed to completion means that the authorities thought that there were higher issues at stake. To understand these issues, we have to look at the then contemporary context for this project—not at the implications of battles that had occurred some eighty years before in southern Africa but at battles that were taking place in the second decade of the twentieth century. The imperial power, Britain, was engaged in the most savage and devastating war in its history. This war spilled over into Africa and involved British invasion of Germany’s African territories by South African troops. What was known as the South African Union Defence Force included Boers, many of whom had fought the British sixteen years earlier, and as early as 1914, the first year of the Great War, some of these plotted a rebellion to restore the lost republics. The rebellion was suppressed, but it showed the delicate nature of Boer–British relations at this desperate period of British rule in South Africa, with German forces just over the border in southwest Africa. What possible advantage could there be in making a film that praised the Boer as warrior?

Neil Parsons notes that the historian Gustav Preller had included anti-British material in his draft script but that this was firmly suppressed by director Shaw.[5] The government had full powers of censorship at all times and would not have allowed such scenes. To have stopped production on a film about a heroic episode of Boer history would certainly have had a dangerous backlash from the Boer population. Clearly the government must have seen some advantage in having a film that could be a sop to Boer feelings without arousing anti-British sentiment. In De Voortrekkers, the enemy is not a British army but a Zulu one. In the sense that the Zulus represent the black masses, there is an unstated subtext to the film that it is not the British who are the Boers’ enemy but the blacks—the common enemy for both Brit and Boer in their claim on the land of South Africa. A reviewer in the South African publication Stage and Cinema understood this very well when he wrote, somewhat optimistically, in 1917: “[De Voortrekkers] has probably done more to bring [Afrikaners] and Englishmen together and to help each other to better understanding of the other’s point of view, than anything that has ever previously happened . . . this great picture was produced, to form a lasting and glowing tribute to the heroism and self-sacrifice of the early Boers.” And it was presumably in this portrayal of Boer “heroism and self-sacrifice” that the censors and the authorities, including those responsible for the war effort, saw opportunity. It was seen as potentially raising the martial spirit of young Boers, whose lives would otherwise be devoted to a humdrum existence on the farm or on the mines. This was the same spirit of adventure, the search for glory, that drew millions in Europe to volunteer for the terrible bloodbath that was World War I. The film was wildly successful, and young Afrikaners did volunteer by the thousands to defend the imperial power that had humiliated their people only a decade and a half earlier. At the time, the film was well received even by white audiences. A writer in Stage and Cinema wrote, on December 23, 1916, “I have seen Birth of a Nation, and De Voortrekkers is a greater film.”[6]

Despite the subject, only one Afrikaner is recorded as having worked on the film. This was Preller, who is credited with the scenario. Preller’s self-imposed mission in life was to participate in the creation of a united Afrikaner people. The great schism, which dated back at least to the time of the Great Trek, was the divide between those content to be ruled by Britain and those who sought independence. Preller’s work, including his contribution to the film, would aid in ultimately achieving the aim of unification.

Both De Voortrekkers and The Birth of a Nation use sexual union in a church at the end of the film (in De Voortrekkers, a new baby; in The Birth of a Nation, the newly married couples) to symbolize and sanctify, in the first case, the creation of an Afrikaner nation and in the latter, a united America—both God-blessed and both, needless to say, without black participation.

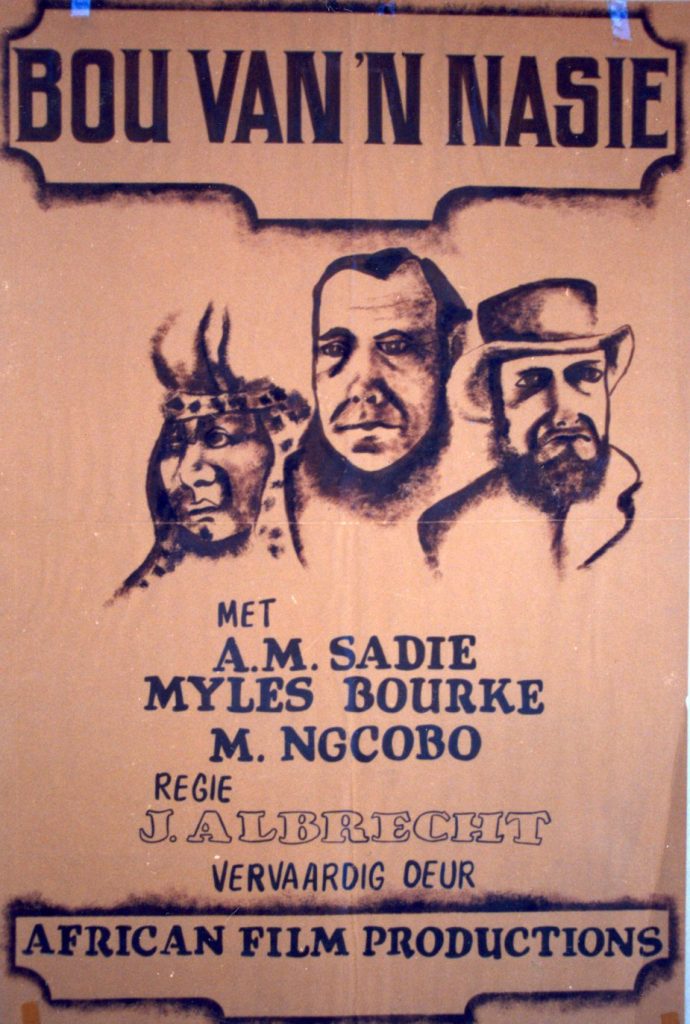

A little over twenty years after the premiere of De Voortrekkers would come Die Bou van ‘n Nasie—and the English title, Building a Nation, immediately invites comparison with The Birth of a Nation (fig. 4.3).[7] This film (now, of course, a sound film), also made by Schlesinger’s studio, was far more ambitious than De Voortrekkers in that it sets out to depict not just one episode but the history of the Afrikaner people from their first arrival in South Africa at the beginning of the seventeenth century up to the establishment of a united South Africa in 1910, after the ending of the Anglo-Boer War in 1902. Its ambition was epic. Its agenda was actively propagandistic.

The title The Birth of a Nation is reasonably interpreted to mean the birth of a united states of America, where Northern whites and Southern whites have been reconciled but where blacks have been suppressed and have no political role. Similarly, Building a Nation purports to project a reconciliation between Afrikaner and Anglo, in which Afrikaners have finally achieved their rightful place. Again, blacks feature only as servants and enemies. Going back to the earliest years of white settlement, Building a Nation creates an idyllic portrayal of Boer South Africa very much like the South portrayed in The Birth of a Nation: a courtly society of genteel people living in an orderly earthly paradise. Differing from De Voortrekkers, where slavery is never mentioned, Building a Nation presents a somewhat labored discussion of that institution, which presents this specious argument from a slave owner: “[Slaves] depend on me as I depend on them.” There is also this well-worn assertion: “These slaves were not unhappy. In the main, they were a cheerful and well-fed band of workers, devoted to their master, and their happy nature found expression in music and song.” And to prove the latter, we are subjected to dance scenes exactly comparable to those in The Birth of a Nation.

African leaders are presented as tyrants with the unfortunate habit of spitting. The relationship of the Zulus with the white race is depicted as treachery and aggression. In a perversion of history, the prime motive behind the Great Trek is offered as unprovoked attack by savage Africans, not the British abolition of slavery. In the film, it is expressed as “the [British] government has failed [to give security],” so “[we must] free ourselves from the oppression of an unsympathetic government, and from the odium cast upon us by philanthropists”—the latter meaning the antislavery movement. Slavery is not mentioned in this apparently dispassionate argument, but one of the guiding principles is to “preserve proper relations between master and servant.” For these reasons, the Boers set out to establish an “independent community with freedom, justice, and peace for all.” Omitted is “providing it is white.”

The making of Building a Nation was synchronized with a reenactment of the Great Trek around the centenary of that event, with ox wagons starting out from Cape Town to make the eight hundred-mile journey to the nation’s capital, Pretoria. The appeal of the centenary of the Great Trek to “those Afrikaner hearts which do not yet beat together” was a clarion call for Afrikaner unity, and it was this aim that Building a Nation supported.[8] The film was the fruit of the new Afrikaans-language film industry, which dated from the early 1930s—that is, the commencement of the era of the talkies—and was itself conceived out of the Afrikaner nationalist movement.

Building a Nation includes the requisite triumph over adversity, after substantial letting of blood. In this longer history, this was the defeat of the Zulus at Blood River and other battles and, most provocatively, the war against British imperialism. Two versions of the film were made. The Afrikaans version premiered to a rapturous audience made up only of Afrikaners on May 29, 1939—too late for the December 16, 1938, centenary of the Blood River victory. (The earlier De Voortrekkers had been shown on that date.) The Afrikaans newspaper Die Vaderland celebrated the film’s propaganda value, deeming it “a mighty factor in our nation-building.”[9] The English-language version was not released for another six months. When it did, the South African Sunday Times baldly stated that it portrayed England as “the villain of the piece,” and it enraged English-speaking audiences.[10] This was also the year, 1939, of the second great threat to British power of the twentieth century.

While there is a symbolic, and somewhat perfunctory, handshake between Brits and Boers at the depiction of the 1910 Act of Union, which gave South Africa independence, British South Africans felt that the British role in the building of white South Africa had been grossly neglected. Funding for the film had come from the government, and the English-language press was especially incensed that public money had gone into the making of a film that was blatantly propagandistic in tone. That the nationalistic aspirations of the film had been achieved was evidenced when Afrikaner audiences booed the on-screen Cecil Rhodes and British soldiers, both hated by Afrikaners. Just as in World War I, there were elements in Afrikaner society, many of them strongly influenced by Nazi Germany, ready to take advantage of Britain’s peril by another rebellion that had to be suppressed. With the outbreak of war against Germany—South Africa once more siding with Britain—there were protests in Parliament against the film, and it was withdrawn from exhibition. Ten years later, after the war, the film would be reinstated, the Afrikaners’ United Party would be voted into power, and it would dominate South African politics up to the end of apartheid. The structure of this new South Africa is foreshadowed in the final scene of Building a Nation: a white farmer guides the plow, his wife sows the seeds, a black leads the oxen. The “savage people” of the early text have been tamed to serve the whites, and there is nary an Anglo in sight.

So both films, I believe demonstrably, played an important role in South African politics. Whereas Building a Nation subtly tuned the lingering, and justified, resentment of the British, De Voortrekkers hides that adversarial relationship to dwell on the swart gevaar, fear of the blacks. In both films, blacks are the more substantial enemy. Yet by the time De Voortrekkers was made, and for the rest of the century, South Africa’s indigenous population did not pose a real military threat. The overriding threat was economic. If blacks were ever to attain equal status in the workplace with whites, the Boers, with their long history as poor whites fully equal to that stratum of the American South, would be overwhelmed. This was the real terror behind the Afrikaner nationalist movement. Yet the economic element does not appear in Building a Nation; it would not have been a factor in the historical period of De Voortrekkers.

What all three films—The Birth of a Nation, De Voortrekkers, and Building a Nation—have in common is an expression of political power. The two ethnic groups—America’s Southerners and South Africa’s Boers—enjoy, then lose, power over another group. In the case of the Confederacy, it is slaves; in the case of the Boers, it is kaffirs, or black Africans. This lost hegemony was essential to their self-definition, their self-respect, and their economy. In all three films, they regain power by (in the American film) terrorizing freed slaves and, in the two South African films, by defeating African enemies. Historically, the struggle for power was much more complex—dare one say, less black and white; in all the films, the politics are simplified by scapegoating blacks. Although the vindictiveness toward the ex-slaves in The Birth of a Nation is quite absent from the South African films.

I began by mentioning Griffith’s film The Zulu’s Heart. The Zulu chief plays a dual role: first as an aggressor who leads the attack on the pioneer wagon; then, with a change of heart, he becomes the protector of the white woman he has widowed and of her child. Thus, succinctly, Griffith lays down the template for depictions of Africans and even African Americans for much of the rest of the century. In one Janus persona, he shows us the Savage Other and the opposite, the Faithful Servant—the Savage Other being those who attack whites and the Faithful Servant those who defend whites. (In The Birth of a Nation, the latter appears as “faithful souls.”)

In both of the South African films, Africans are depicted as treacherous and killers of white women and children as well as being a military threat. However, in the South African films, significantly absent, perhaps surprisingly, is any overt, or even underlying, sexual threat. The notion of Africans as predators of white women plays a significant role in The Birth of a Nation. I offer this as a possible reason for the difference: in the two South African films, the threat to the settlers is overwhelmingly of being defeated in war by enemies of another race, whereas in The Birth of a Nation, the enemy is white, and in that sense presented as on a par with the Southerners. The black slaves cannot reasonably be offered as warrior enemies as the Zulus truly were. Instead, the sexual threat to the purity of the white race has to be manufactured as a fictional enemy more threatening than the real white Northerners—indeed, as a kind of subtle rationale for the war itself. And it is a rational that, in reality, would be used to justify the eternal shame of the lynch mob.

In the Union of South Africa in the first decades of the twentieth century there was no law against interracial marriage, although in the Afrikaner province of the Transvaal such marriages could not be solemnized.[11] Nationally, interracial marriages appeared to be below 1 percent. However, a law that made both intermarriage and sexual relationships criminal offenses was among the first to be passed by the apartheid Nationalist Party government after it came to power in 1949. In early American cinema, the threat of black rape of white women was an explosive subject not lightly invoked. Thomas Cripps mentions only one example—an unnamed film whose description in a catalog included, “the catching, taring [sic] and feathering and burning of a negro for the assault of a white woman.”[12] Notably, the subject was so sensitive that the black villain—as in The Birth of a Nation—was portrayed by a white actor in blackface, creating a grotesque kind of protective barrier for the viewer’s sensitivities.

The “good African,” the faithful servant to whites, although a perennial figure in other South African films as well as featuring prominently in The Birth of a Nation, does not appear in Building a Nation other than in the final scene as a docile farmworker. It is hard to conjecture why. But such a character appears in De Voortrekkers, with surprising effect, because he comes to dominate much of the film, taking over from the white leads, who are largely cyphers.

In the earlier film, we are introduced to the Zulu warrior Sobuza (a nonhistorical character) when he is undergoing conversion to Christianity by missionaries who teach him that killing is wrong. Sobuza’s first test comes when he disobeys the Zulu king Dingaan’s order to kill the king’s baby son, this being a habitual practice of the film’s Zulu king. Sobuza is shamed and driven from the tribe. In his flight, he meets up with a missionary who advises him, somewhat oddly, to “Go South, to the White Man’s country, where you may live without strife.”

Sobuza follows this advice, is accepted by the Voortrekkers, and becomes a servant, but of a particular kind. He cooks for and looks after two young boys, work normally done by women (fig. 4.4). He has become emasculated, in effect, a nanny. However, enough of his warrior manhood is left for him to take on the task of tracking down Dingaan and slaying him in personal combat (This physical participation of the servant in what is effective assistance to the white masters appears also in The Birth of a Nation, as enacted by the “faithful souls”).

So, curiously, once he appears on-screen, Sobuza becomes the central figure. His fidelity is absolute: he becomes the Faithful Servant who defeats the Savage Other. The final few scenes are remarkable. The Boers have built a church dedicated to the Covenant, carrying out their promise to God for preserving “their race and country” in the Battle of Blood River. Inside, they worship, seated in their pews. At the church porch is Sobuza, in Western clothing, staring with ecstasy at the cross. This scene holds a terrible irony, obviously quite oblivious to the filmmakers. Although Sobuza has devoted his life to serving whites, has fought for them and adopted their religion, his skin prevents him from sitting beside them at service—his greatest reward is to listen outside the white church. And this is surely symbolic of the Afrikaners’ positioning of blacks in their society: pacified, servile, dutiful—above all, separate, and never approaching equality. It is a defining image of apartheid.

Peter Davis is President of Villon Films. He is an award-winning writer, producer, and director of more than seventy documentaries, and author of In Darkest Hollywood: Exploring the Jungles of Cinema’s South Africa.

- Thelma Gutsche, The History and Social Significance of Motion Pictures in South Africa, 1895–1940 (Cape Town: Howard Timmins, 1972), 314. ↵

- Edwin Hees, “The Birth of a Nation: Contextualizing De Voortrekkers (1916),” in To Change Reels, ed. Isabel Balseiro and Ntongela Masilela (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2003). ↵

- Joris Ivens, The Camera and I (New York: International, 1969). ↵

- Gutsche, The History and Social Significance of Motion Pictures in South Africa. ↵

- Neil Parsons, “Investigating the Origins of The Rose of Rhodesia, Part 1: African Film Productions,” Screening the Past, July 23, 2009, www.screeningthepast.com/2015/01. ↵

- Jacqueline Maingard, South African National Cinema (London: Routledge, 2007). ↵

- The title They Built a Nation is the literal English translation of the film, but it is also common to see the film referred to as Building a Nation. This chapter privileges the latter translation because Building a Nation is the commonly accepted English denomination. ↵

- Words of Voortrekker leader Sarel Cilliers at the beginning of Great Trek, as quoted by Henning Klopper on the centenary celebrations. ↵

- Thelma Gutsche, “The History and Social Significance of Motion Pictures in South Africa, 1895–1940,” (PhD diss., University of Cape Town, 1946), 348. ↵

- J. Langley Levy, editor of The Sunday Times, strongly criticized the film’s anti-British stance in The Sunday Times, May 26, 1939. ↵

- Hermann Giliomee, The Afrikaners: Biography of a People (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2003). ↵

- Thomas Cripps, Slow Fade to Black (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993), 13. ↵