1 The Birth of a Nation’s Long Century

Cara Caddoo

“Two [officers] that had me by the throat were choking me in such a manner that I couldn’t remember anything,” Aaron William Puller, the minister of the People’s Baptist Church, testified in a Boston municipal court shortly after his arrest. One officer held Puller by the throat and another held him by the back of the neck as they dragged him for at least fifteen city blocks. “I wasn’t conscious of much of anything that was taking place, but I think the officers who had me by the neck and throat let go at Boylston Street,” he explained to the court (fig. 1.1).[1]

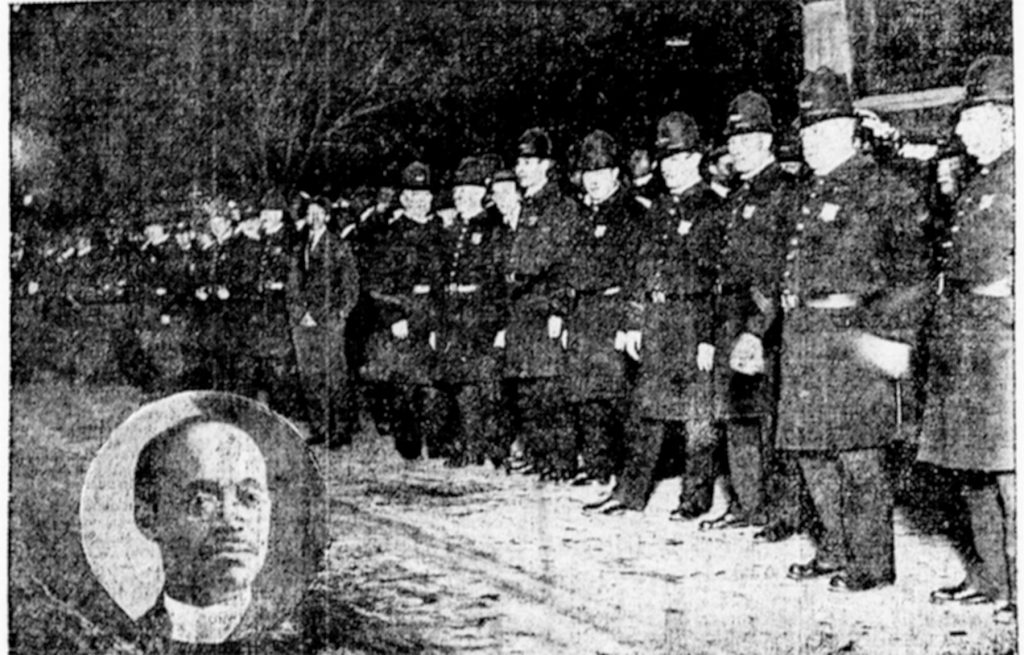

Puller was one of nearly a dozen individuals the Boston police force arrested in the proximity of the Tremont Theater on the evening of April 17, 1915. “Army of Police Nip Theater Riot in Bud,” the Sunday Post exclaimed the next morning, with a photograph of Aaron Puller dwarfed by a larger image of Boston’s police force. The officers stand in a row, shoulder to shoulder, in identical uniforms. Most of those arrested had directly clashed with this “army” of police, including James L. Dunn of West Newton, Massachusetts; Stephen Massey, a driver; James T. Bivens, a railroad porter; a woman named Lugenia Foster; and Clara Foskey, a thirty-year-old black Canadian married to a railroad porter, who was charged with assaulting an officer.[2]

The confrontations between Boston’s police officers and the local black population occurred during the protests against D. W. Griffith’s photoplay The Birth of a Nation. By early March 1915, black Americans had already organized demonstrations against in the film in cities such as Los Angeles and New York. Soon tens of thousands of black protesters, including those in Boston, had joined the broad-based, concerted battle against the film. The campaigns engaged hundreds of organizations and unfolded in more than sixty cities in the United States, the Panama Canal Zone, Hawaii, and Canada. By the end of World War I, the fight against The Birth of a Nation had transformed into the first mass black protest movement of the twentieth century.[3]

What can the protests against The Birth of a Nation teach us today, more than a century later? Since Thomas Cripps’s groundbreaking study Slow Fade to Black, scholars have described the campaigns against the film as a vivid example of black agency and resistance during the nadir of race relations. Historians have acknowledged that the protests helped activists gain experience and build institutions but have wondered whether the efforts were ultimately counterproductive: they did, after all, provide free publicity for Griffith’s film and draw resources away from other causes and from black film production.[4] Interpretations of the success of the campaigns are based on assumptions that they were primarily legal battles, solely interested in film censorship and spearheaded by middle-class organizations such as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (which is given the lion’s share of credit for organizing protests). Curiously little attention is paid to the people on the ground. Yet it was their demands and desires and their long engagement with the motion pictures that made the mass movement possible.

A broad swath of black Americans campaigned against The Birth of a Nation because the movement encompassed many of their most urgent material, cultural, and political concerns. Black communities had early and substantial engagements with moving pictures. Nearly two decades before the debut of Griffith’s film, black Americans had forged their own cinema. Individuals’ interactions with the motion pictures varied, but as a whole, black Americans had invested in the medium as an industry, a communication tool, and a form of leisure. This history fueled the campaigns against The Birth of a Nation, but as protesters interacted with one another—and the white supremacists who defended the film—the mass movement took on new dimensions. In cities such as Philadelphia and Boston, the local campaigns came to emphasize issues of pressing local concern, including police brutality and the role of law enforcement in the protection of private property. As we reflect on the centennial of The Birth of a Nation, the protest movement continues to offer important insights into our historical present.

On the day of Puller’s arrest, the bespectacled fifty-six-year-old minister had arrived at the Tremont Theater shortly after 7:30 p.m. with the intention of purchasing a ticket to D. W. Griffith’s photoplay The Birth of a Nation.[5] Across the city, reports of the film’s exhibition at the Tremont had sent black Bostonians and their supporters into an uproar. Puller, as a “representative of the local colored people,” had petitioned the mayor’s office to block certain objectionable scenes from the film’s exhibition in Boston. He was curious whether the request was carried out, and, hoping to see for himself, he approached the box office and requested a ticket. “There are no tickets to be sold,” the employee of the theater told the minister. “I started to leave the lobby,” Puller explained, “and when nearing the street I stumbled. A policeman gave me a slight shove which hastened me to the sidewalk. Outside were about 25 other colored people, all of the better class. Dr. Thornton, who had a ticket in his possession and who was about to go in with me, was pushed out when I was. While we were standing there in the street along came Dr. Lattimore, another prominent colored man, who said to us ‘They are selling tickets.’”

When a scuffle broke out between a police officer and several protesters, Puller interceded by writing down the badge number of the officer involved in the incident. Without warning, a plainclothes police officer knocked the minister to the ground. In the chaos, Puller recalled Sergeant King directing the officers to “lock that nigger up.” Meanwhile, inside the lobby of the Tremont, a group of protestors gathered to watch W. Monroe Trotter, editor of the anti-accommodationist black newspaper the Guardian, as he attempted to purchase tickets to the show. When ticket booth vendors refused to sell Trotter a ticket, he protested, and a crowd rushed into the theater to his defense. Trotter was then struck in the jaw by a plainclothes police officer and subsequently arrested for “disturbing the peace.”[6]

Skirmishes continued throughout the night between the black public and the police. James L. Dunn of West Newton, Massachusetts, a town about half an hour by train from Boston, was arrested outside the Tremont Theater and charged with using profanity toward an officer. He later testified that he had been swept into the commotion by police officers who were indiscriminately harassing black people in the vicinity of the theater. Dunn explained that he traveled to Boston on Saturday night to shop with four female acquaintances, including his niece Lillian Lawson. After police officers outside the theater demanded he quickly move from the area, Dunn bristled. According to his testimony, he quipped, “My Lord, man, how do you expect for me to move any faster than I am.” The officer, in response, “grabbed him and twisted his wrist, which [was] still sore” more than week later.[7]

Police officers provided conflicting accounts of the events that unfolded on the night of April 17. Despite the inconsistencies between the recollections of the police and the people who were arrested, both sides’ testimonies pointed to the question at the heart of the conflicts: Who protects the rights of black citizens? Black protesters and passersby complained that the patrol officers ignored their rights to public space and fair access to public accommodations while defending the interests of their white counterparts. During the trial, Dunn and his niece depicted Dunn as an upstanding citizen, teetotaler, and a trustee of his Baptist church. They framed his response—“My Lord”—as a bit huffy but far from incendiary. In contrast, two white police officers described Dunn as physically confrontational and verbally abusive. According to Sergeant King and Officer William G. Carnes, Dunn made “gestures” and swore at the officers. “He said he was a citizen and that the ‘cops’ were ‘foreign — — white trash,” King told the court.[8] Had Dunn lodged these insults at Sergeant King, a second-generation Irish American, and the white officers outside the theater, his invectives would have been vehement declarations of Dunn’s claims to his rights as a citizen, even if they pivoted on nativist presumptions.[9] In any case, both versions of the events illuminate the fact that issues such as fair access to public space were equally as, if not more, important to the protests than just the content of Griffith’s motion picture.

In essence, at the same time protesters participated in the broader transnational movement, they were mobilizing around issues of pressing local concern. Such interactions raised issues that, at first glance, might seem far removed from the campaigns against Griffith’s film. In Boston, police violence remained at the forefront of the demonstrations against The Birth of a Nation. When more than one hundred people showed up to testify in defense of the protesters during a special session of the municipal court, many specifically focused on the actions of the police. Witnesses testified that officers had indiscriminately targeted the black populace while ignoring the illegal actions of the white theater management. When Mary E. Moore of 36 Warwick Street, Roxbury, took the stand, she testified that the box office had sold white patrons tickets before and after her but refused to sell to her. When she asked Sergeant Martin King why William Monroe Trotter was arrested, King told her to “shut up.” Others testified that they had witnessed or personally sustained injuries from the police.

Violent encounters between black protesters and police officers also marked the Philadelphia campaign against The Birth of a Nation. On September 21, 1915, shortly before 10:00 p.m., a brick crashed through the glass window above the entrance of Philadelphia’s Forrest Theatre. Instantly, the streets erupted into a “bloody scene” of the “wildest disorder.” Police charged with batons and revolvers. The crowd, which consisted mostly of black demonstrators, scattered. A few dashed for the building’s main entrance. Hundreds more fled up Broad and Walnut Streets, the police at their heels. “Those who could not run fast enough to dodge clubs received them upon their heads.”[10] Two protesters threw milk bottles at the officers pursuing them. At the corner of Walnut and Broad, someone hurled a brick at Officer Wallace Striker. On Juniper Street, either a rioter or a police officer fired shots into the air. By night’s end, more than a score were injured, several arrested, and the theater defaced. Nineteen-year-old Arthur Lunn, a farmer from Worcester County, Maryland, was charged with inciting the riot. Dr. Wesley F. Graham, pastor of Trinity Baptist, sustained “severe injuries.” Lillian Howard, a caterer; William A. Sinclair, the financial secretary of Douglass Hospital; and a thirty-three-year-old laborer named Lee Banks received severe lacerations.[11]

It was no coincidence that these protests occurred at the cinema. By 1915, black institutions, industries, and cultural practices were entwined with the motion pictures. Cinema in the early twentieth century was ubiquitous. Even those black urban dwellers who avoided the theater were confronted daily with its presence: churches hosted film exhibitions as fund-raisers, black newspapers published film reviews, and motion picture houses lined the streets black urbanites walked on their way to work or school. While white American film producers constructed their own cinema—which by World War I had grown into a powerful transnational industry—black Americans produced and exhibited their own films, and black cinema was an essential aspect of black urban leisure in the Jim Crow city.[12]

Neither were the protests against The Birth of a Nation the first time a site of leisure had become a battleground for social and cultural power. In fact, we might consider Philadelphia’s Forrest Theatre a fitting location for the events that unfolded in that city. The Forrest’s namesake was actor Edwin Forrest, the American Shakespearean whose feud with “elitist” performer William Macready sparked the Astor Place Riot in 1849.[13] The riot, as scholars Sean Wilentz and Eric Lott have demonstrated, expressed the growing social and cultural divisions among New York’s laboring and middle classes in the antebellum period.[14] Like the events of 1849, the protests against Griffith’s film emerged from a realm of cultural life entwined in the social and political landscape of a quickly growing arena of mass culture.

News of the protests circulated by word of mouth and through the black press. The oft-quoted W. H. Watkins of the Montgomery Business Men’s League brought news of his experiences in Boston back to Alabama. “I saw this film in Boston,” he explained. “In leaving the theatre after the production I heard a number of men remark, I would like to kill ever negro in the United States.’ As I walked down the street, I hung my head for I felt as if the whole world was down on me.”[15] In turn, news of Watkins’s experiences and campaign in Montgomery was reprinted in black newspapers across the country, including the Indianapolis Freeman. In Chicago, the Defender printed stories of how Watkins linked Griffith’s film to lynchings in Alabama and Georgia.[16]

Black newspapers published news of the protests of The Birth of a Nation as protesters launched new campaigns from the Panama Canal Zone to Halifax, Canada. The protesters learned strategies and tactics from one another as they cited the film’s libelous representations of the race, its ability to incite violence, its showings in racially discriminatory theaters, and the undue political power of its white producers. Through the protests, they staked claim to their rights as citizens. Criticisms of the film pointed to the growth of the Hollywood film industry. As one correspondent for a black newspaper reported, the “moving picture trust, gorged in wealth it has filched from the people through their patronage of its efforts,” had become “strong enough and powerful enough to entrench itself behind special legal barriers.”[17]

The campaigns against The Birth of a Nation not only enabled protesters to link local issues to the larger movement; they also enabled the participation of a broad swath of black Americans with different interests and tactics. The voices of nonelite, working-class blacks were largely absent from middle-class publications such as The Crisis and from legal proceedings against Griffith’s film. Nonetheless, working-class black protesters still participated in the protests, often by targeting discriminatory public accommodations. Despite the efforts of the Tremont’s management to block black patrons from entering the theater on the night of April 17, nearly two hundred black men and women had managed to sneak inside, including a waiter named Charles P. Ray.[18] As the film was exhibited, demonstrators hissed and exploded about twenty “stink pots,” forcing members of the audience to cover their faces from the choking odor. At ten o’clock in the evening, Ray threw a “very ancient” egg at the screen.[19] In Cleveland, protesters, including “a number of city employe[e]s and saloon loafers,” threw stones at a Jim Crow streetcar after police blocked their demonstration in front of the local opera house.[20] In other cases, the battle against The Birth of a Nation was more surreptitious. Bennie Johnson, a former janitor of the Cecil Theater in Mason City, Iowa, for example, was arrested for breaking into the theater’s operating room, stealing the several reels of The Birth of a Nation, and throwing them into the incinerator.[21]

Black women, too, were at the forefront of the protests. With the headline “Colored Women Run Birth of a Nation Out of Philadelphia,” the Chicago Defender lauded the actions of black women who hurled stones at the police-protected Forrest Theatre.[22] When Clara Foskey was accused of assault and battery of a police officer, at least one woman acquaintance and several men came to her aid after she clashed with an Officer Van Lanningham. According to Officer Thomas H. Dowling, Foskey “elbow[ed] her way through the crowd of theater patrons” and attempted to use her “hat-pin” as a weapon. When Van Lanningham ordered her to move away from the theater, Foskey refused. Van Lanningham attempted to “force her to go along”—perhaps by pushing her or stepping on her feet.[23] Foskey reportedly struck Van Lanningham and was placed under arrest. Protestors Stephen Massey, James T. Bivens, and Lugenia Foster ran to help Foskey and were charged with attempting to rescue a prisoner. In other cities, members of elite black women’s organizations, including the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs and local chapters such as the Arizona Colored Women’s Clubs, abstained from engaging in physical altercations. Yet these women registered their discontent with The Birth of a Nation and actively participated in the campaigns by organizing petitions, lectures, and fund-raisers—activities that comfortably fit with their middle-class sensibilities.[24]

Indeed, participation in the campaigns could take many forms. When thousands of blacks and several hundred white allies gathered in front of Boston’s Faneuil Hall after the April 17 Tremont Theater demonstration, tens of thousands of African Americans followed the story in the black press. They learned that the crowds sang “We’ll Hang Tom Di[x]on to a Sour Apple Tree” and that black women passed around hats to collect money for the fines levied against the protestors.[25] Other forms of direct action have likely escaped the historical record because the protesters deliberately disguised their identities or worked clandestinely.

On April 26, 1915, more than a thousand black protesters in Boston adopted a resolution that linked the objectionable film to police brutality and discrimination. The resolution criticized local police who had behaved as agents of the theater managers:

To the Mayor and Police Commissioner of Boston

Whereas, To act as ticket sellers or ticket takers for a theater is not the proper function of a policeman who[se] salaries are paid by public taxation; and,

Whereas, For a policeman to stop a citizen in the entrance lobby of a theater is illegal and for a policeman to demand to see and scrutinize the theater ticket and to check a citizen at the door is a violation of personal liberty.[26]

The final declaration read:

Resolved, That we protest such action by the Boston police at the Tremont Theater during the run of “The Birth of a Nation,” and that we demand a cessation of such invasion of public rights, and that any place which is deemed to make such police action necessary be stopped at once.[27]

The resolution, which directly linked police brutality to the campaign against The Birth of a Nation, articulated both older and new conceptions of black citizenship. Reverend Herbert Johnson told the audience that they could not win “by force” but reminded them of their power as a political constituency. “There are, understand, some 18,000 or 20,000 colored voters,” he explained. “With the political parties as closely divided as they are, you have very nearly a balance of power if you will stand together and support the man, irrespective of color or creed, who stands by you.” Aaron Puller, the minister who was violently arrested by the police during the demonstrations outside the Tremont Theater, counseled “race unity, race agitation and race sacrifice as the weapons available for fighting the issue.” Minister Samuel A. Brown asserted that these rights extended beyond the law. “If no law is made which has teeth in it to stop this infamous thing,” he explained, “I believe that white and colored people of Boston will make such a demonstration as will make unprofitable to exhibit the filth known as ‘The Birth of a Nation.’”[28] “The mayor will not grant us our rights and we propose to take them into our own hands.”[29] It is important to note that this report of the April 26 meeting in Boston was published in the Washington Bee, a black newspaper published by Calvin Chase in Washington, DC.

At the same time, protestors used the language of basic rights to criticize Griffith’s film and to stake claims to self-representation on behalf of the race. In St. Paul, Minnesota, black residents admitted they had only been able to eliminate a few scenes from the film but believed their demonstrations “showed that we do not intend to have our rights utterly ignored or ruthlessly trod upon without protest.”[30] The Chicago Defender was especially vocal on the issue of rights in regard to The Birth of a Nation. In a classic call to action, the paper argued that the film’s mischaracterizations of the race threatened the freedom of black Americans. “Let us always register our protest, often unheeded, against violation of our natural rights, and the despoliation of the privileges of our citizenship,” the paper announced.[31] A correspondent for the Indianapolis Freeman similarly saw Griffith’s film as a strike against the civil rights of black citizens. “‘The Birth of a Nation,’” the writer lamented, “is meant as the Negroes’ civil death.”[32] Framed as a “natural” or “civil” right, these demands for on-screen self-representation helped fuel the simultaneous emergence of a new black film production industry.

The protests against Griffith’s film reveal the many ways that cinema—as a place, a medium, and a set of practices—overlapped with the experiences of black people in the early twentieth century. For the black men and women who protested the film, The Birth of a Nation was more than a projected image. It was part of a fast-growing racially exclusive industry promoted by white supremacists and exhibited, for the most part, in segregated theaters that were protected by the police. John B. Schoeffel, the manager of the Tremont Theater, relied on the Boston police force to protect its private property while it explicitly broke Boston laws. Evoking anxieties about black male criminality, the manager explained that he had learned a “certain gang of colored men” planned to “raid the theatre and destroy the picture and booth.” “In pursuance of this information the management arranged with Supt of Police Michael H Crowley for police protections” because of a fear that the men would be “engaged in the attempt to destroy property” that would cause “serious damage to property,” therefore “police protection was sufficient to keep order as far as we know.” “All through the night, however, a police guard was maintained outside and inside the theatre, to prevent any breaking of windows or an attack on the films.”[33] Within the campaigns were critiques ranging from police harassment and brutality to theater discrimination, economic privilege, state-sanctioned violence, and demands for the right to access public space and leisure venues.[34]

Through the summer of 1915, the protests in Boston continued. They were not as spectacular as the events that had unfolded in April, but they nonetheless demonstrated a sustained movement against Griffith’s photoplay. According to the Boston Daily Globe, a group of sixty protesters, “a majority of them women,” walked in pairs along Tremont Street in front of the theater. Among those arrested were Evelyn B. Washington, age 26, of 77 Sterling Street, Roxbury; James H. Kingsley, 47, of South Trumbull Street, South End; Carl T. Prinn, 22, of Gay Hear[t?] Street, Roxbury; Jacob Johnson, 33, of 42 Hammond Street, Roxbury; Augustus Granville, 45, of 53 Hammond Street, Roxbury; Estelle E. Hill, 36, of 309 Columbus Avenue; Raven W. Jones, 34, of 38 Cunard Street, Roxbury, and Jane W. Posey, 35, of 63 Ruggles Street, Roxbury. “Dr. John B. Hall of 60 Windsor St., Roxbury, furnished bail for the prisoners and they were released.”[35] In Philadelphia, middle-class religious leaders such as Wesley F. Graham, who was beaten by police outside the Forrest Theatre, would continue to criticize police violence. In 1918, after police response to antiblack riots in Philadelphia once again brought these issues to a head, he and other ministers formed the Colored Protective Association.

Recent centennial reflections on The Birth of a Nation have cast the film as a powerful symbol of the past, as evidence of a shameful history of racism that US society has overcome. Yet if we consider the goals, demands, and desires of the men and women who fought against the photoplay, a different lesson comes into view. For the protesters, the significance of The Birth of a Nation extended beyond its text. It was inseparable from a system that privileged the film’s white producers, distributors, theater proprietors, and audiences. For instance, publicly funded institutions such as the police not only refused to protect the rights of black Americans who faced discrimination in theaters where the film screened but also attacked black protesters who asserted their rights to occupy public space during the campaigns.[36] In light of ongoing antiblack police violence, the continued denial of black Americans’ rights to public space, and the systemic valuation of private property over black lives, the history of The Birth of a Nation is just as much a story about our present as it is of our past.

A century after the protests of The Birth of a Nation, on June 27, 2015, a young woman named Bree Newsome climbed a thirty-foot flagpole outside the South Carolina state capitol and removed the Confederate flag. She was promptly arrested. Less than two weeks had passed since a white supremacist murdered nine African Americans at the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in nearby Charleston.

Like the men and women who gathered to protest The Birth of a Nation, Newsome’s act targeted a broader system of racial injustice and antiblack violence. She understood the flag as a symbol of racial hatred, but its significance lay not only in the object itself but also in its location—placed at the steps of the state capitol. “It is important to remember that our struggle doesn’t end when the flag comes down,” she later wrote. “The Confederacy is a southern thing, but white supremacy is not. Our generation has taken up the banner to fight battles many thought were won long ago. We must fight with all vigor now so that our grandchildren aren’t still fighting these battles in another 50 years. Black Lives Matter. This is non-negotiable.”[37]

Cara Caddoo is Assistant Professor of History at Indiana University. She is author of Envisioning Freedom: Cinema and the Building of Modern Black Life.

- “Birth of Nation” Causes Near-Riot: Alleged Plot to Destroy Film, Boston Daily Globe, April 18, 1915, 1; “Roughly Used by Police Negroes Testify in Court,” Boston Journal, May 4, 1915, 4. ↵

- New York Age, September 23, 1915, 1. ↵

- Aspects of this chapter draw from my book Envisioning Freedom (especially chapter 6), and from “The Birth of a Nation, Police Brutality, and Black Protest,” Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era 14, no. 4 (2015): 608–611. ↵

- Thomas Cripps, Slow Fade to Black: The Negro in American Film, 1900–1942 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993), 41–69; Janet Staiger, Interpreting Films: Studies in the Historical Reception of American Cinema (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1992), 139–153; Jane Gaines, Fire and Desire: Mixed-Race Movies in the Silent Era (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001), 219–257; Melvyn Stokes, D. W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007), 129–170. ↵

- A. B. Caldwell, A History of the American Negro, South Carolina Edition (New York: A. B. Caldwell, 1919). ↵

- Ibid. Two men were ejected from the theater that evening for throwing rotten eggs at the screen. Baltimore Sun, April 18, 1915. ↵

- Boston Evening Transcript, April 28, 1915, 2. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Martin H. King, United States Federal Census Year 1920, Boston Ward 17, Suffolk, Massachusetts, roll T625_737, page 7B, enumeration district 446, image 590. ↵

- “Film Play Cause Hurt to Divines,” New York Age, September 23, 1915, 1. ↵

- Ibid.; “Colored Women Run Birth of a Nation Out of Philadelphia,” Chicago Defender, September 25, 1915, 1; Harrisburg Telegraph, September 21, 1915, 3; Trenton Evening Times, September 21, 1915, 7; Cara Caddoo, Envisioning Freedom: Cinema and the Building of Modern Black Life (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2014). ↵

- Philip C. DiMare, Movies in American History: An Encyclopedia (Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2011), 873; Ellis Paxson Oberholtzer, The Morals of the Movie (Philadelphia: Penn Publishing, 1922), 13. ↵

- Lawrence Levine, Highbrow/Lowbrow: The Emergence of Cultural Hierarchy in America (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1990). ↵

- Sean Wilentz, Chants Democratic: New York City and the Rise of the American Working Class, 1788–1850 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1984), 359; Eric Lott, Love and Theft: Blackface Minstrelsy and the American Working Class (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993), 66–67. ↵

- “Birth of a Nation Brings Out Protest to City Commission. Dr. W. M. Watkins Says Famous Film Has Been Misnamed,” Montgomery Advertiser, February 2, 1916, 12. ↵

- “Birth of a Nation Opposed,” Chicago Defender, February 12, 1916, 1. ↵

- “Birth of a Nation Run Out of Philadelphia,” Chicago Defender, September 25, 1915, 1. ↵

- New York Times, April 18, 1915, 15; Indianapolis Freeman, May 8, 1915, 6; Boston Sunday Globe, April 18, 1915, 3. ↵

- According to census records, Charles P. Ray lived with his mother and appears to have struggled financially. Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, Fourteenth Census of the United States: 1920—Population (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1920); Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, Fifteenth Census of the United States: 1930—Population (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1930), http://www.ancestrylibrary.com; Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, Thirteenth Census of the United States: 1910—Population (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1913), http://www.ancestrylibrary.com; “Say Box Office Discriminated: Two Witnesses Heard in Negroes’ Behalf,” Boston Daily Globe, May 1, 1915, 8. ↵

- Caddoo, Envisioning Freedom, 160; Moving Picture World, April 28, 1917, 658; Cleveland Gazette, April 14, 1917, 1; Cleveland Gazette, January 9, 1915, 3; Cleveland Gazette, August 17, 1918, 3. ↵

- Moving Picture World, December 25, 1915, 2408; Chicago Defender, December 18, 1915, 7. ↵

- “Colored Women Run Birth of a Nation Out of Philadelphia,” Chicago Defender, September 25, 1915, 1. ↵

- Boston Globe, April 18, 1915, 1. ↵

- “Mrs. White Presides,” Chicago Defender, April 15, 1916, 6. Like other black organizations, the Colored Women’s Clubs joined other local civic and religious organizations—including the Christian Methodist Episcopal Church, the African Methodist Episcopal Church, the Baptist Church, and the Colored Men’s Protective League—to fight the film. In Baltimore, over a thousand people gathered at the Bethel Church in Druid Hill at the tenth annual session of the Federation of Women’s Clubs to listen to Ruth Bennett, president of the Chester, Pennsylvania, branch speak of her organization’s struggle against The Birth of a Nation. “Federation of Women’s Clubs Elects Mrs. Mary Talbert Press,” Chicago Defender, August 19, 1916, 3. ↵

- Savannah Tribune, April 24, 1915, 1. ↵

- “1000 Negroes Hear Speakers Rap Photo-Play,” Washington Bee, May 8, 1915, 6. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- “Film Offends Negroes: ‘Movie’ Based on ‘The Clansman’ Causes Riot in . . . ,” Baltimore Sun, April 18, 1915, 1. ↵

- St. Paul Appeal, October 30, 1915, 3. ↵

- Chicago Defender, June 5, 1915, 8. ↵

- Indianapolis Freeman, May 29, 1915, 4. ↵

- “‘Birth of Nation’ Causes Near-Riot,” 1. ↵

- Caddoo, Envisioning Freedom, 159; Robert Gregg, Sparks from the Anvil of Oppression: Philadelphia’s African Methodists and Southern Migrants, 1890–1940 (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1993), 63. ↵

- “Arrest Eight of Objectors,” Boston Daily Globe, June 8, 1915, 1. ↵

- Caddoo, Envisioning Freedom, 159; Gregg, Sparks from the Anvil, 63. ↵

- Goldie Taylor, “Exclusive: Bree Newsome Speaks for the First Time after Courageous Act of Civil Disobedience,” Blue Nation Review, June 29, 2015, http://archives.bluenationreview.com/exclusive-bree-newsome-speaks-for-the-first-time-after-courageous-act-of-civil-disobedience/. ↵