10 Engineering Different Equations in the Wake of The Birth of a Nation

Blackface and Racial Politics in Bamboozled and Dear White People

Anne-Marie Paquet-Deyris

The Obama years saw the issue of race in the media dissolve into the era of the postracial, when race no longer seemed to be an obstacle to progress. For quite a few critics, such as Roy Kaplan in The Myth of Post-Racial America (2011) and David Leonard and Lisa Guerrero in African Americans on Television: Race-ing for Ratings (2013), however, such color blindness can result in bypassing direct confrontation with the persistent problems linked to race in contemporary US society.[1] Postracialism can thus deny problems that are still pervasive in American culture, making it impossible to resolve them.

In the current context of the treatment of racial stereotypes, D. W. Griffith’s controversial 1915 film The Birth of a Nation still seems to be fully playing its part as a point of reference for present-day filmmakers. Griffith’s blatant use of blackface and rewriting of US history have spurred several notable filmmakers, such as Spike Lee and Justin Simien, to recycle what Michael Rogin calls a “racial masquerade.”[2] By flaunting racial stereotypes, Lee and Simien circumvent the great white narrative and address race directly instead of metaphorically; they also write every single character not outside but within his or her own racial background. Black characters are no longer removed from their own histories; rather, they are shaped, defined, and sometimes destroyed by them.

This chapter addresses the cultural, ideological, and sociopolitical aftereffects still wrought by The Birth of a Nation. I discuss the extent to which Griffith’s controversial masterpiece influenced Lee and Simien to distinctly voice racial concerns and tensions and provide representational spaces on-screen in a provocative and reflective manner. How do the two filmmakers subvert the characteristic dynamic of black/slave/character to white/master/hero to instead embrace a wide variety of black stories, experiences, and perspectives? I explore the way in which, one hundred years after The Birth of a Nation—and somehow because of it—the two movies relocate America’s problems with race to the very heart of the national debate and offer a kind of post-postracial screen model directly confronting racial history.

The Birth of a Nation as a Barometer

The impact of The Birth of a Nation is still so strong that the film’s current reception summons very specific and passionate reactions about the staging of race and inequality today. French second-year students from Paris Ouest University who were studying the film recently were asked to comment on five specific clips and photograms from the film: (1) the opening intertitle about “the first seed of disunion”; (2) the sequence of the masters courting while the slaves are either working in the cotton fields or dancing for the masters in demeaning postures; (3) the sequence of the black representatives at the statehouse during Reconstruction cheering when intermarriage between blacks and whites is legalized; (4) the infamous pursuit into the woods and near-rape of the white Flora by renegade black soldier Gus; and (5) Gus’s lynching by members of the Ku Klux Klan. The only version of the lynching scene in which the burning cross has not been excised is the 1915 uncensored print, as Jane Gaines underlined in her keynote address at the June 2015 conference at University College London whose theme was “a centennial assessment of Griffith’s film.”

The undiminished relevance of The Birth of a Nation’s controversial treatment of black people was obvious in most of the students’ comments. They immediately reacted to mischaracterizations of black people in the film and in the Western world at large. They also made direct connections with the representations of Syrian and African migrants on television. Some of them criticized the way that European television channels covered the brawls between feuding gangs of African migrants in the French Calais “Jungle” in summer 2016 and the way police used tear gas and charged the migrants with dogs in order to dislodge and deport them to Britain.

If the filmic narrative is to them of primary importance, they also focused on the type of representational strategy used by the director, paying close attention to any form of bias. Most of the students readjusted the representation strategy with a mostly critical and corrective retrospective glance, voicing their concern in class, for example, when making a presentation on one of the film’s sequences. They seemed to be instantly alert to the codedness of the representation of blackness and reacted to the use of blackface and its highly visual suggestiveness as a very visible distortion of racial representation—a physical signifier and signal that needs to be deciphered in light of The Birth of a Nation’s distorted discourse on race. Somehow, one hundred years later, exposure to Griffith’s stereotypical portrayal of blacks enables the students to gauge the significance of the messages they receive from contemporary movies and media at large.

Similar to how the media are described in Robert Entman and Andrew Rojecki’s pre-Obama book The Black Image in the White Mind, The Birth of a Nation seems to serve as “a kind of leading indicator, a barometer of cultural change and variability in the arena of race . . . encouraging audiences and media producers alike to become more critically self-aware as they deal with the culture’s racial signals.”[3] The students were also highly critical of the kind of paternalistic attitudes peddled by Griffith and most of the (white) critics who celebrated the movie when it came out. Rupert Hughes’s “Tribute to ‘The Birth of a Nation’” in the original 1915 souvenir program, is characteristic of this type of pervasive paternalistic discourse:

Hardly anybody can be found today who is not glad that slavery was wrenched out of our national life, but it is not well to forget how and why it was defended, and by whom; what it cost to tear it loose, but what suffering and bewilderment were left with the bleeding wounds. The North was not altogether blameless for the existence of slavery, nor was the South altogether blameworthy for it or for its aftermath. “The Birth of a Nation” is a peculiarly human presentation of a vast racial tragedy. There has been some hostility to the picture on account of an alleged injustice to the negroes. I have not felt it; and I am one who cherishes a great affection and a profound admiration for the negro. He is enveloped in one of the most cruel and insoluble riddles of history. . . . “The Birth of a Nation” presents many lovable negroes who win hearty applause from the audiences. It presents also some exceedingly hateful negroes but American history has the same fault and there are bad whites also in this film as well as virtuous.

It is hard to see how such a drama could be composed without the struggle of evil against good. Furthermore, it is to the advantage of the negro of today to know how some of his ancestors misbehaved and why the prejudices in his path have grown there. Surely no friend of his is to be turned into an enemy by this film, and no enemy more deeply embittered. “The Birth of a Nation” is a chronicle of human passion.[4]

Most whites shared the same paternalistic attitude, which partly explains the film’s great commercial success. The “negroes” had been subjected to “a vast racial tragedy” that needed to be corrected, but this could only be achieved by accepting a very specific type of reformatted narrative that was “founded on Thomas Dixon’s Story ‘The Clansman’ [and p]roduced under the personal direction of D. W. Griffith.”[5]

Ninety-nine and eighty-five years later, respectively, filmmakers Spike Lee and Justin Simien actively reshaped this type of discourse on race relations by producing their own. As a direct consequence and in the wake of their film experiments, they also “reshap[e] White audiences’ sensibilities, tastes and ultimately market demand.”[6]

“Show and Tell”: Blackness Visible

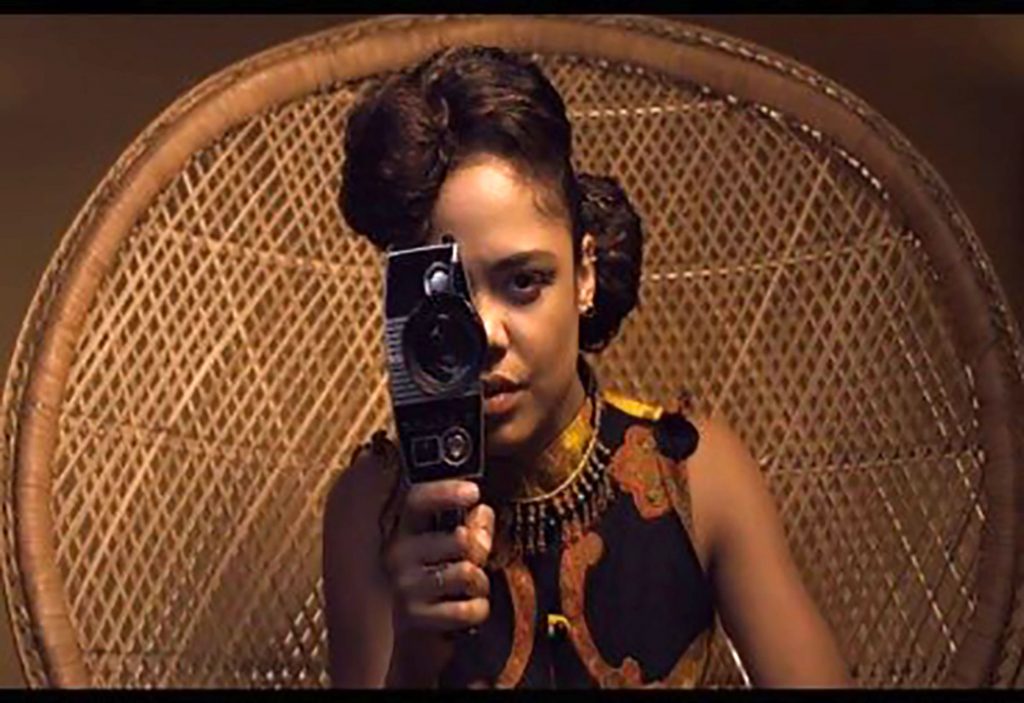

In Simien’s Dear White People (2014), the first intertitle “Show and Tell” announces Sam’s student film project, which is meant to shock. As one of the four main black characters struggling to define themselves in a mostly white Ivy League university, Samantha is framed early on as the most militant; she is a creative cinema student and host of the Dear White People radio show, where she vents her anger at white people. The viewer later learns, however, that she is biracial and has a white father. Sam makes it clear from the start that she identifies as an African American woman speaking and seeing from this specific vantage point. Early medium close-ups frame Sam pointing a camera at the spectator during her controversial radio broadcast or calling out the racial innuendos or outright aggressions experienced by African Americans in their daily lives. The story of the “race war [that went on] at Winchester University” seems to be told and shown from her own perspective in a metafilmic echo of Simien’s (fig. 10.1).

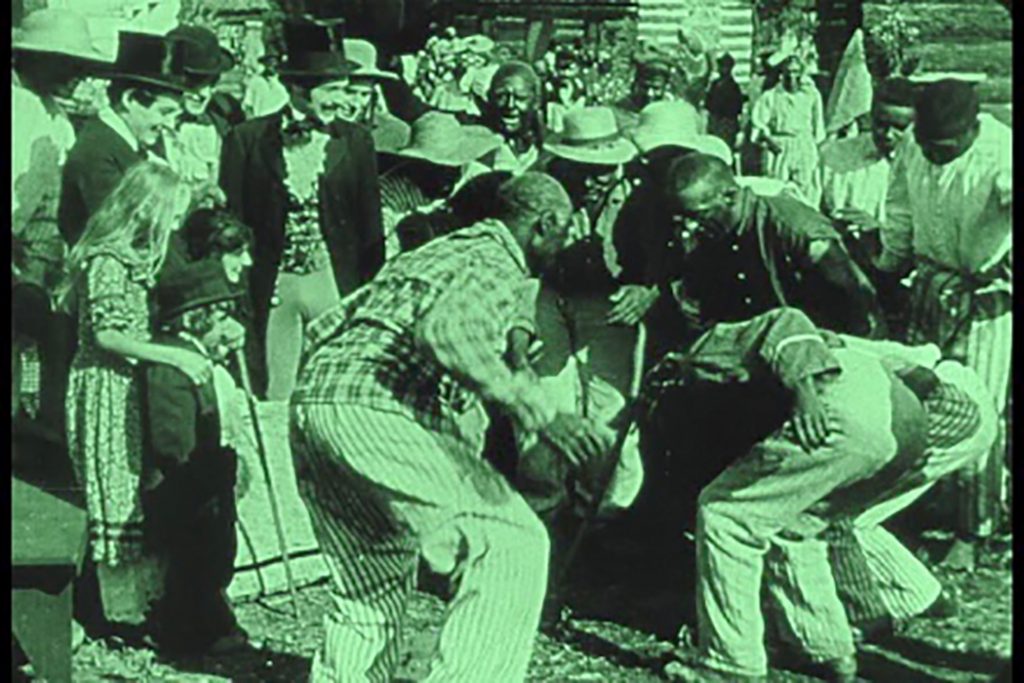

These shots function in inverse proportion to Griffith’s insistence on his own construction of black identity and stereotypes. He forms these constructions explicitly through title cards, as with the quotation from Woodrow Wilson’s A History of the American People about crazed and insolent Negroes, and he refines the loyal stereotype visually with shots of the faithful mammy battling an “insolent and dangerous” black during Reconstruction.

Sam’s critical and ideological stance—to publicly criticize the way white people look at black people and the state of race relations in general—highlights one of the most highly charged questions in twenty-first-century America: What does it mean to be black now, and who can claim “blackness”? Sam’s short film Rebirth of a Nation stages white people in whiteface berating President Obama’s reforms and how his health insurance plan caused havoc.[7] The film literally reimagines the original The Birth of a Nation and testifies to its continuing relevance to recent cultural and political developments. The film within the film first reverses and then displaces the unease black people feel when watching white actors in blackface wearing blackness like a costume that can be disposed of at will. The original intent of blackface minstrels to imitate and portray blacks as intellectually and culturally impoverished is thus turned upside down; white culture is now debased, and white Americans are dehumanized as they are placed in the position of victims of political and racial oppression. Discussing the “Racial Subtexts of Crime News” in The Black Image in the White Mind, Entman and Rojecki note the extent to which “the combined portrayal in front and profile shots yield an impression of guilt based on hundreds or thousands of previous, intertextual memories of the image in news and fiction.”[8] Whiteface functions in Rebirth of a Nation the way blackface was meant to in the days of minstrelsy and in Griffith’s film: the features of the white men and women are accentuated and stereotypical in their outrage, animalistic hatred, and despair at Barack Obama becoming president and at his subsequent health care reform (fig. 10.2).

The way whites are framed recalls Griffith’s staging of malevolent blacks and angry mulattoes in The Birth of a Nation, whether it be Gus, the black “rapist” whose dark, threatening face disappears into the frame and incarnates a diffuse, insidious form of evil, or Silas Lynch and Lydia Brown, portrayed as “vicious” mulattoes. The two mulattoes in blackface are presented as being even more dangerous than blacks. As mixed-race people like Sam in Dear White People, they confuse the racial representational scheme and dream of a new social order. Because they literally cross the racial and social line and cannot be ascribed a specific positioning, they must be punished in a spectacular manner. In the end, Silas, for instance, is manhandled by Ku Klux Klan members so that viewers can only see the back of his head in the lower left-hand corner of the frame before he disappears offscreen.

By toying with these century-old images of blackness, Simien foregrounds what has changed—or not—in the system of representation of blackness. He exposes the constructed notion of race so that contemporary reverberations immediately become obvious and are compounded by the inscription on-screen of some Tea Party members’ racial slurs and attacks on Obama, such as being “not that articulate,” a “Communist! Fascist! Socialist!” who should “go back to Kenya!” (fig. 10.3).

In Paint the White House Black, Michael Jeffries foregrounds the type of metalanguage of race used in the public arena: “A quick Internet search for ‘Tea Party racism’ reveals countless verbal attacks, images and signs about Obama, who is derided as a socialist, terrorist, or Nazi and depicted variously as a topless African witch doctor in tribal garb, Hitler, the Joker, and an ape.”[9]

Simien has Sam briefly play on “the African-male-as-ape overtones of ‘classic’ American films like Birth of a Nation (1915) and King Kong (1933).”[10] Sam unexpectedly substitutes a close-up of a particularly “inarticulate” bulldog, circumventing the more widely used monkey image whose absence ironically becomes all the more noticeable. Furthermore, Simien fully captures the white spectators’ deep sense of unease at such a reversal of the blackface minstrel show conventions: two blond boys can’t even look at the screen; a bewildered brunette slides down in her seat; virtually no one dares to exchange afterward. The white teaching assistant’s negative judgment about the film being “thematically dubious” duplicates what most black people (used to) think of the denigration of blacks in the days of minstrel entertainment. Representing the white male and female in whiteface as alternately hyperviolent and tragic victims plays into the negative stereotyping of blacks as hypersexualized and violent and as being therefore “legitimately” punishable for these very excesses in The Birth of a Nation. Dear White People, and specifically the short Rebirth of a Nation, bring to the fore in an ironically reverse way the “racial skew” and the ethnic offensiveness geared toward blacks.[11]

Exploring the roots of minstrel shows, Kris Collins shows how racial stereotyping stems from “one of white society’s greatest fears, if assessed by its ruthless belittlement of blacks in minstrel entertainment, [which] was the social, intellectual and sexual advancement of African-Am. blacks into traditionally white cultural arenas.”[12] The manipulation of an inverted racial subtext and the recycling of frightening and sensational visual images construct a sense of threat that dissociates blacks from these dangers while associating whites with them. Any distortion of racial representation is hence made ludicrously visible. The fact that we can barely distinguish on-screen that the protesters are white, mostly because they wear hoodies, visually underscores the coded representation of (usually black) rioters that goes all the way back to Griffith and extends up to the present, reverberating in demonstrations such as the ones that followed Trayvon Martin’s shooting by George Zimmerman in a Florida gated community in 2012. The lumping together of these undifferentiated individuals mirrors the media’s overrepresentation of violent crimes and their associations with blacks. It is also intended to make whites ponder the experience of being represented as part of a minority whose members seem to have no distinct identities—like the indiscriminate black crowds in The Birth of a Nation or the members of the Million Hoodie March in Manhattan on March 21, 2012, organized in memory of Trayvon Martin, who was wearing a hood at the time of his death.[13]

Similar to Spike Lee’s approach in Bamboozled, Simien is intent on undoing the media constructs to which we are exposed and the way in which we—involuntarily or not—recycle them. In a British Film Institute interview entitled “Dear White People: ‘All We Had during Awards Season Were Tragic Depictions of the Black Experience,’” Simien comments on the choice of comedy as a useful film genre and makes sure, just as in his opening sequence, that the audience picks up on the satiric intent of his film. The use of slow motion and silent era–like intertitles underlines the way in which comedy leads to a revision of the kind of messages we receive, are conditioned by, and eventually send back out:

You tackle so many controversial subjects. Why did it make sense to you to make it a comedy?

It’s not a straightforward comedy, it has its dramatic moments, but I was just so taken by things like Do the Right Thing (1989), even movies like Network (1976) and Election (1999), that touch upon really deep, heavy subject matters but do it in a way that lulls you into being entertained. Satire has so much power because it gets you to laugh first before you realize you’re laughing at yourself. . . .

Did you make Sam a filmmaker as a way of critiquing Hollywood?

All the characters have some form of self-expression; Lionel writes for the newspaper, Troy is a public figure on campus, Coco has her YouTube blog. I think the movie is saying something, not only about the cultural messages that we receive about ourselves, but the kind of the messages that we then put back out into the culture because of how we’ve been conditioned. I got a lot of personal nerdiness out through her voice but I think of her as an observer. She’s the kind of person who really takes the world in and attempts to blow that up.[14]

In addition to using comedy to radically circumvent the usual tragic mode used to focus on “the black experience”—in the singular and not the plural—Simien foregrounds the extent to which laughter offers a much wider representational spectrum. He also reinscribes himself in a line of directors using bitter irony as a—literally—spectacular weapon, reshuffling the Hollywood Shuffle model, after Robert Townsend’s 1987 satiric film about African American actors in Hollywood. Unlike Townsend’s hero, Bobby Taylor, who is limited to stereotypical black roles because of his ethnicity and competes for them even though he dreams of being able to get any part, Sam tries to resolve the problem of warring racial identities and painful social divisions for herself as a mixed-race person and for others by using race as a trump card. Her discourse on race curiously harks back, however, to Malcolm X’s speech on the “Difference between Separation and Segregation” at Michigan State University in January 1963: “We don’t go for segregation. We go for separation. Separation is when you have your own. You control your own economy; you control your own politics; you control your own society; you control your own everything. You have yours and you control yours; we have ours and we control ours.”[15]

More than fifty years later, Sam still sounds like a Black Power activist. The camera ironically focuses on the survival guide of African Americans on an elite, mostly white campus she plays with while broadcasting Dear White People and later frames her throwing out any white student who ventures into Armstrong-Parker House, the traditionally black residence hall. Simien goes further in his demonstration of how radical identity and racial discourse are constructed than, for instance, Mad Men’s showrunner Matthew Weiner. The latter stages racism and sexual politics in a self-reflective mode. He plays with the white viewers’ (mostly Don’s and Pete’s) relative malaise as they watch Roger Sterling’s infamous blackface serenade to his fair young wife in season 3, episode 3, “My Old Kentucky Home.” As Kent Ono remarks, “the show’s embrace of the past is not only loving but also uncomfortable.”[16] Weiner uses the more conventional inscription of blackface on-screen to “classicly” capture a white man whose face and hands are painted black. And Valerie Palmer-Mehta notes that Roger’s song about “gay” “negroes” in summertime “underscores how this [late 1950s] example of minstrelsy rationalizes racial oppression and dehumanizes its victims” while attempting to emphasize for contemporary audiences how much the notion of political correctness has evolved since the 1950s.[17] Such a moment of self-conscious racial representation problematizes and literalizes one of the main critiques leveled at the show: “Mad Men reports the past from the perspective of white people, as well as through the lens and bodies of white people through how we view unfolding events. . . . The show’s strategies of whiteness, which invariably center on white perspectives, also structure overall attitudes about race, including the way people of color are understood.”[18]

The show’s resonance, then, is not as extensive as Dear White People’s Rebirth of a Nation precisely because the perspective is a white one as opposed to a black one. In Simien and Sam’s films, the black perspective is ironically mediated through the vantage point of yet another young black female wondering in the short Rebirth of a Nation, “What is wrong with these White people?” (fig. 10.4).

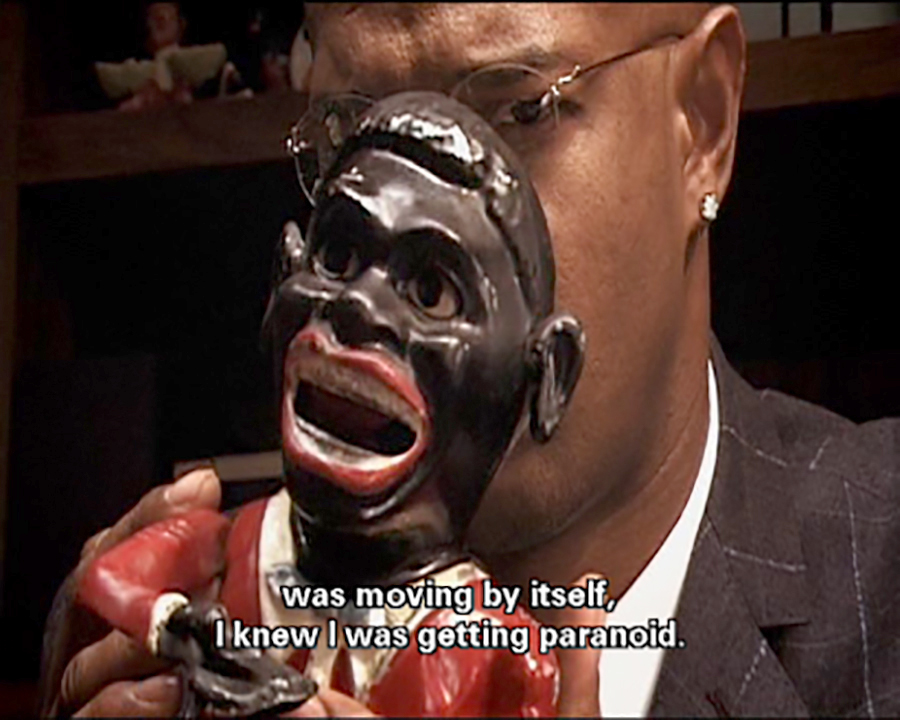

Just as it does in The Birth of a Nation, the white man’s gaze on “the Africanist presence [which] was crucial to [his] sense of Americanness” also functions as the dominant perspective in Spike Lee’s 2000 movie Bamboozled.[19] The black bodies, however, are portrayed in such grotesquely stereotyped ways and blackface is flaunted at the viewer with such vigor that this extreme representational strategy immediately deconstructs the manner in which present-day racism works. By investing the creatively gifted lead black character with authorial control, Lee reinvents the black stereotypes of the Black Buck–turned–Uncle Tom and the dancing coon Donald Bogle first theorized in his 1973 groundbreaking study Toms, Coons, Mulattoes, Mammies, and Bucks.[20] Lee makes them serviceable in a highly satirical fashion in the character Mantan’s Very Black Show (also the French title of Bamboozled), which Mantan is creating for the TV channel he works for. So that the derisive intent of the recycling of such racially offensive stereotypes may not be missed, Lee has the opening sequence coincide with Delacroix’s voice-over giving a definition of satire: the first meaning is “a literary work in which human vice or folly is ridiculed or attacked scornfully,” and the second meaning is “irony, derision or caustic wit.” The media-projected images recycled by “Dela” diversely affect people’s perceptions of themselves and others. They acquire a life of their own and eventually escape his authorial strategy, which was originally to wrest control from his white boss and get him to fire him. Their destructive impact is finally materialized on-screen in a very literal way. Lee’s spectacular variation on the old dancing coon stereotype ends up being recycled ad nauseam. Twelve years after the dancing Toms and coons of The Birth of a Nation, Al Jolson had already set a new trend in what Donald Bogle calls the “Blackface fixation”[21] when singing “My Mammy,” “a classic example of the minstrel tradition at its sentimentalized, corrupt best.”[22] Referring more specifically to Paul Sloane’s 1929 film Hearts in Dixie (in Bamboozled, the name Lee gives Dela’s assistant, Sloan Hopkins, may be an ironic reference to Paul Sloane), Bogle asserts that, “In the end, as the first all-Negro musical, Hearts in Dixie pinpointed the problem that was to haunt certain black actors for the next half century: the blackface fixation. Directed by whites in scripts authored by whites, the Negro actor, like the slaves he portrayed, aimed (and still does aim) always to please the master figure.”[23]

Reminiscent of The Birth of a Nation’s representation of white patriarchy and dancing slaves and of Alan Crosland’s 1927 first talkie, The Jazz Singer, Dela’s creations in blackface, Mantan and his friend Sleep N’Eat, gradually invade the entire screen space, paradoxically hailed by enthusiastic audiences, black, white, Latino, and Asian alike (figs. 10.5 and 10.6).

The shots of the raving crowd and of ethnically diverse faces in blackface artificially creates a strange, literally imagined spectatorial community whose common identification seems to be shaped by the same mediated images. The illusion is so powerful that Lee eventually replaces the live black tap dancers with objects that play even more into stereotyped images of black life: black collectibles finally take over his desk, haunt him in Donald Bogle’s words, and destroy his life. The image thus materializes on-screen the way that historical legacies of racism can not only overdetermine one’s identity but also become literally lethal (fig. 10.7).

Griffith’s representation of the invasion of space by African American representatives (most of them white actors in blackface with some black extras) parallels the proliferation of black memorabilia that eventually invisibilizes the inscription of the African American artists and showrunners. Conversely, at the end of Griffith’s film, the frame is purged of the black presence. To borrow from Linda Williams’s keynote address titled “In the Shadow of Birth of a Nation: D. W. Griffith and Blackface Traditions,” presented at the June 2015 conference at University College London, “the almost magical black disappearances” offscreen are matched in Lee’s movie by the equally magical multiplication of the black figurines in the frame.

Bursting the Postracial Bubble?

Griffith first frames blacks as slow-witted, lazy figures or loyal house servants that would remain nonthreatening and subservient to whites and could therefore be regarded with paternal fondness. He then captures as sex-craved, aggressive, and ambitious beings that were to launch the new elaborate stereotype of the “brute Negroes” [24] of Reconstruction. Out of these set characters, Griffith mostly focused on the figure of the “rapist” in blackface to support the patriarchal cult of the pure, true, white woman. Conversely, Lee and Simien portray black people as self-assertive, fiercely independent, and creative. Samantha White in Dear White People and Pierre Delacroix, Sloan Hopkins, and the two tap dancers Manray and Womack in Bamboozled actually impose a new tone on the two filmic narratives. At the same time, they also recycle some black stereotypes—such as the black militant angry young (wo)man eager to please his/her followers—and hence toy with the same stereotypes that television and movies continue to project. As Simien underlines, however, what matters is to further the “conversation” about what many critics deem to be the pernicious myth of postracialism in an America where the intersection of race and class still very much matters. Asked by host Terry Gross on NPR’s Fresh Air about the development of Dear White People’s specific tone, Justin Simien explained:

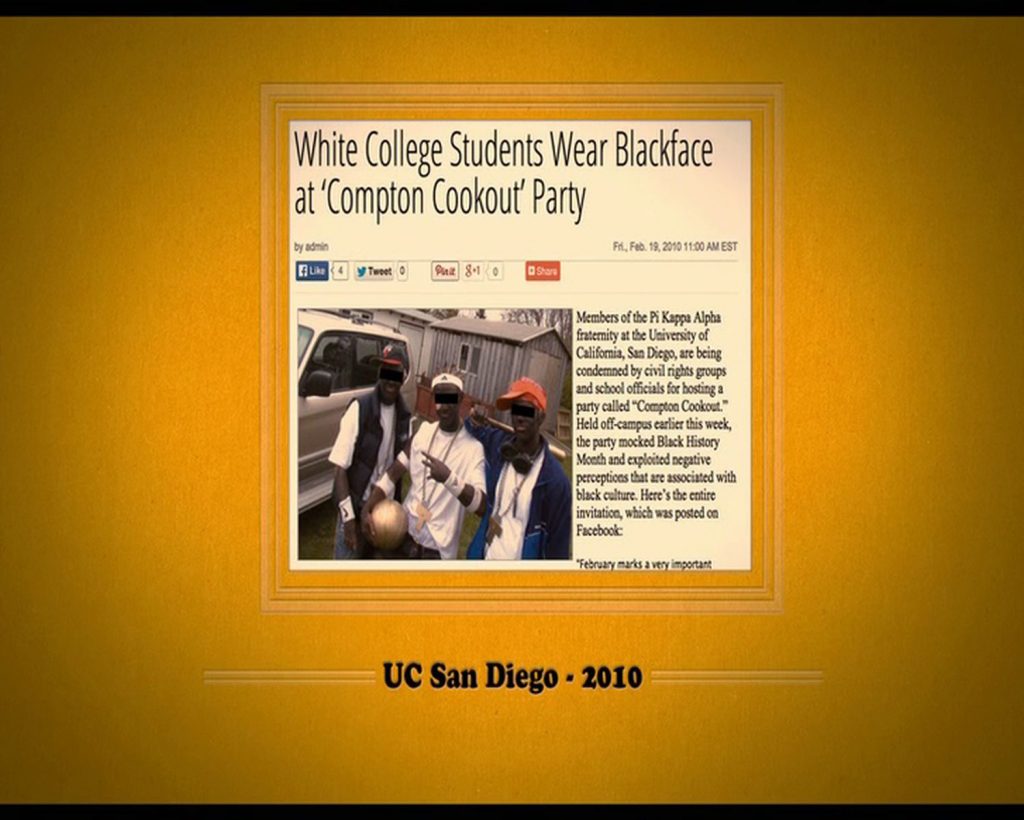

After our first black president . . . everyone thought we were in a post-racial America and then that post-racial bubble [was] burst by the Birther Movement and horrible tragedies like Trayvon Martin, . . . [and] the blackface parties . . . that cumulatively awakened me to just how dangerous covert racism can be and how it’s a lot more comfortable for us to stick our heads in the sand about it. But that did unleash an anger in me. It’s just people’s refusal to see or to at least be open to experiences different than them. . . . That’s when the film took on a much more charged tone to it and became Dear White People.[25]

Lee’s and Simien’s narratives create interesting dissonances with Griffith’s exclusory white national narrative, which boldly charted the possibility of a different America by rectifying the narrative of the Civil War and literally reconstructing Reconstruction. Tracing a line of continuity from The Birth of a Nation to their own narratives, Simien and Lee function in inverse proportion to postracial narratives in a so-called postracial era. In the January 18, 2010, “‘Post-Racial’ Conversation, One Year In” on NPR’s Talk of the Nation, Ralph Eubanks defined postracial first as an American society where race is no longer an impediment to progress and second as a color-blind society where one is first and foremost an American.[26] In Lee’s and Simien’s movies, as in The Birth of a Nation, however, race is very much the great divide planting the seed of disruption that Griffith underscored in his film’s first intertitle. In this sense, the two movies are also reflexive markers in film history, because they actively focus on the ways that racial identities are constructed and contested through engagement with film and media at large.

Unlike many recent films and TV shows (ABC’s Scandal, for instance), race is not a vanished concept that is no longer a societal issue. On the contrary, it is the very centrality of race that allows Simien and Lee to articulate plural post-postracial discourses documenting racial crises (even though Bamboozled is not a post-2008 Obama-era movie). The directors placed black characters in the lead roles not to silence racial tension but to “orient public attention to questions of society and morality”[27]—and, as Ronald Jacobs states in Race, Media and the Crisis of Civil Society, to foreground the way that, “in the modern media age, a crisis becomes a ‘media event.’”[28] It is significant that each crisis in each film is mediated through a number of characters’ viewpoints and broadcast live on TV, the internet, or the radio. Simien, like Lee, captures the various degrees of response to these crises of different African American individuals, focusing in minute detail on their experiences, interpretations, and performances of blackness. Coco Conners, for instance, a sophomore in economics at Winchester University, shapes her own narrative of identity politics on her blog and web videos by advocating assimilation and upward mobility. Her strategy to fit in directly contradicts Sam’s. One opening shot shows Sam watching the news report about the race war triggered by Garmin Club House white students when they organized a blackface “Unleash Your Inner Negro” party for Halloween (fig. 10.8).

The flashback technique Simien uses to chronicle the development of the crisis on campus enhances what Ronald Jacobs calls “important elements for the different narratives of civil society and nation” and the way in which a “crisis produces a particular type of narrative lingering, which emphasizes not only the tragic distance between is and ought but also the possibility of heroic overcoming.”[29] Samantha very much embodies the “distance between is and ought.” She is only one of the multiple (stereo)types held up to critical scrutiny in Dear White People. As a complex illustration of varied types of racial consciousness in the Obama era, Sam is a locus of resistance to white patriarchal culture. Her second student film chronicles the blackface party crisis at Winchester. Called “Black Faces” in some ironic echo of the theme of the party, it no longer references Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation but focuses on the students’ differing versions of a real incident. Duplicating Simien’s strategy, it gives a platform to the plurality of voices at play beyond Sam’s own, as black and female. It reflects the ways that race affects Americans in real places and instantly draws her peers’ critical acclaim. In the final shots however, Sam’s angry ideological stance comes to an abrupt end when she publicly joins hands with her white boyfriend, Gabe, whom she had so far met in secret. The great black/white divide in American society is rendered temporarily irrelevant, the simple gesture dissolving the boundaries of race. This inverted variation on Griffith’s unnatural biracial couple, Silas and Elsie, and visual echo of loving (white only) couples at the end of the film functions as yet another ironic comment on the final title cards in The Birth of a Nation, “Liberty and union” and “City of Peace.”

In Dear White People’s epilogue, the shots of race-themed parties at major universities immediately impose a refiguration of the happy couple and their short-lived inscription of some postracial bliss. Rooted in the long tradition of using irony in African American culture mainly theorized by Henry Louis Gates Jr. in The Signifying Monkey, the visual contrapuntal effect achieved by such a stark contrast functions as “a metaphor for textual revision,”[30] for some new type of script “expos[ing] race not as resolved but as repressed.”[31] The point seems to be that even if it provides an outlet to discuss the current state of race, there is no real resolution. The “distance” Ronald Jacobs refers to has been appreciated differently according to each individual student’s perspective and seems to fit the least controversial version of the term postracialism as defined by Lawrence Bobo in his essay titled “Somewhere between Jim Crow and Post-Racialism.” To Bobo, postracialism signals a merely hopeful trajectory for social trends and change to come.[32] Moreover, it seems that the concept can be apprehended in temporal terms. This moment in identity politics translates as a potentially dangerous place on the way to another state of interpersonal relations. As Tessa Thompson, who plays Samantha White, remarks, “I feel like we’re in a space where we want to feel like we’re post-racial until we’re at a standstill about talking. Until there’s these eruptions like the Trayvon Martin case, like what happened with the [Los Angeles] Clippers”[33] (when team owner Donald Sterling made racial remarks and, as a result, was banned from the NBA in 2014).

The films Bamboozled and Dear White People and their respective moments in interracial history provide specific representational spaces for such a conversation to unfold. It is a conversation that has been continuously developing and has steered away from Griffith’s fantasy and revisionist exploration of racial and sexual politics and social justice in the newly unified white nation at the end of The Birth of a Nation. An additional meaning of “distance” could relate to the way the characters are very much written inside their racial references so that the presence of their black bodies is no longer a mere token erasing blackness, as seems to be the case in many portrayals of blacks in film and on television. In his Sight and Sound article “Black Like Us,” Ashley Clark emphasizes that “Bamboozled and Dear White People are definitely new millennium texts in the way they deal with the production and effects of new media (dissemination of information on the internet plays a key role in both narratives). Yet tonally they hark back to a gaggle of weird, acidly humorous films that posed thorny questions about race in the turbulent aftermath of the Civil Rights movement, and the assassination of Martin Luther King, Malcolm X and Robert Kennedy.”[34] Playing on the notions of mediation and amplification of messages by the new technologies, Lee and Simien aim to generate some form of change.

A wide variety of discourses are being relayed by major African American figures representative of the different sections of the black community, thus working against the normative Hollywood modus operandi and the versions of black identity created by the media. Both filmmakers underscore how the new media record and distort reality and materialize on-screen the camera eye filming the moments of crisis. As Manthia Diawara puts it in “The New Blackface,” they manage “to stereotype the stereotype,” enabling the performers and creators to “fill all the spaces that the old stereotype occupied and to be the star of the new show” (fig. 10.9).[35]

In Dear White People, the final shot of Sam’s second short film frames her looking straight at the camera, challenging us, the spectators, to have that valuable discourse on blackness, “to at least ask the questions,” as Simien told Ann Lee in the July 2014 British Film Institute interview.[36] Sam’s defiant look and pause materialize on-screen what Michael Jeffries calls “a gathering place”[37] when referring to Obama’s role in American society.

To paraphrase the title of Denzel Washington’s 2007 film, Sam has turned into a “great debater,” bringing the possibility of such a postracial conversation into the public arena, mirroring Lee’s and Simien’s strategies when they went mainstream. Sam’s suggestive silence at the end functions as the exact opposite of Elsie’s shout for freedom at the end of The Birth of a Nation. Elsie’s predetermined discourse was meant to impose a national identity not so much forged from within as violently imposed on the racial Other. Sam’s script includes diversifying stories and testifies to her mastery of the media.

Anne-Marie Paquet-Deyris is Professor of Film and TV Series Studies and African American Literature at Paris Nanterre University. She is editor with Marie-Hélène Bacqué, Amélie Flamand, and Julien Talpin of The Wire: L’Amérique sur écoute.

- H. Roy Kaplan, The Myth of Post-Racial America: Searching for Equality in the Age of Materialism (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Education, 2011); David J. Leonard and Lisa A. Guerrero, eds., African Americans on Television: Race-ing for Ratings (Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger, 2013). ↵

- Michael Rogin, Blackface, White Noise: Jewish Immigrants in the Hollywood Melting Pot (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996), 121. ↵

- Robert Entman and Andrew Rojecki, The Black Image in the White Mind: Media and Race in America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000), 205. ↵

- Rupert Hughes, “A Tribute to ‘The Birth of a Nation,’” in The Birth of a Nation Original Programme (New York: Epoch Producing, 1915), 9–12, New York Library Digital Collections, digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47da-5b30-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99#. ↵

- The Birth of a Nation Original Programme, 1. ↵

- Entman and Rojecki, The Black Image, 189. ↵

- Sam’s short film within the film (24:33–25:50) also echoes Simien’s own internet tests and adjustments when getting ready for the screenplay and movie. It will eventually evolve into an altogether different short at the end. ↵

- Entman and Rojecki, The Black Image, 82. ↵

- Michael Jeffries, Paint the White House Black: Barack Obama and the Meaning of Race in America (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2013), 32. ↵

- Ibid., 8. ↵

- Entman and Rojecki, The Black Image, 78. ↵

- Kris Collins, “White-Washing the Black-a-Moor: Othello, Negro Minstrelsy and Parodies of Blackness,” Journal of American Culture 19, no. 3 (1996): 94. ↵

- “Shooting of Trayvon Martin,” en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shooting_of_Trayvon_Martin. ↵

- Ann Lee, “Dear White People: ‘All We Had during Awards Season Were Tragic Depictions of the Black Experience,’” British Film Institute, July 14, 2015, www.bfi.org.uk/news-opinion/news-bfi/interviewers/dear-white-people-awards-season-tragic-depictions. ↵

- Malcolm X, “Difference between Separation and Segregation,” speech, Michigan State University, January 1963, ccnmtl.columbia.edu/projects/mmt/mxp/speeches/mxt14.html. ↵

- Kent Ono, “Mad Men’s Postracial Figuration of a Racial Past,” in Mad Men, Mad World: Sex, Politics, Style, and the 1960s, ed. Lauren Goodlad, Lilya Kaganovsky, and Robert Rushing (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2013), 300. ↵

- Valerie Palmer-Mehta, “Men Behaving Badly: Mediocre Masculinity and The Man Show,” Journal of Popular Culture 42, no. 6 (2009): 1061. ↵

- Ono, “Mad Men’s Postracial Figuration,” 315–316. ↵

- Toni Morrison, Playing in the Dark. Whiteness and the Literary Imagination (New York: Vintage Books, 1993), 6. Referring to the Americanness of Huckleberry Finn, Morrison also foregrounds the “interdependence of slavery and freedom, of Huck’s growth and Jim’s serviceability within it” (55). ↵

- Donald Bogle, Toms, Coons, Mulattoes, Mammies, and Bucks: An Interpretive History of Blacks in American Films (New York: Continuum, 1996). ↵

- Ibid., 27. ↵

- Ibid., 26. ↵

- Ibid., 27. ↵

- Ed Guerrero, ed., Framing Blackness: The African American Image in Film (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1993), 15. ↵

- Terry Gross, “‘Dear White People’ Is a Satire Addressed to Everyone,” Fresh Air, NPR, October 16, 2014, https://www.npr.org/2014/10/16/356494289/dear-white-people-is-a-satire-addressed-to-everyone. ↵

- Ralph Eubanks, “‘Post-Racial’ Conversation, One Year In,” Talk of the Nation, NPR, January 18, 2010, www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=122701272. ↵

- Ronald Jacobs, Race, Media and the Crisis of Civil Society: From Watts to Rodney King (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), 9. ↵

- Ibid., 9. ↵

- Ibid., 9. ↵

- Henry Louis Gates Jr., The Signifying Monkey (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988), 88. ↵

- Samantha Menard, “The Myth of Post-Racial Television” (unpublished paper, University of Long Island, 2014), 51. ↵

- Lawrence Bobo, “Somewhere between Jim Crow and Post-Racialism: Reflections on the Racial Divide in America Today,” Daedalus 140, no. 2 (2011): 13. ↵

- Ed Rampell, “‘Post-racial’ Dear White People Comedy Premiering,” Mississippi Link, October 9, 2014, 17. ↵

- Ashley Clark, “Black Like Us,” Sight and Sound 25, no. 8 (August 2015): 35. ↵

- Manthia Diawara, “The New Blackface,” in Blackface, ed. David Levinthal (Santa Fe, NM: Arena Editions, 1999), 15. ↵

- Lee, “Dear White People.” ↵

- Jeffries, Paint the White House Black, 156. ↵