2 Great Moments from The Birth of a Nation

Collecting and Privately Screening Small Gauge Versions

Andy Uhrich

A New York Times article from 1965 titled “Classics on Home Screen” is a reminder, in our saturated home media present, of the comparative rarity of being able to own personal copies of films in the decades before home video. The author, Jacob Deschin, writes, almost amazed, that “Any amateur who owns an 8 mm projector can now put on a movie show of old-time classics on his own screen at home. Yes, even David Wark Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation, the 50th anniversary of which occurred last week. The 12-reel film costs $65 [which is just under $500 today] and takes about three and one-half hours of screen time.”[1]

To contextualize why the release of classic films to the domestic market made the news and to better understand how The Birth of a Nation was exhibited and watched in private settings on film prints before home video, this chapter describes the domestic and nontheatrical distribution and reception of The Birth of a Nation from the late 1930s to the end of the 1970s. By focusing on the nontheatrical market in general and private film collectors in particular, this chapter adds to previous studies on the film’s circulation and versioning by scholars such as Melvyn Stokes, John Cuniberti, and J. B. Kaufman.[2] The chapter surveys the variety of spaces the film was shown in beyond the commercial movie theater, presents a necessarily incomplete list of the multiple versions that were released for the home market on small gauge film formats, discusses one of these derivative versions of The Birth of a Nation in greater detail, and presents the debates collectors engaged in around their various justifications for screening the film (fig. 2.1).

In this discussion, I explore the following questions: What was the role of private individuals in circulating and exhibiting The Birth of a Nation? How did the specifics of nontheatrical exhibition spaces—homes, classrooms, school auditoriums, community spaces, and private screening rooms—and the different textual and material versions of the film—8 mm or 16 mm, sound or silent, black-and-white or color, full-length or excerpted short—alter the experience and context of watching it? How did one subset of American cinephiles address issues of Hollywood’s racism in their canonization and appreciation of cinema as an art form? Building on that last point to widen the scope of this analysis, how have collectors—and by implication archivists, historians, scholars, and viewers—balanced a desire to restore and exhibit films with a responsibility for a greater social good?

The Birth of a Nation and “the Privacy of One’s Home”

To be fair, many of these questions would not have been the driving force for someone who purchased one of the films mentioned in the New York Times piece; presumably their motivation would have been to own an old film. This was not always an easy task. Film prints were hard to come by. What was available was often a poorly copied print or a short depicting only one scene or a condensation of the original. Showing a film required a high degree of technical knowledge in order to operate a film projector or edit and repair prints. And new prints, when they could be found, could cost up to a few hundred dollars per title.

At that time, from the 1930s to the 1970s, the major Hollywood studios had, for the most part, ignored the domestic market. Earlier efforts in the 1910s and 1920s to make the small gauge projector the successful home media follow-up to the phonograph, and thus a platform with which production companies could sell or lease film prints, had failed.[3] Until the adoption of VHS, the home market was essentially ceded to specialized film companies. Distributors such as those mentioned in the New York Times article—Blackhawk Films, Entertainment Films, Griggs Moviedrome—were small enough that they could make a profit from selling films in the public domain, or they were willing to break copyright law by duplicating newer, more popular titles. A few of these companies, such as Blackhawk Films, which was one of the largest distributors of commercially produced films for the home from the 1950s through the 1970s, were respectable businesses with several employees and a large and well-cultivated library of films for sale. Some, like Griggs Moviedrome, were collectors who ran films out of their homes and were primarily motivated by a love of cinema, and while they might have duplicated or traded films obtained outside of official circuits, they did so from a desire to preserve and share old films. Others exemplified the worst characteristics of media pirates, dealing in bootlegs and defrauding their customers.

This uncertain marketplace was one additional reason that the home audience for prepackaged films was limited. The audience for home cinema was, as Deschin described in the Times, primarily “collectors of old films and those serious amateurs who want to improve their techniques through occasional study of the great film achievements of yesterday.”[4] In both cases, there was an element of functionality to buying old films; the former bought them to build a collection, while the latter used them as a resource to lift camera angles, shots, and other cinematic signifiers.[5] The effort and cost it took to acquire film prints usually required additional interests or socializing to justify the expense. Collectors and amateur filmmakers were, then, representative of what Greg Waller describes as the “specialized publics” of nontheatrical film. The fantasy, however skewed, of an undifferentiated audience coming together to see the same film in a movie theater was replaced with a “pragmatically targeted filmmaking.”[6] The films did not attract a mass audience, as was the case with the commercial movie theater, broadcast radio, and television networks, but rather a number of different, interrelated, minor audiences. Sponsored, industrial, and educational films were made to meet a precise need among a necessarily limited number of people looking to buy a tractor, attending a job training session, or learning about chemistry or social studies. Or, in the case of the discussion here, various prints of The Birth of a Nation, a film made for the largest public possible, were circulated by and to select groups of cinephiles and film historians.

Showing how specialized these nontheatrical publics could be, I want to emphasize that when discussing the role of film collectors in circulating The Birth of a Nation, the focus of this chapter is on collectors of European descent and not the important African American collectors and film historians discussed in articles by Leah Kerr in Black Camera and by Jacqueline Stewart in “Discovering Black Film History: Tracing the Tyler, Texas Black Film Collection.”[7] My decision to focus on the relationship of The Birth of a Nation to prominent white film collectors is an effort to begin thinking about the role of whiteness in film fandom and in the creation of what became canonized as the classics of American cinema and about practices of film preservation in the mid-twentieth century.

Along with specialized publics were specialized exhibition sites. Or, as Deschin describes the impetus for screening small gauge versions of film classics, “group entertainment in the privacy of one’s home.”[8] The copies of The Birth of a Nation that are analyzed here played in many places besides the living room, including private cinemas, classrooms, film societies, and repertory theaters. Thus, the word private does not adequately describe the specialized audiences to whom these prints were shown or the atmosphere of the screenings. However, it does suggest the insider nature of many of these screenings, replete with alternative and adjacent exhibition strategies and spectatorial positions to commercial moviegoing. The intent of many of these nontheatrical film programmers, or private individuals showing films in their homes, was not, for the most part, to specifically traffic in offensive images; it was to project films that could not be seen elsewhere due to commercial imperatives, copyright restrictions, or censorship.

For example, in a 1967 letter to members of the new Film Society of the School of Visual Arts, film historian and noted collector William K. Everson stated why he did not want members to promote the screenings to outsiders. He requested that members: “do not spread the word among friends outside of SVA, nor discuss the films openly—particularly at places like the Museum of Modern Art where listening ears are always on the alert for private screenings. Many of the films we show are not legally available, and while there is no specific copyright or other infringement involved in these specific screenings, still it is diplomatic to publicize them as little as possible” (emphasis in the original).[9]

Thus, many of these screenings, by design, escaped, or were ignored by, the public eye. This has a particular resonance for The Birth of a Nation, which was regularly protested against by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People at many of the film’s more prominent screenings. Not that there were never protests against nontheatrical or collector screenings of the film. Yet, due to the secretive nature of these specific film cultures and the technical affordances of small gauge film, such as portability and relative ease of use, The Birth of a Nation was exhibited in contexts outside the more controlled setting of the commercial movie house. This offered nontheatrical film programmers a way to show the film despite possible pushback by civil rights groups. In program notes announcing an upcoming screening of The Birth of a Nation in the late 1950s, Everson assures attendees that if the arranged location at a high school is shut down, “we’ll be going ‘underground’ to a little private theatre in New Jersey, so nobody need to be afraid of making the trek [from New York City] for nothing.”[10] Additional examples of similar screenings are examined later in this chapter.

The availability of small gauge film projection also meant programmers and audiences could present a more complicated stance, if not outright contestation, to the film. Though not indicative of a larger approach to exhibiting The Birth of a Nation, in July 1971, the black theater group Grassroot Experience screened the film as the last part of a weeklong film series on representations of black America on film; Griffith’s film was accompanied by jazz records by John Coltrane and Pharaoh Sanders.[11] Details are scarce in the newspaper report announcing the event, but the pairing of the music of the two jazz greats with Griffith’s film suggests the screening might have been intended as a sort of exorcism of the lasting, pernicious power of The Birth of a Nation or perhaps a clash between icons of black art and white cinema. However it was actually presented, that it was shown at a live venue working to fulfill the “need for black theatre in the community” and to stage plays with characters “that Black people can identify with”[12] reveals a use of the film very different from that of white New York cinephiles.

While the focus of this chapter is on how collectors, cinephiles, and amateur film historians recirculated small gauge versions of The Birth of a Nation, more research is required to chart how the Ku Klux Klan and other white supremacist groups used 16 mm and 8 mm prints of the film. The threat that substandard copies of the film posed as a recruiting tool for the Klan was addressed in a December 1970 op-ed piece by historian and political columnist Garry Wills. After recounting how the expanding list of titles available for home viewing allowed him and his mother-in-law to watch Intolerance ( dir. D. W. Griffith, 1916), he noted the “the greatest of D. W. Griffith’s films [The Birth of a Nation] cannot be bought, or taken out of the local library. And for a very good reason.” Due to the film’s promotion of the Ku Klux Klan, “it could be used in private showings, by the Klan or other bigot groups, to fan race hatred.” However, while Wills supported a ban on the film in private screenings because they could not be monitored, he argued against attempts to stop its exhibition in public theaters. If a very small percentage of white racists might be inspired by the film, most of “any normal audience watching The Birth of a Nation” would be exposed to the country’s past horrors and would be better armed to confront current-day forms of the Klan and white racists.[13] Private screenings were dangerous because they could not be policed by the common sense of the mass audience.

Historical precedents for how the Klan might have screened small gauge editions of The Birth of a Nation are covered in Tom Rice’s White Robes, Silver Screens: Movies and the Making of the Ku Klux Klan. During the 1920s, and after the film’s extended theatrical run, Klan chapters in Ohio, Texas, Illinois, Indiana, and elsewhere began circulating preexisting 35 mm prints of The Birth of a Nation on their own. If, during the late 1910s, Klan members would show up in full garb for screenings of the film put on by mainstream commercial theaters, in the following decade they exhibited it themselves “in smaller theaters—some owned by the Klan—and other kinds of spaces. As the Klan reappropriated the film . . . it pulled, stretched, and deepened the divides occasioned by the film’s initial release.”[14] Though the gauge of film and historical period is different from those covered in this chapter, Rice’s example amplifies the larger argument that access to films and the ability to screen them changes their physical and textual shape, and thus their reception.

Still to be confirmed is whether the greater availability of The Birth of a Nation after its entry into the public domain in 1975 was responsible for its increased use by the Klan, which was then led by a newer generation of white supremacists, including David Duke. More research is needed to determine which formats they acquired and how the transportability of small gauge prints, and later home video, might have allowed them to screen the film in new spaces that 35 mm prints could not reach. However, a spate of Klan-produced screenings of the film demonstrates the importance that The Birth of a Nation continued to hold on the group’s social identity and inflammatory public acts.[15] For example, a San Bernardino chapter hoped to rehabilitate views of moderate whites toward the Klan by forming a local bowling league, opening a bookstore, and, paradoxically due to the film then being over sixty years old, “sponsor showings of the film The Birth of a Nation.”[16] On June 3, 1978, Klan members in Fairview, Kentucky, screened the film “to paying customers . . . at an undisclosed location” when they could not gain a permit to burn crosses.[17] Later that summer, a Klan screening held in a community center in Oxnard, California, was contested by antiracist groups who clashed with police.[18] A 1979 Klan screening in China Grove, North Carolina, was met by a protest that started a simmering dispute between the Klan and antiracist groups that culminated in the Greensboro Massacre later that year.[19]

An Incomplete Survey of Small Gauge and Nontheatrical Versions

To provide a sense of the variety of home and small gauge versions that existed of The Birth of a Nation, and which would have been projected at these types of nontheatrical screenings, this chapter now turns to a discussion of the many copies of the film owned by one collector. David Bradley was a filmmaker who started making amateur movies as a teenager, including Charlton Heston’s first film, 1941’s Peer Gynt. Bradley turned professional with a brief career as a director at MGM releasing one feature, Talk About a Stranger (1952), and later made a number of B pictures and cult films, including Dragstrip Riot (1958) and Madmen of Mandoras (1963, later reissued in 1968 as They Saved Hitler’s Brain). Bradley started collecting films as a teenager in the 1930s and by the time of his death in 1997 had assembled one of the largest private film collections in the United States.

Bradley used index cards to document the date when he bought a film, how much he paid for it, and the venues to which he loaned a film. This record-keeping system allows for an analysis of how his collection grew over time, when certain titles became available on the collector’s market, and, for the purposes of this study, a view of one collector’s role as purchaser and circulator of private copies of The Birth of a Nation. Out of Bradley’s collection of about 3,900 film titles on 16 mm, he had six versions of The Birth of a Nation. The chronological order in which he acquired them is as follows: The first two copies he owned of the film were shorts. One was a three-minute reel of excerpts that he acquired in 1943; the other was a nine-minute condensation with new narration called Great Moments from Birth of a Nation from 1953. The latter will be analyzed in greater detail later in this chapter. In 1955, Bradley was finally able to obtain a complete version of the film when he purchased a twelve-reel black-and-white copy of the feature. In 1969, he acquired another black-and-white full-length print. Bradley purchased three reels of outtakes and trims from The Birth of a Nation in 1972. Finally, in 1975, he bought a color version of the feature.[20]

Unfortunately, Bradley did not record where or from whom he located these prints in his catalog records. Perhaps he omitted the information to protect sources that engaged in illegal film piracy. His copies of The Birth of a Nation appear to be a mix of legitimate reissues approved by the copyright holder, gray-market releases produced by small distributors such as Griggs Moviedrome, and, potentially, bootleg copies, or dupes, produced by film collectors with the assistance of a film lab willing to break copyright. Reconstructing a history of the production origins of Bradley’s prints of The Birth of a Nation involves a mixture of following archaeological clues from the prints themselves and from the advertisements that distributors placed in magazines for the nontheatrical, educational, and collecting markets such as Home Movies, Educational Screen, and Classic Film Collector.

What follows is a chronological account of all the versions of the film intended for nontheatrical or the home markets from before 1980 that were uncovered in the research for this chapter. Undoubtedly there are more, especially considering all the dupes that were made by and privately traded among collectors. Information about the source and specifics on how Bradley or other collectors used their personal copies are given along with the details about the prints of The Birth of a Nation. The intent is to acknowledge the range of companies and individuals that were distributing and exhibiting the film, and the transformations—textual, material, and paratextual—that the film underwent as it traveled the collector and nontheatrical circuits.

In 1937, the F. C. Pictures Corporation was distributing a 35 mm sound print of The Birth of a Nation to the educational market.[21] F. C. was a small distribution company in upstate New York that sold films to school, itinerant exhibitors, and other nontheatrical sites. In 1940, the previous owner of F. C. Pictures, Charles Tarbox, was running another company, Film Classic Exchange, which was circulating a bootlegged copy of The Birth of a Nation that had apparently expurgated the most outrageously racist scenes in the film, such as the attempted rape of the Little Sister by Gus.[22] Later, Film Classic Exchange was selling yet another version of the film on 8 mm to the collectors market.[23]

The same year, the Museum of Modern Art Film Library was distributing The Birth of a Nation “to museums, colleges, and film study groups throughout the country” as one of eight films in its fall series.[24] The film is still available for rental from the Museum’s Circulating Film and Video Library in four different versions on 16 mm.[25]

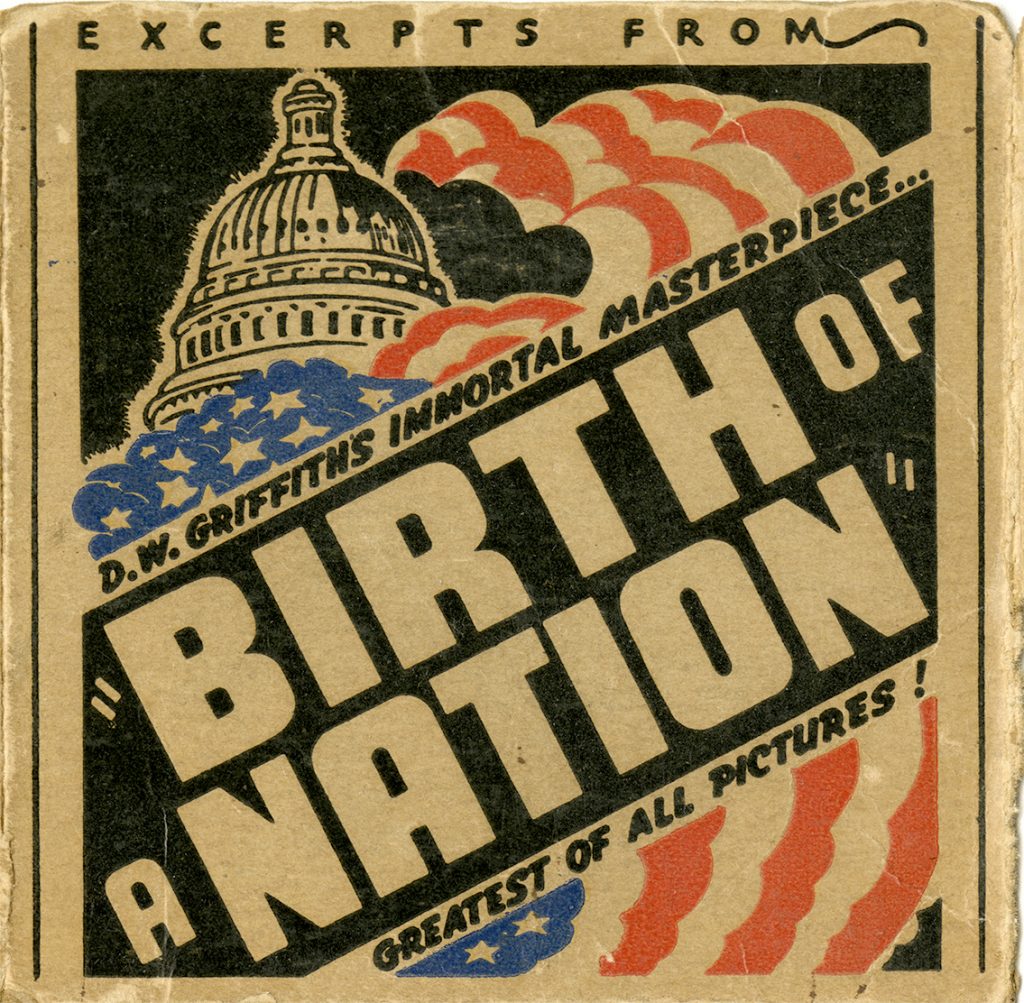

In 1938, the Stone Film Library advertised sound and silent versions on 16 mm to the educational market. An ad in the February issue of Educational Screen reads, “In 1915 TEACHERS AND STUDENTS traveled miles to see it. In 1938 IT COMES TO YOU! THE BIRTH OF A NATION” [capital letters and bold type in the original].[26] The Stone Film Library was started in 1908 by one of the earliest known film collectors, Abram Stone, as one of the first stock footage companies (fig. 2.2).

In the summer of 1942, the Intercontinental Marketing Corp. released two excerpts in either 8 mm or 16 mm: The Assassination of Lincoln and Civil War Battle Scenes. The text of a 1942 ad for these excerpted versions, printed under a patriotic image of the nation’s capitol, which was also the cover of the box they were sold in, reads: “Think of seeing, in your own living room, the mighty battle scenes that have held millions spellbound! Think of unreeling the stirring scenes of American heroism as vast armies charge and retreat—as big cannons roar—as shot and shell rain death and destruction! Think, too, of beholding the great patriotic scenes from American History” (fig. 2.3).[27]

At a moment when the United States had been militarily involved in World War II for just over six months, the distributor of these shorts made a sales pitch based on a patriotic appeal by selecting two scenes from The Birth of a Nation that embodied national sacrifice while still being entertaining. The evidentiary nature of Griffith’s footage as representative of what actually happened in the past is expanded on in the description of The Assassination of Lincoln: “The authentic story of one of the greatest tragedies in our history.”

Although this text is part of the International Marketing Corp.’s sales pitch, it does hint at the ways that The Birth of a Nation was occasionally screened as a factual visualization of US history. For example, in February 1976, the film was shown at McMurry University in Abilene, Texas, as part of a film festival recounting the history of the country. The Birth of a Nation was the second film in the series, after 1776 (dir. Peter H. Hunt, 1972), and was used to depict the South’s view of the Civil War.[28]

Of the two shorts, only The Assassination of Lincoln was discovered in the research for this chapter; a copy exists in the Herb Graff collection at the Yale Film Study Center. It recounts the main points of the scene from the arrival of the president at Ford’s Theatre to Booth’s escape. Because the excerpt is just over three and a half minutes, it appears to be cut down from the original length of the scene. The other noticeable alterations are the opening and closing titles, the former reading “The Assassination of Lincoln” and the latter “The End.” For each, the font is generic and does not match the title card lifted from The Birth of a Nation or the other original intertitles found in the short. The added credits do not include other information such as the name of the distributor or a date of rerelease, suggesting these two excerpts were illicitly produced without the consent of the copyright holders: The Birth of a Nation’s producers, Roy and Harry Aitken.

As an example of how collectors would recirculate and transform the titles they collected, in 1947 David Bradley duped his personal copy of Civil War Battle Scenes, making six new copies for Theodore Huff’s filmmaking class at New York University for an assignment in which the students had to reedit a preexisting film.[29]

Even more illegitimate seeming were the 8 mm and 16 mm versions of The Birth of a Nation “with original sound score” that were advertised by an unknown source in the classified ads of Popular Photography in 1948 and in 1949 issues of Home Movies. The only identifying characteristic of the company selling these versions was a post office box in Philadelphia.[30]

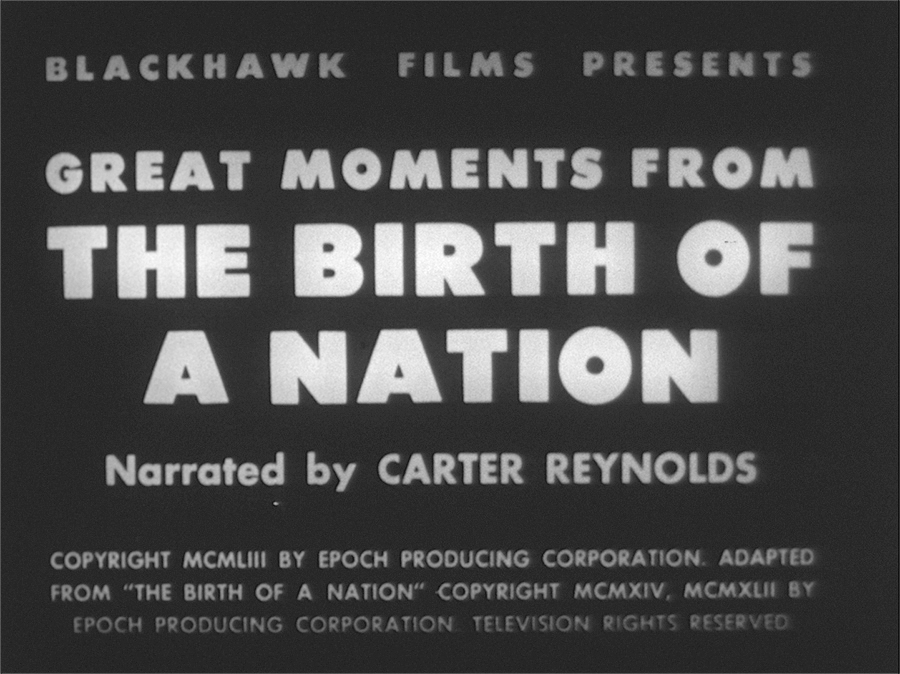

In 1953, Blackhawk Films released a nine-minute summary of the film with new narration called Great Moments from The Birth of a Nation. The short was released at a time when the home market was not large enough to support releasing full-length feature films. This cut-down version was a way for the then owners of the film, the Aitkens, to continue to financially profit from The Birth of a Nation.[31] Great Moments will be examined in detail in the next part of this chapter.

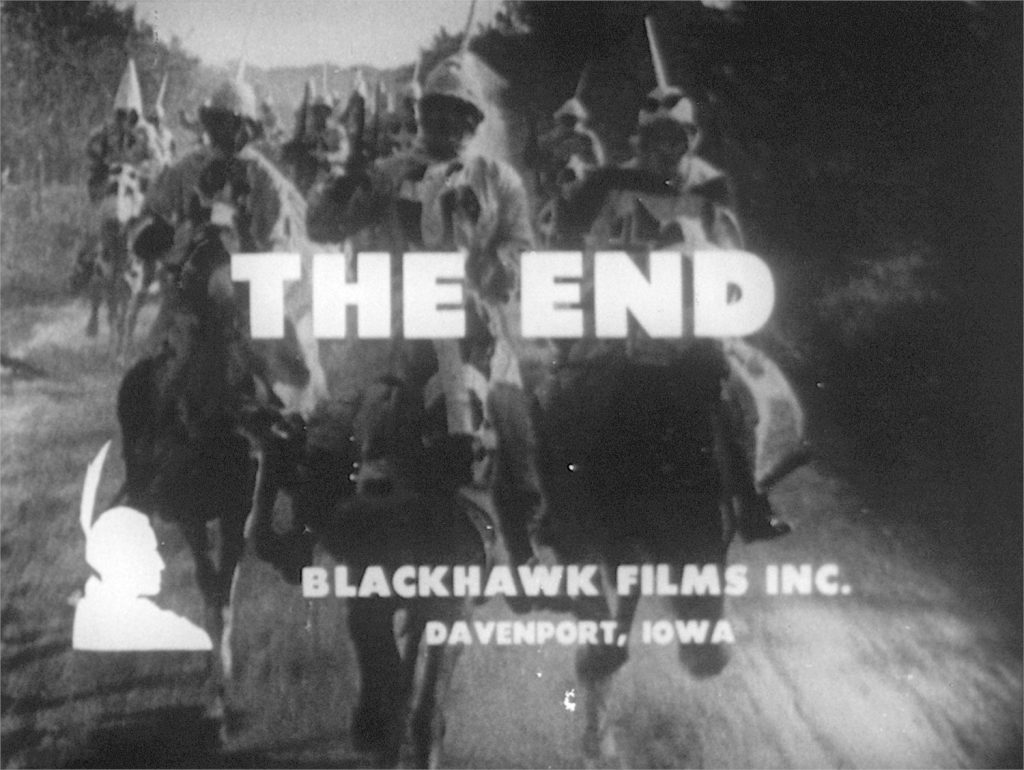

Showing the ways that collectors left their imprint on films in their collection, the reel of this short in the Bradley collection has an end credit added by the collector noting to whom it belongs, not unlike an ex libris stamp in a rare book (fig. 2.4).

The twelve-reel, black-and-white print that Bradley purchased in 1955 is harder to source. An article in the November 1954 issue of Home Movies on ways to add music to home screenings of silent films mentions a twelve-reel version that was “available with records of the original organ score.” Unfortunately, it does so without naming the company selling this version, but it does describe the print as one of the few silent films with added sound tracks that were then commercially available.[32]

That same year, Bradley attempted to buy a full-length print from the New Jersey company Movie Classics, but he was served notice from Harry Aitken, the copyright holder of the film at the time, that the sale was illegal.

Around the same time (the exact year is not known), actor and film collector John Griggs released a version on 16 mm to a select number of other collectors. His print of the film included a new score that Griggs produced of improvisations based on historical songs and played on organ, piano, and drums. An undated letter from Everson to the curator of the George Eastman House film collection, James Card, describes the film’s score in a sales pitch to the museum: “One of the best things about it is the spontaneous flavor. Before-hand, it was predetermined of course that the Clan [sic] call would be an oft-used motif, that ‘The Perfect Song’ would be used for Gish, and so on, but no definite cue-sheet was worked out. Johnny [Griggs] relayed instructions to Taubman [the organist Paul Taubman] via a microphone, and Taubman really seemed to get lost in the picture.”[33]

Griggs’s personal print of the film was included in the films that Yale University purchased from his estate in 1968, and which later became the genesis for the Yale Film Study Center.[34]

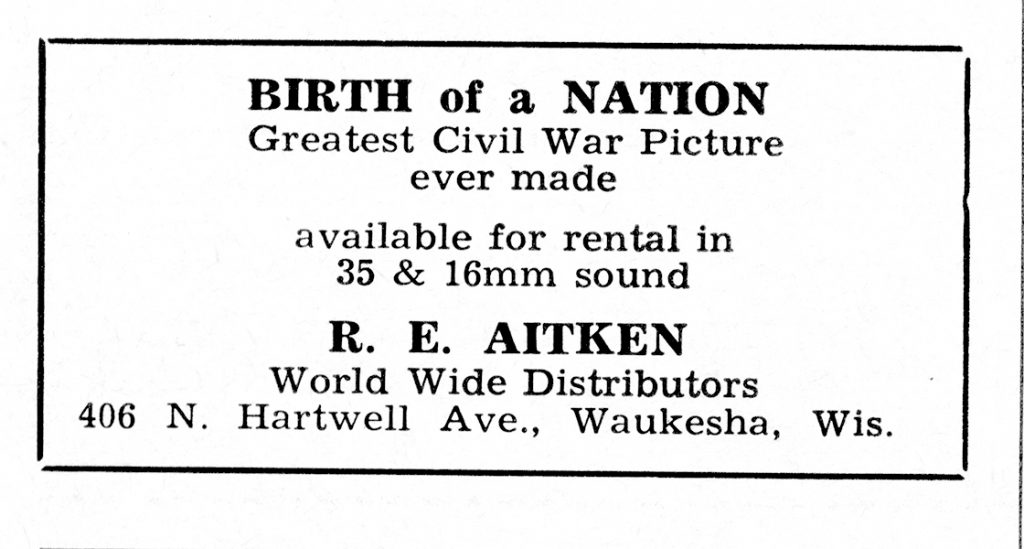

Roy E. Aitken, the film’s producer, continued to rent it out on 35 mm and 16 mm in a sound version that was likely based on the 1930 sound reissue. A 1962 ad on page 628 of the October issue of Educational Screen shows that he was marketing it to teachers for classroom screenings. No direct evidence of Aitken selling the print to the home market has been uncovered; however, Ingmar Bergman gained permission from the rights holder to acquire a copy of The Birth of a Nation for his personal collection (fig. 2.5).[35]

In 1965, Blackhawk was selling an 8 mm black-and-white print of the film, as mentioned in the New York Times article discussed earlier in this chapter.[36] Around the same time, Minot Films was selling a silent version of the 1930 sound reissue on 8 mm.[37]

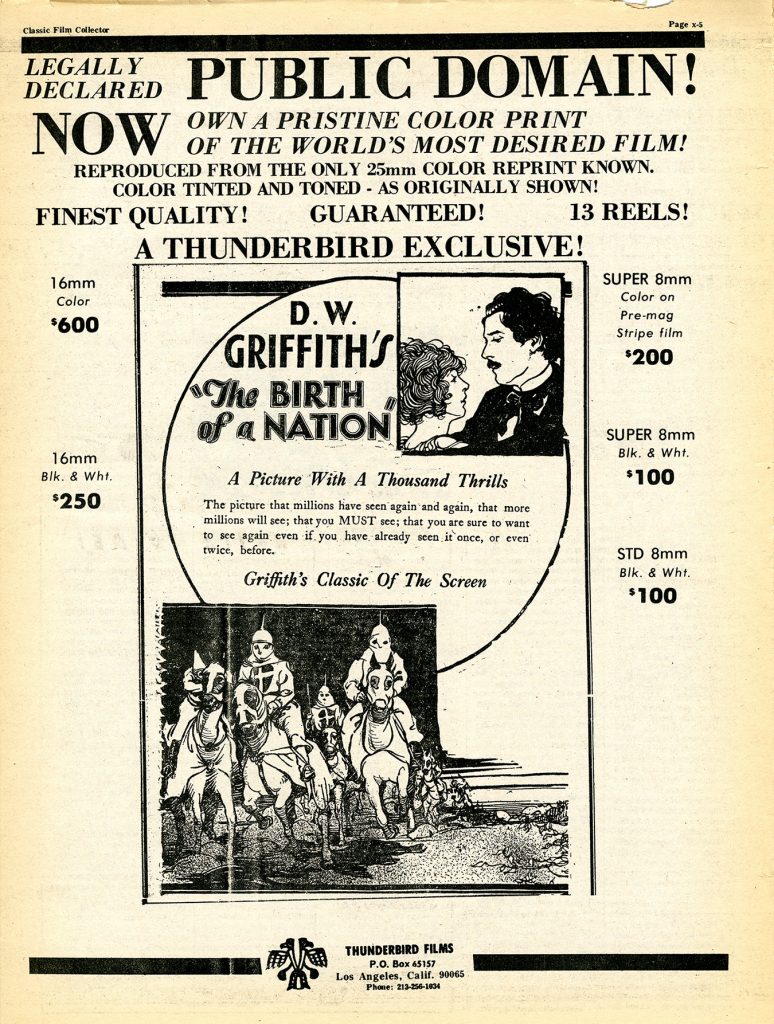

In August 1975, a ruling by the Second Circuit Court of Appeals on a lawsuit between film distributor Raymond Rohauer and television producer Paul Killiam over the disputed copyright status of The Birth of a Nation declared the film to be in the public domain.[38] The ruling unleashed film distributors that had previously withdrawn home versions or were wary of releasing copies of the film due to the risk of a lawsuit from Rohauer. By the fall of that year, Thunderbird Films was selling 16 mm and Super 8 mm versions of the film in color for $600 and $200, respectively (which, after inflation, would be about $2,600 and $880 in 2016). Thunderbird also released a black-and-white version in 16 mm, Super 8, and 8 mm at the same time (fig. 2.6).[39] The color print from Thunderbird was sourced from a 35 mm print originally released in 1921 that had been tinted and toned. That print had been owned by collector Lawrence Landry and was later used as the source for the restoration of The Birth of a Nation that was made in the early 1990s by David Brownlow and David Gill of Photoplay Productions.[40] The next year, Thunderbird added a new sound track created by the company’s owner, Tom Dunnahoo, to its 16 mm version of the film. The addition of the sound track increased the price by $100, making the cost of the color and sound version worth just under $3,000 in today’s dollars. Reinforcing the complex exhibition and reissue history of the film theatrically, and how those multiple “original” versions shaped and were altered by companies selling the film to the home and nontheatrical market, Thunderbird also offered a 16 mm version of the 1940 reissue, not the first 1930 sound reissue.[41]

By 1976, Griggs Moviedrome, now operated by Robert Lee of the Essex Film Club after Griggs’s death in 1967, was selling almost as wide an array of versions of The Birth of a Nation as Thunderbird. According to an ad on pages 46 and 47 of the summer 1976 issue of Classic Film Collector, the distributor was offering these products: 16 mm or Super 8 black-and-white silent prints; a 16 mm reduction print of the 1930 rerelease; The Prologue to The Birth of the Nation, an introduction by Griffith for the 1930 sound reissue; a trailer for the 1930 version with “a nondescript announcer reading inaccurate copy”; and a sound track of piano music on reel-to-reel or audiocassettes to accompany the silent version. Looking to differentiate their black-and-white version from the color copy available from Thunderbird, Griggs Moviedrome argued that its print was more authentic to the look of the initial theatrical experience of The Birth of a Nation. “There are no false color tones or tints added by printing on color stock, adding additional generations to the release prints [and thus degrading the photographic quality of the print], as we have kept it as close to the original as possible.”

In 1979, Blackhawk added a color version on Super 8, in silent and magnetic sound versions and running 158 minutes, to its existing line of black-and-white prints that it had been selling for a number of years.[42]

What Were the Great Moments from The Birth of a Nation According to Great Moments from The Birth of a Nation?

These multiple home and small gauge editions of The Birth of a Nation are an especially vibrant example of a business practice of Hollywood studios that Barbara Klinger describes as “recycling.”[43] Aftermarkets such as television broadcasts, viewing in hotels and in airplanes, and various evolving home media formats offer production companies a way to extend the profitability of a title past its original theatrical run. As the history of nontheatrical and small gauge versions of The Birth of a Nation illustrates, recycling can also be a way for nonproducers, fans, and alternative modes of distribution to reuse what copyright holders have neglected to monetize. As more companies and individuals become involved with the recirculation of a film, and as distributors send the film into specialized screening spaces for specialized audiences with different forms of exhibition technologies, it undergoes a material transformation: 35 mm prints are reduced to 16 mm or Super 8, full-length films are excerpted, sound tracks are added, and so on. As Klinger states, “the history of home exhibition has been at the same time a history of textual transfiguration.”[44] To better understand some of the alterations common to these nontheatrical circuits, this section presents a close analysis of the previously mentioned cut-down version titled Great Moments from The Birth of a Nation.

As previously stated, Blackhawk Films released Great Moments in 1953 under license from the copyright holders, Roy and Harry Aitken. Releasing a short version of The Birth of a Nation was a way to maximize the still-nascent market for commercially produced film prints. A shorter run time meant less film stock, which made the reel more affordable. Additionally, that it was not the complete feature lessened the chance of a home release cutting into any box office returns from a theatrical rerelease. This later became a fairly common practice for Hollywood studios in the 1960s and 1970s. Select titles would be edited down to anywhere from five to thirty minutes, most often with a condensed narrative, but sometimes focusing around a famous scene from a film. For example, in 1978 Universal 8, the small gauge division of Universal Studios, sold seventeen-minutes summaries of Psycho (dir. Alfred Hitchcock, 1960), Frenzy (dir. Alfred Hitchcock, 1972), and Airport (dir. George Seaton, 1970) while also offering a four-minute version of what were promoted as each films most spectacular scene, which was the shower scene, a rape and murder sequence, and a bomb explosion, respectively.[45]

However, Great Moments from The Birth of a Nation was neither a summary nor a selected scene from its parent film. Instead, the short was presented as a shared reminiscence of a decades-old but still important film both for the development of cinema and as a national event in its own right. The narrator led the audience through highlights of the film, recalling trivia about its production, the film’s stars, and its cultural and artistic impact. In doing so, the narrator engenders the remembering of certain elements from the film, such as its romance, historical sweep, and daring cinematic achievements. However, the choice over which scenes were left out—the attempted rape of Flora by Gus and his subsequent murder, and Lynch’s assault on Elsie—assists in the forgetting of some its most offensive racial stereotypes. As such, it acts almost as an updated defense of the film by its original producers. Despite its limited circulation primarily to collectors, Great Moments from The Birth of a Nation is an important piece of evidence in understanding the film’s reception, and the continued debate that surrounded it, in the early 1950s.

The didactic nature of the nine-minute short, and its intent to safeguard The Birth of a Nation’s place in history, begins at its very beginning. Common to releases by Blackhawk Films, Great Moments begins with a contextualizing introductory text that describes the importance of the film. For The Birth of a Nation these are split into two parts. The first is economic and covers the size of its budget, its unprecedented ticket price, and its unprecedented box-office success. The second is aesthetic offering praise for Griffith’s direction and Billy Bitzer’s cinematography.

The main body of the short is a selection of nine clips organized around the topic of the “many different reasons” audiences “who saw The Birth of a Nation back in the silent days” would still remember it in 1953. The first is a nostalgic appreciation of the film’s stars starting out with Lillian Gish and Henry Walthall. While the narrator’s text is limited to naming the two actors and their roles, the footage depicts the two in a romantic embrace; the short regularly relies on the visuals of the film to rehabilitate its reputation with only slight prompting from the narrator. Great Moments continues this section with a focus on two other actors: Mae Marsh as Flora, or Little Sister, and Wallace Reid as Jeff. For both, it is the fact they soon went to fame after their appearances in The Birth of the Nation that the narrator reminds viewers of, not anything to do about the plot of the film itself. In fact, it is during the segment on Reid that the disparity between the new narration and original footage becomes most apparent. While the voiceover mournfully recalls Reid’s “untimely and tragic passing in the early twenties” the clip from The Birth of a Nation show his character almost gleefully engaging in violence against the men in the saloon that are hiding Gus from the posse looking for vengeance.

The next segment of Great Moments moves from the film’s actors to the formal elements of the original. As the narrator states, “Many remember the film for its magnificent camera work. Such scenes as these were striking innovations for their time and had a profound effect on the photographic development of the motion picture.” The shot under discussion starts with a medium shot of a mother and children huddled together as the camera pans to the right reveal a battle scene in the distance, before panning back to the family.

In the following section, the theme of the film’s depiction of the Civil War becomes the focus. According to the narrator, “Many Hollywood directors, even today, feel that in the battle scenes Griffith achieved a realism and effectiveness that has never been excelled.”

The next two segments focus on The Birth of a Nation’s use of male melodrama through showing the Civil War’s effects on soldiers. One focuses on the impact an unknown extra supposedly had on the film’s original audiences. According to Great Moments, “One of the most famous scenes in The Birth of a Nation was this one at a makeshift military hospital in Washington where a moonstruck sentry cast a wistful glance at Lillian Gish. Thousands of letters were written asking for the name of this extra but he had vanished from the Hollywood scene.” The other follows the Little Colonel’s “return home only to find the once beautiful and gay Piedmont. His family almost reduced to a state of want.”

This is followed by two sections on the film’s ability to represent, faithfully according to its narrator, important moments from American history. These are the Confederacy’s surrender to Grant by Lee at the Appomattox Court House and Lincoln’s assassination at the Ford Theater. Besides signaling the historical veracity and accuracy of these scenes, Great Moments again focuses on the actors that went on to become well-known actors and directors, including Donald Crisp as Grant and Raoul Walsh as John Wilkes Booth.

The final two sections of Great Moments move to scenes from the second half of The Birth of a Nation. While explicitly acknowledging the controversy surrounding the original film, if only briefly, the short has the effect of amplifying the racist messages of Griffith’s feature. It addresses then quickly erases the debates over The Birth of a Nation. The penultimate segment of Great Moments covers the scene in the South Carolina statehouse with the voiceover, “Also to be remembered was the coming of the carpet baggers and with them a virtual state of anarchy in South Carolina and much of the South. The mulatto Lieutenant Governor of South Carolina, played by George Siegmann, led the carpet bagging legislature that created all sorts of indignities for the white minority.” As the shot fades on the black politician’s impropriety in the state capitol building, there is a cut to a rider calling the hidden Ku Klux Klan out of the woods. Visually the short film ends with the ride of the Klan. The dialogue spoken over the Klan members riding furiously on horseback is worth quoting in full for the way it conflates film history and national history, and southern White racism with national patriotism (fig. 2.7).

And here in the birth of the Ku Klux Klan, the South waged a new revolution and The Birth of a Nation got its most spectacular and its most controversial ingredients. This great film was adapted from The Clansmen by Thomas Dixon. At a special showing on the night of February 20th, 1915, as the final scene faded out, Dixon shouted to Griffith, “The Clansmen is too tame a title. Let’s call it The Birth of a Nation!” And as The Birth of a Nation it opened at the Liberty Theater in New York on March 6, 1915. The Birth of a Nation, on the way to becoming the most famous motion picture of all time.

Collectors’ Views on The Birth of a Nation

Great Moments relied on a nostalgic appeal to sell a significantly shortened version of Griffith’s film to the limited home market that existed at the time. The narrator’s use of the second person plural to address the audience—“Those of you . . . ” and “Some of you . . . ”—allows for a reconstruction of the type of viewer Blackhawk and the Aitkens imagined might be watching the short. Based on the “great moments” the shorts replays and comments on for its audience, the viewer was envisioned as a white person old enough to have seen The Birth of a Nation in the silent era and who, almost forty years later, wanted to relive the excitement and spectacle of Griffith’s film as a foundational work of cinematic art and a mass media sensation. It is easy to imagine, looking back at this short film from 2016, that some reactionary viewers might have seen Great Moments as fulfilling a revanchist dream, where the riding of a previous version of the Klan acted as a model for groups fighting to maintain a repressive culture of Jim Crow laws against the burgeoning civil rights movement.

But did this imagined viewer of Great Moments match the collectors who owned the short, or other nontheatrical versions of The Birth of a Nation? In some ways, yes. Most film collectors at the time were male, white, adult, and were film buffs interested in studying and rewatching the development of the cinematic art form. But what about agreeing with the argument presented in Great Moments? Can we assume it represents collectors’ opinions on the film as an artistic achievement, cultural force, and purveyor of antiblack sentiments? Could they have, perhaps, purchased the short film as it was the only, legally, available version of the feature for the home market at the time? Could they have disagreed with the short’s message, even while appreciating, if in a complicated manner, Griffith’s film? To widen this series of questions out, does ownership of a cultural product imply a shared worldview? Or does collecting act to suture the ideologies of the collector and the producer? To align this inquiry with the questions animating the larger reevaluation of The Birth of a Nation at its centenary and beyond, why the continued preserving, restoring, exhibiting, repackaging, and purchasing of a film that worked to cement racist stereotypes into the core visual language of cinema?

Based on the massive popularity of the film during its initial release and subsequent rereleases and its status as the origin point for feature filmmaking in America, it is no surprise that collectors often expressed strong praise for the film. For example, in 1972, a collector refused to sell his copy of the film even though it had reached a higher monetary value due to being removed from the market because of the copyright struggles over the film that lasted from 1965 to 1975. “He considers the epic probably the greatest movie ever filmed despite the controversy over its scenes depicting slavery and the Ku Klux Klan.”[46] That same year, another film collector called it “his favorite film of those he owns.” This second collector justified his appreciation of the film based on its long-term box office success, the recent Academy Award presented to Lillian Gish, and the accolades from scholars and film critics.[47]

Other collectors were more critical of the film. The television screenwriter Samuel Peebles wrote a monthly column on film collecting for the journal Films in Review from 1965 until 1977. He regularly offered advice to collectors on how to find film prints, how to avoid violating copyright laws, and the best way to screen old films for one’s friends and family. In a November 1976 column, Peebles laid out his theory on what constitutes “an ideal or representative film collection.” He argues, “If you seriously collect old movies, there are many you should have not only for study but to screen for others interested in the history of films” (emphasis in the original). This suggests a dispassionate, rational, and studious approach to collecting films. Under Peebles’s selection process, one would collect films based on their reputation and cultural significance. To understand cinema, one would have certain types of important films regardless of individual opinions. Film history happened, and a refined collection reflects the important milestones, advances, and filmmakers of cinema.

However, collecting according to this model does allow for a degree of individual choice when choosing a title that acts as a synecdoche for a larger filmmaking era, style, or oeuvre. As Peebles states, “If possible, choose one title to represent a particular thing: e.g., if I were limited to one film by D. W. Griffith, I’d choose Intolerance. It holds much of his greatness, and though not a financial success, it is a recognized classic; less controversial, even today, than The Birth of a Nation.”[48] A serious film collector needs a Griffith, but it does not need to be The Birth of a Nation. Peebles does not expand on the controversial nature of The Birth of a Nation or his discomfort with the film. Yet he implies that building a film collection is a personalized act of canonization that is a negotiation between common assumptions about film history—“greatness” and “classic”—and present-day politics and taste. An ideal film collection must acknowledge the past but is not entirely bound by it; collections are built to address current standards and to screen for current audiences. The repression of African Americans and promotion of the Ku Klux Klan in The Birth of a Nation, in Peebles’s view, removed it from automatic inclusion into his collection.

Collector and repertory theater owner John Hampton took an alternative approach to The Birth of a Nation. As the co-owner and programmer of the Silent Movie Theatre in Los Angeles from 1942 to 1979, Hampton played an important part in keeping silent films in the public view before the rise of videotape. Hampton supplied the films, which played for weeklong runs, from his extensive film collection, projected the films himself, and supplied the musical accompaniment from his collection of 78 rpm phonographs. The Silent Movie Theatre housed repertory screenings put on by Cinefamily until its closure in 2017, and Hampton’s collection of rare films, which includes a number of unique prints of otherwise lost silent features, is owned by the Packard Humanities Institute, one of the major backers of film preservation in the United States.

Hampton regularly screened his personal print of The Birth of a Nation at his theater to large audiences. It is the first title in a listing of “the theater’s staple presentations” in a short 1980 update on the Silent Movie Theatre in the Los Angeles Times. (The other staples included Intolerance [dir. Griffith, 1916], King of Kings [dir. Cecil B. De Mille, 1927], the Clara Bow vehicle The Plastic Age [dir. Wesley Ruggles, 1925], and Sparrows [dir. William Beaudine, 1926].)[49] It was also described as one of the theater’s “consistent hits” in 1977.[50] The film played for a week run starting on Wednesday, June 28, 1967, preceded by a “Laurel and Hardy patriotic short.”[51] The Birth of a Nation is included in a 1966 article in Hampton’s response to a reporter’s question about the theater’s “biggest favorites—box office wise?” The collector answers, “Those that were popular in the old days seem to remain popular.”[52] Griffith’s film takes the lead in a description of “Mr. Hampton’s choicest items” in an article from 1960.[53] In another article from the same year, Hampton recalls the popularity of The Birth of a Nation in 1948, the first time he publicly screened it. “‘Why people lined up clear to Melrose Ave. [more than 500 feet away] to see the first show,’ he says.”[54] An article appearing in the New York Times in October 1948 describes that run as “drawing vast audiences” and doing “turnaway business.” Indicating, though not explicitly naming, the protests that regularly accompanied public screenings of The Birth of a Nation, according to the journalist, “no untoward incidents marred the week’s run.”[55]

That same 1948 article from the New York Times provides insight into Hampton’s view on the film and his justification for screening it on what became a yearly basis. His mission for the theater was to create a shrine for silent cinema, but in a way that countered the more serious-minded, high-art approach to screening silent films developed by the Museum of Modern Art and other film societies.[56] Hampton was “much more interested in re-creating a program of film entertainment as it was enjoyed some twenty-five or thirty years ago, complete with a two-reel comedy, a serial, a cartoon and a feature picture.”[57] However, recreating the exhibition strategies of the past did not automatically equal reconstructing the ideological and racist inflections of the films themselves. If Hampton’s project was built on a nostalgia for filmmaking before the arrival of sound, he argued that it was possible to separate the cinematic style from the message when rescreening old films. As a supporter of the Committee on Racial Equality, Hampton stated that, while he disagreed with the virulently racist stereotypes in The Birth of a Nation, “silent films which used such types should be viewed with intelligent understanding of their place in film history.” Further, he believed his audience, as silent film aficionados, was sophisticated enough to appreciate Griffith’s artistry while categorically rejecting the director’s worldview. However, Hampton expressed uncertainty whether general audiences would be able to do the same, implicitly pointing out the differences between private or semipublic screenings and the manner in which a mass audience, less educated about film history, might be more susceptible to its propagandistic appeals.[58]

This ability to bifurcate a film’s artistry and ideology was central to collector and historian William K. Everson’s explanation for screening The Birth of a Nation. As a prolific author of books and articles about silent cinema, Westerns, and B pictures; a collector who regularly interacted with leading film archives; a professor at New York University and the School of Visual Art; and programmer with the New York–based Theodore Huff Memorial Film Society, Everson grappled with the place of The Birth of a Nation in film history and the value and purpose of showing it decades after its release. His unpublished notes based on the lectures he gave on the film around 1972 condense his arguments for doing so. Interestingly, these notes themselves reflect the split between cinema as form and as message that he argues for, because Everson wrote notes only on the section of his lecture on this justification for screening and studying the film and not on the opening part of his lecture about its “technical and artistic aspects.”[59]

Everson based his argument around four major points. First, while conceding that The Birth of a Nation appeared racist to viewers in 1972, Everson contended it was more representative of a generalized “condescension” that Griffith, as a Southern white man inculcated in what were the norms of white supremacy at the time, felt toward African Americans across his films rather than the outright “race-hatred” expressed by Dixon in The Clansman and The Leopard Spots.[60] For the former, Everson points to the faithful servant motif regularly employed by Griffith as proof of the director’s patronizing view of African Americans; for the latter, Everson argues that Griffith largely replaced Dixon’s “bigoted diatribes which seem to exist only to dispense racial hatred” with moments of cinematic spectacle and grandeur.[61]

Second, Everson argued that Hollywood had made “many, many films from all periods (and dealing with races other than blacks) that have been FAR more racist than The Birth of a Nation” (emphasis in the original). According to Everson, movies such as Square Shooter (dir. David Selman, 1935), Golden Dawn (dir. Ray Enright, 1929), and The Mask of Fu Manchu (dir. Charles Brabin, 1932) had not received the same degree of opprobrium as Griffith’s film because they were not reissued and screened as regularly and were not as integral to the common assumptions about the development of the medium.[62] While this line of defense may not be convincing—arguing the other films are more harmful does not necessarily vindicate Griffith’s representation of black America—it does, perhaps unintentionally on Everson’s part, raise the larger issue of what it means to be a fan, cinephile, or collector of an art form like Hollywood cinema, which so regularly relied on racial stereotypes. I raise this point not to accuse this specialized film culture of collectors, but to suggest the ways that studying the nontheatrical reception and private ownership of The Birth of a Nation opens up a discussion of the politics of collecting, and also of film archiving and film history.

Everson’s third justification for screening and studying The Birth of a Nation revolved around the power of Griffith’s filmmaking over its original audiences, who were unaccustomed to cinema’s visual storytelling. Everson states: “The impact of the film at the time was incredible, since it brought a whole new language with it; it was as though audiences that had known literature only through comic books were suddenly introduced to the works of Tolstoy and Dickens. Audiences were swept away by the dynamism of the film, and didn’t understand that film can be cut so that shot A plus shot B can lead to a shot C that may have a totally different meaning.”[63] Although this argument relies on an assertion that historical viewers were naive and that current spectators are more cultivated, a move based perhaps more on assumption than historical evidence, Everson’s point seems to be that the film would have been less controversial if the original audiences had been more media literate. If they had not succumbed to Griffith’s visual power, if they had been able to understand the intent behind cinematic signifiers such as a pan, iris, or cut, they would have been able to discount the director’s social message and historical revisionism while appreciating his artistic skill.

Despite describing present-day viewers as sophisticated readers of cinematic technique, Everson still proposed that the film should be screened only when properly contextualized. This is his fourth justification for exhibiting it: that it be presented in controlled settings. Everson disapproved of The Birth of a Nation being “shown today for racial purposes, or even commercially where [its] influence would be widespread.” Instead, it, and other offensive films need to be “studied dispassionately as records of racist attitudes of another day.” This is possible by adopting an “aloof” model of spectatorship, where a viewer, informed by the historical circumstances of a film’s production and reception, can, almost paradoxically, sidestep the cultural, political, and racial messages of a film to examine its artistic intent.[64] This act of knowing and then placing aside allows a viewer, in Everson’s postulation, to escape the emotional influence of a film. According to Everson, film studies provides a defense for the viewer and defangs a film of its ideological power by helping students understand how a filmmaker might employ cinematic techniques and style to communicate, persuade, and propagandize.

Conclusion: What’s So Important about the Development of Film Art?

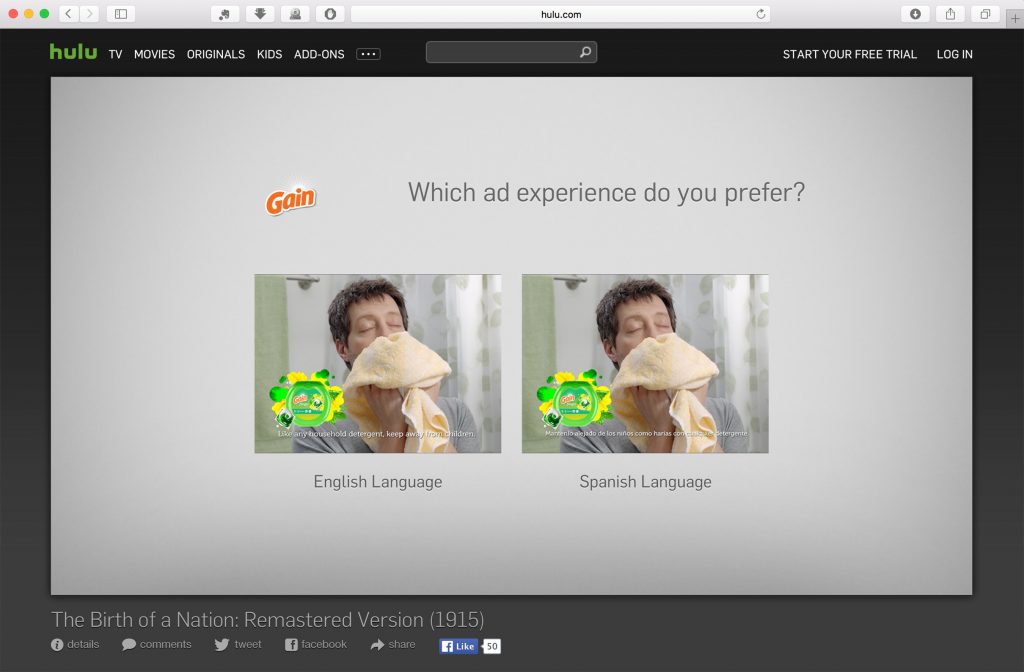

After almost forty years of home video on VHS, DVD, Blu-ray, and online streaming, the idea of films in the home is no longer news. The Birth of a Nation today is easier to see, in better-quality and more faithful versions, than at any time since its original release in 1915. After being released on VHS as early as 1980, The Birth of a Nation is currently available on DVD from multiple distributors, including Kino, VCI Entertainment, two versions by Reel Classic DVD, Image Entertainment, and many budget companies dealing with films in the public domain. It is currently on Blu-ray in different restored versions from three companies: Kino, Eureka, and the British Film Institute’s home media imprint. Additionally, as of February 2016, the film can be found uploaded on YouTube by more than twenty different users, though the quality and provenance of many of these is questionable at best. And The Birth of a Nation can be streamed on Hulu, in a restored version from Kino. The streaming platform monetizes viewing by selling ads before the film, which when reviewed in researching this chapter was, through the random serendipity of the algorithms controlling online advertisements, a 2015 ad for Gain detergent (fig. 2.8).

Equally common is the idea that the film’s artistry can be understood, and even appreciated, in spite of its role in defining and amplifying black stereotypes on film. In a recent online article describing the restoration of The Birth of a Nation on Blu-ray, a conservator involved in a recent home media release of the film argues that a century of debates over the nature of the film and the impact of its racist messaging should not stop modern-day audiences “from acknowledging the part it played in the development of the American film industry, or, crucially, the rise of cinema as art.” Moreover, “the only way to fully appreciate what it was that so electrified audiences in 1915 is to actually see the film—and to see it properly presented. Yet since the advent of sound there have been few opportunities to see Birth as its maker originally intended.”[65] The author is implicitly critiquing the silent, reedited, black-and-white, and poor-quality versions that circulated on small gauge film prints in the mid- and late twentieth century, and which this article has attempted to place with the larger distribution and reception history of The Birth of a Nation. Without a doubt, this current restoration is a feat of archival, editorial, artistic, and technical skill, expertly building off an earlier restoration in the early 1990s as well as reflecting in-depth research on the original nitrate prints and negatives held at the Library of Congress.

However, the question I would like to close on is this: When a collector saves a rare print, or an archivist preserves a film, or a film programmer screens a title from the past, and the intent is to create an experience something like that which a historical audience would have experienced, which audience from the past are we talking about, and who might we be ignoring? If The Birth of a Nation electrified some audience members in 1915, it clearly shocked others. Can a film be restored and exhibited to recreate both responses?

Andy Uhrich is a PhD candidate in Communication and Culture at Indiana University and film archivist at the Indiana University Libraries Moving Images Archive.

- Jacob Deschin, “Classics on Home Screen,” New York Times, February 14, 1965, X23. ↵

- See Melvyn Stokes, D. W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation: A History of “the Most Controversial Motion Picture of All Time” (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007); J. B. Kaufman, “The Birth of a Nation: Non-Archival Sources,” in The Griffith Project, ed. Paolo Church Usai, vol. 8, Films Produced in 1914–1915 (London: British Film Institute), 107–112; and John Cuniberti, The Birth of a Nation: A Formal Shot-by-Shot Analysis Together with Microfiche (Woodbridge, CT: Research Productions, 1979). ↵

- For more on earlier efforts to market cinema to the home, see Ben Singer, “Early Home Cinema and the Edison Home Projecting Kinetoscope,” Film History 2 (1988): 37–69; Moya Luckett, “‘Filming the Family’: Home Movie Systems and the Domestication of Spectatorship,” Velvet Light Trap 36 (1995): 21–32; and Haidee Wasson, “Electric Homes! Automatic Movies! Efficient Entertainment! Domesticity and the 16 mm Projector in the 1920s,” Cinema Journal 48, no. 4 (Fall 2009): 1–21. ↵

- Deschin, “Classics on Home Screen.” ↵

- For an in-depth discussion of the construction of the figure of the serious amateur filmmaker, see Charles Tepperman, Amateur Cinema: The Rise of North American Moviemaking, 1923–1960 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2014). ↵

- Greg Waller, “Free Talking Picture—Every Farmer Is Welcome: Non-theatrical Film and Everyday Life in Rural America During the 1930s,” in Going to the Movies: Hollywood and the Social Experience of Cinema, ed. Richard Maltby, Melvyn Stokes, and Robert C. Allen (Exeter, UK: University of Exeter Press, 2007), 266. ↵

- Leah M. Kerr, “Collectors’ Contributions to Archiving Early Black Film,” Black Camera 5, no. 1 (2013): 274–284; Jacqueline Stewart, “Discovering Black Film History: Tracing the Tyler, Texas Black Film Collection,” Film History 23, no. 2 (2011): 147–173. ↵

- Deschin, “Classics on Home Screen.” ↵

- William K. Everson, Announcing a New Film Society at the School of Visual Arts, 1967, Series I: Correspondence, Subseries A: Alphabetical, William K. Everson Collection, George Amberg Memorial Film Study Center, New York University. ↵

- William K. Everson quoted in Bruce Goldstein, “Adventures of the Huff Society,” Film Comment 33, no. 1 (January/February 1997): 71. ↵

- “Film Events: ‘Citizen Kane’ to Be Shown,” San Mateo Times, July 14, 1971, 38. ↵

- “Hill Theatre Group Offers Diverse Summer Programming,” Potrero View, July 1, 1971, 3. ↵

- Garry Wills, “American Past of Racial Violence Should Be Aired,” Indianapolis News, December 25, 1970, 13. ↵

- Tom Rice, White Robes, Silver Screens: Movies and the Making of the Ku Klux Klan (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2015), 3. ↵

- Some of these screenings are mentioned by Janet Staiger, Melvyn Stokes, and Frank Beaver in Janet Staiger, Interpreting Films: Studies in the Historical Reception of American Cinema (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1992), 139 and 152–153; Melvyn Stokes, American History through Hollywood Film: From the Revolution to the 1960s (New York: Bloomsbury, 2013), 259n37; and Frank Beaver, “A Film That Won’t Go Away,” Michigan Today, February 15, 2015, http://michigantoday.umich.edu/a-film-that-wont-go-away/. ↵

- Rick Martinez and Jan Cleveland, “KKK Alive and Well in the Inland Empire,” San Bernardino County Sun, June 25, 1978, 1 and 3. ↵

- “Klan Holds Service Near Davis’ Birthplace,” Kokomo Tribune, June 5, 1978, 13. ↵

- “300 Protestors Battle Police as Klan Sees ‘Racist’ Film,” Des Moines Register, July 31, 1978, 1. ↵

- “National and International News in Brief,” Philadelphia Inquirer, July 9, 1979, 3; Eric Hodge, Rebecca Martinez, and Phoebe Judge, “Criminal: Birth of a Massacre,” WUNC 91.5, May 20, 2016, http://wunc.org/post/criminal-birth-massacre#stream/0. ↵

- Information on the failed 1954 sale is from David Bradley to William Donnachie, February 2, 1954, Series III: Correspondence, Box 94, William Donnachie: 1951–1966 folder, Bradley mss., 1902–1997, Lilly Library, Indiana University. The rest is from Series XIV: Miscellaneous, Box 126: Distribution records, index cards, A–G, of the same collection. ↵

- Dorothy E. Cook and Eva Cotter Rahbek-Smith, Educational Film Catalog (New York: H. W. Wilson, 1937), 122. ↵

- “Birth of a Nation in Court Again,” Afro-American, July 27, 1940, 13. ↵

- Dino Everette, February 10, 2010 (10:41 p.m.), comment on “What’s missing from my ‘Birth of a Nation’ print?” 8mm Forum, February 8, 2013, http://8mmforum.film-tech.com/cgi-bin/ubb/ultimatebb.cgi?ubb=get_topic;f=1;t=007902#000000. ↵

- “Film Group Announces New Program Series: Museum Library Compiles Film Series Four for National Showing,” Washington Post, July 16, 1937, 13. ↵

- “Contacting the Circulating Film and Video Library,” MoMA, 2016, https://www.moma.org/momaorg/shared/pdfs/docs/learn/pricelist_2018.pdf. ↵

- Stone Film Library, Advertisement in Educational Screen, February 1938, 60. See pages 246 and 259 of Stokes, D. W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation, for a discussion of how the Stone version was protested by the NAACP in New York State and was the source of a lawsuit from Thomas Dixon against the Stone Film Library. ↵

- International Marketing Corp., Advertisement in Home Movies, June 1942, 242. ↵

- “McMurry Film Festival Selections Trace Growth, Changes of Country,” Abilene Reporter-News, February 8, 1976, 24. Based on the description of the print to be screened, it is likely the festival projected the Thunderbird print that was released in the fall of 1975. ↵

- Theodore Huff to David Bradley, September 18, 1947, Series III. Correspondence, Box 95, Theodore Huff, 1947–1953 folder, Bradley mss., 1902–1997, Lilly Library, Indiana University. ↵

- Unknown company, Classified advertisement in Popular Photography, October 1948, 257; Unknown company, Classified advertisement in Home Movies, February 1949, 108. ↵

- Telephone interview with David Shepard, November 11, 2015. ↵

- “Old Time Movies with Sound,” Home Movies, November 1954, 418 and 436. ↵

- William K. Everson to James Card, May 25, no year, Series I: Correspondence, Subseries A: Alphabetical, James Card folder, William K. Everson Collection, George Amberg Memorial Film Study Center, New York University. ↵

- “Actor John Griggs’ 207 Vintage Print Nucleus of Yale Collection,” Variety, April 10, 1968, 24. ↵

- Geoffrey Macnab, Ingmar Bergman: The Life and Films of the Last Great European Director (New York: I. B. Tauris, 2009), 116. ↵

- For a look at the other films Blackhawk was selling in addition to The Birth of a Nation at the time, see Blackhawk Films, Advertisement in 8mm Collector, Spring 1966, 28. ↵

- James E. Ennis, “The 8 mm Feature Part 2: An Annotated Listing of 8 mm Silent Feature Films,” Classic Film Collector (Winter 1973): 20. ↵

- For more on this lawsuit and the convoluted rights of the film, see Anthony Slide, American Racist: The Life and Films of Thomas Dixon (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2004), 203–208; Stokes, D. W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation, 262; and Bosley Crowther, “An Accounting Is Sought on The Birth of a Nation," New York Times, January 4, 1965, 35. ↵

- Thunderbird Films, Advertisement in Classic Film Collector, Fall 1975, x–5. ↵

- David Gill, “The Birth of a Nation: Orphan or Pariah?” Griffithiana 20, no. 60/61 (October 1997): 17, 19. ↵

- Thunderbird Films, Advertisement in Film Collectors World, September 1976, 26; Scott Vernon, “Pirates of the Film Kingdom,” Los Angeles Times, April 23, 1976, E22. ↵

- Blackhawk Film Digest: May 1979 Catalog, May 1979, 48. ↵

- Barbara Klinger, “Cinema’s Shadow: Reconsidering Non-theatrical Exhibition,” in Going to the Movies: Hollywood and the Social Experience of Cinema, ed. Richard Maltby, Melvyn Stokes, and Robert C. Allen (Exeter, UK: University of Exeter Press, 2007), 276. ↵

- Klinger, “Cinema’s Shadow,” 281. ↵

- Universal 8, 1978 Super 8mm and 16mm Sound and 16mm Sound and Silent Catalogue, Universal City Studios, 1977, 3, 9–10. ↵

- Myra Setliff, “Lubbock Man’s Collection of Old Films Outstrips Those on Late, Late Shows,” Lubbock Avalanche-Journal, January 11, 1972, 5. ↵

- George Markell, “‘Rog’ Gonda to Show Oldtime Films: Silent Movie Era Returning,” Salem News, October 28, 1971, 10. ↵

- Samuel A. Peebles, “Films on 8 and 16,” Films in Review, November 1976, 560. ↵

- “Silent Movie,” Los Angeles Times, December 30, 1980, H9. ↵

- Philip K. Scheuer, “Silent Films Only: Horse and Buggy Movie House,” Los Angeles Times, February 22, 1977, F1. ↵

- “Movies: Opening,” Los Angeles Times, June 25, 1967, 5. The Laurel and Hardy short might have been The Tree in the Test Tube, which was produced in 1942 by the U.S. Department of Agriculture to promote the war effort. The film can be viewed on the National Archives YouTube channel at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vyY4W-ETC_Y. ↵

- Philip K. Scheuer, “All Is Not Quiet on the Silent Movie Theater Front,” Los Angeles Times, April 10, 1966, B3. ↵

- Gladwin Hill, “Silent-Film Buff Shows His Wares: John Hampton of Hollywood Discusses Collection and Theatre He Operates,” New York Times, November 21, 1960, 33. ↵

- “Museum of Films: Silent Films Glorified at Old-Time Theater,” Los Angeles Times, November 28, 1960, 10. ↵

- Elihu Winer, “A Reminder of the Past in Present Day Hollywood,” New York Times, October 24, 1978, X5. ↵

- For more information on the Museum of Modern Art’s attempts to rehabilitate popular silent cinema as a high culture art form, see Haidee Wasson, Museum Movies: The Museum of Modern Art and the Birth of Art Cinema (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005). ↵

- Winer, “A Reminder of the Past.” ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- William K. Everson, The Birth of a Nation: Some Random Thoughts on Its Impact and Its Racial Attitudes, 1972, Series VIII: Unpublished Manuscripts, Subseries A: By William K. Everson, William K. Everson Collection, George Amberg Memorial Film Study Center, New York University, 1. ↵

- Ibid., 2. ↵

- Ibid. Melvyn Stokes expands on and critiques this line of defense of the film by Everson and other critics, including Richard Schickel, on pages 282 and 283 of D. W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation. ↵

- Everson, The Birth of a Nation: Some Random Thoughts, 4. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid., 5. ↵

- Patrick Stanbury, “The Birth of a Nation: Controversial Classic Gets a Definitive New Restoration,” Brenton Film, February 17, 2016, http://www.brentonfilm.com/articles/the-birth-of-a-nation-controversial-classic-gets-a-definitive-new-restoration. ↵